I drove a car across the country once. It took three weeks and was financed by a rock magazine. Two years after the trip, a handful of people from California with exceptionally comfortable office chairs considered making a movie out of my experience. It was a very confusing process. Enthusiastic strangers with German eyeglasses kept asking me how I imagined this film would look, which I found difficult to elucidate; I assumed it would look like the video for Tom Cochrane’s “Life Is a Highway,” partially because of the lyrical content but mostly because I (sort of) looked Canadian before I grew a beard. That was not the answer they were anticipating. I was given a strong impression they were hoping I would say it would be a lot like Trainspotting, although maybe they were just trying to figure out if I could put them in contact with local drug dealers. They also wanted me to sign a 780-page contract that would give time control over my “life rights,” which meant they would have been able to make me an ancillary character in You, Me and Dupree.

My theoretical Road Movie would not have been interesting and does not exist, although those two points are not necessarily related. I have no doubt that it would have followed the conventional Road Movie trajectory, which has remained intact since before The Wizard of Oz. This trajectory is as follows:

- A character experiences abstract loss and attempts an exodus from normal life.

- The character reinvents his or her self-identity while traveling.

- Along the way, the character encounters iconic individuals who (usually) illustrate authenticity and desolation.

- Upon the recognition of seemingly self-evident realizations, the character desires to return to the point of origin.

I assume the hypothetical Road Movie I was not involved with would have been built on the most elementary of Road Movie clichés: where you’re going doesn’t matter as much as how you get there. But that philosophy raises at least three questions, some of which are equally cliché but all of which are hard to answer: What is a Road Movie, really? Why do so many directors (from so many different eras) long to make them? And what makes movement any more inherently interesting than—or even all that different from—staying in one place?

*

The defining domestic road narrative is Jack Kerouac’s 1957 novel On the Road, a novel that readers either take much too seriously (at least in the opinion of dead author Truman Capote, who didn’t even classify the prose as writing) or not seriously enough (if you happen to be non-dead author John Leland, who just published a book titled Why Kerouac Matters). A film adaptation of On the Road has been percolating for years; still scheduled for 2009, the movie is slated to be produced by Francis Ford Coppola and directed by Walter Salles, a Brazilian-born filmmaker already known for crafting semi-epic road pictures (most notably 2004’s Motorcycle Diaries, but also 1996’s Foreign Land and 1998’s Central Station). It was my intention to interview Salles for this piece, but he’s currently in South America and unwilling to chat. He did, however, email me a two-thousand-word essay1 he wrote for a Greek film festival, which is akin to getting an extremely long answer to a question that was never technically asked.

The essay is (rather straightforwardly) titled “About Road Movies.” Salles suggests that all of this starts with The Odyssey of Homer and reflects a specific kind of human discovery. Here are a few of his core thoughts, mostly unedited:

The early road movies were about the discovery of a new geography or about the expansion of frontiers, like Westerns in North American cinema. They were films about a national identity in construction. In more recent decades, road movies started to accomplish a different task: they began to register national identities in transformation.

This first point addresses something almost everyone who talks about Road Movies inevitably feels obligated to reference: the idea of moving west across the country is such a deeply American tradition that virtually all Road Movies borrow on this motif. This is even true when a movie consciously embraces the opposing philosophy. In 1969’s Easy Rider, Peter Fonda and Dennis Hopper start in California and travel east. They’re part of the counterculture, so they move in the opposite direction of manifest destiny. When Jack Nicholson’s character says things like “This used to be a hell of a good country. I can’t understand what’s gone wrong with it,” he is essentially suggesting a discovery of America in reverse.

In terms of architecture, road movies cannot be circumscribed to the traditional three-act structure that define the screenplays of so many mainstream films. Road movies are rarely guided by external conflicts; the conflict that afflicts its characters is basically an internal one…. I have the impression that the most interesting road movies are the ones in which the identity crises of its main characters mirror the identity crisis of the culture these characters originate from, or are going through.

Salles’s second point is interesting because—though true—it often represents the easiest criticism of any movie focused on characters who seem obsessed with movement for the sake of movement alone. For example, there really is no conflict in Smokey and the Bandit (it’s actually easier to understand the plot by listening to the three-minute Jerry Reed song “Westbound and Down” than by watching the movie itself). However, Smokey and the Bandit becomes far more compelling if viewed from the perspective that Burt Reynolds is the idealized embodiment of how a masculine, semi-blue-collar Southern male would think about the world in 1977 (i.e., not taking it seriously and not giving a shit about anything, including the things he knows he should give a shit about, such as the pugnacious optimism of Sally Field).

Because of the necessity of accompanying the internal transformation of its characters, road movies are not about what can be verbalized, but about what can be felt. About the invisible that complements the visible. In this sense, road movies contrast dramatically with the present mainstream films, in which new actions are created every five minutes to grab the attention of the spectator. In road movies, a moment of silence is generally more important than the most dramatic action.

Salles’s third point is more debatable. It speaks to the divide between people who claim they like “films” and those who willfully insist they prefer “movies.” The true question becomes this: are movies more interesting when something is happening, or are movies more interesting when nothing is happening? In the case of Vincent Gallo’s sublimely gratuitous The Brown Bunny (2003), the latter argument feels more accurate; what makes that film hypnotizing is its ability to replicate the focused boredom of authentic highway driving. But this is usually the exception. There are cataclysmic, melodramatic deaths at the end of 1967’s Bonnie and Clyde and 1991’s Thelma and Louise. My assumption is that Salles would argue that those specific events were less important than the (mostly) unspoken agreement of the characters’ decision to die together. But that’s not how it seems when the movies are actively consumed, which indicates one of two things: either Salles’s description of Road Movies is imperfect, or those two examples aren’t Road Movies at all. Maybe they’re just movies that happen to have roads in them.

*

“Going from point A to point B is kind of the obvious criteria here.” This is Gus Van Sant, talking via telephone. He is speaking very cautiously; the questions I’ve asked him are so vague and abstract that I think he suspects I’m trying to trick him into saying something he doesn’t believe. “In a movie like Gerry, the characters are looking for a road, which really isn’t the same thing as a Road Movie. All of this probably comes from our own history—wagon trains and literal trains and exploring the West. But by the time we got to the 1960s, it didn’t really matter which direction you were going. Ken Kesey had business on the East Coast, so that required a reversal.”

The reason I am interviewing Van Sant is two-pronged, although it appears neither of my prongs are particularly sharp. The first reason is that I was under the impression that he’s agreed to direct an upcoming version of The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test, Tom Wolfe’s nonfiction account of the aforementioned Kesey’s LSD-fueled 1964 bus trip across the United States. As it turns out, Van Sant has yet to officially sign on to this project (he said he was still in the midst of negotiating the deal and writing the script). My second reason for calling is that I closely associate Van Sant with the Road Movie genre, which (in retrospect) is totally specious. A lot of his films are Road Movies in my memory, but they weren’t when I re-watched them. As Van Sant noted, Gerry doesn’t have a road. My Own Private Idaho starts on a highway and ends in Rome (where all roads are said to lead), but everything in the middle seems detached from movement. In Drugstore Cowboy (1989), the characters stay in motion and actively take a road trip, but it’s still not a Road Movie.

That said, there is something about Van Sant’s work that (perhaps inadvertently) inhabits the relationship between travel and life experience. His interest in The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test is not surprising: besides holding a career-long cinematic interest in drug use, Van Sant claims to have crossed the country by car at least twenty times in his life and still drives from his home in Oregon to Los Angeles on a regular basis.

“I don’t know if I’ve ever shot a physical landscape through the window of a moving car, but I’ve always thought the idea of road stories on film was the central metaphor of a beginning, a middle, and an end,” he says, slightly challenging Salles’s notion that Road Movies don’t operate like traditional three-act plays. “The trip creates a natural progression through the middle of a film. I think a story like On the Road, for example, will actually be more effective as a film than as a book. Going from point A to point B is not what really holds a novel together. But movement can hold a movie together.”

In the hopes of finding clarity, I ask Van Sant what he thinks a Road Movie is. Somewhat predictably, his response makes things more confusing (and also seems to contradict something he already said about one of his own films).

“Well, if Duel isn’t a road movie, then such a thing as Road Movies doesn’t exist,” he says. “But does there even have to be a road at all? Is 2001: A Space Odyssey a road movie? I think that you could argue that it was.”

This, I suppose, is true. You could argue that 2001 was a Road Movie, just as you could argue that My Dinner with Andre is a Road Movie of the Mind. But that kind of argument leads nowhere. The more telling detail is Van Sant’s mention of Duel, Steven Spielberg’s 1971 made-for-TV movie about an unassuming businessman—a person literally named “David Mann”—in a Plymouth Valiant who finds himself in an inexplicable personal war with a flammable tank truck driven by a faceless stranger who wants to kill him. Duel eliminates the idea of a road trip as some sort of spiritual quest. Instead, it exclusively ties its story to the most fundamental elements of the genre: people, vehicles, and the nonmetaphorical physicality of the earth itself.

*

The six types of narrative conflict are usually described in the following manner: Man v. Himself, Man v. Man, Man v. Society, Man v. Nature, Man v. Machine, and Man v. God. In his essay, Salles writes that Road Movies are usually internal conflicts, so he’d probably see Duel as Man v. Himself; if consumed completely devoid of subtext, the screenplay for Duel seems like an obvious Man v. Man scenario. But those would both be attempts at simplifying what a Road Movie is about, and I’m not sure if it’s that simple. To me, Road Movies often seem to adhere to this equation:

(MAN + MACHINE) – (GOD V. SOCIETY) + NATURE/HIMSELF

Duel, Vanishing PointTwo-Lane Blacktop,

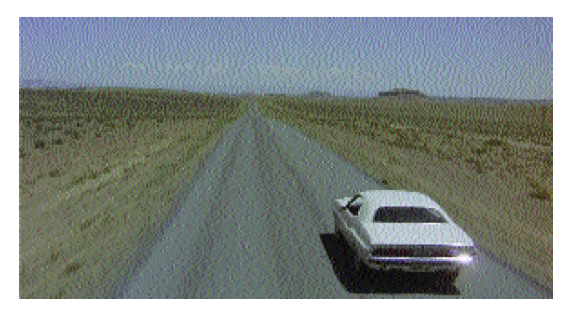

Made with a budget of $1.3 million, Vanishing Point is about a 1970 Dodge Challenger, driven by Kowalski, a stoic portrayed by an actor named Barry Newman, who spends a lot of time looking like Elliott Gould and acting like Dustin Hoffman. (Interestingly, the director wanted the role to go to Gene Hackman.) In order to win a meaningless bet with a Benzedrine dealer, Kowalski attempts to drive the white Challenger from Boulder, Colorado, to San Francisco in fifteen hours. As the trip progresses, the Challenger evolves into a sort of memory machine that allows Kowalski to mentally replay past episodes from his life. That’s pretty much the whole movie. Two-Lane Blacktop was made more cheaply (for an estimated $850,000) and managed to be even more plotless: two drag-racing slackabouts (musicians James Taylor and Dennis Wilson) get into a cross-country Route 66 road race against a drifter in a GTO (Warren Oates). This turns into a three-way sexual competition for an extremely annoying hippie (Laurie Bird). The story is generally incomprehensible, partially because untrained actors Taylor and Wilson tend to oscillate between acting unnaturally stiff and supernaturally high.

Still, there are two things that make Vanishing Point and Two-Lane Blacktop compelling, regardless of how underwritten they feel in the present tense. The first is that both films are relentlessly auto-centric. The audience is constantly shown images inside the rearview mirror or over the top of the hood. The sound of the vehicle engines is extremely high in the audio mix. You get used to seeing people gripping a steering wheel while cocking their skull slightly to one side. “I’m gonna make the car the star,” claimed Vanishing Point director Richard C. Sarafian, but that’s not really what happens; in both movies, the process of driving is the star. The other (more obvious) link between Vanishing Point and Two-Lane Blacktop is how they conclude. In the former, Kowalski drives his Dodge into a pair of bulldozers and explodes. Man and Car die together, and there’s no explanation as to why. Two-Lane Blacktop ends even more abruptly: while the characters are racing in Tennessee, the movie’s sound drops out and the celluloid film itself burns up.

If you like either or both of these movies, you almost certainly love these particular endings and find them “existential.” If you dislike these movies, you probably find these finales meaningless (and not in a good way). Yet Vanishing Point and Two-Lane Blacktop seem to solve the Road Movie Equation I mentioned a few paragraphs earlier. It’s no longer a question of “versus.” Now the equation reads more like this:

(MAN + MACHINE) – (GOD < SOCIETY) + NATURE/HIMSELF

*

What all this boils down to is that there are two idioms of Road Movies, and the only thing that truly connects them is the presence of asphalt. Films in the vein of Vanishing Point are external, aggressive, mechanically oriented abstractions where the characters remain static (this genus also include movies like The Cannonball Run, The Road Warrior, and the recent Quentin Tarantino project Death Proof). In contrast, a movie like Wong Kar-wai’s recent My Blueberry Nights (or Two for the Road, or Little Miss Sunshine) is supposed to be meandering, personal, and transformative. Essentially, you are either (a) going nowhere fast or (b) going somewhere slow. The fact that we all unconsciously understand those paradigms is how Road Movies succeed.

But sometimes it’s how they fail.

The themes we all understand are not always true.

One of the best Road Movies from recent years is Kelly Reichardt’s Old Joy, a minimalist indie project set in the Pacific Northwest. The movie is about two old friends (Will Oldham and Daniel London) who have grown apart over time but decide to take a road trip together. Were this a conventional Road Movie, that experience would foster rediscovery—the two friends would address their differences and bind a new friendship. But this does not happen. They do not argue, evolve, or suddenly recall why they originally liked each other. It’s a slow, hyperpersonal movie that offers no transformation whatsoever.2 The characters have nothing profound to say to each other, and that is disenchanting. But because they are in a car together, they can still talk. When two people are sitting in a car, they don’t have to look at each other. They don’t have to be interesting or funny or even themselves, because they’re not there for entertainment; they are there to get somewhere else. That’s what makes movement more interesting than staying in place: Road Trips exist outside of reality. Cars are not just memory machines. Cars are avoidance machines. And we will always watch anything that keeps us from being here, regardless of where that is (or isn’t).