Raymond Chandler’s Philip Marlowe is malleable: literary Play-Doh for the craftily minded. As our sapient narrator, he is a lens through which we see the squalor of modern Los Angeles. We know he’s morally rigid, like an animated slab of unwritten commandments, inextirpable in his personal and political proclivities. He doesn’t take money if he finds a job unethical; he doesn’t respect corrupt police or politicians, regardless of their motivations; he doesn’t sympathize with drunks or wife-beaters; he doesn’t like the rich but he doesn’t weep for the poor. He’s a well-worn scourge of complications and intricacies, his own Osiris.

Howard Hawks and William Faulkner gracefully and loyally translated Marlowe to the screen for The Big Sleep, just seven years after the novel’s initial publication. By 1946, Chandler’s books were growing in stature, and American cinema was suffused with film noir, so the character was already relevant; he didn’t need to be modified. By 1973, though, Marlowe and his hard-boiled kin were forgotten, irrelevant, so naturalist auteur Robert Altman had a few changes to make. If Hawks’s Big Sleep is the archetypal faithful Marlowe film, Altman’s adaptation of The Long Goodbye is the archetypal modification: characteristically syncopated and opaque, both satire and homage, poison love letter to a genre and inside joke to its enthusiasts.

Chandler’s Marlowe thinks fast, talks faster, takes a punch like a champ. He’s invidious, antagonizing authority figures into socking him; once he sees how they throw a hook, they don’t get the chance to land a second. Altman’s Marlowe wears wide lapels and talks to his cat. He ponders his own sad, solipsistic musings because no one else will. He’s out of touch, out of his element, caught in the slipstream of modernity. Altman steeps him in voyeuristic discomfort, the camera drifting and floating and suddenly zooming, never content to stay still. The camera’s constant activity underscores Marlowe’s desuetude, makes him even more pitiable.

The Long Goodbye, Chandler’s longest and deepest novel, dissects the life of a private eye: the boring parts, the tormenting parts, everything in between. It’s more social commentary than noir, with a thread of dubious mystery holding the narrative together. Corruption, sinisterly sunny L.A., big men throwing their meaty bellies around, slamming hairy knuckles on desks, pounding shots of cheap whiskey to

euthanize the slivers of passing morality. Marlowe is our tour guide on a joyless ride through the American dream as sordid reality. Sketch and scuzz are ubiquitous in Chandler’s L.A., and Marlowe is not a bright, shining light: he’s part of the city, one of its fleshy appendages who just happens to rebel a little more than most.

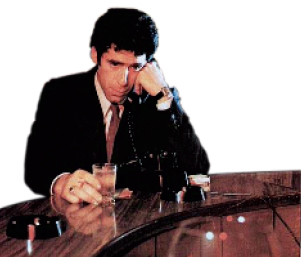

Altman takes Marlowe, Sherlock of the noir age, and cruelly drops him into California circa 1973. In the role, Elliott Gould possesses an air of otherness: he’s pathetically paranoid, a moke susceptible to life’s aleatory afflictions, like the mean streets have chewed him up and spat him out. His outdated wisecracks go over the heads of the police; he sucks down cigarettes while the spandex-clad ladies next door succumb to fleeting health crazes. Most jarring to viewers, Gould doesn’t look like, doesn’t sound like, doesn’t act like, doesn’t possess the authoritative suavity of Humphrey Bogart. Bogie was Philip Marlowe, setting the standard for detectives the way Sean Connery set the standard for spies. You never suspected Bogart might take a bullet to the gut, or fail to solve whatever convoluted case had fallen into his lap. By comparison, Gould’s performance is subtle and not very attractive. Bogart was a loner; Gould is lonely.

People found Gould to be an awkward and unbelievable Marlowe. They were right: he is an awkward and unbelievable Marlowe, and that’s why The Long Goodbye works so well as an introspective, almost satirical take on Chandler’s anti-hero. A year before Roman Polanski and Robert Towne momentarily rejuvenated noir with the wickedly intelligent Chinatown, Altman showed audiences in post-Vietnam/Watergate America how outdated the masculine hero of The Big Sleep or The Maltese Falcon had become. The morally admirable, contrarian avenger was something Americans needed, but something we didn’t want.