FEATURES:

- Spartan rooms

- A writerly legacy

- A military legacy

- Cold pineapple juice

When it opened its doors for the first time some seventy years ago, the Atlanta Hotel was the first hostelry in Bangkok with a swimming pool. It might also have been the first to later ban sex tourists: a quietly aggressive sign by the front door, placed there in 2002, states: sex tourists not welcome.

In the 1960s and ’70s, the hotel was a gathering place for writers and artists. It was also popular with US military brass and others passing through as part of the war effort. It was during these years that Bangkok’s well-known sex trade exploded, and the Atlanta seemed destined to be sucked permanently into that culture.

The Atlanta is the legacy of the Henn family—the father, Max Henn, fled Nazi Germany, and in 1952 he wound up in Thailand, where he started a pharmaceutical lab that sold cobra venom to the United States. He fell in love with a Thai chemist who worked in the lab, Mukda Buresbamrungkarn, and they married and had a son, Charles Henn. But the venom lab did not thrive, so to make ends meet, Max converted rooms at the lab’s offices into accommodations. He was, apparently, a reluctant hotelier.

When the Henns divorced, the hotel was left to Mukda’s family to manage. It fell into disrepair, but the Henns retained ownership. The Atlanta devolved over the years into a seedy joint that catered to those frequenting the nearby notorious red-light districts along Sukhumvit Road, Soi Cowboy, and Nana Plaza, go-go bars packed with young Thai women and men, many dressed in costumes, naughty schoolchildren, and so on.

But the story took a surprising turn. In the late 1980s, the Atlanta was re-embraced by Charles, who had been sent away to Oxford and Cambridge for school when his parents divorced. Max and Mukda had then pursued their own lives and careers away from the hotel and Thailand. The revived Atlanta was once again popular among writers and artists such as Elizabeth Gilbert, who stayed there on her Eat, Pray, Love tour. And unlike other “writers’ hotels” such as the Ritz in Paris, this was one that a writer could actually afford.

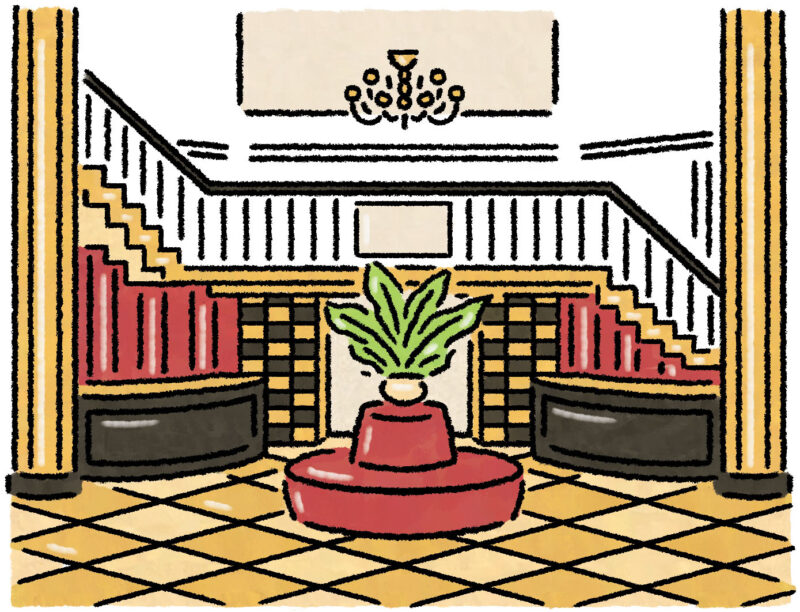

When I visited, in October 2022, the hotel was emerging from Thailand’s COVID pandemic restrictions. Its “soft opening” was geared toward returning guests and friends of returning guests (I had stayed there in the early 2000s and had also lived in Bangkok as a journalist for two stints). As I arrived, a liveried doorman greeted this traveler, swinging open the wood-framed glass doors to reveal the original, largely untouched art deco lobby.

This is the Atlanta. In the cotton-candy-pink and red-vinyl mid-century café, a Dutch family and scattered solo travelers tuck into an array of Thai dishes and Thai coffees, alongside eggs and toast and cappuccinos. A cold glass of fresh pineapple juice arrives at reception on a small silver tray, and I am told by the cheerful desk clerks to “not rush. Sit, please,” as they carry the tray to a soft sofa. The staff is just as gracious and kind as I recalled. The floors gleam. The stacks of atlanta notepaper and pencils are ready for me to jot down thoughts. In addition to a cozy writers’ nook with rolltop desks, the lobby offers a sixteen-page booklet that provides advice on haggling, hailing taxis, cleanliness, and appropriate attire for visiting Buddhist shrines.

The rooms and suites remain Spartan, with all the trappings of a solid budget hotel, from the scratchy towels to the tiny packets of dandruff shampoo. But each has been freshly painted and new drapes have been hung. The vinyl floors are impeccable and the tiled bathrooms spotless. And there is still the pool. Across the open-air lobby, the gardens give way to the large swimming pool and smaller ponds, where the resident tortoise community lounges in the shade. Toward the end of a day, after taking in wats and shops in Bangkok, I can be found here.