David Baker will never be cool, and his poems admit it: he’s serious, sad, inescapably middle-aged in a rust-belt exurb, where he takes long walks in far-off fields and reads books about centuries-obsolete medicine: “Let this body taketh / away sorrow,” his poem “Resurrection Man” quotes; “Let it asswageth furie of the mind / with our hoard of bones.” When he’s not learning the Latin names of plants, or reading very old poetry, he thinks about how to be a good father, and how to get over (if he can ever get over) what seems to be a recent divorce. Being a husband was hard work, and he loved it; being a former husband is harder, and worse, and the resulting resignation and bitterness make this book sharper and stronger than the calmer poems that Baker has written before.

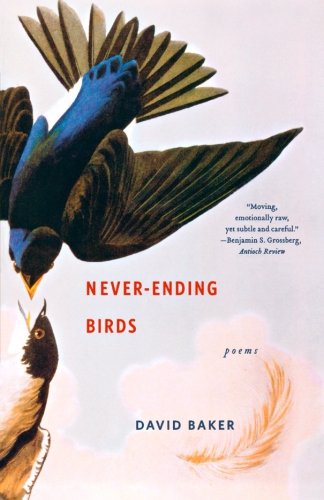

Flip through Never-Ending Birds once, and it seems to be all about human affections, some failed and some salvageable; flip again, and it’s horses, branches, ploughs.The topics stick together thanks to georgic, the classical genre in which hard work on farms stood for responsibility and forbearance among human beings. Baker names Virgil’s Georgics in “Horse Madness,” where “the oval eyes / of goats and sheep / turn rounder as the day/goesdown.” His close attention to what animals do, his deftly incorporated quotations, and his short-lined stanzas (almost—but not quite—in syllabics) might remind you of Marianne Moore, who also used counterintuitive line and stanza breaks to suggest the hard work of observation, of learning to see, not what we expect, but what’s there.

What Baker sees—what surprises him most—is pain: “So much, so much. Like the bulldog / next door, choking itself on a chain / to guard the yard of the one who starves it.” When Baker watches a friend geld a colt (“silver hook / to slit // the tough skin and / tease out the testicles”), the scent brings to mind his best days with his wife, years ago,“us, dancing // in the dining room, hands in each other’s / clothes.” He sees his life, if not his future, in a carcass, with its “aureole of deer guts, bitten / skin, bone.” The coming together of adults, out of loneliness and out of sexual need, seems to Baker as natural—and as unjust—as the way big cats rip up their prey.T he falling-down barns of Ohio, in “Bright Pitch,” represent the human tendency to knock down whatever we try...

You have reached your article limit

Sign up for a digital subscription and continue reading all new issues, plus our entire archives, for just $1.50/month.

Already a subscriber? Sign in