Once, not knowing a word of German, I ventured inside a nightclub off the Kurfürstendamm in pursuit of some simulacrum, perhaps, of Berlin Stories. A man in a housecoat and hair rollers was lecturing the audience, a preponderance of which were heavyset, leather-clad, and drinking something orange, like astronaut juice. They were roaring in appreciation, and I, Germanless, despaired. Soon, though, he was replaced by another act which needed no translation. He—she—waltzed onto the stage in drag, but this one wore a dirndl, hair in two long black braids. As her red bow lips broke into tremulous song, she tossed flowers into the audience from a basket on her arm. I never discovered the name of the song, or anything else about the act, but in the unreal pink light, I realized that this was what I was looking for: the eerie but pleasant sensation of false déjà vu; an artifice so genuine that you couldn’t call it revival. It was channeling.

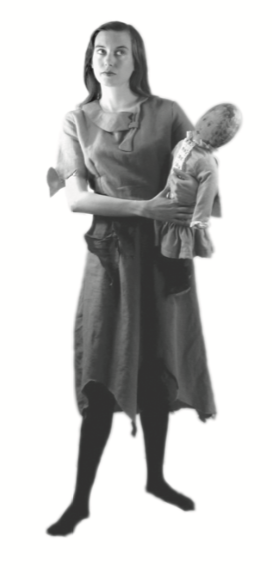

I didn’t think I would ever experience anything like it again, until I saw Bree Benton perform as “Poor Baby Bree” in her show Weary River last December, at Don’t Tell Mama on West 46th Street. In a distressed frock and shawl, sans makeup, Bree sauntered through the crowd and made her way onstage with a hobo’s bindle; she opened with “Weary River” (from the 1929 early sound film) accompanied by her partner Franklin Bruno (of Nothing Painted Blue) on piano:

I have been just like a weary river

That keeps winding endlessly.

Fate has been a very cheerful giver

To most everyone but me.

Oh, how long it took me to learn

Hope is strong and tides have to turn.

And now I know that every weary river

Someday meets the sea.

Then she segued into “If the Rest of the World Don’t Want You (Go Back to Your Mother and Dad)” (1923). Cycling from melodrama to farce and back again, the songs and recitatives were artfully curated for effect: they told story after story of waifdom and heartbreak, from the doll who died in surgery (“I’ve Got a Pain in My Sawdust,” 1909) to the little girl kidnapped for ransom (“Oh! Take Me to My Mama Dear,” 1903) to the jailed mother giving up her three-year-old to the orphan asylum (“Little Pal,” 1929).

“Oh, I do so like stories!” Bree exclaimed halfway through her medley of gumption and woe. “Though they can be awfully sad.” She did not smile.

Lots of women have style; Bree Benton has an aesthetic. Born and raised in L.A. with a ’70s starlet for a mother, she might have parlayed her background, and her beauty, into a conventional acting career. Instead, she gravitated to obscure vaudeville, music hall, and parlor songs, the stuff of sheet-music aficionados. (The tag line for her show read, “From the dusty shelves of the old booksellers; from the graveyards of dealers in antiques and junk; and from the once-glittering movie palaces, now stained and crumbling, come the words and music… of Poor Baby Bree.”) This aesthetic is what gives her performance its comic delicacy: lines like “Still, don’t curse the day you came on this earth / But think of the woman who gave you birth / And the man that fathered you when just a lad” are light as aquarelles. One is hard pressed to mock these sentimental songs—Bree’s tête-à-têtes with her rag doll suddenly illuminate the possibility that it is the song itself, this neglected, tatterdemalion thing, that she is addressing with such affection.

Poor little songs, plucked from obscurity only to fade away! As the night wound down, Bree placed a basket on her arm and started tossing flowers into the audience. It was the Berlin cabaret all over again, and this time, as she launched into the 1931 ditty “I’ll Pin Another Petal on the Daisy,” I understood every word.

—Ange Mlinko