“Errare humanum es, Dr. C.! To err is human!” the precocious boys of Crowninshield’s Academy chime, riffing off the tiny dose of Latin they’ve learned, or rather, realized they already knew. Their assignment was to find and list common Latin phrases, so that weekend found young Benjamin Franklin Pinkerton leafing through a dictionary (pausing to cautiously examine the words cir-cum-ci-sion and cop-u-la-tion) and—more prudently—spending hours at the cemetery, where a bounty of requiescat in paces and hic iacets rests.

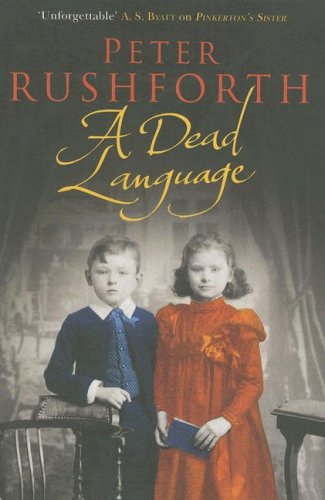

This is British novelist Peter Rushforth’s vision of prepubescent Lieutenant B. F. Pinkerton, the man who impregnates and abandons Cio-cio-san in Madame Butterfly. Ben, a slight, fair-featured boy who appears briefly in Rushforth’s previous novel Pinkerton’s Sister (2005), takes the spotlight in its sequel, A Dead Language. He’s a delightfully complex character whose stream of consciousness whips and whirls through chemistry equations, relations with effete friends and cruel father figures, and a vast inner struggle with his masculinity. He blushes easily, and his surname makes him all the more susceptible to taunting (“I think it’s Pink!” is a classmate’s usual greeting).

Pinkerton’s Sister surveyed a day of Ben’s eldest sibling—a quintessential madwoman-in-an-attic—with a style plucked from Jane Austen or the Brontë sisters. A Dead Language, in contrast, spans years and seems descended from Joyce, Woolf, and perhaps even Barthelme. These books marked a literary reawakening from Rushforth after a quarter-century hiatus from novel-writing. After publishing his first book, Kindergarten (1979), to acclaim, Rushforth spent the next decades heading a high school English department in North Yorkshire, struggling to write while teaching and administering. In 1994, friends intervened. They took him to Brazil and left him, as Rushforth told it, “on a mountain for a month with nothing to do but write.” He returned home with a draft of a novel, quit his job, and conjured a plan for the Pinkerton books. In 2005, with one published and a second drafted, Rushforth died while hiking on the Yorkshire moors.

His final work of fiction is earnest, unsettling, and supremely enjoyable. Ben’s father detests the girliness of his little boy so much that he sics a schoolteacher on him to beat out any strand of budding homosexuality. “He is blushing, isn’t he, everyone? Prettier than ever!” Mr. Rappaport taunts after accusing Ben of staining his mouth by sucking on the pen of his equally lovely friend Oliver Comstock. So it goes in Mr. Rappaport’s class, but this only intensifies our fun.

Ben has a propensity for retreating into his thoughts and memories, especially when situations get rough. Rushforth conjures his character’s inner vortex using staccato single-line bursts, lyrically stacked and often decked with parentheses. Here, heavy subjects are handled so deftly they seem playful. At times, Rushforth strikes a tone similar to the one of Arundhati Roy’s The God of Small Things. It makes you shudder and smile.

An eerie air hangs around A Dead Language. The story of Ben reminds us whom he cannot escape becoming: the lieutenant from the Puccini opera who ends up with a dead bride and a motherless half-Japanese child—a man who errs, tragically and humanly. But Rushforth has managed to stitch his story loosely enough to Butterfly to make each embellishment—any mention of Abraham Lincoln or Kate or suicide—seem fresh and incidental.