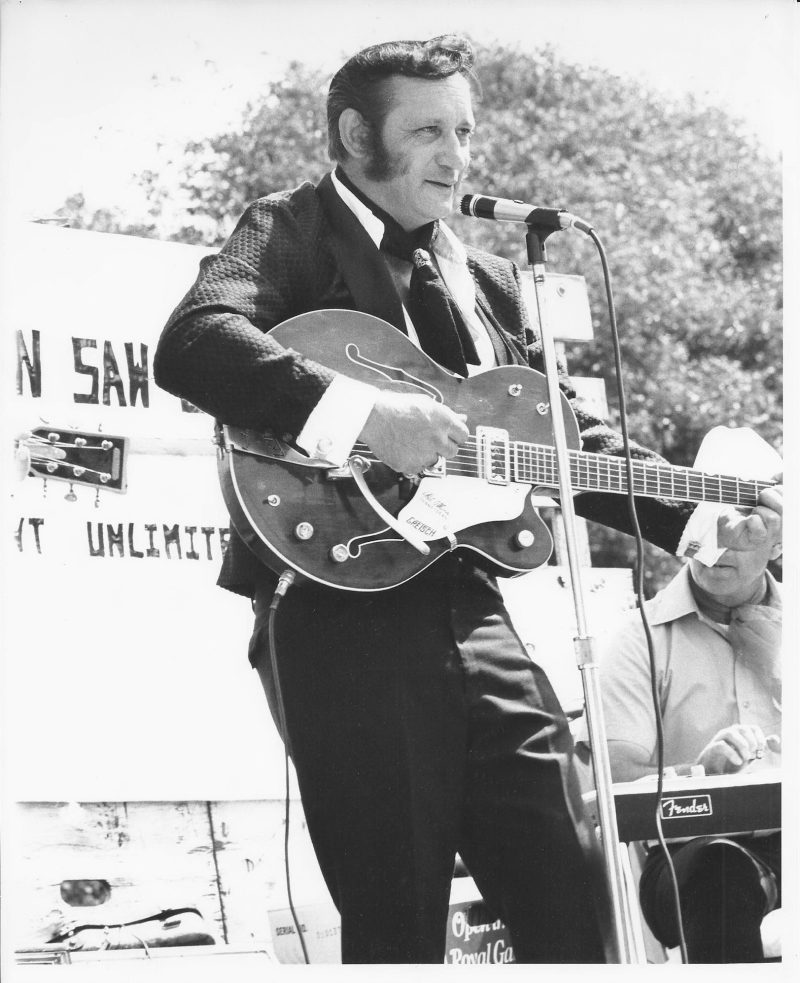

In photographs, everything about Buzz Martin looks unnaturally large: big nose, big forehead, big lamb-chop sideburns that draw attention away from the big ears behind them. “The Singing Logger” was seldom photographed without an ax or a guitar, probably because his lumpy hands hung awkwardly without something to hold. He wore his flannel shirtsleeves rolled up near his shoulders to reveal formidable white biceps offset by tan, leathery forearms that once measured seventeen inches around—the same size as Andre the Giant’s. His top three shirt buttons never seemed to find their loopholes. It’s hard to tell, from the old album covers and family photos, whether the deep lines on Martin’s face were wrinkles or scars. In the declining years of the timber industry, in the logging camps of the Pacific Northwest, Buzz Martin’s legend grew to Paul Bunyan proportions; he was a larger-than-life symbol of the logging world’s values, its resilience, and its screwball humor.

For about a decade, beginning in the late ’60s, the Singing Logger found enough success as a minor country-music star to hang up his lumberjack’s cork boots and tour bars, logging camps, and music festivals across the country. In his brief career, Martin wrote what would become nearly the entire canon of modern logging music. On his six albums—all released between the mid-’60s and early ’70s—he wrote forty-four original songs; nearly two-thirds are about logging.

Singing about blue-collar work has always been a rite of passage for country singers, but in the middle of the last century, a notable group of songwriters made their careers producing songs about a single occupation. Marty Robbins was a suburban kid turned racecar driver who made it big performing songs about gunslingers and cattle ranchers. Red Sovine, a former hosiery factory supervisor, found fame singing intensely melodramatic songs about the lives of long-haul truckers. But unlike many of his peers in the often-superficial and showy genre we’ll call “occupational country,” Buzz Martin was a direct product of the world he sang about. He approached his subject with a keen eye for detail. Martin preferred emotional realism to melodrama, and if his songs glorified the logger as a hero, just as often they painted a punishingly bleak portrait of the job. He wrote from the perspective of a keenly self-aware insider, resulting in a discography—most of which has been out of print since the ’70s—that provides a rare glimpse into a famously closed and protective segment of blue-collar America. Buzz Martin didn’t just document logging culture, he narrated the slow death of the Northwest’s biggest industry and the broken people it took down with it. Then, after a brief bout of fame, Martin returned to the wilderness and never came back.

*

Martin was born in 1928 in what has been described alternately as a tent and a “hops shack” in Coon Holler, Oregon, a hamlet so small it doesn’t show up on maps. Martin sings that as a dirt-poor kid he picked berries and scavenged for bottles with return deposits in order to buy candy and new clothes. In the late 1930s, he began to lose his sight, and at age thirteen he was sent to the Oregon School for the Blind, in Salem, where he first picked up a guitar. While at the school, he received a corneal transplant and regained his sight. Martin told friends and family that his new eyes had come from a dead prison inmate.1

His father, Harry, died while Martin was away at school. His mother, Stella, died shortly after his release, when he was fifteen. Martin didn’t speak much about his parents, and never sang about them. As a teenager, he went to live with his sister and her considerably older husband, a musician and amateur instrument-maker named Bill Woosley. They lived in Five Rivers, a tiny community at the midway point between the Willamette Valley and the Oregon Coast. The closest town was Alsea, a now-dilapidated truck-stop town in the thick of the Siuslaw National Forest. The family cabin did not have electricity—though there was a battery-powered radio, which was used only for listening to the Grand Ole Opry—so they complemented logging work by playing music of their own. Martin, with encouragement from his sister, quickly became the singer of the house.

Martin was eighteen when he began working in the woods. World War II had just ended, and demand for timber had grown rapidly—first to support the war effort and then to keep up with the postwar economic boom. Martin, like many young loggers, first worked as a whistle punk, controlling a loud, steam-powered whistle that kept loggers in communication with one another. “The whistle punk is usually about sixteen to eighteen years old and the hardest boiled egg in the outfit,” Oregon logger D. D. Strite wrote in 1924. “He is usually deaf, dumb and blind.”

Martin didn’t stay a whistle punk for long. “He worked every job there is from cutting timber to high climbing,” Salem-based radio host Dick Bond explains in the liner notes for Martin’s first record. “Buzz has worked every kind of machine from a cat to a giant letourneau.”2

In his twenties, Martin began singing for the workers in logging camps, a rich tradition in the industry. “Camp entertainment was of, by and for the woodsmen,” James Stevens wrote in “Shanty Boy,” a 1925 Paul Bunyan fable. “In Paul Bunyan’s camp there were hypnotic story-tellers, singers who could make you laugh and cry in the same moment.” The best singers were often the laziest workers, Stevens wrote, but they kept spirits high in the bunkhouses.

The songs performed in logging camps and logger bars in the first half of the century were rarely recorded or formalized. Their origins were often a mystery even to the singers performing them. “It’s a real problem,” says Vancouver folklorist Jon Bartlett. “We’re talking about vernacular language and we’re talking about informal settings. People didn’t write about these songs, they took them for granted. We’ve got about twenty or thirty books about logging in B.C., and I don’t think any of them mention songs.”

The compositions that survived the oral tradition were simple in structure and catchy as hell, most of them based on pop and country tunes from the 1920s. Perhaps the most persistent of these was James Stevens’s own “The Frozen Logger,” a song Martin knew well and often played for his children. He would include the song on his first album. The song’s outrageous but plainspoken lyrics seem to have inspired Martin’s own songwriting voice. It begins:

As I sat down one evening within a small café

a forty-year-old waitress to me these words did say:

“I see that you are a logger, and not just a common bum,

’cause nobody but a logger stirs his coffee with his thumb.

My lover was a logger, there’s none like him today;

if you’d pour whiskey on it, he could eat a bale of hay.”

At twenty, Martin married Lela Elizabeth Erickson, a seventeen-year-old girl he called “Biscuit,” and they spent much of the next ten years building a family—a decision Martin occasionally lamented in song, warning listeners about settling down too soon. By his early thirties, he had become serious about performing his original music. He played in logging camps around the state and bars along the Oregon Coast. He slowly built a reputation among western Oregon country music fans.

In 1963, Martin sent a letter to a DJ and TV host named Buddy Simmons, who had a weekly show on the ABC affiliate in Portland, Oregon. Simmons received a lot of letters. This one was different. “This letter was written with such honesty and personal sincerity that after reading it I felt as if I already knew the man,” he recalled later on the back of a Buzz Martin album. Simmons invited Martin to play on his TV show, The Channel 2 Hoedown. He played “Sick of Setting Chokers,” about a new logger who hates everything about the profession, and “Whistle Punk Pete,” the tale of a pint-size whistle punk who trains for a better position by buttoning up his overweight girlfriend’s girdle each morning. Those two songs would soon make up the first Buzz Martin 7-inch single.

That these jargon-packed songs made such a splash among non-loggers is a testament to both Martin’s crafty songwriting and Portland’s hillbilly roots. In 1963, while Seattle was booming and celebrating a recent World’s Fair and the construction of the Space Needle, downtown Portland looked about the same as it had thirty years earlier. Portland had a small but vocal counterculture, and it had rock and roll—the Kingsmen recorded their wild, definitive version of “Louie, Louie” in the city around the same time as Martin’s TV appearance—but mostly it had trees. The city was (and largely remains) surrounded by timberland, and much of the area’s economy was built, directly or indirectly, on logging.

Where There Walks a Logger, There Walks a Man, Buzz Martin’s debut full-length, was released in 1968 on the Tacoma, Washington–based Ripcord Records. (Martin’s producer, Bob Gibson, cofounded the label; Martin was the only artist on it.) All but one of the album’s ten songs center around logging. The exception is a swaggering honky-tonk number about making out in a Model A, because “almost every logger that I’ve known has had a Model A at some time or another,” Martin explains in a brief spoken intro.

Martin starts the record with “Used Log Truck,” a beautifully paced talking-blues parable about the perils of choosing self-determination over security. The song begins with promise, its second-person protagonist going into business for himself with a log truck he bought on credit. Soon the truck begins to fall apart. Just when it seems Martin will wrap things up with a clever punch line, the mood abruptly darkens:

When you do get the haul, you work on it all night.

Pretty soon you and your wife have a fight.

She don’t understand, it’s just gotta be.

She says, “You love that truck more than the kids and me.”

She cries a lot lately and complains and howls

when you wipe your greasy hands on her new white towels.

The washing machine is broke, the dryer motor’s stuck,

and so are you, with your used log truck.

The record was a hit for Martin—his son Steve claims that it moved a total of 250,000 copies—but Martin’s biggest moment was yet to come.

In 1969, Bob Elfstrom was in the middle of filming his intimate free-form documentary on Johnny Cash, shooting a scene in a dressing room at Portland’s Memorial Coliseum. “John was absolutely exhausted,” Elfstrom remembers. “I never saw him say no to a fan, but he really just wanted to get back to the hotel and get some sleep.” After the concert, Cash hosted a meet-and-greet with sweet old ladies and gushing farm boys. Waiting among them in the cramped white dressing room, with his wife beside him, stood Buzz Martin. Three years Cash’s senior, in the footage Martin looks like the Man in Black’s long-lost older brother. “I don’t know who got him into the dressing room,” Elfstrom recalls. “I just know that [Cash] recognized the authenticity of both of them. This guy was so adorable. There was something so earnest and real about him.”

The three-minute clip in Elfstrom’s film begins with a weary Cash helping Martin to yank the capo off of an acoustic guitar. Martin’s hands appear to be trembling.

Cash asks Martin to play his best song. “I think probably the best songs [are] on the album there, John,” Martin stammers, motioning to June Carter Cash, who holds the record in her hands. “I’d like to do a couple that are not on the album, if that’s all right.”

Cash gives a tired nod, and Martin begins to play. His strumming is arrhythmic and jagged; his speak-singing trembles through an initial bout with the giggles as he catches the face of Johnny Cash, which begins to glow in his periphery.

My little woman’s like a batch of homemade biscuits.

How she’ll turn out, I never really know.

Sometimes she’s warm and soft and nice, like a fresh-baked little sweet roll.

But sometimes she’s cold and hard like half-baked sourdough.

Johnny and June burst into appreciative laughter as Martin delivers the hook: “I’m gonna have a hard time butterin’ Biscuit up tonight.” Elfstrom’s camera catches Biscuit—even the couple’s children knew her by that name—frozen in a bashful half smile in the corner of the room, occasionally glancing over at June. Abruptly, the song ends.

“You really put words together good,” a still-chuckling Cash tells Martin. In the next scene, Martin implores Cash to attend a logging competition he’s playing the next night. Cash, on a tight touring schedule, politely declines.

*

In 1971, Johnny Cash invited Martin to appear on his popular Johnny Cash Show, filmed for ABC at the Ryman Auditorium, home of the Grand Ole Opry. Before the show, Martin’s manager took him to downtown Nashville to buy a flamboyant, TV-ready country-music tuxedo. When Martin came to the auditorium looking like a shimmering, besequinned George Jones, the show’s producers promptly sent him to the changing room with a checkered shirt and jeans. When Cash introduced Martin, he reportedly said, “The only difference between me and Buzz is, he’s singin’ about lumberjacks and I’m singin’ about cotton pickers.” The line would become Martin’s calling card, but the Buzz Martin episode of The Johnny Cash Show never aired. The only evidence it took place at all is a fuzzy photograph from the grandstands of the pair sitting onstage together, drenched in stage lights.

Nonetheless, the experience whetted Martin’s appetite for fame. After returning to Oregon, he recorded his third album (and his first collection of non-logging songs), A Logger Finds an Opening. “Butterin’ Up Biscuit” is the standout track, but the collection also features some sharp satire: the subtly psychedelic “Automated Love” envisions America’s enthusiasm for gadgets leading to an apocalyptic robot-sex revolution; the catchy “I Just Happened to Be in the Way” chronicles a country bumpkin’s run-in with a sleazy talent scout.

The album is compelling, and it might indeed have represented Buzz Martin’s big break, had his national television debut gone according to plan. Instead, A Logger Finds an Opening seemed to tie Martin’s fate with that of the timber industry. The title (and tone) of Martin’s subsequent album, The Old Time Logger, A Vanishing Breed of Man, feels like a proper acknowledgment of the Singing Logger’s fast-fading spotlight. On that album’s title track, the singer’s words are grateful, even spiritual, but his tone is noticeably edgy. “I thought of the young men replacing the old men,” he sings with the warble of a sentimental old drunk. “I guess that’s the way nature had it all planned.”

Martin didn’t want to leave music, but he also had mouths to feed. As his career began to wane, in the mid-’70s, he signed sponsorship deals with a pair of chain-saw companies, first the American McCulloch Motors Corporation, then later the Japanese Echo chain saw company. In addition to appearing in print advertisements, Martin toured with the latest-model chain saws in tow, performing live demonstrations and playing trade shows to supplement his touring schedule.

After playing at a bar in Washington State, a club owner refused to pay Buzz and his band. “This guy was really big,” Buzz’s son Steve says, recalling a story told by one of Martin’s old bandmates. “So Dad went out to his rig, brought in his chain saw, and started it up.” Martin lopped off the end of the bar to prove he meant business. The owner threatened to call the police. “Go ahead,” Martin told him. “Before they get here I’ll have your bar destroyed.” The club owner paid, and Martin drove off to his next show.

Dona Moxon, a marketing specialist for Western-wear brands, often booked Martin in Eureka, California. He played spaghetti feeds and trade shows—gigs that were not among his greatest ambitions. “There was definitely a dream,” Moxon says. “But he was realistic. He knew he had a family and he had responsibilities and he couldn’t run off and go to Nashville. He was a family man first.”

In a bid to keep that family together, Martin folded four of his five children into his band. (A daughter-in-law, and some of his children’s assorted significant others, would later follow.) Biscuit toured with the band, too, and was responsible for hand-designing glitzy ’70s stage outfits for the whole crew. “Everything was polyester,” Moxon recalls. “There was so much of it.”

The band, which Martin dubbed “The Chips Off the Old Block,” toured alongside him as often as it made financial sense—as it did for bigger club dates and promotional appearances—for about two years. When it came time for a new album, Martin asked the folks at Echo for help. They agreed to pay for the album in exchange for a small promotional mention, and because Echo’s distribution company had just changed its name to Golden Eagle, it was decided that the album title would be Solid Gold. Martin recorded it at his usual studio, Ripcord, this time with his family backing him.

Solid Gold is a bizarre and occasionally charming record. Martin appears on the cover with a long black mullet and gigantic lamb-chop sideburns, with Grateful Dead–style psychedelic text swirling around his head. The album is made up primarily of up-tempo, rockified takes on Martin’s own classics, but also features a few covers performed by his teenage children. For reasons that were a mystery to everyone but Martin himself, it was recorded to sound like a live album—but with no audience. One can only assume that there was a miscommunication, and that Martin expected crowd noise to be dubbed in afterward, and it makes for some extremely awkward moments. At one point, Martin banters with the make-believe crowd, saying, “Hey, you are a great audience” to dead silence. Later he nearly starts a brawl with an imaginary audience member whom Martin mistakes for “Earthquake Migoon,” a character of his own invention.

The heartfelt, genuine woodsman is nowhere to be found on Solid Gold. By the standard Buzz set with his own early records, Solid Gold was a disaster both creatively and financially. But the album doesn’t deserve the blame for his fading prospects. “His music career was on the downturn,” Martin’s son Steve remembers. “The spotted owl came in and logging was a bad word.”

Country music was in serious transition, and so was logging. Federal timber regulations became more complex in the wake of new environmental-impact studies, and increased mechanization changed the public perception of the logger from that of a grizzled lumberjack to that of a faceless machine. Though Oregon’s timber industry wouldn’t begin its free fall until the late ’70s, in 1973 logging culture was an entirely different commodity than it had been when Martin first sang of widow-makers and whistle punks. Still, Martin was tireless in his defense of the industry. “We’re growing more timber than we’re harvesting right now,” Martin said in a 1976 recording for the Smithsonian, which hosted him at its bicentennial concert in Washington, D.C. “We’re not running out of timber, we’re taking care of it… Sure, there were some bad loggers, and there may be a couple left around the country, but they’re getting smarter.”

Recorded in 1973 for the Ranwood label (then co-owned by Lawrence Welk), The Singing Logger is, despite its title, not about logging, though it’s as solid a collection as Martin ever put together. Martin found himself working with an outfit called the Larry Booth Band. Though Larry’s older brother Tony was far better known (having helped craft a hard-driving and twangy style of country known as “the Bakersfield sound”), the former put together one hell of a band for Martin’s session. Drummer Archie Francis plays funky patterns primed for future hip-hop sampling, and steel guitarist J. D. Maness (a prolific studio musician who would later cut the mournful slide work on Eric Clapton’s “Tears in Heaven”) takes a curious approach to the songs that occasionally sound closer to the Middle East than the American West.

The record finds Martin both sharp (“Dump Truck Drivers” is a rollicking tribute to a breed of truckers rarely romanticized in song) and sentimental. “My Growing Up Years” and “Always Plenty of Water” look back on the singer’s brutal childhood through a soft-focus lens. Despite its high production values and new label, The Singing Logger, like its predecessors, failed to break Buzz Martin into mainstream America. Soon the money dried up for good. He recorded one more album, a collection of gospel songs, that was never released. In 1974 he sold the rights to his catalog to Lawrence Welk’s publishing company, and effectively ended his recording career.

In 1979, Martin flew north to Alaska in search of logging work. He soon found it, driving trucks and running heavy machinery. There were still logging camps and bunkhouses in the remote reaches of Alaska, and Martin performed songs for the workers, just as he had in his youth. Refreshed, he started on a collection of songs about his new home state. It, too, would never be completed.

In 1983, Martin’s grandchildren and daughter-in-law went to visit Martin and Biscuit at his trailer on Alaska’s Chichagof Island. His son Steve stayed back in Oregon for work. One Saturday morning, Martin headed out alone into the woods to scout the area for hunting spots. Hunting season started on Monday, and Martin wanted to be prepared. But he didn’t come home that night, as expected. The authorities were called in the next day, and helicopters searched overhead for signs of Martin. It was Steve’s seven-year-old son, Brandon, who found his grandfather not far from the trailer, lying facedown in a tide pool. It was, Steve thinks, a freak accident. Martin had a blunt wound to his head, and rescue workers assumed he had slipped and hit his head on a rock, then had fallen unconscious into the water and drowned. He was fifty-five years old.

These days Steve Martin lives on a dead-end street in Lebanon, Oregon. His house is surrounded by timber and old logging roads, and inside there are pictures of horses and illustrated passages from the bible. At sixty, Steve is built like his father, only a little heftier and sporting a pair of wire-frame glasses. He recorded an album of Buzz Martin covers under his own name and even reissued some of his dad’s old music, complete with vinyl pops and hisses, in 2005. He secured the rights to his father’s catalog some years ago, but no labels have ever come calling. A few times a year, he’ll play the songs at a local school or for the members of his church.

When he sings, Steve sounds an awful lot like Buzz Martin, though his voice is a little deeper now that he’s older than his father ever was. Some songs are punctuated with chuckles reminiscent of his father’s laughter in Johnny Cash’s green room in 1969. He gets choked up singing the chorus to one of the unreleased gospel songs (“And I thank you, lord, for the blessings you gave us. / And that there’s still some timberland”).

Though he never lived, Paul Bunyan has a headstone in Kelliher, Minnesota, across the street from the Road Runner Drive-In. It is disconcertingly small, and the epitaph reads like a punch line: “Here Lies Paul, And That’s All.”

Buzz Martin’s final resting place isn’t a roadside attraction. He has a faded headstone at Lone Oak Cemetery in Stayton, Oregon, inscribed with a pine tree and a familiar title: “The Singing Logger.” Martin’s true monument, though, is harder to find. It’s a warped slab of vinyl in a cardboard sleeve that’s torn at the spine. It waits silently to be discovered, sandwiched between Whipped Cream and Other Delights and Sing Along with Mitch, on the bottom shelf of a Goodwill somewhere off Route 101.