In 1852, Paris was more than two thousand years old, and it was a mess. The streets were too narrow for the traffic, there wasn’t much in the way of lighting, and the drinking water was bad, possibly because the sewer pipes emptied into the Seine, and people got their water from the Seine. There were regular cholera epidemics. From a national-security point of view, the capital was a nightmare, as two revolutions had shown: “A handful of insurgents behind a barricade could hold an entire regiment at bay,” Walter Benjamin noted happily in his Arcades Project.

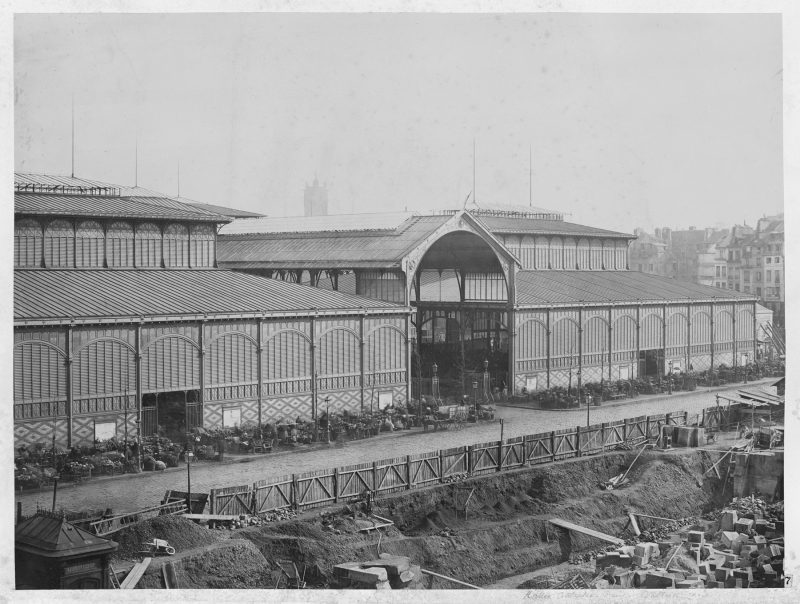

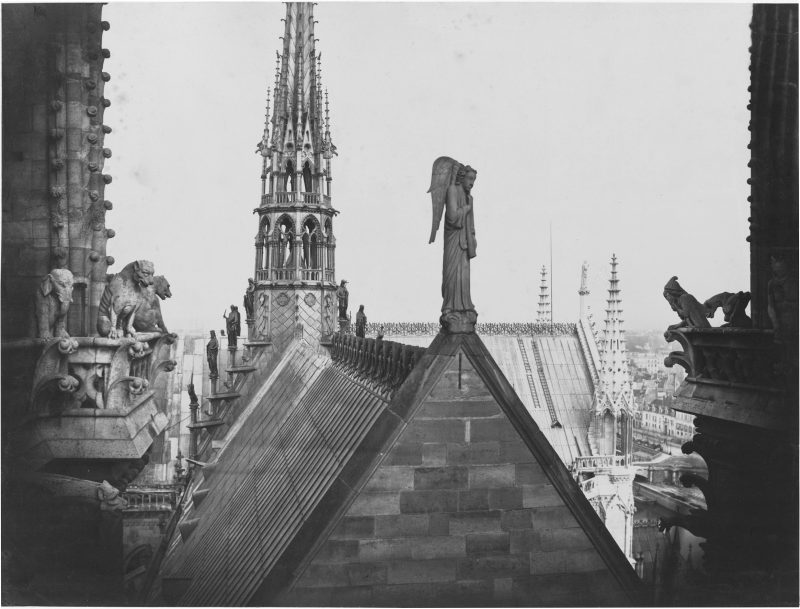

In this context Baron Georges-Eugène Haussmann became prefect of the Seine, the city’s chief administrator. Working with Napoleon III, a fairly authoritarian ruler, Haussmann implemented an ambitious plan of urban renewal: he redrew the map of Paris to make room for modern sewers, modern streetlights, and, above all, modern traffic. Boulevards were cut through the tissue of the medieval city, and the buildings that stood in their way were demolished. Before the old buildings came down, or, in some cases, as they came down, Haussmann’s administration made the curious decision to have them photographed. It may be that even he realized that he was demolishing structures that were, in themselves, not without charm; he surely had the bureaucrat’s self-destructive mania for documenting his own misdeeds. But he also hoped that the photographs would remind the citizens of Paris how much better off they were in the new city than they had been in the old, crowded, impossible one. Starting in 1862, the city hired a photographer named Charles Marville to take pictures of Old Paris. The irony of these photos is that they don’t capture the qualities that made the city unpleasant: Marville worked early in the morning, when the streets were empty, because his camera couldn’t photograph anything that moved; nor could it record the smell of the open sewers, the tanneries, the graveyards with their layers of shallowly buried dead. Marville’s photographs became objects of nostalgia and rallying talismans for Haussmann’s opponents, the people who wanted to keep Paris as it was, although in fact they showed Paris as it had never been: clean, sober, quiet, beautiful, and lost.

The novel today is in the situation of Paris in 1852. It is getting to be an old form, and like Old Paris it creaks under the strain of accommodating modern life. For a century or more we’ve been hearing calls for the novel to be replaced with something more up-to-date, to the point where even cataloging the demands for the novel’s demolition is becoming a quaint activity, like keeping pigeons, or spotting trains. For the time being, we still have novels, but their survival into the present is coming to seem so miraculous that I can’t help wondering what would happen if the form were finally demolished and something new took its place. Is there anything about the novel we would miss? Of course writing, unlike urban development, lets us go back; new literary forms won’t drive Balzac from the bookstore shelves, assuming that there are bookstores in the future, and that they have shelves. So maybe a better question is: is there, even now, some beauty, some usefulness, in the inconveniences of the novel?

What are those inconveniences? The most obvious is probably time. A few years ago I ran into a poet and translator in the stairwell of a semi-neo-gothic educational institution in New York City, and he told me that he had scandalized an audience by telling them that in the future no one would read Proust, because no one would have enough time. Novels grew up in an era when leisure, if not abundant, was at least relatively unscheduled; in an era of universal mutual availability, who will want to—who will be able to afford to—disconnect for long enough to read a novel? What’s worse, from the publisher’s point of view, novels offer a very limited range of transactional opportunities. You buy a book, you read it, maybe you loan it to a friend, and that’s it. Gary Shteyngart gets it right in his dystopian near-future novel Super Sad True Love Story (2011): Lenny Abramov is reading a battered volume of Chekhov stories on the plane, and the young businessman sitting next to him points to the book and says, “Duder, that thing smells like wet socks.” In a world where you get status from owning the latest technology, books are anathema: a sign that one isn’t buying as much as one could. Novels in particular have such power to isolate and immobilize their readers in a time beyond the reach of any networked device that it’s tempting, if far-fetched, to wonder whether the demands for a New Novel might in some clandestine way be demands for an economically accessible novel, a novel that makes room not so much for life as for advertising.

Literature tends not toward action (as the surrealists believed) but toward a kind of silence: this was the insight of Maurice Blanchot, the French novelist and critic, who in the 1950s wrote a series of essays called “Investigations,” later collected in a book called The Book to Come. This was not a Wired magazine–type prognostication on the literal future of reading, or books, or bookstores; Blanchot’s answer to the question Where is literature going? was: “literature is going toward itself, toward its essence, which is disappearance.” It has been going in that direction at least since the early nineteenth century, but it has somehow managed not to disappear yet. This suggests that the state of crisis, of being about to disappear, is habitual for literature, and even definitional. Maybe literature is what is always about to disappear. In The Book to Come, Blanchot has an essay called “Death of the Last Writer,” in which he describes what would follow that as-yet hypothetical event, the last writer’s death:

To the surprise of common sense, the day this light goes out, the era without language will arrive not because of silence but because of the recoil of silence, the rending of the silent density and, through this rending, the approach of a new sound. Nothing serious, nothing loud; scarcely a murmur, which will add nothing to the great tumult of cities from which we think we suffer. Its only characteristic: it is incessant. Once heard, it cannot stop being heard, and since one never truly hears it, since it escapes all understanding, it also escapes all distraction, it is all the more present when we turn away from it: the echo, in advance, of what has not been said and will never be said.

What ends with the death of the last writer is precisely silence: the silence in which it’s possible to concentrate, the silence in which it’s possible to think. If we give up the kind of concentrated abandon we get while reading novels, we will lose one of the last silent places left to us. We will hear the hum everywhere, whether it’s the whoosh of life coming at us in bright splinters or just the fans on our overheated laptops.

Before we run off to found a Society for the Preservation of Novelistic Stillness, however, it might be useful to bring Charles Marville back into the picture. The stillness of Old Paris doesn’t belong to Old Paris; it belongs to Marville’s photographs, from which most human activity has been excluded for technical reasons. If the motion picture had been invented fifty years earlier, we would have a very different idea of Old Paris, and possibly the people who championed it wouldn’t have been quite so outspoken. In the same way, the stillness of reading is not a reflection of a quieter time (when was there ever a quieter time?) but an artifact of the technology of fiction, which works the multiplicity and simultaneity of life together into something ordered, if not always coherent. Our attachment to it is probably connected to the fact that we form our reading habits as children, and the stillness of reading comes to seem like a figure (illusory, though) for the stillness of childhood (also illusory).

In fact, the same could be said about the people who fought Haussmann’s work so bitterly. What Marville’s photos encapsulated for them was the city of their childhood, a city which would of course have vanished whether Haussmann came along or not. Marville’s work gave the champions of Old Paris, who hadn’t grown up with photography (which didn’t become popular until the invention of the daguerreotype, in 1839), the illusion that the city they remembered from their youth could have been preserved. It was almost a paradox: this new invention, the camera, instead of giving them a feeling of discontinuity with the past, gave them a feeling of possible continuity. It was a rare, or maybe not so rare, instance of an invention that could keep things just the same.

The stillness of literature, too, requires invention. One writer who understood this well is Kafka, who, in 1923, when he was forty, and possibly already in a sanatorium outside Vienna with advanced tuberculosis, wrote a story called “The Burrow.” It’s about an animal (because it’s told from the animal’s point of view, we never learn what kind of animal it is) that has dug a labyrinth of tunnels in which it moves around and stores its food. The burrow is the burrower’s life’s work; it has its juvenilia (the entrance tunnels, “which I judge today, with perhaps more justice, to be too much of an idle tour de force, not really worthy of the rest of the burrow”), and its masterpiece, the Castle Keep, a spherical chamber, the walls of which the narrator has packed to stonelike hardness by hitting them repeatedly with its head. The burrow is like a work of fiction, polished by means of repeated cerebral trauma; it’s also a kind of urban space, not entirely like the town and castle of The Castle, or like Kafka’s Prague. It even has a population of “small fry” on which the narrator dines. It’s a cozy place, ideally suited to its creator, but as the story goes on, it turns out that it has a problem: a “faint whistling noise” which wakes the narrator from sleep. The burrower spends a lot of time investigating this noise:

One could assume, for instance, that the noise I hear is simply that of the small fry themselves at their work. But all my experience contradicts this: I cannot suddenly begin to hear now a thing I have never heard before though it was always there. My sensitiveness to disturbances in the burrow has perhaps become greater with the years, yet my hearing has by no means grown keener. It is of the very nature of small fry not to be heard. Would I have tolerated them otherwise? Even at the risk of starvation I would have exterminated them. But perhaps—this idea now insinuates itself—I am concerned here with some animal unknown to me. That is possible. True, I have observed the life down here long and carefully enough, but the world is full of diversity and is never wanting in painful surprises.

Life keeps throwing new, painful things at the burrower, and its burrow is no longer adequate—not, however, to accommodate these new phenomena, but to protect it from them. One might say the same thing about the novelist. From this perspective, the novel is not a mirror walked along the side of the road, as Stendhal famously called it, so much as it is a blindfold—or, better, a pair of noise-canceling headphones, which generate an equivalent but opposite signal to the hum of the world, leaving the reader, for a moment, in silence.* Only for a moment: the world changes, and the novelist, fearfully, blindly, works to keep up.

“Yet it cannot be a single animal,” Kafka writes,

it must be a whole swarm that has suddenly fallen upon my domain, a huge swarm of little creatures, which as they are audible, must certainly be bigger than the small fry, but yet cannot be very much bigger, for the sound of their labors is itself very faint. It may be, then, a swarm of unknown creatures on their wanderings, who happen to be passing by my way, who disturb me, but will presently cease to do so. So I could really wait for them to pass, and need not put myself to the trouble of work that will be needless in the end. Yet if these creatures are strangers, why is it that I never see any of them? I have already dug a host of trenches, hoping to catch one of them, but I can find not a single one. Then it occurs to me that they may be quite tiny creatures, far tinier than any I am acquainted with, and that it is only the noise they make that is greater. Accordingly I investigate the soil I have dug up, I cast the lumps into the air so that they break into quite small particles, but the noisemakers are not among them. Slowly I come to realize that by digging such small fortuitous trenches I achieve nothing; in doing that I merely disfigure the walls of my burrow, scratching hastily here and there without taking the time to fill up the holes again; at many places already there are heaps of earth which block my way and my view.

What is making that whistling sound? Kafka won’t tell us, but it’s hard not to think of Blanchot’s “echo, in advance, of what has not been said and will never be said.” Kafka may not have been thinking about the “death of the last writer” as he wrote “The Burrow,” but he was almost certainly thinking about the death of Franz Kafka, and it’s tempting to hear the whistling as the sound of some kind of Outside, the noise the world will make when Kafka is gone from it. It’s the sound of the missing chapters at the end of Amerika, the sound of the provisional last pages of The Trial… The burrower, responding to the sound, alternates between tearing apart his own tunnels and banging them back into place with his forehead. He dreams of a Castle Keep that would be isolated from the rest of the burrow by “free space”—this is the dream of writing a work that is completely disconnected from the world, completely autonomous—although of course both the work and the Castle Keep have to rest on some kind of foundation.

This frantic activity is the opposite of Haussmann’s urbanism. It has nothing to do with improvement, still less with progress. It is spurred on only by the desire to make something stop, to get to the bottom of it and make it stop. Crucially, the burrower lacks perspective, whereas perspective is what Haussmann’s work was all about. The boulevards built at the cost of so many old buildings connected one viewpoint to the next; they created vistas for the eye, and, if necessary, for the cannon. This long-sighted way of working has its aesthetic satisfactions, but, as Jane Jacobs famously pointed out, it’s a city-killer: think of Robert Moses’s proposal for a freeway-scarred Manhattan, or Le Corbusier’s plan to replace Paris with a ville radieuse of towers stuck like so many first-person pronouns in sterile parkland.

Novelists are burrowers. They work in negative space, not building up but scratching away: crossing out, putting back, crossing out again. If it were useful for them to look down on the world from the height of a plan, or a theory, they would surely do so, but in fact a novel written from that height would itself be only a theory or plan, a space in which it would be impossible to live (or to hide: for burrowing animals, the two are not unrelated). The difference here is one of perspective but also one of speed. In 1857, before Haussmann had completed the bulk of his work, Baudelaire wrote about Paris: “la forme d’une ville / Change plus vite, hélas! que le coeur d’un mortel,” “the shape of a city changes faster, alas, than a mortal’s heart.” Novelists move in step not with the outward forms of culture but with the inward impetus of their dissatisfactions, of which their novels are the echo. This is quite possibly the reason why we still have novels at all. The authors of manifestos can write what they will; novelists will keep deploying characters and plots for as long as people and events continue to matter to them; and if those things cease to matter, it may be that humans have changed so much that the death of the novel will be the least of our concerns.

The odd thing is that the novelist, whose eyes are at best severely shortsighted, and at worst completely endarkened, sometimes sees more than the visionary. I can’t help thinking of a passage at the end of Hawthorne’s The House of the Seven Gables, published in 1851. Clifford Pyncheon, after being imprisoned for thirty years for a murder he didn’t commit, flees the scene of another murder, which he also didn’t commit, with his spinster sister, Hepzibah. The old couple choose to escape by train, a novelty in those days, and in the course of their flight, Clifford, whose sanity has never been robust, engages in a delirious conversation with a fellow passenger:

“Then there is electricity,—the demon, the angel, the mighty physical power, the all-pervading intelligence!” exclaimed Clifford. “Is that a humbug, too? Is it a fact—or have I dreamt it—that, by means of electricity, the world of matter has become a great nerve, vibrating thousands of miles in a breathless point of time? Rather, the round globe is a vast head, a brain, instinct with intelligence! Or, shall we say, it is itself a thought, nothing but thought, and no longer the substance which we deemed it!”

You can hear the echoes of Clifford’s thought to this day, but Hawthorne is hardly drawing a blueprint for the future, and still less for the future of the novel. The House of the Seven Gables is a Gothic romance, a form that was already old-fashioned in Hawthorne’s day; Clifford’s speech presents the world as it might be only to entangle it in the angled attics and low-ceilinged rooms of a mythic Puritan past.

In 1869, five years after Charles Marville started documenting Old Paris, Haussmann was forced out of office by his enemies, the preservationists and the republicans. A year later the Second Empire fell. Novelists rarely have so much effect on the world; and yet it is perhaps not too much to hope that by means of novels, certain categories of human experience might be maintained even in the face of forces which find them inconvenient: a nostalgia for character, that sanitized version of self, might encourage readers to hold on to the idea of their own individual interiorities; a nostalgia for plot, which is human action cleaned up and reduced to a manageable scale, might furnish readers with a belief (delusional, perhaps) in the consequentiality of their own deeds. The burrowers will not win, nor will their frantic efforts ever actually reach the source of the sound, which is overtaking them from the future, but by dint of phenomenal effort they still give us a feeling that things could stay the same, a feeling that we are worth preserving, and that we can be preserved.

The last thing that needs to be said here is that this feeling is, and must be, an illusion. For human beings actually to be frozen as they were at any historical moment would obviously in the long run be a disaster, just as it would have been a disaster for Paris if it had been left in its medieval form. What we require is not stillness but digging; what we can hope for is not to scare the future away but to remain separate from it. This is what happens in a terrible, wonderful passage at the end of “The Burrow”—the provisional end; like many of Kafka’s works, it may be unfinished—when the burrower wonders, for a moment, if the whistling animal, whatever it is, may have heard him, if it may be listening to him:

The more I reflect on it the more improbable does it seem to me that the beast has even heard me; it is possible, though I can’t imagine it, that it can have received news of me in some other way, but it has certainly never heard me. So long as I still knew nothing about it, it simply cannot have heard me, for at that time I kept very quiet, nothing could be more quiet than my return to the burrow; afterwards, when I dug the experimental trenches, perhaps it could have heard me, though my style of digging makes very little noise; but if it heard me I must have noticed some sign of it, the beast must have at least stopped its work every now and then to listen. But all remained unchanged.