In the distance to the north, we could see an ice floe, perhaps fifty feet long, hovering about thirty feet off the surface of the ocean. It rose up into the air, the ground beneath it perfectly visible, an expert magician’s trick.

This is what’s known as a “superior” or “looming” mirage, when the air below the line of sight is colder than the air above it, giving objects the appearance of floating above the water’s surface. (The opposite is what you see on hot days, when the ground in the distance shimmers.) Superior mirages are a hallmark of polar climates, responsible for the so-called Flying Dutchman, the appearance of a ship that floats above the sea (thought to be a harbinger of impending death); the Novaya Zemlya effect, when the sun appears as a rectangle or an hourglass; and sun dogs, when multiple suns appear on the horizon.

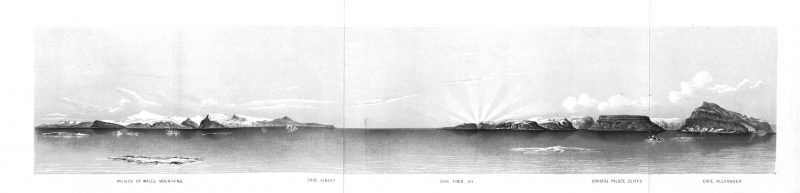

It was late June; the sun had been shining constantly since April, and wouldn’t set until August. Our latitude was roughly 78.5° north, on the northern tip of Spitsbergen, the largest and only inhabited island of the Svalbard archipelago. I had been sailing with a group of other artists, writers, and scientists, up the northwest coast of the island, and we had gone as far up as we’d be traveling. To the north, we saw only a few scattered ice floes, some on the water and some above it. For the most part, the horizon presented an undisturbed and placid sea, stretching endlessly into the curve of the earth. For all you could tell, one could sail north indefinitely, straight toward the North Pole and beyond.

The Svalbard archipelago has been a prime launching point for polar expeditions since the early nineteenth century. Among those who came here seeking the North Pole was John Franklin, a veteran of the Napoleonic Wars, who arrived in 1818—not yet “Sir John Franklin,” not yet the mythical figure he would become. Franklin had sailed with Captain David Buchan to Svalbard, hoping to get beyond it and into the Arctic Ocean. Buchan captained the larger Dorothea, while Franklin, then just a lieutenant, helmed the smaller Trent. North of Svalbard the two ships became trapped in ice; the Dorothea was crippled and could not go forward. Franklin, believing that he had found a way past the pack ice all around them, advocated taking the Trent forward alone, but he was overruled by his commanding officer, and both ships limped home.

This didn’t deter Franklin, any more than did an even more disastrous expedition overland in northern Canada a year later, in which eleven of his twenty-man crew died and which earned him the nickname “the man who ate his boots.” Franklin kept trying to find his way north, and in 1845 he finally got his wish, as the commander of two massive, ice-proven ships—the Erebus and the Terror—with orders to finally push through the ice and discover a northwest route between Europe and Asia over North America.

Franklin and his 128 men didn’t return. They were expected to be gone for two years, possibly three, but by the autumn of the second year Franklin’s wife, Jane, became worried and persuaded the Royal Navy to send out search parties. The search was about more than just a pair of lost ships: British pride hung in the balance. As writer Anthony Brandt tells it, the British “believed it their peculiar destiny to [force the Northwest Passage], to triumph over the ice and add this exclamation point to the great victories of Trafalgar and Waterloo, underlining in the process British command of the world’s oceans.” In the next decade, the search would swell; ultimately over twenty different expeditions would be launched. In the annals of polar exploration, this period would become known simply as “the search for Franklin”: whole new terrains were mapped, lives were lost, massive ships were destroyed and abandoned. With the possible exception of Columbus, no other single individual has come to be associated with such a massive swath of the globe.

As the English became less optimistic about finding Franklin alive, his wife turned to America, and in 1853 explorer Elisha Kent Kane helmed one of several American-led expeditions that had joined the search. By then, Franklin had been gone for eight years. It seemed improbable that such a large expedition could have been gone that long and managed to survive—and yet Kane had faith that Franklin and his men were still alive. He argued that Franklin’s ships might have made their way through the polar maze of drifting, lethal ice, and might have somehow made it through into an open polar sea, where they might now be living near the North Pole itself, in a verdant land stocked with fish, flesh, and fowl.

*

If Kane’s hypothesis seems crazy, he was far from the only one who believed it. Theories about the existence of an open polar sea had circulated for centuries. A now-lost medieval manuscript, the Inventio Fortunata, spoke of a priest and mathematician, Nicholas of Lynn, who supposedly sailed to a water-bound North Pole in 1360. Nicholas’s voyage, in turn, influenced mapmakers for centuries, and his eyewitness account of a polar sea is cited on multiple sixteenth-century maps. Then there was Joseph Moxon, “Hydrographer to the King’s Most Excellent Majesty,” who in 1674 claimed to have met a Dutch seaman who’d sailed to the North Pole and found warm water:

I askt him if they did not meet with a great deal of Ice? He told me No, they saw no Ice. I askt him what Weather they had there? He told me fine warm Weather, such as was at Amsterdam in the Summer time, and as hot. I should have askt him more questions, but that he was ingaged in discourse with his Friend, and I could not in modesty interrupt them longer.

By the nineteenth century, when the era of polar exploration had ramped up in earnest, an open polar sea was a commonly held belief in many quarters, the result of a mix of both inductive and deductive thinking, scientific theory and firsthand (if erroneous) observation. The explorer Ferdinand von Wrangel reached open waters above Siberia in 1820 and believed he had reached an open polar sea: “We beheld,” he wrote, “the wide, immeasurable ocean spread before our gaze, a fearful and magnificent, but to us a melancholy spectacle.” In the early 1830s John Barrow, Second Secretary of the British Admiralty, wrote that there was “every reason to believe that at all times a very large portion of the Polar Sea is entirely free of ice.”

The sixteenth-century Dutch astronomer Petrus Plancius believed this temperate sea was mainly a function of the twenty-four-hour sun: “although his rays are weak, yet on account of the long time they continue, they have sufficient strength to warm the ground, to render it temperate, to accommodate it for the habitation of men, and to produce grass for the nourishment of animals.” But by the nineteenth century, scientists were emphasizing more and more the dynamic nature of the earth itself, and the interrelationship between tides, oceans, currents, and other phenomena. The open polar sea, it was believed, was fed by warm currents from the tropics, just one part of the earth’s complicated circulatory system.

Explorers were well familiar with the herds of musk oxen in northern Canada, but had no clue where they wintered, and assumed they must be migrating to warmer climates somehow: if they weren’t coming south, it was reasonable to conclude they might be going north. Likewise, some mistakenly assumed that certain birds seen in the Arctic, including sandhill cranes, were too heavy to make a long migration south, and must similarly be flying to somewhere warmer, somewhere north. Kane, like so many others, came to believe in the idea of a mild and hospitable North Pole, perhaps like southern Canada, with scores of musk oxen and fat birds for the taking—and where Franklin had sought refuge. Particularly as the years went by and hopes for Franklin’s survival diminished, his fate became intertwined with the belief in the open polar sea. If he had survived, it was due to this heretofore-unproven hypothesis—to keep one hope alive was to keep both hopes alive.

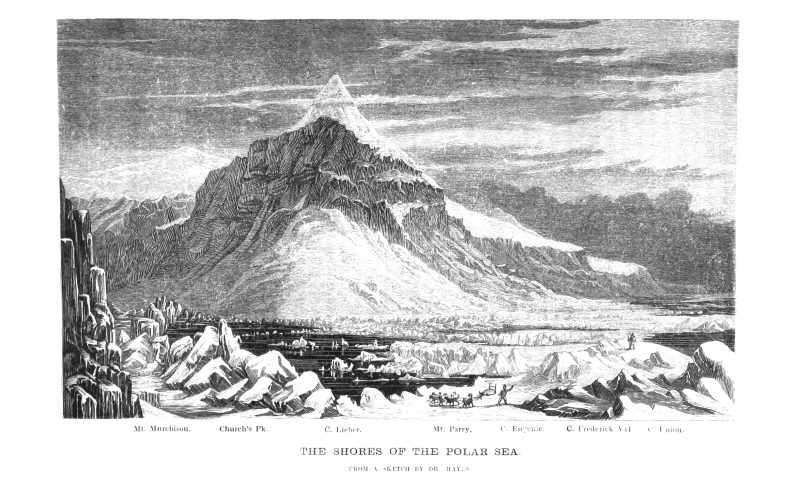

Kane’s expedition was not the utter disaster that Franklin’s was, but it was close. He never found any trace of Franklin, and his ship was icebound off Greenland for two years. Three men died, and finally, in 1855, Kane and his men abandoned the ship to the ice and worked their way down the coast of Greenland in small boats they hauled over the ice. But Kane did claim one success: his expedition had found, finally, the open polar sea. While icebound, he’d sent out a sledge with two of his crew, Hans Hendrik and William Morton. About twenty-five miles past the 81st latitude the two men climbed a five-hundred-foot cliff and looked out onto an unbroken expanse of water, open as far as the eye could see.

On his return home, Kane crowed of his discovery of an “open and iceless area, abounding with life, and presenting every character of an open Polar sea.” Kane, like his supporters, had no reason to doubt Hendrik and Morton’s account—they’d all been expecting to find such a body of water. But while Hendrik and Morton might have found open water, they most certainly had not found an open sea leading to the North Pole itself. Kane’s discovery was cited for the next few years, until 1879, when the Jeannette, an Arctic vessel sent out in search of another missing ship, got caught in pack ice and was crushed by it north of the 77th parallel.

A few years later, in 1892, Fridtjof Nansen decided that rather than beat the ice, he could join it: he designed his ship, the Fram, to withstand its pressures, then sailed north with the hope of getting caught in it. Onboard the Fram, Nansen drifted for two years encased in ice, going farther north than anyone before him had, encountering nothing but endless pack ice. The open patches of sea seen by Kane and von Wrangel were revealed, finally, as what they had always been: hope and limited perspective, delusions and optical illusions.

*

After seeing the Arctic Ocean myself, I have a bit more sympathy for Hendrik and Morton’s account. Off the northern edge of Svalbard, I looked past those few hovering icebergs and saw no sign of any obstacle preventing us from sailing due north to the pole itself. It’s easy to look north from such a place, into the endless distance before you, with no buildings or hills to block your sight and no pollution to dim it, and to believe that nothing stands in your way.

Mariners with experience can look at clouds on the distant horizon and judge from the way the light reflects off their undersides whether the water beneath is liquid (“water sky”) or frozen (“ice blink”). I was in no way experienced enough to read such clues during my travels, but I could read the satellite printout we had of the Arctic Ocean and knew there was heavy pack ice deceptively close, just beyond the limits of my sight. The clarity of vision here is deceptive, the horizon treacherous. Up here, amid the looming mirages and optical tricks, your eyes see whatever you want them to see.

From a twenty-first-century vantage point, it is easy to view the lives and treasure devoted to finding a tropical sea at the poles as a tragic result of stupidity, hubris, and folly; the notion of such a polar sea—with its warm water fed by tropical currents and stocked with countless fish, tree-lined islands overrun with musk oxen unafraid of humans, and skies deluged with slow, fat birds—strikes us as utterly counterintuitive, and speaks to an embarrassing age of embarrassing delusion and arrogance. But before we write it off entirely, it’s worth noting that we now believe plenty of other counterintuitive ideas about the natural world: that the earth is round and revolves around the sun, that matter is made up of tiny atoms, that washing one’s hands between surgeries limits the spread of infections, and so on. At the dawn of the scientific age of the nineteenth century, all sorts of long-held beliefs were being overturned, and all sorts of counterintuitive ideas were turning out to be correct. Those advocating the theory of the open polar sea might have been wrong, but they were not wrong to think such a thing might be true.

Historian Michael F. Robinson argues that it’s premature to dismiss theories of an open polar sea as nothing but pseudoscience. As he notes, it “is a sign of the theory’s strength that the most active debates considered how, not if, the polar sea remained free of ice.” He contends that the theory “is more representative of its age: of the people and institutions that shaped geography, their activities, and processes by which they came to understand the hard-to-reach places of the globe.” Robinson argues that one of the reasons this theory has fallen into such disrepute over the years is precisely because it was taken up by marginal writers and dubious thinkers who fixated on the mystery of the poles and what might be found there—possibly even an entrance to an interior world, a hollow earth.

*

The history of hollow-earth theories parallels neatly the golden age of Arctic discovery. The same year that Franklin and Buchan attempted to get past the ice in Svalbard, Captain John Cleves Symmes, a veteran of the War of 1812, espoused an utterly unique view of the earth’s geography. In 1818 Symmes printed five hundred copies of a circular that began: “I declare the earth is hollow, and habitable within; containing a number of solid concentrick spheres, one within the other, and that it is open at the poles 12 or 16 degrees; I pledge my life in support of this truth, and am ready to explore the hollow, if the world will support and aid me in the undertaking.” His tireless self-promotion on the lecture circuit eventually brought him enough attention to filter into American consciousness: Symmes’s work indirectly influenced Edgar Allan Poe, and appears in Thoreau’s Walden. (“It is not worth the while to go round the world to count the cats in Zanzibar. Yet do this even till you can do better, and you may perhaps find some ‘Symmes’ Hole’ by which to get at the inside at last.”) John Quincy Adams supposedly made plans near the end of his presidency to fund a polar voyage to test Symmes’s ideas.

Franklin’s disappearance provided more fodder for the hollow-earth theory. The Boston Evening Transcript ran an article, in October of 1851, suggesting that the reason Franklin’s expedition hadn’t been found was because it had in fact slipped into Symmes’s hole and was now somewhere inside the earth. Similarly, Salt Lake City’s Deseret News of February 1852 published an account of one Cornelius P. Broadnag, who claimed to have the journal of an American named Jonathan Wilder, which told of an “internal region” inside the earth that Wilder had traveled extensively. Praising Broadnag’s account, the Deseret News’s editor, Dr. Willard Richards, wrote, “Has Sir John Franklin passed in at the North Pole? Is he now exploring the Internal Regions? If so, when will he come back?”

Had Franklin and his men made it into the hollow earth, they might have found, as Wilder claimed, a civilization that knew no writing but that mysteriously spoke Hebrew, populated by descendants of the last inhabitants of Jerusalem after its sacking by Babylon who had been led by an angel into the earth’s interior. In a world without sun, moon, or stars, illuminated only by light spilling in from the great holes in the North and South Poles, the crews of the Terror and the Erebus would have found limitless precious metals and feasted on the meat of a strange mammoth-like animal that these people had domesticated while they waited for the Messiah to return and lead them back to the earth’s surface.

The truth of Franklin’s end, as it was finally revealed, was both more predictable and more shocking than this. In 1854, dishes and other artifacts from the Trent were sold to explorer John Rae by Inuit traders, and five years later an expedition under the command of Francis McClintock used those same traders’ testimony to locate the remnants of Franklin’s men on King William Island. McClintock also found evidence that Franklin’s men had engaged in cannibalism in a last-ditch attempt to stay alive: human bones were cut clean with steel knives, and had been broken open to extract marrow. This last fact became too much for the English public to bear; that their model of imperial chivalry had descended to such barbarism seemed unbelievable, even with incontrovertible evidence. Charles Dickens was among those who preferred to blame the Inuit witnesses rather than face this fact: “We believe every savage to be in his heart covetous, treacherous, and cruel,” he wrote, suggesting that the Inuits had murdered the survivors of the expedition themselves.

*

Contemporary scholars like Robinson, in an attempt to somewhat salvage the reputation of the open polar sea theory—or at least contextualize it within a less-Whiggish history of science—would have us separate it from the more-outlandish theories of the hollow earth. An oceanographer’s claim that the polar sea is temperate, based on unproven theories of thermodynamics, animal migration, and currents, is radically different from a similar claim made by someone like Madame Helena Petrovna Blavatsky, founder of Theosophy, who wrote in her 1888 magnum opus, The Secret Doctrine, that “even in our day, science suspects beyond the Polar seas, at the very circle of the Arctic Pole, the existence of a sea which never freezes and a continent which is ever green.”

Disentangling serious history from its problematic by-products, though, is always a tricky process. For not only did the open polar sea theories lead to pseudoscience, they also led to a strand of wonderfully odd science fiction. Jules Verne’s The Voyages and Adventures of Captain Hatteras, for example, begins with a mysterious voyage north and a megalomaniacal captain attempting to reach the pole for England. The crew’s resident scientist, Dr. Clawbonny, argues early on that just as magnetic north is not coterminous with the geographic pole, so, too, is the coldest spot on the northern hemisphere not the pole itself. Believing that this “pole of Cold” is farther south, around latitude 78° north, Clawbonny predicts that the geographic north pole, a thousand miles northward, will be correspondingly warmer. Sure enough, Hatteras (a poor man’s Ahab, but compelling nonetheless) and his surviving crew eventually reach a temperate polar sea, where icebergs are infrequent and harmless, and where there are thousands of species of unknown birds, fish, and marine mammals.

In the book, at the center of this warm sea, at exactly latitude 90° north, is a small island with a massive volcano; the expedition makes it as far as latitude 89° 59’ 15” north, lunching on the slopes of the volcano, basking in its triumph. In Verne’s original draft, Hatteras, dissatisfied at being unable to reach the pole itself, jumps into the volcano to finally reach true north. Under pressure from his editor, who found this suicide too severe, Verne changed the ending, so that instead Hatteras goes mad, and ends the novel in a catatonic state.

Far stranger is M. P. Shiel’s 1901 novel, The Purple Cloud. Shiel’s novel concerns one Adam Jeffson, a loathsome protagonist who joins an expedition to reach the North Pole. Jeffson, either directly or indirectly, kills the other members of his party one by one, so that he alone reaches latitude 90°. In Shiel’s inimitably pulpy and histrionic tone, the delirious Jeffson, who has traversed ice laden with emeralds and jewels deposited by meteors, finds at the pole, to his “sudden horror,” a circular, clean-cut lake. Shiel’s narrator continues:

The lake, I fancy, must be a mile across, and in its middle is a pillar of ice, very low and broad; and I had the clear impression, or dream, or notion, that there was a name, or word, graven all round in the ice of the pillar in characters which I could never read; and under the name a long date; and the fluid of the lake seemed to me to be wheeling with a shivering ecstasy, splashing and fluttering, round the pillar, always from west to east, in the direction of the spinning of the earth; and it was borne in upon me—I can’t at all say how—that this fluid was the substance of a living creature; and I had the distinct fancy, as my senses failed, that it was a creature with many dull and anguished eyes, and that, as it wheeled for ever round in fluttering lust, it kept its eyes always turned upon the name and the date graven in the pillar. But this must be my madness. . .

Unbeknownst to Adam Jeffson, at that precise moment a massive volcanic explosion unleashes a cloud of cyanide gas—the purple cloud of the book’s title—that wipes out every other member of the human population. Returning from this Arctic nightmare to a world of corpses, Jeffson goes mad, indulges in a bit of necrophilia, and then sets out to burn the world’s cities, traveling the globe lighting fire to the great metropolises. After eighteen years, he discovers, in Constantinople, one woman miraculously alive, and with this Eve, Adam Jeffson sets out to remake the world.

Both Verne and Shiel relied heavily on available science and narratives by actual explorers. Verne used French translations of Franklin, William Parry, John Ross, William Scoresby, and Shiel reliedon books like Nansen’s Farthest North and Joshua Slocum’s Sailing Alone Around the World. Beyond just informing the background of his novel, at times Verne’s narration shifts subtly, as though he believed the veracity of his story. Writing of the discovery of the open polar sea, Verne’s narrator comments: “This observation is of great practical importance; in effect, if ever whalers can reach the polar basin, from the seas of the north of America or the north of Asia, they are sure of getting full cargoes, for this part of the ocean seems to be the universal fishing-pond, the general resevoir of whales, seals, and all marine animals.” No longer the voice of a third-person narrator of a fictional novel, Verne is now a historian relating the events of an actual voyage.

But both writers inflected their works with pseudoscience as a means of adding additional symbolic layers. In Hatteras, the travelers, having reached the pole, palaver on the slope of a giant volcano that sits at the center of the Arctic, and Dr. Clawbonny explains to his companions the theories of a hollow earth, including Symmes’s, as well as another idea that orbiting the earth’s interior are two dim stars, Pluto and Prosperine (whose orbital motion accounts for the movement of the magnetic poles).

Shiel’s polar vision echoes the writings of Madame Blavatsky, who had described the North Pole as “the cradle of the first man and the dwelling of the last divine mortal, chosen as a Sishta for the future seed of humanity.” Shiel transforms Blavatsky’s ideas into a transgression bordering on the erotic: upon reaching the pole, Jeffson claims that “the very instant that my eyes met what was before me, I knew, I knew, that here was the Sanctity of Sanctities, the old eternal inner secret of the Life of this Earth, which it was a most burning shame for a man to see.” Shiel’s frenzied narration hyperbolizes the sexual metaphors inherent in any “conquest” of Mother Nature: that explorers headed to the pole in some sense sought to disrobe it. (Perhaps unsurprisingly, such a transgression leads, in both novels, to horror and madness.)

In a sense Shiel was on to something; certainly an innocence has been lost since the Age of Exploration wrapped up. So long as no one had reached the Pole, it could exist simultaneously in the imaginations of the scientist, the hollow-earth theorist, and the writer. The beauty of both Hatteras and The Purple Cloud is how each novel synthesizes these three different strands of thought. But both novels’ legacies suffered once the pole was actually reached, and no horror or mystery was found there—Peary and Nansen found only ice. Republished in 1929, The Purple Cloud had become quaint, the engines of its imagination now distant history. Likewise, Hatteras has fallen into obscurity, especially when compared to Verne’s other iconic novels of exploration: Journey to the Center of the Earth, Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea, and A Voyage to the Moon. In part this may be because those other exotic destinations—the earth’s interior, its deepest oceans, its distant moon—are still largely veiled from view. With such places still a mystery, even Verne’s nineteenth-century fantasies can still echo in our contemporary minds.

*

I had transcribed a few passages of Shiel’s novel to take with me to the Arctic, only to learn once I got there that one of my shipmates had brought her own copy—a ’60s reprint with a classic, pulpy cover of a purple-tinged cave strewn with bodies. Re-reading Shiel above the 78th parallel, it was tempting to dismiss his descriptions of diamonds in the ice, sentient lakes, and madness as nothing more than speculative fantasy—and yet, staring at those floating icebergs lingering above the water, it was harder to assert my own rational infallibility. That far north, the sun changes shape and multiplies, and ships float in the air; it is not a place to trust your eyes, or your beliefs. Barry Lopez writes that those strange visual tricks “serve as a caution against precise description and expectation, a reminder that the universe is oddly hinged.” Our ship was eight hundred miles from the pole, as close as we would get, and even there my vision had gone strange and untrustworthy.