I.

I haven’t bought anything in a while. I’m standing in the gift store of the Tate Modern museum in London—the store is housed in a room 115 feet high, 75 feet wide, and almost 500 feet long—and I am shopping. There are items available for my desk (gewgaws and molded-plastic paper clip holders), for my body (witty sayings on T-shirts and pullovers), for the weather (colorful umbrellas), and for the kids (challenging puzzles, card games to increase cultural awareness). But nothing appeals, quite, and so I leave the store and begin to walk up the enormous ramp to the building’s entrance/exit before stopping midway. At the top of the ramp, a couple of children are playing; they’re rolling coins down the concrete, the sound of the money ringing in the echoing hall as though into the deep drawer of a cash register. Mostly, the money veers off to the side, but occasionally a coin rolls toward someone who hears the change coming and, startled, steps aside.

One child, perhaps too small to handle currency, has decided to roll himself down the concrete ramp as though down a grassy hill. Other people are walking backward up the ramp as they leave—many do in this building—to see what they have just seen. Still others sprawl on their backs and lie there, apparently stunned or simply tired.

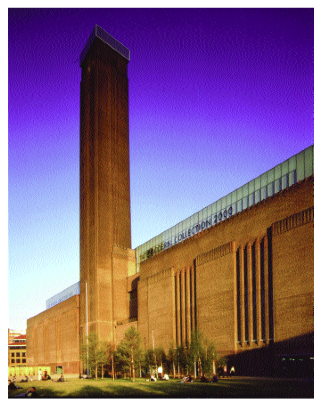

A refitted industrial space, the Tate Modern appeals to one’s sense of historical scale—that is, of a time when enormous buildings were conceived to dramatize human ambition. What was once commercial and industrial has become public, the entrance free to all who desire an experience of the post-industrial sublime. And yet the building resists its urban context—according to one of the visitors I interviewed, from among thirty or so over a two-day span. Jennifer Franklin, a teacher from Toronto, tells me, “It’s the opposite of London… congested, polluted… the space feels light and airy.” Daniel Freidus of San Francisco, who works in telecommunications management, reports that the building is “fine for what it is…. I think that it looks like a hangar, which is fine for a museum.”

Although the Tate Modern might look like a hangar—a truly stunning hangar—the space functions more like an airport. Or an airport and a shopping mall. Which means that the Tate is neither church nor library: in fact, almost all of the megamuseums, the destinations worldwide of millions of art tourists, have abandoned their roles as churches and libraries, in favor of a more democratic approach to cultural commerce. Perhaps this notion of democracy is different from what we’ve been taught to expect, but it’s democracy nonetheless, and our museums are participating in how democracy is changing.

II.

The Tate Modern lends itself to “thick” description, as the ethnographers might say, and tells a number of stories about the cultures in which the museum resides. Of course, one of these stories is of English power and capital, of acquisitions and commissions, and a testament to loot (most museums tell a similar tale). But another tale seems true too. Despite a collection originally strong in the YBAs (the Young British Artists of the ’90s) and sprinkled with spectacular bits of Francis Bacon, the Tate Modern gallery of contemporary and international art since 1900 has become resistant to anthropology, as well as a non-place.

In his 1992 monograph, Non-places: Introduction to an Anthropology of Supermodernity, Marc Augé examines sites where the prospect of individualized experience has been replaced by interchangeable experiences of solitude. Augé argues that some places are anthropological, by which he means they’re local and related to the culture in which they reside; and other places are really “non-places,” where a lack of communal experience creates a supermodern anxiety.

The non-places identified by Augé are areas of transit and commerce, including shopping malls and airports, where generic signifiers categorize our fundamental isolation. An airport is not an environment without meanings, but one airport terminal may well mean the same as another; the airport’s lack of relationship to specific cultures and local experiences makes the building a “non-place.”

Consider the interchangeability of the twenty-first-century exhibition, how the artwork itself can be viewed anywhere in the world, no matter whose money underwrites the show. Consider the bag checks. Consider the fact that while one views a painting, the viewer him- or herself is being recorded and televised on a security camera, which means being evaluated in terms of one’s threat profile. Consider the branding of the museum, the plastic bags with which viewers parade home. And thus how like the airport and shopping mall the museum has become, the viewer’s entry into each of these non-places validated, her or his identity encoded and affirmed.

Which means that we’re alone in public once again. However, there’s a significant difference between being alone in public in an airport and being alone in public in an art museum. In a museum, the viewer performs the social functions of the art devotee—respectful silence, the appropriate apology for crossing in front of a working copyist, the mostly clockwise moving through a room—and then shuffles off to the gift shop. But most important to this analogy, in a museum all of these behaviors remain singular, and specific to each viewer. As a result, the work of art still offers each of us a state of intimacy in addition to our supermodern anxiety, a relationship that invokes our identities even while it commodifies our desires within a non-place.

III.

The idea of the museum as a non-place may be understood as American in its origins, both as an exportation of Hollywood aesthetics—especially in relation to the notion of “spectacle”—and as the codification of American know-how. From the advent of the blockbuster traveling exhibitions in the U.S. in the 1970s—including the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s King Tut show, which was followed by the Van Gogh show—to the emergence of the “Bilbao Effect” in museum architecture, the art museum has become a kind of performance space or even film set, a spectacle indebted to American technology and visual culture.

What seems true of this Americanness, too, is that all of these phenomena resist anthropology; Gehry’s Bilbao could be anywhere in the world, stunning and brilliant, and nonetheless in its design a combo of Fantasia and CGI. The Bilbao could be in Santa Monica as easily as the Getty could be in Spain. Which means that the experiences of viewing art in such spaces—astounding and distinct though their architectures may be—have become, in effect, interchangeable.

But the individual who stands before a Rothko in the Tate Modern remains capable of having an intimate experience with the work of art. We are there, and there is the Rothko, not in New York in 1953 but in London in 2007, and while the context has changed, the change only serves to heighten the viewer’s solitary relationship with the work of art. The displacement of the Rothko, that is, the very fact that it’s not in New York, amplifies the individual’s experience, all context effaced.

Art museums have become non-places where our loneliness and anthropological alienation foster intimate relationships to individual works of art.

IV.

The Tate Modern stands Bankside, on the south bank of the Thames, in a neighborhood built by the Romans shortly after they overran London in 43 A.D. For centuries a popular area with various big Whigs and too-too Tories, Bankside became a red-light district by the sixteenth century, and the site of Shakespeare’s Globe Theatre in 1598. For over two hundred years—until the bombings of London during World War II—Bankside was a slum. Then, as the city was rebuilt, the architect Sir Giles Gilbert Scott (known for his ubiquitous red telephone booths) designed the Bankside Power Station as a kind of “new cathedral” across the Thames from St. Paul’s, an effort that did little to reconstruct the neighborhood. Moreover, obsolescence loomed as always, and by 1982 the power station had been mostly decommissioned.

When Boston-based architects Jacques Herzog and Pierre de Meuron converted the power station to house the Tate Modern’s art collection, and Sir Anthony Caro built the Millennium Footbridge to span the Thames from St. Paul’s to the museum, the much-publicized hope was that these structures would revitalize Bankside. The museum directors projected an annual attendance of 1.25 million, and pledged that the Tate’s new, radical exhibition practices would be accessible to museumgoers. But as has been the case with museums worldwide, and perhaps especially so for the Tate Modern given the lack of an entrance fee, the institution has been overrun. The Tate Modern averages almost 5 million visitors a year (as compared to MoMA and the Pompidou, both of which attract between 2 and 3 million visitors annually) and has become “the third most popular free visitor attraction in London,” according to the museum’s accounts.

And now the Olympics are coming to London in 2012, which means that it’s a good time to raise money for high-profile local projects. So Herzog and de Meuron—recipients of the Pritzker Prize in 2001—are renovating again and building too, to increase exhibition space by 60 percent, double retail space, add a theater and installation spaces, and construct a somatic, Gehryesque, devolved pyramid on the south side of the power plant.

It’s also a good time to be global. “Next Generation Tate,” a publication of the museum’s press office, identifies four “ambitions” for the institution between now and 2015. These goals include international aspirations: to “reflect global practice,” the museum will strive to present “a much broader worldview of visual culture,” and thereby “develop [the Tate Modern’s] status as a world leader and centre of excellence in museum and gallery education.” Acquisitions have been made in the areas of digital media, film, and video; the diversity of these purchases has been much trumpeted by the museum’s PR flacks. With such booming attendance, the Tate has become a twenty-first-century version of the nineteenth-century British Museum, by putting on display the world’s treasures—legally acquired—for a huge international viewership.

In a city known of late (unfairly or fairly) for racial conflict and terrorist bombings, the institution of the Tate Modern serves an important local function. Arguably, the future reputation of a society depends upon its relationship to culture. And so, with the Olympics on the horizon, the benefits of globalism justify to Londoners the museum’s expansion, as well as the 7 million pounds invested by the London Development Agency to “kick-start” and “help fast-track the scheme”; an institution so culturally hip will undoubtedly epitomize the values of its city. Nonetheless, by definition, a museum of contemporary and international art with a diverse collection stands apart from its local context, and at a remove from its anthropological setting. As such, ironically, as a successful art museum in London the Tate Modern rewrites the social contract between the city and its people: the non-place that is the democratic, global museum represents and stands apart from the democracy in which it resides.

Another irony: the building of the Tate Modern’s collection has been funded in part by an art heist and insurance claim. In 1994, prior to the renovation and refit of the Tate Modern, two paintings by J.M.W. Turner were stolen while on loan to a museum in Germany. The Tate Gallery (which includes three other Tate museums) received £24 million in insurance for the loss. The museum trustees negotiated a buyback provision with insurers in 1999 for a considerably reduced price should the paintings reemerge, which they did in 2002. The paintings were promptly restored to the Turner Bequest—but as a result of the buyback arrangement, £10 million of “profit” became available, and have been designated by the museum’s trustees as the Collection Fund.

V.

When I do exit interviews in museums I approach potential visitors, identify myself as a “reporter,” show my press pass, and request a few minutes of the person’s or persons’ time. I ask the following questions, mostly, with a few other questions at the ready:

- Where are you from?

- What is your profession?

- Is this your first visit to the museum?

- What do you think of the museum?

This fourth question usually inspires a number of follow-up inquiries regarding the galleries, the special exhibitions, the architecture, etc. Then I move on to these questions:

- Did you buy anything? If so, may I see?

- Do you consider yourself a collector of art?

- What art do you collect?

- Where do you buy your artworks (or wall furnishings)? How much do you spend on art—or how much would you spend?

- Upon entering your apartment or house, what work of art would

I see first? - Do you have family photos hanging in your apartment or house? If so, where?

- Where do you hang your mirrors? What works of art can you see in your mirrors?

- What percentage of art in your apartment or house has been individually produced by an artist?

- What’s your favorite work of art?

- Do you own works of art that you hang up prior to the arrival of a specific guest?

Here are a few generalizations based on my exit interviews thus far:

People who visit modern art museums, even those museums that charge no admission, are a relatively self-selecting demographic; on the whole, the people I interview care about art in some way, even if they loathe what they have just seen, which does happen. Museumgoers tend not to be neophytes. These people can’t afford to buy original art—which is probably true of most of us—unless the works are those of a friend or acquaintance. Many of my interviewees own various items (masks, textiles, prints, etc.) from around the world, and often can tell the story of how and where the works were acquired but cannot account for the provenance of the works themselves. Many people live with reproductions of their favorite works of art, but have never seen the originals. Many people buy reproductions of works of art in museum stores; the images they favor are likely to be of works of art not on display in that specific museum. Almost no one believes that any work of art she or he owns might be visible in a mirror at home.

Here’s an aside:

In the course of interviewing museumgoers, I have been escorted from the premises only once, by the local police and museum security at the Coca-Cola Museum in Atlanta. I made the mistake there of asking a guard if the original recipe for Coke did in fact include cocaine.

Here’s a list of statements made by museumgoers I interviewed in London:

This is the biggest room I think I’ve ever been in.

The museum’s accessible. It’s open. You feel the place is full of people.

I could buy loads of stuff if I had the money.

Now that we’ve got a family, we’re more inclined to hang up art.

The industrial architecture is born of an age when we were building our country, and now we’re using it in a way to consolidate our culture.

I thought about buying the book on Turner. I’ll probably do it when I need it.

On my wall? Things from religious festivals. Things you can’t miss.

I like the fact that you can give it a meaning of your own.

I wanted to remember the museum.

VI.

The experiences available to the individual art-viewer have become more organized than they used to be. “Salon-style” displays—the paintings hung one above the other on the same wall—have yielded to white walls and track lighting. Now, with the recent rehanging of its permanent collection, the Tate Modern has challenged anew how an individual work of art might be viewed.

The Tate Modern’s displays are organized around central works, a few seminal pieces that might be seen as important, with other works from the same period on view in nearby rooms. The eclecticism strikes the viewer first—how do these works relate to each other? Even savvy art-viewers have been stumped by the results, as David Byrne noted recently on his blog: “It was the weirdest mishmash of a show either of us had ever seen…. Huh? Maybe there was some intellectual or academic construct at work here, some thread tying this disparate work together, but it remained invisible to us.”

But the didacticism of exhibition practices isn’t always obtuse; to move from a Monet to a Rothko makes an effective argument about influence, and about the latter’s explorations of landscape, space, and the horizon. Sure, the argument’s overdetermined—especially when both paintings are pea green—but it also makes sense. By mostly rejecting the idea that art happens in ten-year increments, and that movements may be seen as twenty-year events, curators at the Tate Modern offer us substantive historical and conceptual matter. The new exhibition practices serve the non-place of the collection well.

In a keynote address at CIMAM—the International Council of Museums’ annual conference for museums and collections of modern art—held at the Tate in November 2006, Scottish novelist Andrew O’Hagan commented: “We now live in the era of fake consensus, or phony populism, a condition in which galleries and homes are seen to succeed best where they manage feelings of non-difference. The use of public space…. is too often promoted, even if only subconsciously, as an occasion for the erasure of private passions and a usurping of the concerns of discrete individuals.” Does the didacticism implicit to the Tate Modern’s exhibition practices succumb to this erasure? I don’t think so—mostly because I’ve talked to museumgoers worldwide for the past few years. My evidence is anecdotal. It’s possible to read comments made by my interviewees as “managed feelings of non-difference,” but to do so misses the depth of those specific, discrete feelings. So many of the people with whom I spoke were moved by what they’d seen; to be so moved, in a public space, seems to me an act of self-determination. But the issue’s tricky: at some point, the exhibition practices, the non-place of the museum proper, and the consumerism may well yield to group-think founded upon erasure.

The Belgian political philosopher Chantal Mouffe has considered of late the question of public art, and especially the notion that an institution institutes a certain kind of person as well as a certain kind of democracy. Mouffe’s notion of demos precludes ethnos: She argues that citizens of an effective transnational political community need to reject local pulls of self-interest. As a “radical liberal democrat,” Mouffe recommends that local differences become multiplied by governing institutions; the more differences exist within a community, the fewer us-them relationships will divide passions. Her arguments—what she calls “agonistic pluralism”—propose to foster difference, an idea bordering on the Pollyannaish but striking nonetheless.

Mouffe’s notion isn’t new to politics, but it seems new to art museums. Increasing diversity within acquisitions and exhibitions has been a priority of contemporary art museums for the past twenty years. But diversity and globalism are different ideas, and they institute different viewers and engender different political notions—one divisive and the other inclusive. In a sense, by effacing anthropology, the non-place of the Tate Modern has traded diversity for globalism. As a result, the transnational viewer, alone in a gallery where a Monet and a Rothko hang, and next to an installation featuring artists such as Maha Maamoun of Egypt and Osman Bozkurt of Turkey, may well be a new member of a new democracy.

VII.

The Romans overran Bankside. The Romans settled, imposed their laws, enslaved locals, executed prisoners, and invested in the development of the neighborhood. Now the art tourists are performing a kind of conquest. The tourists come and go, speaking of Rothko; they take home a poster or a T-shirt or a coffee table book on Dalí and film, spend money, invest in the development of the neighborhood. The tourists finish at the museum and, soon enough, they go to the airport, from non-place to non-place. They reconvert their currencies.

But something potentially momentous has occurred between tourists too: the experience of art-viewing in the non-place of the megamuseum has a kind of conspiratorial social dimension, the affective responses of viewers externalized, all feelings felt in public, even though we’re alone. We make eye contact with others; we apologize and duck our heads. Sorry for standing between you and the wall. Sorry that I stepped into the path of your intimacy.

VIII.

Here’s another irony, combined with an aside: During my three-day visit to the Tate Modern, a team of market researchers from the firm of Ipsos MORI was also conducting exit interviews of Tate visitors. There we were together on the ramp in Turbine Hall: freshly scrubbed, neatly attired, and properly credentialed interviewers. Twice during my work, the Ipsos MORI team approached me and requested an interview, which I thought to decline given my semiprofessional relationship to the institution. At last, though, I stood nearby while a friend, the painter Jesse Aldana, answered the Ipsos MORI survey—admittedly, for me to eavesdrop.

It turns out that we interviewers aren’t really so different. The museum wanted to identify its demographic, and I wanted to establish some version of the same. While my inquiries probably weren’t conducive to number-crunching, and I didn’t have a pamphlet to distribute as a door prize, I was also asking marketing questions, even if my concerns were ultimately related to issues of visual culture and democracy rather than use value and spending practices.

A small discrepancy seems worth noting, though, one that I discovered later upon re-reading my notes—perhaps related to the underwriting of the Ipsos MORI research. In the Tate Modern’s description of its expansion project, available on the museum’s website under the heading “Urgent need for more space,” the PR info states, “Many of the comments made by visitors each month refer to the congestion within the building.” Jesse Aldana was asked neither about viewing art nor about the congestion; Ipsos MORI only wanted to know what Jesse liked. I think we call this spin.

At times, one of the Ipsos MORI interviewers would drift down the long entrance ramp and pass me, apparently to have first crack at the visitors as they left the gift shop. When I saw this, I would sidle down the ramp myself, and maneuver to be there ahead of the competition. Whoever reached the bottom of the ramp in Turbine Hall first would grudgingly smile at the other and trudge back up the ramp to begin again.

IX.

There’s a woman who buses tables for an hourly wage on the second floor of the Tate Modern, where a documentary on Salvador Dalí is being screened for café patrons. As a result of repeated exposure, she comes into contact with the artwork more than most curators do, and develops a kind of expertise as a viewer. I wonder if her relationship to visual culture has changed at all as a result and how so. I wonder if she hears the voiceover from the film when she sleeps.

I lean against a wall and watch the video. There’s the famous moustache of the internationally known roué; there’s footage of Dalí being interviewed by a talk show host, and flirting with another guest by announcing, “It’s the first time in my life that I find a woman comparable to women of the Romantic period.” Near me in the café, a group of German teenagers snaps pictures of each other, cell phones taking pictures of people holding up cell phones. On-screen, the footage of Dalí changes to that of an ad for Braniff International Airways, one that apparently featured Dalí. The artist enters the cabin of a plane and says to the stewardess, “When you got it—flaunt it!” As the line is spoken, the café worker looks up at the German teens, shakes her head, moves on to another table. Dalí next appears on-screen wearing a bullfighter’s hat.

Museum guards also qualify as viewers with a peculiar expertise. I was once informed by a guard at the Guggenheim Las Vegas, as he watched over a show of motorcycles, that he had to keep a particularly close eye on older women, who, among the exhibition’s visitors, were most likely to touch the displays—and a few had even tried to climb up on the bikes. He thought the motorcycles were pretty. The money was good, the job easy. I wanted to know what he hung on his wall at home, and I asked if he had purchased a poster of some kind, or even just a memento from the motorcycle show, but he said no, he would remember the job.

The Danish artist Olafur Eliasson’s 2003 installation of The Weather Project in Turbine Hall attracted 2.3 million visitors over a period of six months. According to the Tate’s figures, on the final day of the show more people visited the museum than visited Bluewater, the largest shopping complex in Europe. (One of the products sold by the museum store in conjunction with the Eliasson show was a large golfing umbrella that “reveals a message when wet by the rain.”) For an institution of contemporary art to trumpet success in comparison to a mall seems fitting; approximately one in six people I interviewed came to the Tate Modern to shop in the museum store and didn’t enter the galleries at all despite the free admission. Maybe it’s perverse of me to say, but I wonder what kind of responses Ipsos MORI would get to their exit interviews if the placards that described each of the artworks in the museum included the monetary value of the work. Would anyone say, I like the fact that you can give it a meaning of your own?

A final aside:

The same café dominated by the preening leer of Dalí connects to a balcony that faces the Thames. There, a photo shoot was being held, watched over by a curator of the museum’s website services. I inquired, and was told that the crew was shooting stills for a storyboard of a short film, “sort of a Romeo and Juliet,” a pilot project designed for viewing only as output onto mobile phones. Not quite a podcast, not really a film… the details were hush-hush, the director hesitant to share with a reporter the next best thing. The German teenagers left, the café workers bused their tables, Dalí smiled at Juliet, Romeo stood on the windy balcony outside, his shirt rippling, his gaze unfocused at those in the café.

It’s all a spectacle, I thought. I might have been in Starbucks at an airport. I might have been in London.