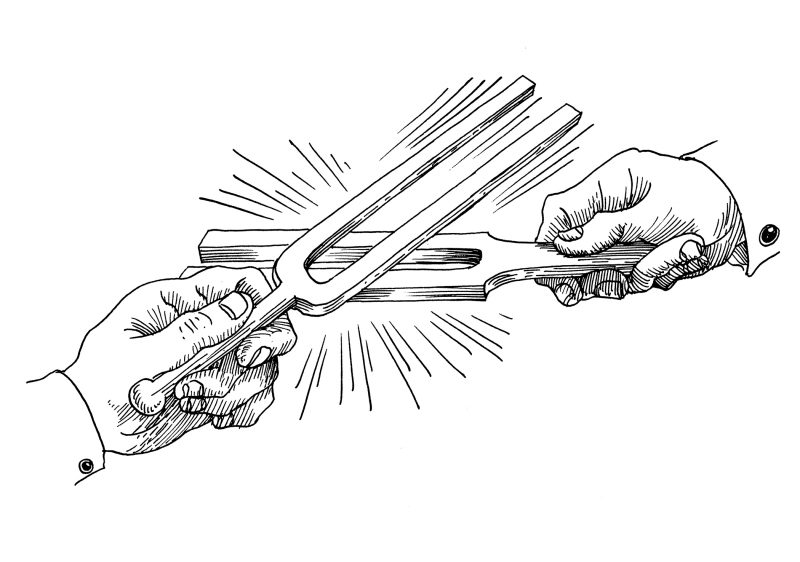

In 1988, more than a dozen of opera’s greatest superstars—including Plácido Domingo, Luciano Pavarotti, and Birgit Nilsson—added their names to a petition before the Italian government, asking it to lower the standard pitch at which all orchestras are tuned. At the time, international standard pitch was set at 440 Hz, which is to say that the A above middle C should be tuned to resonate at 440 cycles per second. The petition asked the government to lower this to 432 Hz, claiming that “the continual raising of pitch for orchestras provokes serious damage to singers, who are forced to adapt to different tunings from one concert hall or opera to the next,” and that “the high standard pitch is one of the main reasons for the crisis in singing, that has given rise to ‘hybrid’ voices unable to perform the repertoire assigned to them.” The petition ended with a demand that “the Ministries of Education, Arts and Culture, and Entertainment accept and adopt the normal standard pitch of A=432 for all music institutions and opera houses, such that it becomes the official Italian standard pitch, and, very soon, the official standard pitch universally.”

Clearly, the vocalists who’d signed this petition were exercised over something. Among the most strident critics at the time was the Italian soprano Renata Tebaldi, who spoke at a conference on the subject of musical pitch that same year. “Why should the color of the mezzo-soprano voice suddenly have disappeared off the face of the earth?” she demanded to know. “Why do we no longer have baritones who sing by unfurling and broadening out their voices? The basso profundo has disappeared; to find a Sparafucile to play in Rigoletto is impossible. Voices are now used that perhaps can sing low but have no body. They don’t say anything.”

The petition had its origins in one of the strangest conflicts to have overtaken classical music in the past thirty years, and many of the luminaries who signed it were completely unaware of what they’d gotten themselves into. The sponsor of both the petition and the conference that featured Tebaldi was an organization called the Schiller Institute, dedicated to, among other things, lowering standard musical pitch. At the time, the New York Times identified it as “an organization that promotes a strong alliance between the United States and Western Europe”; its website defines the organization as working to “defend the rights of all humanity to progress—material, moral and intellectual.”

But behind this respectable front lurks a strange mélange of conspiracy, demagoguery, and cultish behavior. At its founding, in 1984, its then chairman, Helga Zepp-LaRouche, laid out the institute’s role in surprisingly apocalyptic...

You have reached your article limit

Sign up for a digital subscription and continue reading all new issues, plus our entire archives, for just $1.50/month.

Already a subscriber? Sign in