I. BUNKER KISSERS AND CONCRETE ROMANTICS

The Greenbrier is a luxury resort in the Allegheny Mountains of West Virginia that has been popular for centuries with the southern noblesse; in its earliest incarnation, it dates back to 1778, and its lineage and bearing call certain antebellum associations to mind. (In 1858, on the cusp of the Civil War, a building was raised on the property that was commonly known as the Old White Hotel.) Today, it remains in the resort pantheon. It’s won nearly every conceivable award, from the AAA Five Diamond to the Mobil Four-Star. (It lost its fifth star in 2000, and has since spent tens of millions trying to get it back.)

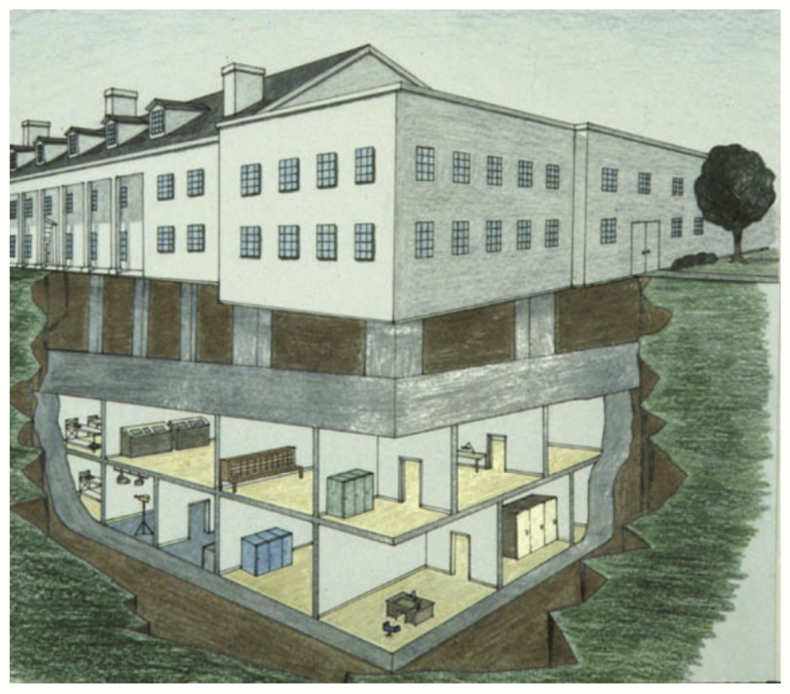

But I hadn’t driven six hours and three hundred miles to check out the hotel’s falconry academy, gun club, or any of its three eighteen-hole golf courses. Since 1995, the Greenbrier has held a more dubious distinction, as a must-see site on the nuclear-tourism circuit. For more than thirty years, from the pinnacle of the cold war era in 1962 until a Washington Post magazine exposé in 1992, there was a top-secret, two-story, 112,000-square-foot fallout shelter beneath the Greenbrier’s West Virginia Wing, intended to house the entire U.S. Congress in the event of a nuclear attack on the capital, known variously as Project X, Project Casper, Project Congo, Project Greek Island, and, simply, the bunker.

A stone-faced guard directed me to a parking spot around back. Stepping into the rain, I realized my tour was about to start, and I didn’t know exactly from where, so I headed down a brick path and stooped into a Lilliputian building filled with tiny furnishings and clothes (called, appropriately, the Doll House) to ask for directions. Then I made my way to the concierge desk to check in, where I was very surprised to be directed, with some solemnity, to surrender any cell phones or cameras for the duration of the tour. Soon a van pulled up outside, and I climbed in with the eighteen other tourers (one urbane young couple and an assortment of older, track-suited others).

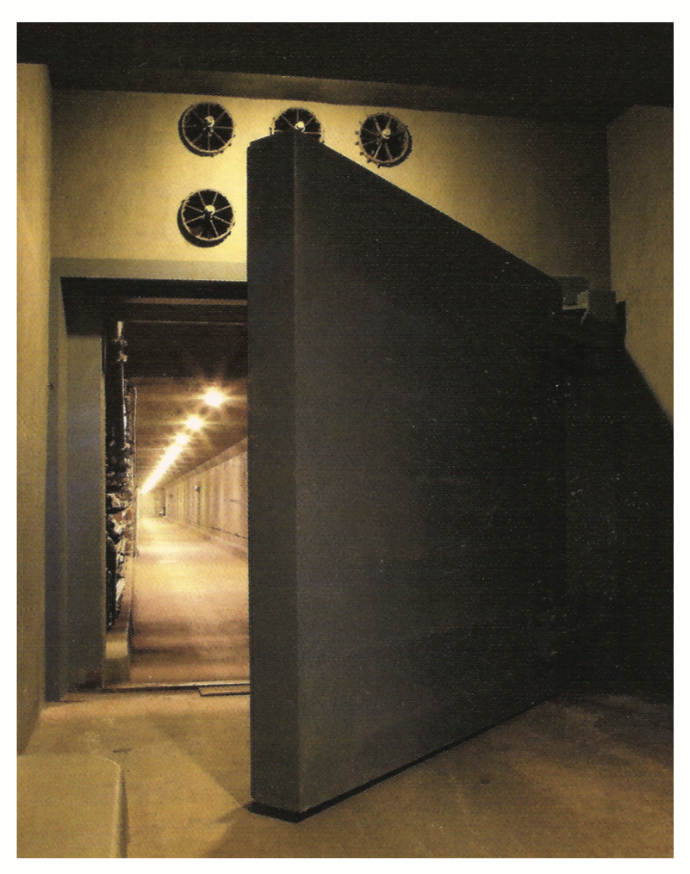

After a short drive, we disembarked and went into the bunker through one of its four blast-door-protected entrances: one walk-in, two vehicular, and one I’ll return to later. This blast door weighed a hefty 25 tons; its hinges were 1,500 pounds each. Our guide, Mia, was a Greenbrier native daughter who’d been leading people through the bunker for ten years—her cabled sweater was embroidered bunker tour guide—and she’d started working at the hotel well before that. As she took us down the long hallway to the decontamination showers, we were greeted with a frowsy, industrial smell and an utter paucity of aesthetic delights. The government, Mia said, had told the bunker architects: “We want no amenities.” It’s not strictly true that they would have had no amenities; if the Congress had actually been entombed for the requisite sixty days, there were lounges where they could have read books or played chess, Scrabble, or bingo. On the second floor, there were two VIP suites for leadership. Their freeze-dried meals would have included chicken à la king. There was also apparently no shortage of prescription meds in the infirmary.

But this shadow world beneath one of the country’s most extravagant hotels bespoke pretty grim postapocalyptic fears. Mia gave us a peek at an incinerator powerful enough to serve as a crematorium, and also told us about the stockpile of weapons the congressmen would have had on hand: twelve-gauge shotguns, .38-caliber pistols, billy clubs. She said she’d asked her former boss why they needed so many weapons to keep the people out. “You know what he said to me? I will never forget it. He said, ‘Well, not just to keep them out, but also to keep them in.’”

For thirty dollars, you get a little more than an hour’s worth of tour, and you end with the exhibit hall, also known as “the Exhibition.” This vast room, which would have been divvied into offices if the bomb had been dropped, was open to the public for the whole thirty-year span of the bunker’s secret existence, thus “hidden in plain sight,” as Mia observed, and serving as a hot spot for pharmaceutical-company conferences, children’s parties, and Monte Carlo nights. Hundreds of thousands passed through during those three decades, and none knew they were standing in a classified government hideout.

To leave the Exhibition, we stepped across a threshold that took us from the bunker into the West Virginia Wing of the Greenbrier, and from a dearth to an overabundance of decor. The WVW carpet could politely be called garish: huge, pale green rhododendron blossoms exploding on a field of darker green. But the wall-to-wall was subdued compared to the wallpaper: white wrought-iron trompe l’oeil bars overlaid on a lemon-frosting-colored background. A hinged screen covered in this wallpaper once obscured the blast door dividing the Greenbrier from the bunker.

Taken together, the whole thing seems like a magical layer cake of feints and secrets. But viewed in another light, the faux-wrought-iron bars are the perfect graphic metaphor for what this portal represents. Mia took us on a tour not only of a cold war–era fallout shelter, but of paradox made manifest: the pretty wallpaper bars that cover an eighteen-ton door; the stripped-down bunker with “no amenities” beneath a resplendent resort; the idea of visiting, as a civilian tourist, a top-secret government site; the whiff of vain, slightly sexual showiness embedded in a moniker like “the Exhibition,”1 and, for that matter, the whole concept of being “hidden in plain sight”; even the simulacral new-oldness of the bunker. (These days, its second floor serves as a secure data-storage facility for Fortune 500 companies, which is why, Mia said, she’d asked us “graciously, and I hope humbly” to relinquish our cell phones; she also told us the bunker had been gutted and completely refurbished during a two-year renovation: every pipe and wire was removed and then replaced with a brand-new replica; as a result, the bunker was now “different, but the same.”)

A powerful aura of mythmaking surrounds this place, the great secret, buried below like a collective unconscious. Mia pointed out at the beginning of our tour that the bunker was a fallout and not a bomb shelter—it couldn’t have sustained a direct hit. It was for that reason that its existence had to be kept a mystery; “its safety was in its secrecy.” And it was for that reason that every element of the bunker had to have a cover story, just like the West Virginia Wing’s blast door had to have a prettily papered cover door. First of all, instead of buying the site outright, the government leased it from CSX Corporation/the Greenbrier to avoid announcing its intentions with public building permits. It also invented a dummy company, Forsythe Associates, to oversee the engineering, and technicians hired to work for the bunker doubled as TV- and phone-repairmen for the hotel. A danger: high voltage sign kept the would-be curious away from the external blast door, and when a landing strip for a supersonic jet was laid down in the tiny, rival town nine miles away, the government relied on rumors—that it was for over-pampered Greenbrier guests—to dispel suspicions. The biggest secret of all was the West Virginia Wing itself, which was built in large part to conceal what was buried beneath it.

I asked Mia how many people had visited the bunker; she said that as of 2005, when it closed for renovations, there’d been 450,000, and she didn’t know how many more had come through since it had reopened for business, in July 2007. A New York Times article from November 2006 claims that when tours first began, “the lines became so long that for awhile [they] had to be limited to Greenbrier guests.”

The Greenbrier, then, is clearly a must-see spot for bunker junkies. The radiation-themed website CONEL-RAD calls it “the Graceland of Atomic Tourism.” But it’s not the only place garnering this kind of interest. In One Nation Underground, indispensable reading for shelter enthusiasts and cultural-history buffs, professor Kenneth D. Rose highlights other stops on the nuclear-tourism trail, including the National Atomic Museum in Albuquerque, where one can “inspect Minuteman and Polaris missiles” and one can “buy silver earring replicas of the ‘Little Boy’ and ‘Fat Man’ atomic bombs” in the gift shop. And he describes the interactive component of the Titan Missile Museum in Green Valley, Arizona: “Visitors are given red folders marked ‘Top Secret,’ as the guide starts the launch countdown in the control room.” (At the Greenbrier, yellow declassified envelopes filled with postcards are handed out at the end, when electronic gear is returned in plastic Baggies.) In June 2008, husband-and-wife duo Nathan Hodge and Sharon Weinberger, both defense reporters, published A Nuclear Family Vacation, which chronicled their extensive “atomic road trip.”

This nuclear-tourism trend isn’t just endemic to the U.S. The Washington Post reported in April 2007 that “the Berlin Underworlds Association, a nonprofit group founded ten years ago, is expected to guide more than 100,000 visitors on special underground tours.” And although it took a while for officials to warm to the idea—“They called us ‘bunker kissers’ and ‘concrete romantics,’” said Dietmar Arnold, the association’s cofounder—now the folks at city hall have had a change of heart. As well they might. Visitors have included Angelina Jolie and Brad Pitt, as well as German president Horst Köhler.

The patina of kitschy innocuousness now attached to almost everything from the ’50s and early ’60s might help explain, too, a recent surge in eBay sales of old fallout shelters. British newspaper the Daily Post recounted in 2003 that several Royal Observer Corps bunkers had been auctioned off to private buyers, and listed some uses of decommissioned shelters: a recording studio,2 home for an Internet server, and a nightclub. The Wall Street Journal recently described a former bomb shelter in Shanghai that has been put to incongruous use as a shooting club, where “hobby enthusiasts… can have a drink and fire a variety of weapons.”

In February 2007, the L.A. Times ran a story called “A Cold War Catalog,” cheekily claiming, “The Cold War didn’t disappear—it just went on sale.” It lists pieces of atomic bric-a-brac, like fallout-shelter signs and Geiger counters, and explains where and for how much they can be bought. The Washington Times has described these kinds of goods as “consummate boomer collectibles.” And according to Kenneth Rose, “a clear indication that the fallout shelter has become a relic of the past [is that] a complete home shelter is on permanent display at the National Museum of American History in Washington, D.C.… The fallout shelter, like other Cold War artifacts, now seems quaint, even amusing.”

But as I climbed back into my pickup after the tour, and managed, finally, after the fourth try, to find my way in the fog (I started to feel like the Greenbrier was actually the Hotel California, and Mia’s words—“not just to keep them out, but also to keep them in”—haunted me in a new way), I began to wonder: how much of a “relic from the past” are fallout shelters, really?3

II. THE BOMB (SHELTER) BOOM

Cormac McCarthy’s 2006 novel, The Road, makes crucial use of a bunker. When it seems the father and his son, refugees in a postapocalyptic world (set in what is either the nearish present or an unspecified future time), are finally on death’s door, the father stumbles on an underground Eden: a fully stocked fallout shelter. Some twenty pages are devoted to the few days the two spend there, where they’re revived. The serendipity of the discovery seems improbable, and yet I couldn’t shake my belief in its authenticity.

And I began, for the first time, to think about fallout shelters. Do they still exist? How many are out there? Who built them? Where are they? And this led to more metaphysical questions: Why would anyone build a fallout shelter? What kind of shelter can it really provide?

Pretty soon, I started finding bunkers everywhere: in John Cheever stories like “The Brigadier and the Golf Widow”; in novels like Barbara Gowdy’s Falling Angels; in Six Feet Under and Mad Men; in plays like 2006’s After the End, in which a mean geek lures his love interest to a London bunker during the apocalypse, then makes her play Dungeons & Dragons and limits her food supply; on websites like Apartment Therapy; and in songs like “Armageddon” by CocoRosie, folk-rock crooner Ray LaMontagne’s “Till the Sun Turns Black,” and the catchy “Eve of Destruction” by Bishop Allen, which, significantly, borrows its title from the famous P. F. Sloan protest song of 19644—and which is also featured in the 2005 film Buried in the Backyard, “a documentary about bomb shelters and the people who build them.” And so on.5

There may be nothing new going on here: since the start of the cold war, the fallout shelter, with its lurid end-of-times associations, has proved verdant fodder for artistic expression. Kenneth Rose devotes an entire chapter to the literary genre of “The Nuclear Apocalyptic” in One Nation Underground.6 And even in our pre-9/11 recent past, the bunker never seemed to stray far from the center of pop-cultural consciousness; in 1999, Christopher Walken and Brendan Fraser starred in the comedy Blast from the Past, about a family that descends into its shelter for thirty-odd years (and the hilarious high jinks that ensue when they emerge).

But this recidivistic obsession with all things fallout shelter hardly lives on in the arts alone. In March 2003, when the Iraq War began, the Wall Street Journal published some relatively astounding findings in the article “A War Room at Home”:

Bomb shelters, of course, were an icon of the ’50s, though their use was actually pretty limited. Even in the height of the duck-and-cover days, fewer than 1 percent of Americans put one in, because many could cost as much as $2,500, or about half the average salary at the time. But in the ’90s, a new generation of shelters with high-tech features spawned an entire $1 billion-a-year business.… Experts say almost 300,000 people have them now, more than during the Cold War era.

Why were so few shelters built in the ’50s and ’60s? While it’s nearly impossible to determine the exact number with any accuracy, then or now, due to a variety of factors mostly pertaining to builder paranoia (many installed their shelters secretly, sometimes at night, and reported them to city building officials as wine cellars, music rooms,7 and so on), Kenneth Rose puts the number as low as 1,565 in thirty-five states by March 1960. Things were kicked into higher gear when President Kennedy urged Americans in a July 1961 speech to build fallout shelters for their families.8 The concomitant Berlin crisis, which led to the construction of the wall starting that August, only hastened along the ’61 bomb-shelter boom. And then there was the Cuban Missile Crisis the following year. Rose claims that “by 1965, as many as 200,000 [shelters] may have been in place.”

But the point of greatest note in the WSJ piece is that there are more bunkers now than there were during the cold war. And the article was describing a trend that started before 9/11. Also in March 2003, the New York Times reported a 40 percent rise in sales of air-purifying systems made by Radius Engineering. “For $30,000 to $130,000, we can modernize any building’s fallout shelter to meet a standard for survival from twenty-first-century warfare,” said the company’s president. (That’s just to upgrade.) And in September 2007, the Associated Press ran a piece on one of the weirdest underreported stories of that year: the town of Huntsville, Alabama, used a $70,000 grant from Homeland Security to reopen its cold war bunkers, and to create “the United States’ most ambitious fallout-shelter plan, featuring an abandoned mine big enough for 20,000 people to take cover underground.”9

In October of 2007, Boing Boing Gadgets published an interview with bunker builder Leonard Henrikson of American Safe Room, “How Much Bunker Could Tom Cruise Get for $10 Million?,” in response to widespread rumors that Cruise was installing a big one under his Telluride estate. The comment thread the piece generated was long and heated, and one poster, “JC REFUGE,” who claimed to be affiliated with Safecastle, LLC, wrote on October 12, “FYI, right now, we are doing more fallout shelter business than ever—you can reach your own conclusion about why that might be.… Bottom line here is that there are lots of folks out there with shelters.”

Turning our attention, then, to “why that might be”: Russia, China, India, Pakistan, North Korea,10 Iran,11 and, possibly, Syria,12 just to name a few reasons. The Seventh Decade: The New Shape of Nuclear Danger by Jonathan Schell (2007) opens: “After the end of the Cold War, the world’s nuclear arsenals seemed to have been tamed to a certain extent, but now they are growling and baring their teeth again. Indeed, the bomb is staging a revival.” And in a New York Times op-ed published in June 2007, defense experts William J. Perry, Ashton B. Carter, and Michael M. May also made the case that we’re facing down a very real nuclear threat:

The probability of a nuclear weapon one day going off in an American city cannot be calculated, but it is larger than it was five years ago. Potential sources of bombs or fissile materials to make them have proliferated in North Korea and Iran. Russia’s arsenal remains incompletely secured 15 years after the end of the Soviet Union. And Pakistan’s nuclear technology, already put on the market once by Abdul Qadeer Khan,13 could go to terrorists if the [then] president, Gen. Perez Musharraf, cannot control radicals in that country. In the same period, terrorism has surged into a mass global movement and seems to gather strength daily….

Things have only gotten worse since this editorial was published, certainly in Pakistan and Iran, and also, arguably, in Russia.

In their piece, Perry, Carter, and May issue a pretty straightforwardly prescriptive road map outlining how we should plan for “the day after.” They don’t advocate the construction of fallout shelters, necessarily—the furthest they go is to suggest that “those downwind and more than a few miles from ground zero… shelter in a basement for three days or so”—but one couldn’t blame the prudent citizen who, having read their article, got out his proverbial yellow pages and started thumbing through for the nearest safe-room manufacturer. (A short list of U.S. companies willing to capitalize on our nuclear-fallout fears: American Bomb Shelter, American Saferoom Door, FamilySAFE, Hardened Structures, Radius Engineering, Safecastle, Utah Shelter Systems, and Zytech Engineering.)

And those are only the threats from outside. For his show Weird Weekends, Louis Theroux (son of novelist Paul) did a special on survivalists in May 2007 in which he interviewed a host of (almost unilaterally charming) “patriots” and other hunkerers-down, and discovered that many harbor virulent fears of the dangers from within, too: our government; “the coming civil war in America”; the New World Order, and so on. If you’re Tom Cruise, you can’t take the threat from outer space lightly, either: as a Scientologist, Cruise “is said to believe evil intergalactic ruler Xenu will attack Earth and so has designed a place to hide underneath his Colorado mansion.”14

So the question isn’t really why build a bunker, but rather, what the hell is wrong with those of us who haven’t yet dialed Safecastle at 1-877-673-2394 (UR-SO-READY-4)?

And, while you’re at it, why not put in orders for a couple? Before the real-estate bubble burst, some aspirationalists skipped over the second-home fantasy and moved on directly to halcyon second-shelter dreams. The Buried in the Backyard filmmakers interviewed several people who had at least one backup bunker. Andre (no last name), in the Berkshires, for example, not only has a superdeluxe safe haven tricked out with guns, smoke bombs, and some sort of system for electrifying the metal, bulletproof shutters on the outside of his building with twenty thousand volts (“If somebody touches those—well, that’s the last thing they’ll do”), he has two other bunkers. One is a tiny hidey-hole built in case his house falls on his megabunker, and the other, which is topped with a fountain replete with naked nymphettes, also serves as a shrine to his dead wife, whose ashes rest in an urn mounted on the wall in one corner.

The popularity of bunkers has been on the rise in Britain, too, but pervasive ambivalence about safe rooms there has led to somewhat logy construction.15 Not so in Singapore, where there’s a mandate that all homes built since 1998 have housing shelters. Safe rooms are also a government-required feature of Israeli homes, although there’s apparently no such stipulation in neighboring Lebanon.16 And in Switzerland, preparations have been even more intense: by 2001, the country had so many bunkers that a Wall Street Journal editorial stated, “Switzerland has pretty much achieved its goal of a bomb-shelter spot for each of its seven million citizens,” and some communities have even achieved “shelter overflow, with more shelter spaces than residents.” According to a 1981 Economist article, “The Swedes think likewise. So do the Finns17 and the Norwegians (not to mention the Chinese and Russians). Three out of four Swedes are already sheltered.” Even Canadians have capitulated to the trend. Ark Two, a bunker made of forty-two school buses is, according to its master architect, retired computer-science teacher Bruce Beach, “the largest privately constructed nuclear fallout shelter in the world,” with space for four hundred inhabitants—including anyone who wants to pay in before the apocalypse. And those pragmatic Germans have apparently figured out a way to make shelters that will protect us from every disaster.

Why have Americans historically had a much more ambivalent, contradictory, and embattled relationship with our shelters than residents of other countries have had with theirs? Here’s the first paradox: even while the irony-loving part of our brains lights up over nuclear tourism and “consummate boomer collectibles,” we’re nevertheless tunneling belowground with as much deadly earnestness and fear as ever.

III. MANIFEST PARADOXY: IN THIRTEEN PARTS

Not only is our relationship to fallout shelters paradoxical; paradox is often made manifest in the architecture of shelters, like in the Greenbrier. Nuclear war is the biggest paradox of all, stemming as it does from a monumental “split,” the splitting of the atom—and, along with it, our psyches. (According to Henriksen, “In the aftermath of Hiroshima… Time magazine espied ‘a new age in which all thoughts and things were split.’”) What does this rivenness mean for Americans?

Friedrich Nietzsche is the king of paradox, and he may be relevant to this discussion. Had Nietzsche been alive during the cold war, he probably would have been an A-1 fan of fallout shelters and a major proponent of civil defense; I can easily picture him in the role of adviser to Herman Kahn—military strategist extraordinaire, RAND Corp. employee, bomb-shelter guru, and inspiration for the infamous Dr. Strangelove18—or even to President Kennedy. Consider a few germane and prescient phrases from Beyond Good and Evil. Nietzsche addresses himself to “we Europeans of the day after tomorrow,” while also espousing the theory that “nothing lasts past tomorrow.” He speaks fondly of “great suffering” and “the great destruction.” He begins Aphorism 193 with “Quidquid luce fuit, tenebris agit,” or, “What has taken place in the light continues in the dark.” He avers that his new philosophers “will teach humans that their future is their will, that the future depends on their human will.”19 And he proclaims, famously: “Life simply is the will to power.”

Let’s compare Nietzsche’s words with some of those circulating during the great civil-defense debate of the early 1960s. President Kennedy, in an open letter to the American public in the September 15, 1961, issue of Life magazine, wrote: “The ability to survive coupled with the will to do so are essential to our country” (italics added). Also in the pages of Life, four years earlier, civil-defense expert and research engineer William Bascom said, a bit sarcastically, “War is a eugenic process which eliminates those without a special will to live.” Or how about Newsweek’s skeptical reaction to Herman Kahn’s defense of civil defense: “Kahn suggests that survivors will ‘put something together,’ perhaps in Vermont. But for the husband who has lost his family or the wife without her children, [the] task of re-creation may require a supreme act of will.” It would seem, then, that these voices of cold war–inflamed America were more or less in harmony with Nietzsche’s. Whether they’re calling it the will to live, the will to survive, or the will to power, everyone is pretty happy to concede that “the future depends on… human will.” This will-to accord is a useful jumping-off point for a discussion of the fallout shelter as paradox. (“Will to survive” is itself sort of a paradoxical idea. How relevant is zest for life really in the face of a twenty-five-megaton bomb? Or metastasized cancer, for that matter?20 Or a genocidal mob?)

So here then are thirteen paradoxes about bunkers:

1.

The prevailing logic of the bunker goes: to survive, you have to be willing to live with the dead, to simulate your own burial. “If there are enough shovels to go around, everybody’s going to make it.” So said Thomas K. Jones, Reagan’s Deputy Under Secretary of Defense.

2.

Bomb shelters mimic bomb attacks. Both are secret, frightening, dark, deadly, or death-like.

3.

The phrase that’s come to be synonymous with nuclear war and its aftermath—“the unthinkable”—is a paradox: a definite article followed by an abstract impossibility.

To put it another way, “the notion of the sublime is continuous with the notion of nuclear holocaust: to think the sublime would be to think the unthinkable and to exist in one’s own nonexistence.”21

4.

The concept of “deterrence”—i.e., the positive-feedback-loop of the arms race and trading threats of mutual annihilation as a way to prevent mutual annihilation—is also paradoxical. The arguments for deterrence, used in service to apologies for bunker building, were the same arguments for bunkers’ futility: “On one hand, the hydrogen bomb made civil defense seem even more urgent and necessary, and on the other, it made any defense seem inadequate and any chance of survival negligible” (Henriksen). In nuclear war, do the ends justify the means? Well, the means are the ends. The end.

5.

The first person interviewed in Buried in the Backyard is a practical-looking middle-aged white woman. As she responds to the directors’ prompt, her family blithely makes flapjacks in the family bunker behind her. She says: “I could survive a year in my house without ever leaving the door.… I do consider myself a survivalist, and I think everyone should be a survivalist. We should want to survive. Our lives are the greatest gifts we’ve ever been given. We should be looking all the time at doing things that will protect ourselves, being alert to threat, and surviving in any aspect, whether it’s economic22 or physical—any aspect, we should be looking at that as a way of life.” The most striking thing about this homily, I think, is its message of “survivalism… as a way of life.” I can’t tell if that’s a tautology or a paradox. Or both.23

6.

Michael Chabon notes in an essay on Cormac McCarthy’s The Road in the New York Review of Books that McCarthy “is ensnared in his hell undone by the paradox that lies at the heart of every story of apocalypse.… To annihilate the world in prose one must simultaneously write it into being.” He also points out several paradoxes inherent to the story itself; for instance, that the father and son are “carrying the fire24 through a world destroyed by fire”; that in this world “the idea of hope itself comes to seem like a kind of doom”; and that the son “leads an all but storyless existence in which meaning, motivation, and resolution have no place and nothing to do. And yet of course the only way McCarthy has of laying this tragic state before us is through storytelling.”

7.

The purpose of the fallout shelter is to prevent physical harm, to ensure that its occupants survive to live another day (and spread their “way of life”). But—disregarding for a moment the question of whether or not anyone would really want to survive a nuclear winter—let’s skip right to whether or not they could, will or no will. This question is contentious, to say the least, and scientists lined up on both sides of the divide from the moment it became a question. Plenty, like our Strangelovian friend Herman Kahn, were happy to throw down bets on bunkers’ life- and thus nation-saving potential. In On Thermonuclear War, Kahn writes with almost giddy enthusiasm: “If… by spending a few billion dollars, or by being more competent or lucky, we can cut the number of dead from 40 to 20 million, we have done something vastly worth doing!” He even includes a table (“Tragic but Distinguishable Postwar States”) in which he predicts how long it would take, in years, for the country to recover economically from a nuclear blast based on the number of dead. (For instance, 2 million dead would take one year, whereas 160 million would take about one hundred years.) Many experts, both then and now, agree that fallout shelters (when used correctly every time) can save lives.

But who’s speaking for the opposition? Here’s one cheerful assessment from a January 1962 issue of Science News Letter: “Buying a fallout shelter is like betting on a horse race. The odds on survival, at best, are poor.” The identities of other skeptics are surprising. Val Peterson, Federal Civil Defense Administration chief under Eisenhower, for example, was deeply cynical about the usefulness of trying to plan for life after nuclear war. Such a life, Peterson said, “is going to be stark, elemental, brutal, filthy, and miserable.… We are just not going to be prepared for that kind of hell.” Even a pamphlet released by the Office of Civil Defense in late 1961, Fallout Protection: What to Know and Do about Nuclear Attack, seems to offer ambivalent views on the survivability of said nuclear attack: “Predicting that nuclear war would be ‘terrible beyond imagination and description,’ the authors then… seemed to argue the contrary: ‘If effective precautions have been taken in advance, it need not be a time of despair’” (Rose).

Shelters also can’t protect against the firestorms some physicists thought could erupt after a thermonuclear attack.25 We first became keyed in to firestorms in 1943 during an incendiary bombing raid on Hamburg, Germany (code name: Gomorrah), in which fires reached 1400˚ Fahrenheit. Rose reports that “many of those who took to their shelters during the Hamburg raid died from heat stroke, dehydration, and carbon monoxide poisoning as the storm sucked all oxygen out of the air.” Lots melted into “‘a thick, greasy black mass,’ or ‘left behind… Bombenbrandschrumpfleichen (incendiary-bomb-shrunken bodies).’”

Hanging out in a shelter for a protracted period could also be deleterious to one’s health. Studies conducted during the cold war, including one on naval officers, showed that physical side effects of shelter living might include: flatulence, constipation, and weight loss; elevated body temperature, headaches, lightheadedness or “actual dizziness,” diarrhea, nausea, allergies, and the common cold. Given the poor-at-best odds of surviving a nuclear attack in a bunker, it’s hard not to wonder if they might actually be bad for your health.

8.

The bunker’s ancillary purpose is to protect the psyche. Sharon Packer, executive director of the American Civil Defense Association and a vice president of Utah Shelter Systems, said in an interview for Buried in the Backyard: “I sleep real well at night. And I think the test is that I’m happy, not living in fear.” (Packer, who built her first bunker at age eight, seems most concerned these days about an electromagnetic pulse attack, or EMP, which could be produced by “even a small nuclear bomb detonated at high altitudes,” and which would wipe out the U.S. electrical system in less than a second. She thinks this could kill 150 million Americans within six months, and she sleeps with an EMP alarm in her bedroom.)

So what of this notion that shelters afford psychic inuring against the dangers of nuclear calamity? That, for mental security, we have to mimic physical security? A whole smattering of psychological studies conducted during the ’60s (psychologists were extremely interested in the fallout-shelter debate) reveal, paradoxically, that owning a shelter didn’t really make people feel safer or less anxious. To the contrary: One report published in Public Opinion Quarterly was based on data collected during a survey of eighty shelter owners in northern New Jersey in early 1962. The researchers made a few fascinating discoveries: Shelter-owners and non-shelter-owners were “remarkably alike in their perceptions of the threats posed by the U.S.S.R. and the hazards of nuclear war”; “the two groups revealed approximately the same level of knowledge about the causes and effects of radiation from fallout”; and, most interestingly, “the nonshelter people had a less pessimistic view of the future and were less inclined to view the world as a ‘chancy’ place than the shelter owners.” Researchers determined that “the two sets of people view the future quite differently. The nonshelter people appeared to be more hopeful.”

And what about the argument made in Science News Letter in 1963 that “America’s fallout shelter program may be damaging the mental health of our children”? It relates that some “psychologists studying the effects of shelter building and school shelter drills have… conclud[ed] that the net result of these efforts may be a serious increase in anxiety.” A Dr. Isidore Ziferstein quoted in the piece observes that “many children… dream of bombs dropping on them” and with amazing prescience, he speculates that children who have doubts about the efficacy of adult-mandated duck-and-cover drills “start questioning the figures of authority who have recommended this dubious salvation. The result is a loss of confidence which could lead to insecurity feelings and rebellious, delinquent behavior” (which is of course exactly what happened in the late ’60s). The piece stated that, pre-Heathers-era suicide-pact awareness, “two teenage best friends made plans for dying together in the same school shelter,”26 giving new meaning to the concept of the “sheltered child.”

An even more amazing study made a case for “resignation” and “rational inaction,” wondering, “given… lack of protection [from nuclear attack], is it any less rational than other courses of behavior for [a] person to do nothing?” The study quotes psychiatrist Sanford Gifford in what seems like a passivity paradox: “We may believe simultaneously that no nation would dare to begin nuclear war and that if war occurred by accident, life would no longer be worth living. From either direction we reach the same conclusion, that nothing can be done, thus justifying a fatalistic passivity that is strangely comforting rather than alarming.” The authors conclude, “This paper suggests that there might be circumstances under which resignation would not be pathological but could be considered a type of rational behavior.”27

Let’s not forget, too, what the psychological effects of actually staying in a shelter might be. The same gassy, constipated naval officers mentioned above also became “moody” and “angry or withdrawn” during a four-and-a-half-day sequestration. “The steroid levels in their urine rose… possibly due to ‘mild emotional stress,’” according to the Washington Post. Rose writes about a family who, during a similar experiment, experienced boredom, infighting, and “a depressive bleakness and diminution of vitality.” (In the weeks after, the father got into two separate car accidents.) And in the 1965 informational pamphlet Living and Nursing in a Fallout Shelter, the author notes that, during a simulated shelter stay, a “person taking a special course for shelter management instructors suffered a serious mental disturbance, went berserk during the period of confinement, and was immediately hospitalized.”

9.

There’s something a little libidinous—even incestuous—about a fallout shelter. Another paradox of shelter living is that the people one ends up protecting in a private bunker are those with whom one could never propagate future members of the species, leaving to die all the strangers we might copulate with.28

10.

In the early ’60s, the build-or-don’t question was explosively contentious; everyone from politicians to scientists to civilians to journalists to theologians had an opinion.

The great gun-thy-neighbor debate was the primary reason the theologians weighed in. Those considering the practical implications of a private bunker soon realized they’d have to confront what they’d be willing to do when the less-well-prepared tried to storm their shelter gates. Specifically, could they shoot to kill their friends and non-nuclear family? The answer, for some, was yes. During a civil-defense meeting of local residents in Hartford, Connecticut, a young mother asked her shelter-owning neighbor (and closest friend of ten years) if he’d let her and her baby into his bunker if she were caught outside in a nuclear attack. He said no. She pressed the issue, and asked what he’d do if she wouldn’t leave. Finally, Rose writes, “he said that if the only way he could keep his friend out would be by shooting her and her baby, he would have to do it.”29

Maybe even more disturbing, some theologians thought this was acceptable behavior. In an article published in September 1961 in the Jesuit magazine America, Father L. C. McHugh, S.J., contended that “a man under grave attack may take those emergency measures which will effectively terminate the assault, even if they include the death of the assailant” and added that those with shelters ought to “think twice before you rashly give your family shelter space to friends and neighbors”; he even implied that having a revolver in one’s survival kit wouldn’t be such a bad idea.

Loads of religious leaders took issue with this cavalier stance, but McHugh’s comments illuminate one of the essential American paradoxes that came out of the shelter debate: can a country that has since its founding seen itself as a great Christian nation, a “city upon a hill,” in John Winthrop’s famous words, and a shining example to the rest of the world, can that country’s citizens, in good conscience, casually promote the abdication of its dearest Christian values for the more expedient aim of self-preservation? Maybe it’s counterintuitive, given our guiding myths, but independence and self-sufficiency aren’t really all that Christian.30 As Berkeley philosophy professor Hubert Dreyfus has argued:

Being self-sufficient is a great thing for the Greeks…. All heroes are self-sufficient. And, generally, the alternative to being self-sufficient is to be slavishly dependent on somebody or something. But of course from a Christian point of view… being self-sufficient is a very, very bad thing. Pride is the thing that the people at the bottom of the inferno, in Dante, who are self-sufficient [suffer from]. Who are so detached and cold-blooded that they’re literally frozen in ice. And who… are so self-sufficient that they’re ready to betray anybody just to be self-sufficient.… The worst are the people who are totally selfish and totally self-sufficient and thereby betraying type of people.

Yet another paradox emerges from all this fallout fallout: the fact that bunkers were so controversial during the ’50s and ’60s, and especially because of the gun-thy-neighbor issue, explodes the myth of American individualism over and above communalism. Even during the bomb shelter boom of 1961, less than half of 1 percent of the population installed private shelters, partly because they were so expensive.31 But according to Rose, it was largely because people cared more about their communities, their neighbors, and the preservation of morals than they did about the preservation of their own lives.32 Which, ironically, brought them a little closer to the theoretical values of their enemy no. 1 than to their own espoused truths, which they’d die, they thought, to defend.33 They weren’t willing to go from being a city on a hill to a city underground; from being a utopia to a “subtopia.” As the Yale Review put it at the time: “What would John Winthrop have thought?… It is difficult to construct a Heavenly City, when the contractor’s plans, of necessity, allot a space for Hell.”

11.

One reason we need nukes, for both their destructive and creative potential, is because we’re running out of oil. As we engage in more wars over fewer resources, we’ll need to keep stockpiling weapons of all kinds. And as the last reservoirs of our petroleum supplies dry up, probably within decades and not centuries, we’ll also need new and more efficient ways to power our lives. Thus the nuclear paradox: its energy is both good and evil—or, as Nietzsche might have put it, it’s beyond good and evil.

12.

And what about our biggest American paradox? The one that’s defined us since Word War II, when all this nuclear flimflam began? For some reason, we think waste begets prosperity; that economic fecundity depends upon “accelerated obsolescence.” The architect George Nelson wondered back in the ’50s how the U.S. could be so rich and so wasteful at the same time. His answer was that America was so rich precisely because of its wastefulness, which facilitated mass production.

But can we continue turning nothing into something forever? Between the financial crisis and the imminent end of our natural resources, we’re starting to see that the answer is no. Fallout shelters represent one manifestation of our wasteful, consumerist impulses—at the same time that they refer to something (nuclear holocaust) that suggests an absence of future opportunities for consumption.

13.

By building bunkers, we’re reacting to a perceived menace (international terror cells, “dirty” bombs, al Qaeda, “those people” who “hate us” and our way of life, etc., etc.) instead of to the very real and impending danger of what our wastefulness has wrought: global warming, climate change, super-storms, and the end of our “way of life” as we’ve known it.

IV. WASTE NOT, WANT NOT

As a New Yorker, I spend a lot of time underground, in the subway. All that time has afforded me ample opportunity to consider why Americans’ relationship to the fallout shelter is especially fraught. I don’t think it’s just because our bunkers, unlike those in some other countries, are most often buried—subways don’t seem to pose the same kinds of metaphorical problems for people that shelters do—although it’s true that the furtiveness potential of a belowground safe-haven (it can be built in secret, and kept a secret) necessarily influences how we think about them. It’s also true that it’s easier for Americans to build belowground bunkers, because many of us own private homes; apartment-dwellers, renters, etc. (i.e., most of the rest of the world), don’t have that luxury. It may be that safe rooms in Israel and housing shelters in Singapore harbor none of the associations of subterfuge that the American bunker has, because they’re neither buried nor secret (and maybe also because they’re government sanctioned).

But I think there are other reasons we feel so ambivalent about our bunkers. While we can acknowledge now that “there are people who genuinely hate us, who have the ability to come over and do things that can totally disrupt our infrastructure, disrupt our economy, as well as the lives of many, many people,”34 we don’t necessarily want to admit “betrayal of America’s errand to the world,” as Rose puts it.

Also, as we’ve seen, bunkers are physical reminders of some of the deepest contradictions in our cultural mythology; they both represent everything we stand for—scrappy individualism, independence, survivalism—and conflict with our most cherished principles—Christian values, selflessness, communalism. We have a peculiar inability to reconcile our notions of the individual’s role within the collective, the relative significance of the public versus the private sphere. Our relationship to bunkers is paradoxical because we are paradoxical.

But our ambivalence, too, stems from the fact that today we find the threats to our security (both national and personal) confusing. On the one hand, the external threat seems more unnervingly diffuse and un-pin-down-able than the monolithic Soviet menace was. Then, it was intelligible; even if the threat itself was “unthinkable,” the enemy was knowable, ideologically based, geo-historically situated, imaginable, comprehensible. The cold war was a war: the enemy was circumscribed and defined. That’s not so true these days. On the other hand, our sense of internal threat has also grown. We have a conflicted relationship with our government; we don’t generally live in fear of it like the denizens of many developing countries, but we also don’t totally trust it. So we don’t really know who our enemies are anymore. Bin Laden? Putin? Al Qaeda? So-called terror cells? Our government? Our neighbors? Who? Utah Shelter Systems’ Sharon Packer puts it best. Referring to those who might try to get into her bunker after an attack, she has said: “The people themselves become a threat in an actual disaster.” In that scenario, it’s us—anyone without a bunker—who have become the real enemies.

And, actually, that’s about right. We are our own worst enemies, but not because we’ll be ready to shoot each other’s babies to protect our shelter doors. We’ve been damned by just the kind of wastefulness that’s encouraged some of us to buy and build and stock shelters for more than fifty years. Michael Chabon concludes his review of The Road by describing the ways in which it plays upon a parent’s greatest fears: “Above all,” he writes, it’s “the fear of knowing… that you have left your children a world more damaged, more poisoned, more base and violent and cheerless and toxic, more doomed, than the one you inherited.”

In 2006, the New York Times reported a curious cold war artifact that had turned up inside the Brooklyn Bridge: 352,000 Civil Defense All-Purpose Survival Crackers. These crackers were apparently still edible, but in most civil-defense shelters elsewhere, “the crackers got moldy a very long time ago.” Over the years, city workers nationwide have also uncovered or repossessed millions of dollars’ worth of drugs like phenobarbital and penicillin, and, in 1984 in Cambridge, Massachusetts, the city’s Emergency Management director discovered two and a half tons of pineapple sour balls that had been stored since the ’50s, along with “tons of supplies, unused medical kits, even a small portable hospital.”

The sour balls and crackers were reused (the former donated to nursing homes and, for some reason, fire departments, and the latter sold as hog feed), but most public and private shelter-relics from the ’60s are just reminders of colossal waste: Santa Ana, California, is home to a former shelter, Building 16, which is most likely soon to be torn down, according to the Orange County Register, “since a rehab would involve hazardous material removal and the complete replacement of its electrical, air conditioning and other systems,” and in Rockville, Maryland, the basement classrooms built as part of a school shelter system have been locked up. “There’s no power down there,” the Washington Post reported, “and asbestos is in the ceiling tiles.” The Roanoke Times noted that “the federal government stopped stocking public shelters in 1971, and the food was removed in 1978 because much of it was no longer fit to eat.” As the Boston Globe put it, “by the time the Cold War ended in 1989, the billions of dollars that taxpayers had spent preparing for nuclear war seemed good for one thing: a few good yuks.”

The period from the second half of the twentieth century through today has been the most wasteful in history, especially in the U.S. We’ve been using up our resources at record speeds instead of trying to renew them. Dr. Roger Revelle, the mentor Al Gore mentions in An Inconvenient Truth, started making disturbing discoveries about climate change as early as 1957. If the billions spent on civil-defense efforts from the ’50s through the ’80s had instead been redirected toward cutting emissions and oil dependency, maybe we wouldn’t now be facing the very real threat of global warming and its attendant natural calamities. We can’t give our predecessors too much of a hard time, though; they thought the whole planet would be obliterated tomorrow—they weren’t aware of or worried about what might happen the day after tomorrow. And we also could’ve done a lot to slow the damage starting even a decade ago, when we already knew what was happening.

Some have tried to do their part, repurposing old bunkers instead of letting them rot. One couple in Chris Smith’s 2001 film Home Movie turned an old missile silo into a sort of hippie palace, host of happy drum circles and replete with a purple lava lamp, a poster proclaiming “Love everyone unconditionally,” and side-by-side toilets. The two talk about transforming the “quite heavy” energy of the place. They also discuss throwing tornado parties (they’re west of Topeka, Kansas), because there’s no reason to fear them down there. And another family, in Vermont, chose to build a new home belowground not (directly) because of threats of terrorism or even earthquakes, but to cut energy costs. Their home, built by Earth Sheltered Technology in Mankato, Minnesota, also cost them tens of thousands less to build than an aboveground house of the same size. Who knows—maybe some day soon we’ll all be living underground, but for a very different kind of civil-defense reason.

Our civil-defense strategy shouldn’t be stockpiling arms or building bunkers. It should focus on trying to ensure that our planet is habitable in future decades. For around $130,000, what you’re likely to spend on a new bunker (and leaving aside, for now, the cost of stocking the bunker), the average family could buy a 2008 Toyota Prius for about $22,500; “seal” their home’s insulation “envelope” and put in energy-efficient light bulbs for less than $200; install enough solar panels to power an average house (with a small bedroom AC) for about $64,000; put in a gray water recycling system for roughly $7,000; and add smart windows for around $20,000. You’d still have $16,300 left over, without even factoring in the amount you’d save on electricity bills and gasoline. And of course if the government started setting aside some of the billions (out of trillions) that it’s spent in recent years on invading oil-rich countries, and invested those instead in new strategies for stopping our oil addiction and developing greener technologies, we might be able to push beyond paradoxy and rational irrationalism to something more like rational rationalism.