For an editor, dead authors are notably easier to work with than living ones. This probably explains why, in 1731, the London printer Thomas Astley was able to coax a most unusual seventy-four-page tract out of Sir Isaac Newton: Tables for Renewing and Purchasing Leases of Cathedral Churches and Colleges. Since he’d already been dead for four years, it mattered little that Newton was not in the habit of writing lease-calculators: what mattered was that his name could sell any math-related title, and that Sir Isaac was in no position to lodge a complaint about it.

Formally known as allonymic literature, books that steal the names of famous authors are as old as the pursuit of profit in publishing—which is to say, they are probably as old as literature itself. I’ve found, for instance, that a pretty consistent one in six antiquarian copies of Aristotle are not, in fact, by Aristotle at all: they are variants of Aristotle’s Masterpiece, a 1684 sex guide published illicitly in contraband editions up through the twentieth century.

Rarest of all—the truffle of this underground of literary fungi—is the living allonym, the book that steals the name of an author who is still very much alive. The motive is always profit, and the results are always entertaining—if not for these unfortunate authors.

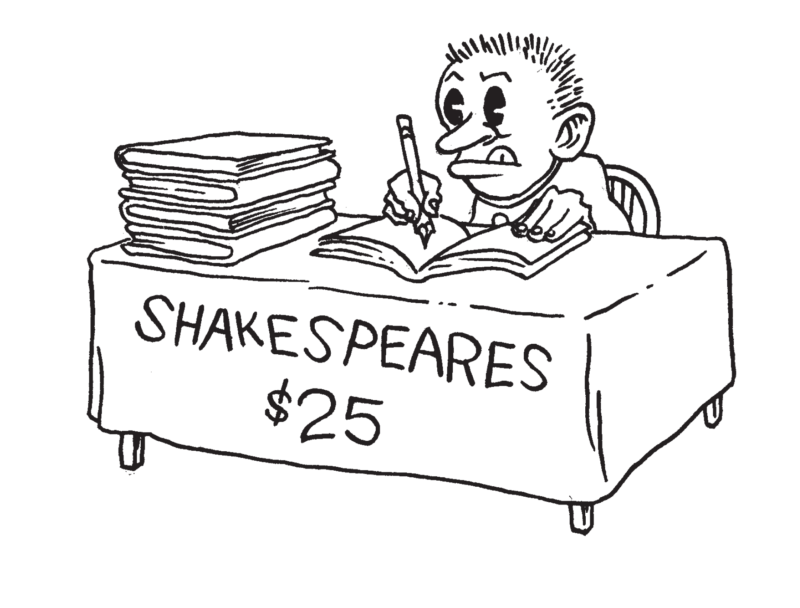

William Shakespeare

The Yorkshire Tragedy (1608)

The tale of a vicious gambler who murders his family, The Yorkshire Tragedy capitalized upon the infamous case of Walter Calverley, who was pressed to death under stones in 1605 for murdering his two sons and wounding his wife. The play, though suitably gory—“I’ll kiss the blood I spilt and then I go: My soul is bloodied, well may my lips be so”—is probably by Thomas Middleton, despite the publisher’s canny use of Shakespeare’s name on the title page. The ploy was convincing enough that even the editors of Shakespeare’s Third Folio of 1663/64 included the play as genuine. Shakespeare was pestered by dozens of other counterfeit attributions during his lifetime, including a bogus poetry volume, The Passionate Pilgrim, issued by London printer William Jaggard in 1599. Despite pirating other editions of Shakespeare, Jaggard landed the printing job for the First Folio of 1623.

Thomas Paine

Tom Paine’s Jests: Being an Entirely New and Select Collection of Patriotick Bon Mots, Repartees, Anecdotes, Epigrams, Observations, &c. on Political Subjects (1793)

Sold for sixpence in London, this chapbook was not exactly the literary crime of the eighteenth century. It maintains the pretence of authorship for precisely one page—the title page—before clumsily referring to Paine in the third person throughout its preface. There are scarcely a half dozen references to him in the remaining fifty-four pages. And like all jest books from centuries that are not the reader’s own, Tom Paine’s Jests is crushingly funny:

A gentleman haranguing on the protection of our law, and that it was equally open to the poor and the rich, was answered by another: “So is the London Tavern.”

Oh, my sides!

A partly destroyed marginal note written in quill on the New York Public Library’s copy hints that the true author also wrote The Spirit of Despotism; the author of that book was one Reverend Vicesimus Knox. This probably makes Tom Paine’s Jests the most hilarious jest book ever written by an Anglican minister.

Lord Byron

Pilgrimage to the Holy Land: A Poem in Two Cantos (1817)

If only Byron had written all the works attributed to him, he would also be our leading vampire novelist—but, alas, The Vampyre was written by his physician John Polidori, despite an 1819 debut in New Monthly Magazine and Universal Register that was plastered with Byron’s name. (Byron’s name was also opportunistically used on an 1829 Spanish edition, El Vampiro.) Byron’s poetic defense of homosexuality, Don Leon—“The muse each morn I wooed, each eve the boy”—is also considered apocryphal. But most nettlesome was Pilgrimage to the Holy Land, a London publication that followed hard upon the success of his first collected Poems; American reprints quickly ensued. Byron denounced the poem as forgery, and years later its authorship was admitted to by the poet John Agg. He blamed the whole affair on his publisher.

Charles Dickens

The Penny Pickwick (1839)

As the first blockbuster novelist in English literature, Dickens spawned a thriving market in convincing counterfeits. (It helped that his own illustrators secretly moonlighted to do the engravings.) The first of a string of knockoffs, The Penny Pickwick was released as the work of “Bos”… that’s Bos, and not Boz. “Bos” was Thomas Peckett Prest, a penny-dreadful hack whose other immortal masterpieces include David Copperful and Nicholas Nicklebery. And who can forget Oliver Twiss? An unamused Dickens took legal action, and a well-thumbed copy of Oliver Twiss found among his effects testifies to many an hour fulminating over his infuriating doppelgänger. Prest would later go on to create a bona fide classic himself: The String of Pearls, better known today as Sweeney Todd, The Demon Barber of Fleet Street.

Howard Hughes

The Autobiography of Howard Hughes (1972)

Cooked up in 1971 by novelist Clifford Irving and Richard Suskind for a $745,000 advance from McGraw-Hill, The Autobiography of Howard Hughes played upon the famous characteristic of its billionaire “author”: his reclusiveness. Namely, Howard Hughes had hidden from the public for so long that Irving bet that even his book would not bring him out into the light of day. His bet was both brilliant and utterly wrong: Hughes broke a decade-long silence to renounce the book in a conference call with seven journalists. Incredibly, Irving then denounced Howard Hughes as the fake. But the jig was up, and Irving landed in jail. Irving’s story is now being released as the Richard Gere movie The Hoax. Irving has complained, without apparent irony, that the screenplay inaccurately portrays his life.

J. K. Rowling

Harry Potter and Leopard Walk Up to Dragon (2002)

In Shanghai market stalls in 2002, customers picked up the next Harry Potter sequel long before any American could. A discerning eye, though, might have wondered at the title of the first chapter: “A Sweet and Sour Rainfall.” Or, for that matter, at its opening lines:

Harry did not know how long this bath would take, when he would finally scrub off that oily, sticky layer of cake icing. For someone who had grown into a cultured, polite young man, a layer of sticky filth really made him feel sick. He lay in the high quality porcelain tub ceaselessly wiping his face. In his thoughts there was nothing but Dudley’s fat face, fat as his Aunt Petunia’s fat rear end.

The above translation comes from Beijing-based computer programmer Russell Young, who goes on to note that from the second chapter onward, Leopard Walk Up to Dragon becomes a nearly direct plagiarism of The Lord of the Rings.

Yu Shiwei

Execution Wins (2005)

Perhaps emboldened by their success—later “sequels” like Harry Potter and the Water-Repelling Pearl have also been rather heavy on mentions of Gandalf—Chinese publishers have gone on to promote entirely fictitious Western authors. One best-selling classic of business advice, Paul Thomas’s Executive Ability, is a five-volume work in Chinese by a Duke University business professor who does not, in fact, exist. Yet a very real Chinese business scholar, Yu Shiwei, has also found himself confronted with books he never wrote. Los Angeles Times reporter Don Lee noted in 2005 that after a lecture in Shanghai, Shiwei was accosted by an eager autograph seeker bearing ten copies of “his” book Ying Zai Zhi Xing (“Execution Wins”). Shiwei, not wanting to disappoint his fan, graciously signed them without a word.