In January 2023, while waiting to board a plane in Stockholm, I saw how swiftly grief can take hold of a person. In a quiet corner of Arlanda Airport, it unfolded before me like a scene from a movie: an older woman answered her cell phone, listened for a few moments to the voice on the other end, then burst into tears. Her anguish was so immediate, and so visceral, that it could only have been the worst kind of news—the end of a marriage, a dream, or a life. Not just any life, though: one so precious to her that its end was immediately comprehensible.

It was this immediacy that struck me as cinematic, because in real life, or at least in my life, death is many other things before it is something I can cry about. Last year, when my uncle Bill died of a heart attack at age fifty-seven, months passed before I could even conceive of his absence. He meant more to me than any other man, including my father, and yet his death was not at once fathomable to me. It landed with no impact I could make sense of; robbed of the clarifying weight of tragedy, I experienced his death first as an inconvenience. An obstacle. A disturbance that immediately complicated my life, or at least my career, which is what I had instead of a life. The instincts that had helped lift me out of poverty had also made it hard to slow down, and so I lived as if on the run. Next stop: Tokyo, where I planned to cement my relationship with a big American magazine by writing the definitive profile of a major Japanese novelist.

These plans started taking shape in May 2022, when the lease on my apartment in Brooklyn, New York, was coming to an end. The rent was going up so much that renewing it seemed like a gamble I wasn’t likely to collect on. Instead, I decided to do the responsible thing: put my stuff in storage, fly to Tokyo, and spend three months living in a modestly priced hotel while I wrote the story. I’d lived in Japan before, and going back after two years away seemed like the best shot I had at shaking off my malaise. It was also my best shot at producing a story that might take my writing career to the next level—a level that would put me in a position to take the occasional rent increase in stride.

By the end of the first week in June, I’d made it only as far as Manhattan, where a friend had invited me to house-sit while his family was on vacation. I was in their downtown apartment when I got the phone call about my uncle Bill. In bed but not yet asleep, I picked up the second of two late-night phone calls from my mom. Crying, and almost certainly a bit drunk, she told me that her little brother was gone, and all I could say was “Oh no.” When our call ended, a little after midnight, I couldn’t sleep, so I listened to old voicemail messages from my uncle. The most recent one was dated December 25, 2021: “Merry Christmas, Josh. I love you. It’s Uncle Bill. Hope you’re having a wonderful day. Talk to you later. Bye.”

I was meant to visit him three weeks after he left that message, but on the morning of my flight to Juneau, Alaska, I tested positive for COVID-19. I’d contracted the virus while working on a story in New Mexico—my first profile for the magazine I hoped to impress by flying halfway around the world to interview a novelist. While listening to old messages from my uncle, I dwelled bitterly on two unfulfilled promises I had made when calling to say I couldn’t make it home in January: the first was that I would get to Alaska and see him again soon; the second was that he was going to love the profile I had been working on in New Mexico. It ended up being published ten days after he died.

With my flight to Japan booked, and my nonrefundable accommodations paid for in advance, I had a narrow window for making it to the potlatch that would serve as my uncle Bill’s memorial. In Tlingit culture—our culture—the memorial potlatch has traditionally served as both a funerary ritual and a proto-capitalist one; for centuries, our departed were sent on their way with singing, dancing, food, and an ostentatious display of the wealth they would leave behind for others. These days, the banquets tend to resemble any other family cookout, and not many of our people have much wealth to leave behind. A few years ago, I met a man who put off his dad’s potlatch long enough for the carving of a large memorial totem, which struck me as the height of Tlingit opulence. My uncle Bill had left nothing behind, though, because he’d had so little, and because he had shared what little he had so freely. His potlatch proceeded as soon as a small wooden box with an image of an orca was carved to receive his ashes. By that time, though, my window of opportunity for attending had closed.

My mom sent me an announcement for the memorial service, which I perused on my phone during a layover on my way to Tokyo. In a quiet corner of Los Angeles International Airport, a dull pain grew sharper as I stared at the photograph they had chosen. It shows my uncle Bill standing on a beach on the outskirts of Juneau, bathed in sunlight passing through the sieve of an overcast sky. It is October 28, 2021, and in a few hours he will drive me to the airport for the last time. First we drive back to town, though, and along the way a double rainbow appears in the distance. He slows the pickup truck, then eases it over to the side of the road. He makes a dumb joke and asks me to take a picture of the two rainbows. When I send it to him later, I include another photo I took just a bit earlier. In it he is standing on the beach, dressed in jeans and a Carhartt shirt, smiling like he can already see the rainbows waiting just up the road.

I started speaking to my uncle almost as soon as he was gone. It began with the kind of question a child might ask: “What am I going to do without you?” In the days and weeks that followed, I kept talking, not incessantly, but often, and not loudly, but audibly, in the same way I might say “butter” or “milk” while reminding myself what to buy while shopping. The difference was that I was now speaking to some presence outside myself—not a being and not a void, nor a mere memory.

What started as a monologue came to feel like it was one side of a conversation that could never be made whole. I said whatever was on my mind, mostly, but some things came up over and over again. I repeated them while staring at the walls of my hotel room after midnight: “I’m sorry I didn’t come see you one last time.” While walking through Yoyogi Park, in central Tokyo, on a bright midsummer afternoon: “I’m going to miss you so much.” While watching the sun rise over the Sumida River: “Can you believe how beautiful this world is?”

Speaking to the dead can, for a short while, seem to place us outside the laws of nature—outside the rules governing time and space. Memories of the departed inform our conversations with their ghost, and from those conversations, new memories are born. In this way, a person who no longer has a body or a consciousness can be made to cling stubbornly to the present tense. Several weeks after his death, I felt like my uncle was with me in Tokyo, seeing things he’d never had the chance to see when he was alive. His presence was so real to me that there were times when I wanted to turn and speak over my shoulder, as if he were lagging behind, just out of view. This was comforting for a while. But as weeks turned into months, these conversations started to feel less like coping than a form of denial, so I decided some kind of exorcism was necessary. I bought a small black notebook at a stationery store, thinking I might better process my grief by keeping a diary. For weeks, I carried it with me at all times, but the words did not come.

Then, by pure chance, a friend told me about a place called Osorezan. We were talking about how my interviews with the Japanese novelist had finally been scheduled, which meant I was free to leave town until it was time to meet with her. Getting beyond Tokyo’s city limits was something I hadn’t done often enough when living in Japan, which I regretted, and since grief feeds on regret, it seemed like a trip to the countryside might do me good. I told my friend I wanted to head north and escape the summer heat, preferably somewhere out of the ordinary, and he mentioned Osorezan. Before I could ask about its extraordinary moniker—literally “Mount Fear”—he told me: “It’s not a nickname.”

It was his Japanese wife who had visited Osorezan, he told me, and she had never forgotten its otherworldly landscape, which was supposedly a portal to the underworld. Atop this active volcano is a caldera from which eight peaks rise up around a sulphurous lake; one of these is the peak of Osorezan itself, while others, like Mount Jizo, are considered distinct. After digging around online, I read more about the sacred pilgrimage site in the book Discourses of the Vanishing by Marilyn Ivy:

It is a terrain deathly enough to deserve its name, for the object of dread or terror (osore) at this place is death. In northeastern Japan, Mount Osore has long been the final destination of the spirits of the dead, the ultimate home where the dead continue to live a shadowy parallel “life.” Yet more than just the home of the dead, the mountain is a place of practices for consoling, pacifying, and communicating with them, particularly during one delimited period of the summer.

Traveling there during this period, I realized, might amount to something like the potlatch I so regretted missing. Here was my chance for closure, or at least a more appropriate venue for the unwieldy spectacle of sadness—a place where the tears might finally come. I grew eager, even anxious. Speaking to my uncle’s ghost was a comforting habit that raised discomforting questions—not only about memory and how we tend to it, but also about the impermanence of that heightened state of being we call grief. To kill a ghost, after all, we need only ignore it for a little while. Before his departed, I hoped to say all that needed to be said, and so I bought a train ticket to Mutsu, a village that sits at the base of Osorezan, and I gave my little black notebook the name 恐山日記, or “Mount Fear Diary.” In it I would write my thoughts as I prepared for the trip, and would try to put down on paper some of what I’d been feeling since my uncle died. I opened it to the first blank page, and at last the words came.

Tuesday, August 9, 2022 5:11 a.m.

Ryogoku View Hotel, Tokyo

His life ended in a trailer park home in the Mendenhall Valley in Juneau, Alaska. Years earlier, my grandma Rose, his mother, died in the same room, maybe even in the same bed. At the opposite end of the same trailer, my aunt Wendi, his sister, died in her own bedroom after mixing prescription pills with alcohol.

I was twenty-seven when my grandma Rose died, and poor enough that no one gave me a hard time about missing her funeral. A year later, when my aunt Wendi died suddenly, at age forty-two, I was still living paycheck to paycheck, and still unable to make it back to Alaska on short notice. In both cases, poverty absolved me from admitting the truth, which is that I was grateful for any excuse to keep my distance. Since I moved away from home, those who stayed had been through horrors I couldn’t imagine and didn’t want to think about. I could do nothing for them, and little for myself, other than keep my distance from the carnage.

Whenever I did find the courage—and the money—to go home, it was my uncle Bill who saved me from despair. Being strong enough to face the carnage, and to live in its midst, he knew when it was a good day to visit my mom or my aunt or my cousin, and he knew when it was a bad day. He could tell when seeing someone hungover, strung out, or in jail would be better than not seeing them at all. He could sense when I was drifting away, and he knew how to keep me tethered to the family without making me feel like I was on the hook and being reeled in by intergenerational trauma.

I learned a lot of what I know about life from my uncle Bill, who taught me how to fish, how to enjoy nature, and how to get by without a father. When I was a kid, he was a commercial fisherman, with enough pocket money to spoil his favorite nephew. He took me to the movies, to the arcade, and out for burgers at the one fast-food restaurant in Petersburg, Alaska. After weeks or months at sea, he would come back into my life like a whirlwind, and have me over to his apartment to play Nintendo or watch boxing matches on his big color television set. Once, he took me to Seattle, where we visited the Space Needle and looked out on what seemed like the whole world.

After my family moved to Oregon, just as I was starting middle school, I began to spend my summers with Uncle Bill in Alaska. He had moved to Juneau by then, and helped me get my first summer job there. When I got fired, he helped me get my second summer job, and with a minimum of preaching. His life had changed a great deal: after seeing his best friend go overboard and drown, he gave up commercial fishing for a less profitable job in construction. He had also given up the drinking that had failed to help him get over the tragedy. Going to church helped him stay sober in those days, and I often went with him, even though I found it boring.

My own relationship to Catholicism began and ended with a Saint Christopher necklace my grandma Rose gave to me as a child. It was a curious possession—one that I prized as a gift and as a kind of talisman, even though I never came to believe in any church or any god. Jesus and the saints were as corny to me as the rituals of drumming, dancing, and singing I’d grown up with as a Tlingit. Once, and only once, I had felt I was in the presence of the divine: When I was seventeen or eighteen, and visiting Juneau for the winter, my uncle Bill took me to a quiet cove far outside the city, where we stood halfway between the tide and the tree line, taking in the view. It was three or four in the morning, the air was cold and clear, and the moon lit up the stretch of ocean between us and another island in Alaska’s southeastern archipelago. It was a miraculous sight, but not the only thing my uncle had in mind when he rousted me from bed in the middle of the night.

“I thought we might be able to see the northern lights,” he said. Then, before he could explain himself any further, the aurora borealis began slithering across the night sky, and I could see with my own eyes how gods were born.

Wednesday, August 10, 2022 7:52 a.m.

Ryogoku View Hotel, Tokyo

For years, it was more than my career and living overseas that kept me away from Alaska. You never really escape poverty, but not calling home can be an escape from the ceaseless flood of bad news that makes it harder to move on with your own life. It took me years to realize it, but I’m now convinced that this partly accounts for how at home I’ve always felt in Japan: an island country with a predominantly fish and seafood diet where religious and social rituals emphasize animistic gods; a place where people see the mountains and ocean and forest as living beings. Spiritual places filled with ghosts and monsters—the way my Tlingit ancestors saw the natural world.

Living in Japan, I could be foreign, anonymous, and far from family misfortune while enjoying the benefits of a place that felt both exotic and familiar. Furthermore, at matsuri (festivals) I was able to connect with aspects of Tlingit celebrations I’d always been too embarrassed or even ashamed to enjoy—like the Tlingit, Japanese people celebrate community through dance, drumming, chanting, and eating. Like us, they wear ritualistic clothes that hint at a simpler past for these celebrations. Through Shinto rituals and practices, I learned to see the beauty in Tlingit culture and traditions.

Having learned to appreciate my culture, I tried also to better appreciate my family. There are still lots of tears, especially with my mom, but it felt good to be going home more often. It even felt good to cry together. With Uncle Bill, though, there weren’t any tears—we spent our time together laughing, talking, exploring the outdoors, and recalling a lifetime of good memories. Good memories are the only kind I have with Uncle Bill.

On a warm evening in August 2013, while working as an unpaid intern at the Tokyo bureau of The New York Times, I headed to a neighborhood bon matsuri on my way home. I’d been in Japan for about a year, studying at a university in Tokyo, and had come to feel very much at home there. The sense that this was in any way connected to my identity as an Alaska Native didn’t occur to me until late summer, however, when the Buddhist Obon rituals emerge in traditions as varied as dancing at festivals and cleaning the headstones at the graves of one’s ancestors. The realization was fleeting: surrounded by hundreds of local people dressed in summer kimonos, singing, dancing, and eating food sold by vendors, I thought for a moment about some relatives who had passed on.

Two years later, after finishing up graduate school in New York City, I returned to Tokyo for a job as a foreign correspondent at Reuters. My love for the city deepened, as did my love for the neighborhood where I lived. One of Tokyo’s paradoxical charms is that it is a city of vibrant communities built around train stations and markets and temples, each with a sense of intimacy and connectedness one would not expect to find in the world’s largest metropolitan area. My favorite neighborhood landmark was the local Shinto shrine, called Shōin Jinja, after the nineteenth-century educator and activist Yoshida Shōin. In the Shinto religion—Shinto literally means “the way of the gods”—deities are all around us, animating the spirits of objects and places and creatures. After death, mortals like General Nogi Maresuke and Yoshida Shōin can be deified as well, making Shinto an ideal religion for warriors and intellectuals alike.

Throughout the summer and fall of 2015, I visited my local shrine a few times each month, but never gave much thought to what appeal it held for me. It was beautiful, like most shrines, and peaceful. But there was something else I had admired about Shinto since learning about it in a college Japanese literature course—something to do with its emphasis on actions rather than professions of faith, which had always struck me as in invitation to hypocrisy. This emphasis on rituals, gestures, and charms associated with shrines has to do with the shifting importance placed on Shinto and Buddhism over time; centuries ago, when state-sponsored Shinto was abandoned in Japan, thousands of shrines throughout the country were left to find new ways of supporting their activities. What saved them were festivals, where locals spent money on food and on religious charms and services. Adherence to the Shinto religion became entirely transactional, which appealed to me enormously as a lifelong skeptic with Christian relatives who had spent years asking me to profess faith in things I couldn’t bring myself to believe. A general reverence for nature and a few coins in the prayer box was all that Shinto asked of me.

In Japan, my expectations of religious practice were inverted: in contrast to Americans, who profess belief in principles they don’t adhere to, Japanese people often claim not to believe in the Shinto and Buddhist rituals they practice. My own first experiment with Shinto practices came on the second day of January in 2016, when I went to my local shrine and bought a hamaya. These ceremonial “evil-crushing arrows” are made from a narrow cylinder of wood with white fletching and white paper wrapped around the shaft. For about fifteen dollars, you can buy a pair of them to place in your home on a desk or a mantle, where they ostensibly absorb whatever bad luck might befall you throughout the year. When January comes again, and it’s time for hatsumōde—the first shrine visit of the year—you buy a new hamaya and leave the old one in a pile at the shrine, where it will be ritually burned as a means of destroying whatever ill fortune it has absorbed throughout the year.

What seemed like a novel way of participating in local life took on a different kind of significance the following January, when I was away from Japan for an extended work trip in the United States. Unable to bring the hamaya to my local shrine for burning, I kept them with me as I traveled. At first I regarded the fragile objects as precious but powerless, like the Saint Christopher necklace I was given as a child; they were something I could show my relatives as a means of illustrating the charm and exoticism of my new home overseas. But when the new year arrived, I found myself troubled by the unfulfilled ritual: buying the hamaya had somehow led me to buy into the mythology behind it. Like my Japanese friends, I was unwilling to admit that I believed in its power, and yet, I was equally unwilling to treat the object as if it were powerless. And so, through a cynical cash transaction, I came closer than ever before to professing faith in an organized religion.

Sunday, August 14, 2022 10:29 p.m.

Ryogoku View Hotel, Tokyo

On Friday morning I went to see a kabuki play at the Kabukiza Theater in central Tokyo. The second play of the morning/afternoon program was The Game of One Hundred Ghost Tales. August is the traditional month for ghosts, spirits, and murder in kabuki performances. It is also the month of the Obon holiday, for which people throughout Japan return to their ancestral villages and hometowns to visit the graves of their ancestors—to tend and commune with them. It is a festive holiday with lots of dancing and lanterns. The Game of One Hundred Ghost Tales also featured lots of dancing and lanterns. Its theme was the centuries-old tradition of lighting one hundred lanterns and gathering to tell ghost stories and supernatural tales. A lantern is extinguished after each tale, and it is believed that a real ghost will appear after the final lamp goes out; for that reason, one lantern is usually left burning when the evening concludes.

The play featured many tales of famous yurei (ghosts) and yokai (spirits/monsters). One was the kappa—humanlike turtle creatures said to live in rivers, where they eat cucumbers and engage in sumo wrestling. They are said to menace humans and even remove a mythical organ called shirikodama by pulling it out through the human victim’s anus. Kappa have a monk-like haircut, and the bald spot atop their heads supposedly holds water; being that they derive their power from water, they must keep this bowl-like indentation filled with water while away from the river. As such, it’s said that you can defeat a kappa by bowing deeply to him—a gesture of courtesy he’s obliged to return, thereby spilling the water from atop his head and losing his supernatural powers.

Seeing the kappa do his dance, I thought of the kushtaka—a “land otter man” from Tlingit mythology. In ancient times, both spirits must have served a similar purpose: to keep children from falling into rivers and drowning. My grandparents very much believed in the kushtaka. In fact, my grandfather claimed to have encountered one while out trapping on an island near where I grew up. I made him tell me the story when I was young, after hearing it secondhand from my grandma. He did so reluctantly.

When I was five or six, my grandma Rose told me about the time my grandpa Herb encountered the kushtaka. It happened while they were living in Petersburg, when she was pregnant with her first child. My grandfather had taken his skiff to an island across the channel, left it on the beach, and then walked through a valley that cut across the length of the island, where his otter traps were set. My grandmother usually went along with him, but she had decided to stay home that day because of her approaching due date. In previous weeks, her pregnancy had slowed her down on these trips. She found herself stopping to rest more often, each time calling out: “Herb! Wait up!”

When my grandpa first heard my grandma’s voice, while walking through the valley, he thought nothing of it—until he remembered she was waiting for him at home. Each time he looked back in the direction her voice came from, he saw nothing, and sensed only an eerie silence in the surrounding forest. He began rushing through checking the traps, then decided to abandon his work altogether when her voice kept calling out to him: “Herb! Wait up!” He turned to walk back to his boat, but whenever he moved toward the shore, his head grew cloudy. It cleared only when he stopped and took a seat. He felt an overwhelming urge to lie down and sleep. The sense that he was not in control of his own mind ceased after he fired his rifle into the air, at which point the forest exploded with activity, as if every animal on the island were thrashing in the trees and bushes at the same time.

He ran back to the beach, returned home in his skiff, and never went back to the island to collect his otter traps.

Friday, August 19, 2022 2:48 p.m.

Yoyogi Park, Tokyo

About an hour ago, while walking through the wooded areas of this magnificent park encircling Meiji Jingu shrine—a shrine for the Meiji Emperor—I felt very strongly that my uncle Bill was with me. So strong was this sensation that I stopped along a quiet brushed-gravel trail, which I had to myself in that moment, and I spoke: “Well, what do you think of this, Uncle Bill?”

When I last visited my uncle Bill, he seemed in some way depleted. Even in middle age, when his hair had thinned and his trim, muscular physique had started to soften, he’d remained strong. Vigorous. It was clear something had happened since my previous visit, in February 2021, when he’d been healthy enough to hike through knee-high snow for hours as we crossed a frozen lake to reach the Mendenhall Glacier—a spontaneous effort he made in tennis shoes, after I’d casually mentioned wanting to put my hands on the glacier again one day. He did it without breaking a sweat. By the time I made it back to see him, in October 2021, he seemed sluggish and easily worn out. All he would say, though, was that he’d had his gallbladder removed and had to be more careful about what he ate.

But there were signs of something more going on. He’d become obsessed with documentaries about medical miracles and mysteries. On Facebook, he once made a cryptic post alluding to a cure sometimes being worse than the disease. Later, I would learn that he needed surgery for an enlarged heart. It scared him enough that he put it off, and he told just a few people, including my mother. He often refused to talk about it even with her. His behavior was something I could relate to, not having been to a doctor in several years. But it also made me wonder whether a single honest conversation might have saved his life.

Despite his declining health, he remained an outdoorsman, with a sense of the natural world that often seemed supernatural. One afternoon during my final visit, we stopped at a cove outside town, where he took one look at the water and guessed that crab would soon be there. In fact, early as it was for crab season, he said it was likely a few of them could already be found in one particular stretch of water. With my indulgence, he grabbed his fishing pole, and we walked onto a rocky point from which he could barely cast out to the meter-wide spot in question; since crabs are usually caught using baited traps, not fishing poles, I had no idea what he meant to do, until he cast once, twice, three times, before pulling in a crab he had somehow hooked. He smiled like a Little Leaguer after walloping a home run, then threw the crab back into the water. Later he said, “That was so cool,” as if it were a card trick, when in fact it was one of the most amazing things I’d ever witnessed.

Saturday, August 20, 2022 6:51 p.m.

Ryogoku View Hotel, Tokyo

I last saw my uncle Bill in October 2021. It was a ten-day visit. We were supposed to go halibut fishing, but his outboard for his skiff was in the shop for repairs. Still, we saw a lot of each other. We went out to eat often; my mom made beer-battered halibut for dinner at his house one night; and of course we drove out the road to enjoy the woods and beaches.

One night I took him out for dinner at one of Juneau’s fancier restaurants—a place downtown called Salt. I loved being able to treat him to dinner, because he’d bought me so many meals throughout my life. And yet the fact that I now made more money than him did nothing to blunt his generosity. Because I’d only packed tennis shoes, and because it was raining quite a lot during my visit, Uncle Bill bought me a pair of XTRATUF rain boots—a necessary part of the Southeast Alaska “uniform.” They kept my feet dry, but more than that, they made me feel like less of a tourist, like I was not so disconnected from my home and its culture even after two decades spent living elsewhere. “You’re Alaskan,” my uncle Bill told me whenever I said I felt like a tourist. “You’ll always be an Alaskan, Joshua.”

On a cloudy morning at the end of August, I carried my grief to a mountaintop near the northernmost tip of Japan’s main island, at the center of the Shimokita Peninsula, where hell sits in a blackened caldera. Seeing it requires no act of imagination or leap of faith; Osorezan is a place as real as the pain that had brought me there. In antiquity, the Indigenous Ainu people called it Usoriyama, which to their early Japanese colonizers meant “cavernous mountain”—an apt description of the steaming, otherworldly abyss that formed near the peak of this active volcano when it erupted some twenty thousand years ago. Since the late eighteenth century, around the time of its last eruption, it has been called Osorezan, or “Mount Fear.”

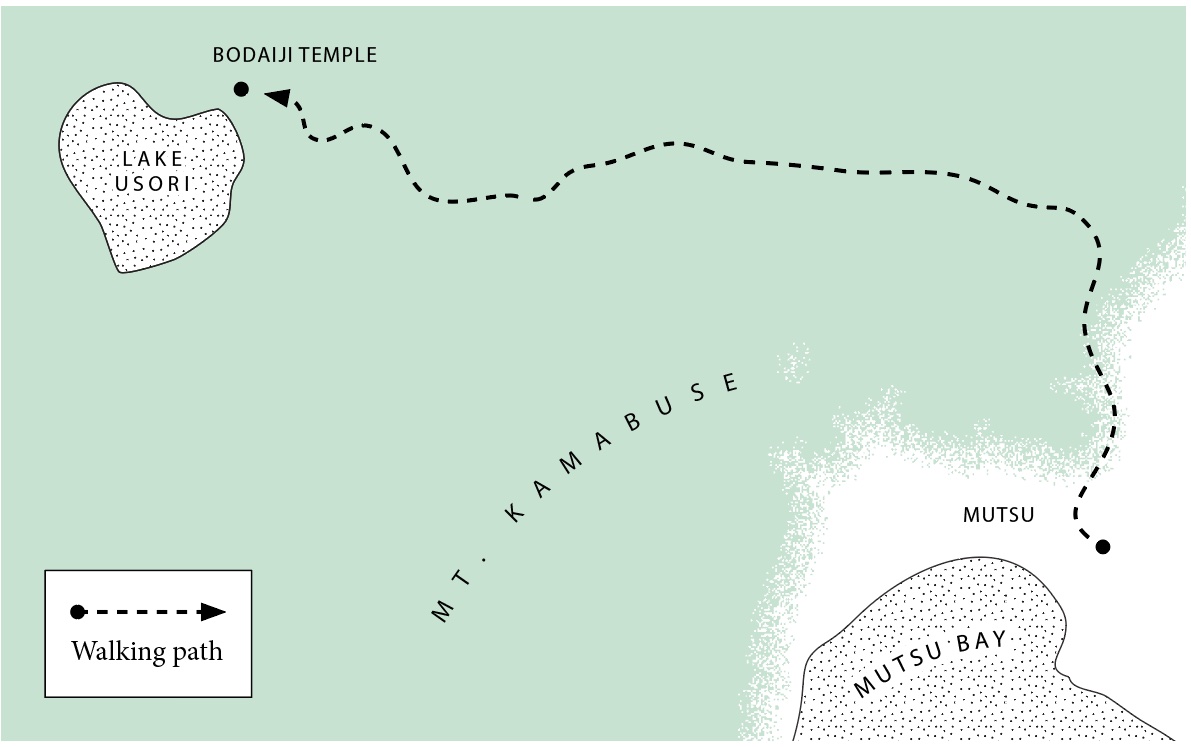

From the nearest train station, in the village of Mutsu, my walk to Osorezan took nearly four hours. The lonesome road was lined with tall trees that seemed to hold back the vast darkness of the forest. Beneath those trees, every few hundred feet, small statues of the Buddhist deity Jizō Bosatsu sat like lawn ornaments keeping watch at the edge of human existence. Behind them was a place beyond serenity, where the quiet of the forest was so intense that the sounds of rushing water and restless animals seemed faintly orchestral; in front of them was the road, where every so often faces stared back from the windows of a small city bus bound for the mountaintop Bodaiji temple, on the shores of the sulfurous and acidic Lake Usori. A tape recording told passengers what they already knew—that “Osorezan is a place with many spirits.”

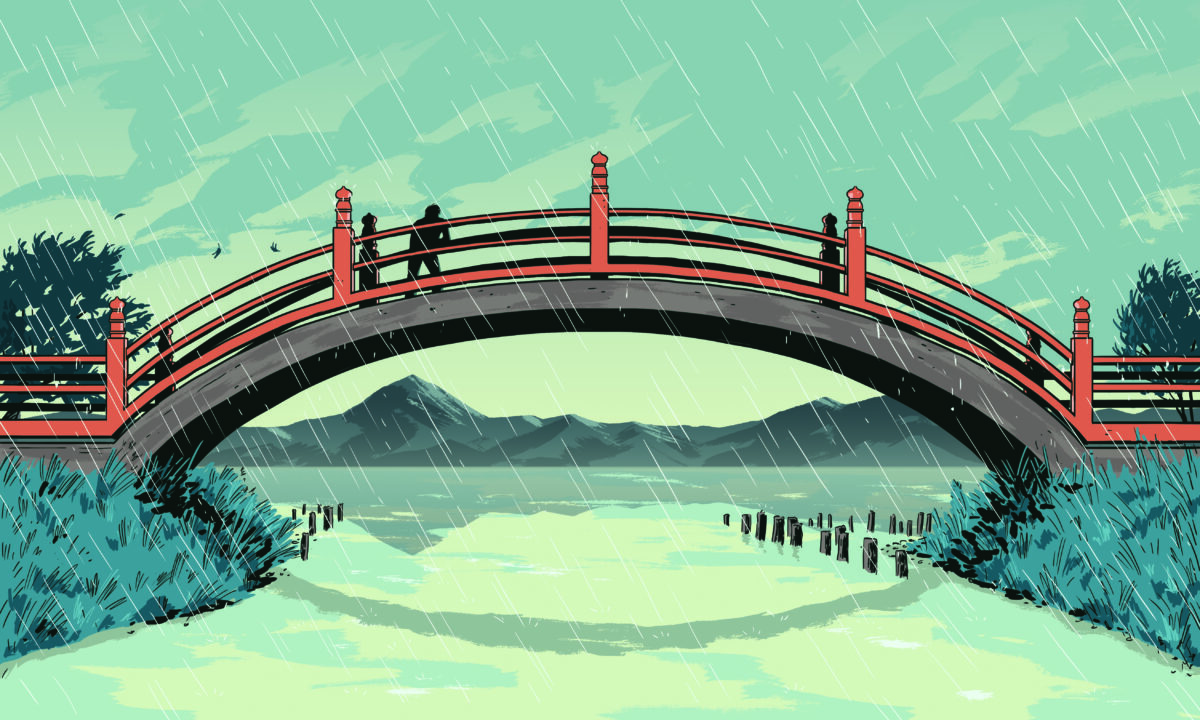

The bus passed me twice as I made my way toward the caldera atop Osorezan, where Bodaiji and Lake Usori sit in the shadow of eight glorious peaks. Damp with sweat and rain, I wondered if the bus passengers could perceive the spirit walking with me. It had been there for eighty-five days, mute, but so real to me that I addressed it aloud. So real to me that the following week, while caught in a sudden downpour on the streets of Tokyo, I would burst into tears and thank it for the last gift it gave me: a sorrow deep enough to draw me back for the next funeral, and the next birthday, and all those other occasions when being together is more important than being free from pain.

Tuesday, August 30, 2022 3:33 p.m.

On Mount Fear

It started raining about 3 km from the bridge that symbolizes the border between our world and the underworld. Not a hard rain: a drizzle that almost made me feel as though I was back home in Southeast Alaska. Clouds filled the sky and mist clung to the surrounding mountain peaks. A short while before you reach the bridge, a powerful sulfurous smell rises up from a creek running toward the bubbling, poisonous lake. After that creek comes a modest river, over which the aforementioned bridge stretches—not a big bridge, but one with an impressive arch to it.

The river is called Sanzu no Kawa, which literally means “River of Three Crossings.” In Japanese Buddhist mythology, it could be compared to the River Styx. Before reaching the afterlife, dead souls must cross the river at one of three points: Deep, snake-infested waters; a shallow ford suitable for wading; or the bridge. How one crosses into the underworld is determined by the weight of one’s sins. The toll for crossing was six mon, according to Japanese Buddhist tradition, hence the practice of placing this fee in the casket of the deceased. Approaching the bridge, it’s easy to see how Japanese came to believe the river beneath me, in rural Aomori Prefecture, was the real Sanzu no Kawa. Its waters are streaked with yellow and brown clay and it smells strongly of sulphur; the river, like Lake Usori, which it feeds, appears calm from a distance, but up close, you can see that the waters are punctuated by small fissures through which water heated by Mt. Osore, an active volcano, bubbles up to the surface. The result is eerie—like a thousand bubbling cauldrons set out upon the lake, shooting steam and poisonous gasses into the air.

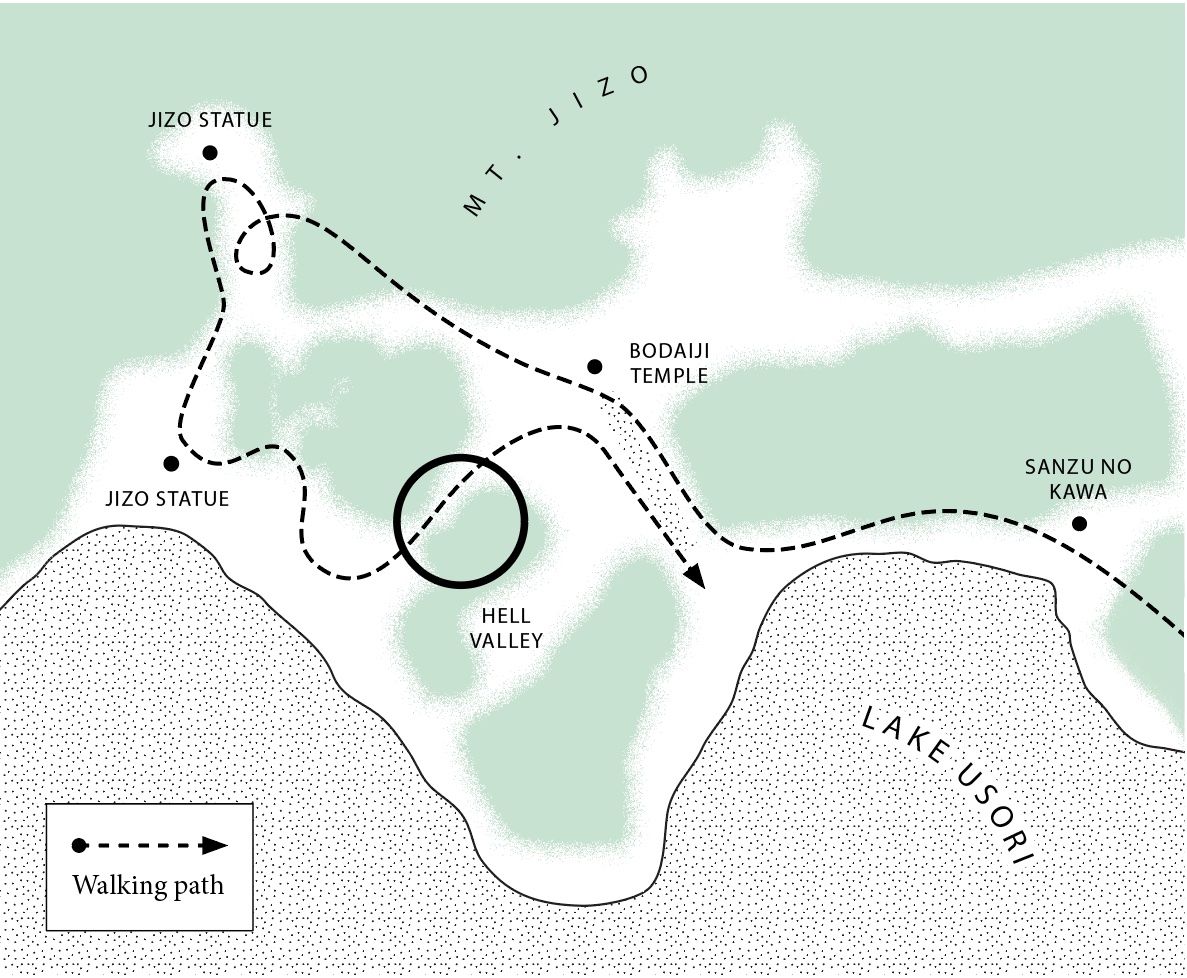

Osorezan’s peak is visible opposite the bridge over Sanzu no Kawa. It is a breathtaking sight—not fearsome at all, but gorgeous. Opposite the peak, just beneath Mt. Jizo, on the other side of Lake Usori, sits Bodaiji Buddhist temple. It’s a short walk past the bridge. Walking to the temple—walking up Osorezan—took about three and a half hours. The road up the mountain is paved but lonely. It is also quite steep. The entire journey ultimately takes 13 hours.

Walking up Osorezan, the forest on each side of the road was dense and dark. Often one side was a valley, while the other rose up steeply like a castle wall covered in moss and dirt and trees. The trees in particular were unbelievably gorgeous. More than once I said out loud: “Have you ever seen anything so beautiful?” Being alone, I took many opportunities to dialog with my uncle Bill. I spoke to him for most of the way up, in fact, though he did not speak back. Mostly I rambled, but it always came back to the same basic thought, which I returned to again and again: “I miss you so much.” Every kilometer or so, stone Jizō statues sat covered in red or white scarves, sometimes with small offerings or piles of stones at their feet.

I was exhausted by the time I reached Bodaiji, where six grand statues of Jizō Bosatsu sit in a line at the edge of the parking lot. At the entrance, I paid 500 yen for a ticket and received a pamphlet along with it. It begins with a section titled “Legend and History,” which suggests that myth is as important as fact within these temple walls:

About 1200 years ago, the Japanese Buddhist priest Ennin was studying Buddhism in China. One night, he had a mysterious dream. In the dream a holy monk said to him: “When you return to Japan, go eastward. You will find a sacred mountain in 30 days’ walk from Kyoto. Carve a statue of the Bodhisattva Jizō and propagate Buddhism there.”

Ennin returned to Japan. In spite of various hardships, he traveled through many provinces on foot in the hope of finding the sacred mountain. Finally he came to the mountainous Shimokita Peninsula. There he found a place which met all the conditions required to be the sacred mountain for which he had been looking. It was this mountain, Osorezan.

Lake Usori sits at the center of the area known as Osorezan. Surrounding it are eight peaks rising up over the white sand and volcanic rock that line the shores of Lake Usori—eight peaks representing, for Buddhists, the eight petals of the lotus root symbolizing the Buddha. “In its central area,” the pamphlet reads, “there are 108 ponds of boiling water and mud, which correspond to the 108 worldly desires and the hells linked to each of them.”

Inside the outer walls of the temple, stone pathways lead to bathhouses and prayer halls. They are as impressive as any temple I’ve seen. But small touches hint at the Buddhist hellscape beyond the temple walls—statues of demons and a grotesque turtle that looks like some kind of monster. Beyond the main hall, which sits at the end of a long, straight path beginning at the main entrance, an unpaved path beckons. The landscape is stark: Massive volcanic rock formations erupt from the earth to create winding walkways leading up, down, left, right; in the shadow of the beautiful green mountain peaks, the landscape only looks more hellish.

After trekking over and across various volcanic formations, many still leaking steam through blackened fissures, I ventured back to the area closest to Mt. Jizō. There the landscape flattened out but remained coarse and strewn with volcanic rubble. Along with miniature Jizō statues, visitors had stacked piles of stones all across this rough and charred terrain. Some of them had the names of lost loved ones written on the stones; others had pinwheels or straw sandals placed alongside them as playthings for the souls of dead children. It is an incredibly eerie sight to behold, however kind the gesture. Beyond this area, near the slopes of Mt. Jizō, an enormous statue of the bodhisattva is perched on a stone carving of a lotus flower, which itself sits on an enormous stone base atop seven stone steps. It is a gorgeous and striking representation of the Buddha rescuing souls trapped between heaven and hell.

Standing before this great Jizō statue, I said a prayer for the soul of my uncle Bill. Turning around, the path that led me there was on my left. On my right was an increasingly sandy path leading toward the shores of Lake Usori. I took it. Along the wide-open path, I was reminded of walking along the beaches of Southeast Alaska with my uncle Bill, exploring tide pools at the point where rocks give way to sand. This landscape looked somewhat like that, but instead of tide pools there were jagged wounds through which steam shot out of the earth and pools where hot poisonous water or mud gathered and boiled.

Several crows assailed one of the many small Jizō statues sitting in this part of the temple grounds. Walking past them, it was easy to see how people decided they were harbingers of something ominous. Beyond them, I found another Jizō statue sitting on a white-sand beach lining Lake Usori. Instead of praying to this Jizō, I found myself talking to my uncle once again, telling him how much I missed him. In the distance, a stunning mountain range stretched out across the landscape on the other side of the lake, with Osorezan itself in the center. It was now raining harder and the mist that hung over the top of the mountain range reminded me very much of Southeast Alaska. Of home.

I began crying—not sobbing, like I had been throughout the day, but really crying hard. Within sight of the beach and the mountain range, I built a small pile of stones. While I did this, I thought of my uncle Bill—of the good and unique and brave and curious person he had been. Kind. Strong. Capable. Honest. Loving. Turning back toward the mountain range, with the pile of stones behind me, I began talking to them. Crying, I said: “I don’t know what I’m going to do without you, Uncle Bill. But if I have to say goodbye to you, I want to do it right here.” My heart swelled to the point of bursting at the beauty of this place. I went on: “This world is so beautiful and I can’t believe that you’re not a part of it anymore.”

For the next fifteen minutes, I stood there crying on the beach, where my tears mingled with the falling rain. Before long, I would have to walk back to the parking area, where a public bus would take me down the mountain. I was too exhausted to walk, and if I missed the bus it would add several hours to my return trip. I wasn’t ready to say goodbye, but I was even less ready to spend several more hours in this haunted place. I stared at the landscape for as long as I could without blinking; I took in the unfathomable beauty of the scenery where my uncle Bill’s pile of stones sat. I wished he could see it all through my eyes, then realized I was seeing it through his.

The path leading back to the main entrance was all burnt rocks and volcanic formations: the very picture of hell. I tried not to look over my shoulder at the mountain range beyond the lake, hoping to preserve the memory of how it looked from the pile of stones I’d made for my uncle Bill. But I couldn’t help myself: Again and again, I turned back for one last look at that magnificent sight. Eventually, I crested a hill made from twisted and burnt volcanic rock. Coming down the other side of it, I turned around for one more look at the last view I would ever share with my uncle Bill—but by then it was obscured by the hill I’d just crossed over, and instead of paradise, all I could see was hell. I kept on walking, though, and soon that, too, was behind me.

This story was supported by the journalism nonprofit The Economic Hardship Reporting Project.