Something unsettling resides at the heart of the most beloved books for very young children—that is, the literature for illiterates. This note is a belated attempt to grapple with the horror of infinite regression as it manifests in certain of these works, and perhaps to sound the alarm for parent-caretaker voice-over providers who are too sleep-deprived to notice what’s actually going on.

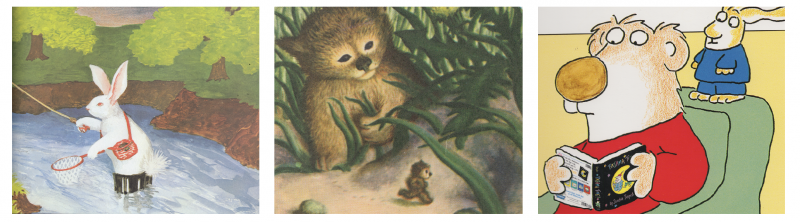

In Margaret Wise Brown’s Little Fur Family (1946, illustrated by Garth Williams), a small, hirsute child of indeterminate species spends a day in the woods. This gentle narrative of forest exploration appears completely anodyne. But at one point, the Little Fur Child meets another hairy biped, a fraction of his size. If we were to follow this second child (call it the Littler Fur Child), would he come across a third one, even smaller? There would be a fourth, a fifth… Maybe that speck on the edge of your page is not a bit of grime but the furry creature’s 17th or 717th iteration. Illustration has no limit. You could show a picture of the inside of an atom if you wanted. Maybe the 10756th LFC is dancing, invisible, on the tip of your knuckle as you read this sentence.

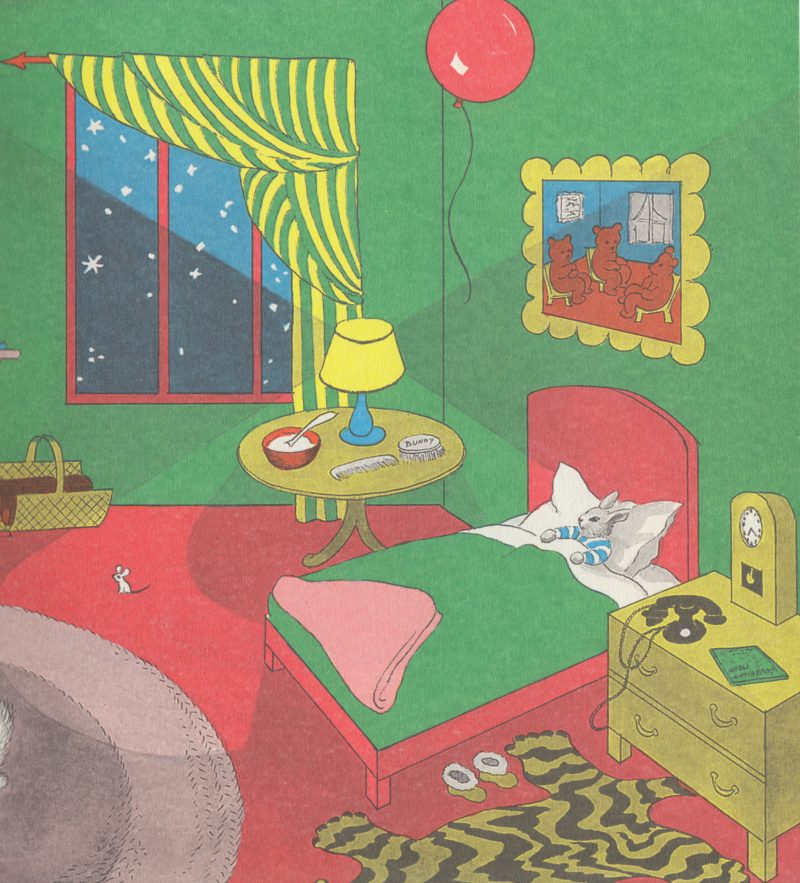

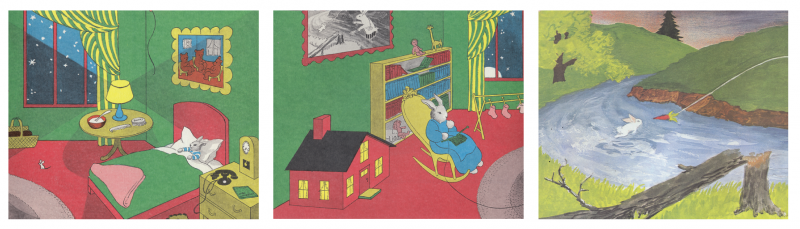

At the midway point in Margaret Wise Brown’s even more beloved Goodnight Moon (1947)—that instant when the book becomes a sort of palindrome and bids good night to all the things in the room that have just been itemized—something curious happens. The pictures of the cow jumping over the moon (center) and the three bears sitting on chairs (right) remain hanging, but visible on the left-hand wall of the curiously structured (non-Euclidean?) room is a painting that has gone unremarked. (The illustrations are by Clement Hurd.) A rabbit in waders is fly-fishing with a carrot, its quarry apparently a smaller rabbit.

A charming tableau, but what is it doing here, unidentified, in this universe where everything is named and named again? In fact, Brown/Hurd provides a surreptitious ID: barely visible, on the shelf behind the rocking bunny, is an awkwardly opened copy of The Runaway Bunny (1942)—a book by Margaret Wise Brown, with illustrations by Clement Hurd.

The semi-comatose parent-reader voice-over provider can be forgiven for missing these details the first few dozen times. For (as my reader will have guessed) the third picture is none other than a scene from The Runaway Bunny. Is this simply an in-joke, or are Brown and Hurd up to something else? The allusion to The Runaway Bunny is subversive, like a shot cut from a bad dream and spliced into this prose-and-pictures pacifier. In that rabbit tale, the mother-child bond is shown as loving but also relentless—there is no escape. It’s as though, in this gentler story, the creators could not help giving a taste of the psychodrama to come.

Sandra Boynton’s Pajama Time! (2000) is, like Goodnight Moon, a book whose primary intention is to put someone to sleep. (If only the more soporific titles for adults would be so honest about their intentions, aware of their powers!) It interjects what Borges dubs “partial magic” just six pages into its twenty-page length. “Some are red and some are blue,” reads the text, speaking of sleeping apparel. (An inarguable statement.) We see a bear in red pajamas, sitting and reading… Pajama Time! Not only is the front cover art represented in miniature—but so is the back, with its plug for other Boynton books, their covers rendered in correspondingly scaled miniatures. (A bunny in blue PJs perches on the chair-back, amused where the bear is anxious, its long ears waving as if in an indoor wind.)

Like the cover of Little Fur Family, with its patch of tangible belly fur, Dorothy Kunhardt’s eternal classic Pat the Bunny (1940) makes the board book experience a tactile one—indeed, that is its raison d’être. The titular hare’s hairs are soft to the touch; Daddy’s scratchy beard is an alarming amoeba of black sandpaper; you can see yourself, if woozily, in the mirror.

Our introduction to Paul and Judy, the uninteresting protagonists, lulls us into the belief that this is a didactic work: the introduction of the real world (mirror, sandpaper, flap of fabric) into the printed one suggests that texture trumps text. But Kunhardt—even more experimental than B. S. Johnson, who cut out holes in Albert Angelo—wants to have it both ways, and are we too bold in suggesting that she manages this feat? Because embedded in Pat the Bunny is another book, Judy’s Book. About an inch high, it is fixed to the larger page; the cover actually opens up, and its four Lilliputian pages tell a story (about a cat this time) even more insipid than that of Pat the Bunny.

Why, when we read Goodnight Moon, are we disturbed to see a diminished copy of an image from The Runaway Bunny? Why does Pat the Bunny’s second book make us stifle a scream? (And what is it with bunnies, anyway?) After surveying the history of stories-within-stories, plays-within-plays, maps-within-maps, Borges concluded that the fact that fictional characters can read a book introduces the frightening possibility that we are characters, being read by someone else. It’s a structural dizziness with metaphysical implications. I suggest nothing so radical. When it comes to partial magic in toddler lit, we get a tunneling sense of vertigo from seeing smaller works within the larger, from seeing real books introduced into what should be hermetically sealed worlds. This sensation speaks to the anxiety that our children—creatures of perfect simplicity—will not be able to escape the web of associations and the plague of reality-questioning that afflict the literate adult. The fix is in, even before reading truly begins.