FEATURES:

- Over three hundred locations across North America

- Mentioned in a Drake song

- Has lots of murals, possibly painted by a single artist

The restaurant looms over the mall parking lot, a hodgepodge of Ottoman arches, onion dome towers, and curved gold spires. It’s a perfect sunny evening, the best we’ve had in weeks, but the outdoor seating area is desolate; everyone’s inside. Our eyes take a minute to adjust to the darkness as the hostess leads us to our booth. We take off our masks, like everyone else, and, like everyone else, we’re stoked to be here.

I’m here because I heard an unusual story, from a friend of a friend (he is a server at the restaurant), about the man who paints the murals in every Cheesecake Factory by hand. One man, every single mural, at all 308 locations in the US and Canada. It’s a piece of company lore, my friend of a friend told me, a story passed down to him by his manager. After hearing this story, I wanted to see the murals. So on a recent August evening, I convinced three friends to drive out with me to the Twin Cities suburb of Edina, Minnesota, to see them for ourselves.

The Cheesecake Factory has been in business since the ’70s, but in the past decade it’s become something of a meme. When Drake sings, “Why you gotta fight with me at Cheesecake? You know I love to go there,” the restaurant is an object of perfect absurdity in a lyric written to go viral. A year after the Drake song came out, a popular Twitter thread described the restaurant as a “postmodern design hellscape.” The company gets online attention for the smallest details of its corporate structure, like its nearly five-hundred-page operations manual (a full page on how to properly handle strawberries!) and its decision not to pay rent at the start of the pandemic (“Who had money on Cheesecake Factory starting the revolution?” one person tweeted). With all this attention, it’s gained a spot on the list of things we consider to be illustrative of late capitalism, like gas station television, “Instagram Face,” Hudson Yards, hologram Tupac, branded shitposts, and The Masked Singer,to name a few—the dystopian products of a declining culture. They are chaotic objects, cynical and alienating, but (therefore?) we consume them anyway.

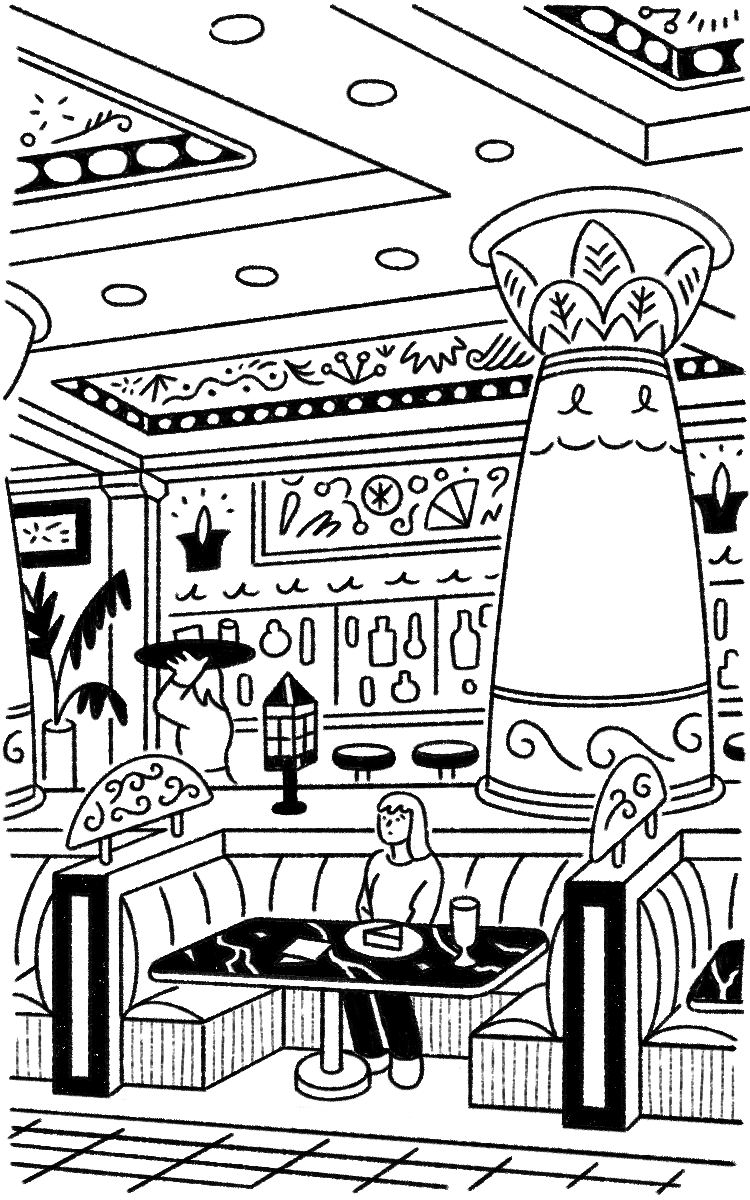

Looking around the restaurant, I can see why. It is a strange and funny place, easy to make fun of but hard to hate. I suppose I had been picturing the strip-mall restaurants of my youth, TGI Fridays or Red Lobster, but the vibes here are glitzier, more sanctified. The place is packed, and the mood is “date night.” The lamps burn low and yellow. Overhead, Shawn Mendes and Camila Cabello sing, “I love it when you call me señorita…”It would be hard to imagine somewhere that’s less like a factory. The Cheesecake Factory is all warm tones and soft, curving edges. It’s both ancient and plastic, suburban and foreign, tacky and genuinely fancy. Most of all, it’s fun.

Saturating the place, on every wall and in every alcove, are the murals. There they are, overhead, in the cupola ringed with lights above our booth. Bright pastel waves; circling chiral birds. Women. Decorative shapes around the columns, chains of ornamental flowers in blue and orange. The murals are psychedelic and vaguely Easter-ish, and in a normal place they would stand out, but here they are nearly lost in the bricolage of crumbling sphinxes, Grecian columns, wallpaper that looks like cracked marble, and glowing orange sculptures that resemble cats’ pupils or the Eye of Sauron. Still, there is something affecting about the murals, seeing each brushstroke on the wall and picturing the hand that made it.

Before my visit, I had wanted to talk to the creator of these murals. It seemed to me that the sole artisanal painter for a vast corporate empire might have something profound to say about late capitalism and our perverse obsession with it. I tracked down the alleged artist’s personal website, where he writes: “In essence, we are living deeply immersed in a multidimensional reality where everything in our existence is fundamentally composed of vibrating energy that is in a constant state of flux, and nothing in our reality is, in fact, ‘solid.’”This seemed promising. I emailed him and messaged him on Facebook and Instagram, with no luck. (His Instagram offered little insight; the few photos and process videos of his murals were drowned out by anti-vaxxer memes and woo-woo appeals to higher consciousness.) At the restaurant, as I look up at the swirling shapes, the art produces no great revelation, either. It does not speak for itself—or maybe that’s all it does. Mostly, I wonder if he likes what he paints here or if he does it just for money.

Today, the company is worth over two billion dollars. Whereas similar restaurants like Applebee’s and Olive Garden have struggled, the Cheesecake Factory is known for being the rare suburban chain to continue expanding. During the pandemic, the restaurant pivoted to online delivery and thrived, despite temporarily furloughing forty-one thousand workers in March 2020. In 2021, employees spoke out about the increasingly frantic work pace, as they had to meet the demands of hundreds of delivery orders in addition to those of a restaurant once again packed with customers.

Speaking of which, we’d better order. We’ve been giddily reciting the menu items for the sheer pleasure of it: Buffalo Blasts! Steak Diane! Coconut Cream Pie Cheesecake! We’re nearly shouting. The menu is huge, over twenty pages divided into Byzantine sections. To start, we order the Fried Macaroni and Cheese, which comes with a tart tomato-cream sauce, and the Avocado Eggrolls, which are delicious and unlike anything I’ve ever eaten (so much piping-hot avocado), paired with a kind of syrupy pesto. Eating it, I think: This is the apotheosis of fusion cuisine. The food keeps coming, we keep scarfing it down, and it feels like the mural painter is right: we are composed of vibrating energy; nothing is solid. Lauren and I split a Bang-Bang Chicken and Shrimp. Liza gets a Cobb Salad. Henry gets a Glamburger.

Less than an hour later, we’re stuffed. Half our party has a stomachache. But we must try the cheesecake! Ingenious business model, we say: a restaurant where it’s all but guaranteed that every person orders dessert. It takes us ten minutes to read through the thirty-four varieties of cheesecake and then settle on two, and we all take one bite of each and then box them up. We drive out of the mall as the last light fades.

What does all this mean? Two hundred years ago, this land was wild prairie, and then it was stolen and settled and chartered and paved over and built up, segregated and redlined and rezoned, auctioned off in pieces to corporate bidders, designed and constructed and hand-painted, and now it is the Edina Cheesecake Factory. And all of it, even now, has been done by human hands, built with the labor of God-fearing people, by which I mean all of us. If capitalism replaced our temples with factories, and our factories with malls, then maybe the Cheesecake Factory is all of these things at once. Maybe everything is.

We get home, put the cheesecake in the fridge, and watch the finale of The Bachelorette. I bleach my hair. All in all, a pretty fun night.