When Arnold Odermatt’s black-and-white photographs of automobile collisions appeared at the 2001 Venice Biennial, almost no one in the visual arts world had heard of the retired Swiss police officer. The Biennial’s curator, Harold Szeemann, first encountered Odermatt’s photos a few years earlier, when they were on view at the police headquarters in Frankfurt, Germany. If the discovery wasn’t exactly accidental—the visit was urged upon him by Odermatt’s son Urs, a film and theater director and protégé of filmmaker Krzysztof Kieslowski—the find itself was real enough: a compelling body of work that might otherwise never have seen, at least by international art standards, the light of day.

Odermatt, born in Oberdorf, Switzerland, in 1925, was already a camera buff when he joined the Nidwalden canton police force in 1948. He began using his Rolleiflex to photograph accidents as a way of supplementing the usual police reports, and continued the practice for the next forty years, until he left the department, in 1990. As one reviewer has written, he had “little apparent purpose beyond satisfying a gradually developing sense of how he thought such pictures should look.”

Judging from Odermatt’s book of these photos (Karambolage, or Collision, Steidl, 2003), he thought they should look well composed, rich in detail and value range, and, perhaps, with a kind of solemn respect for what had happened on the road, handsome. As requisitely noted by art writers, the crashed cars have a sculptural quality. Some of the best images, however, offer a broad, elevated perspective—Odermatt often shot from a tripod mounted on top of a VW bus—that places the crashes within a larger landscape: a long stretch of highway, an Alpine valley, the crossroads at the edge of a village. The human error, the loss of control, and the violent physical forces that caused the damage are gone. The wrecks are not only incongruous with their more peaceful, less erratic settings, but absurd within them, and somehow there’s greater melancholy for it.

Since Odermatt’s first major appearance in 2001, he has had solo exhibitions at the Art Institute of Chicago and at venues in New York, Paris, Geneva, Berlin, and Madrid. He’s mingled and posed for photos with film director (and photographer) John Waters at the Winterthur photography museum—their exhibitions received double billing there in 2004. And the car-crash images were recently chosen by the post-rock band Tortoise for use on the packaging of the CD/DVD box set it released this past August.

Along with the notoriety, inevitable questions of intentionality have been raised. Some critics suggest that Odermatt’s photos shouldn’t count as art, since he didn’t intend them that way. Of course, this is really a charge aimed at Odermatt’s curators and dealers and, by extension, at Odermatt’s son, not at Odermatt himself. “Never in my dreams did I see myself as an artist,” the photographer has said. “I worked as a craftsman.” But given how highly and happily democratized the gallery world has become in recent years, this kind of distinction seems to matter less and less. Besides, even if intent is a necessary condition of art, it is not a sufficient condition of good art.

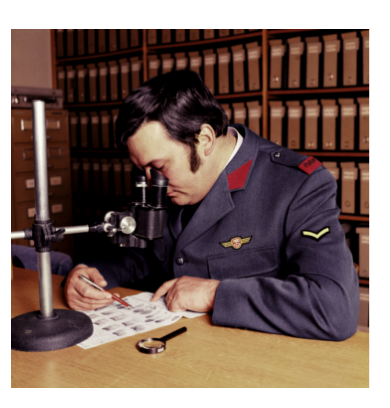

Some of the exhibitions of Odermatt’s photographs in the last few years have included samplings of another, very different line of his work. During the ’60s, ’70s, and ’80s he spent a great deal of time staging and photographing quotidian scenes of policemen in action, using his department colleagues as models. A new book called On Duty (Steidl, 2006) collects more than two hundred of these tableau images—in vivid and verging-on-false color—of policemen pretending to do the things they do every day. An officer uses a broom to sweep snow off a highway sign. Another takes the fingerprints of a perpetrator (whose face is outside of the frame). A helmeted policeman demonstrates a motorcycle maneuver as three others, lined up, look on. Others operate Teletype machines, stamp passports, participate in lifesaving drills, use file drawers, patrol lakes in boats, direct traffic.

Some of the enjoyment that can be had by looking at these police-work photographs is the kind one experiences when looking at vintage corporate filmstrips or other old promotional material. Since Odermatt evidently wasn’t being ironic, or going for a retro look, the staged photographs have also caused some debate. “Here one really does feel that art status is being retroactively endowed in the absence of sufficient intentionality,” wrote Artforum’s Barry Schwabsky about the police-work photographs included in the Art Institute of Chicago show. Because they were hanging in a museum of art, a discussion about their status as art seems entirely fair. If mounted on the walls of a police station, a different discussion might be more appropriate.

Viewed in the pages of On Duty, the need to define them might give way to the strange pleasure of looking at them, however it comes about. The word on these color images, from the accompanying essay by Urs Odermatt, is that the photographer made them to bolster flagging interest in law enforcement as a career among area youth. If the intent was essentially to recruit, then it makes sense that Odermatt tried to make police work look just as good as it possibly could. And it should be said that, in their white belts, hostlers, and Vichy-style hats, these Swiss policemen really do look smart. Or perhaps he really saw police work this way—as almost perfect, with a kind of Swiss-precision romance. Either way, this is a man who, quite earnestly, loved his job.