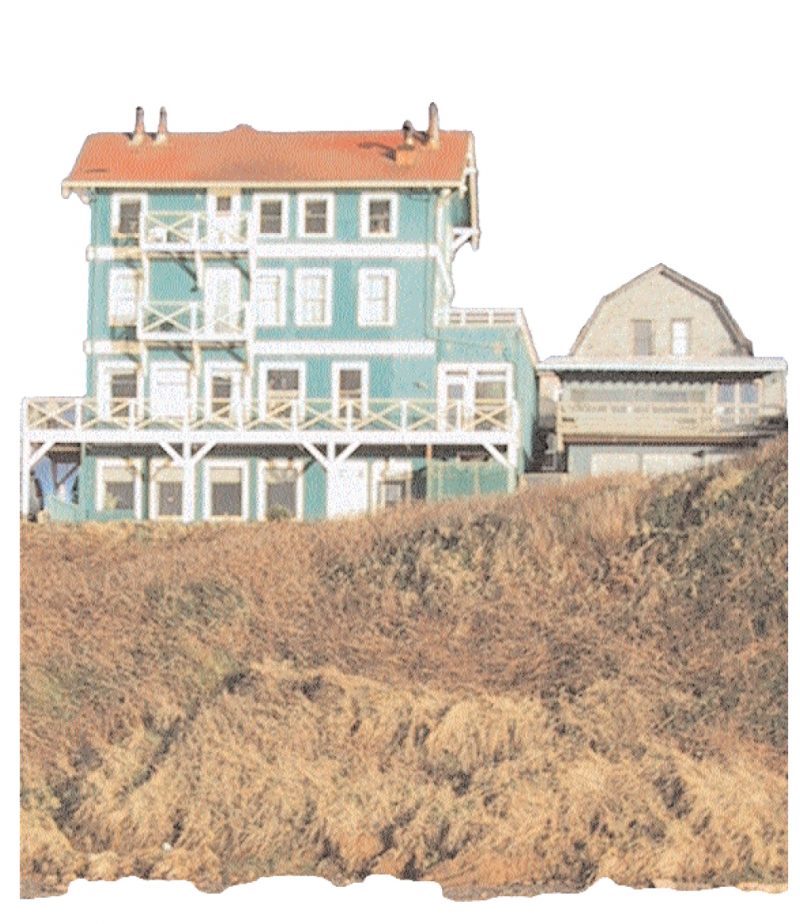

Twenty years ago, when the sheriff in the coastal county of Lincoln, Oregon, wanted to find an escaped convict or a wanted hooligan, the first place he would look was the decrepit four-story hotel moldering along Cliff Street in Nye Beach. Sitting on a sandy bluff forty-five feet above the ocean, the seaside hotel was once an elegant honeymoon destination, reachable only by train.

But like many other extravagant resorts from the Roaring Twenties, the Cliff House, as it was named then, slumped into hard times. During the fifties, it briefly served as the Greyhound bus station for the coastal town. And, by the mid-seventies at any given time about sixty people could be found squatting in the twenty rooms of the hotel.

But all of that was before Goody Cable had her epiphany.

“I was a fool, I had this idea,” she says with gee-shucks country girl charm. “I wanted to be around interesting people,” she explains. “I thought about traveling, but I realized that I like to tell people I’ve been places, but I don’t really like to go.” She decided instead to bring the interesting people to her—to open a B&B for the literary minded.

Goody drove from Portland to the coast three times looking for an appropriate hotel before she saw the decrepit Cliff House. Although townspeople in Nye Beach were lobbying to bulldoze the hotel, Goody was so charmed by its sagging elegance that she immediately wrote a check for $10,000 as a down payment.

“I only had $252 in my account at the time,” she says and laughs. After handing over her check, she drove directly back to Portland seventy miles away and asked her best friend to loan her the money.

Her next step was to re-christen the hotel as the Sylvia Beach Hotel, named after the woman who owned Shakespeare & Co. Bookstore in Paris. She then invited twenty friends to choose a favorite author and design one of the hotel’s rooms in a theme nodding to that author. There is the Hemingway room, the Alice Walker room, and the colorful Dr. Suess room, among others.

With emerald green walls, Victorian precision and a wrap around porch, the most popular room is the Agatha Christie room. Velvet curtains hang floor to ceiling, and tips of brown dress shoes peek out, as if Hercule Poirot himself were hiding there, collecting clues. And, over the years, guests have left a trail of clues throughout the room, each leading to the next, as a sort of meandering, on-going scavenger hunt.

“It’s probably the only hotel where guests bring things instead of taking them,” Goody says proudly. Along with hundreds of books, guests have brought curtains and lampshades. Even Henry Miller’s former housekeeper donated the novelist’s old piano.

The most eerie room is the Edgar Allen Poe, with a pendulum swinging over the bed. A stuffed raven at the foot of the bed is disturbingly animated; its claws tightly grip the wood post and its mouth is wide open, screaming a silent squawk. Goody says that a lot of guests refuse to stay in that room.

But as dynamic as the rooms are, Goody does everything she can to keep people out of them and mingling. There are no TVs in the hotel and all meals are served family-style. A few years into her endeavor, she also invented a dinnertime parlor game, “two truths and a lie,” in which each dinner guest must tell three stories— two factual ones and one based in fiction; the other dinner guests must guess which is real and which isn’t. Goody has always wanted to be an artist and considers the hotel her piece of performance art.

“I’m too gregarious to sit in front of a canvas,” she explains. “Every five minutes, I’d be off asking someone, ‘is this OK?’” The hotel, she says, is her magnum opus. “I like that the guests are part of the art,” she adds.