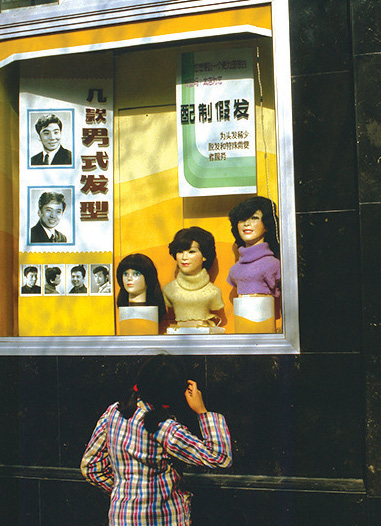

A fertile fashion breeding ground consists of social pulls and tugs: the need to belong, the need to break free; the urge to disappear, the desire to be seen. In the years following the death of Mao Zedong, when China commenced one of the most extreme fashion transformations in history—from collective, state-produced attire to the label-glamor of global pop-consumerism in less than two generations—these tensions were manifold. “People in reform-era China [1976–89] wanted to be citizens of the world,” writes material-culture historian Antonia Finnane. They also wanted to escape from years of mass identity and become individuals: “There was this deep hunger to do something among youth that would express a little bit of… individual rebellions, self-expression, and to be cool,” says journalist and China scholar Orville Schell, who has been splitting his time between China and the United States since 1975.

The first indications of the consumer culture and brand prominence that exist in China today (the country has been the world’s second-biggest consumer economy since 2013, spending $3.3 trillion in private consumption) can be found in the turmoil, confusion, influences, and uncanny fashions of those reform years. Then, as now, it was the emotional impact of fashion, the charged unsteadiness of the possibility for new identities, that electrified the air.

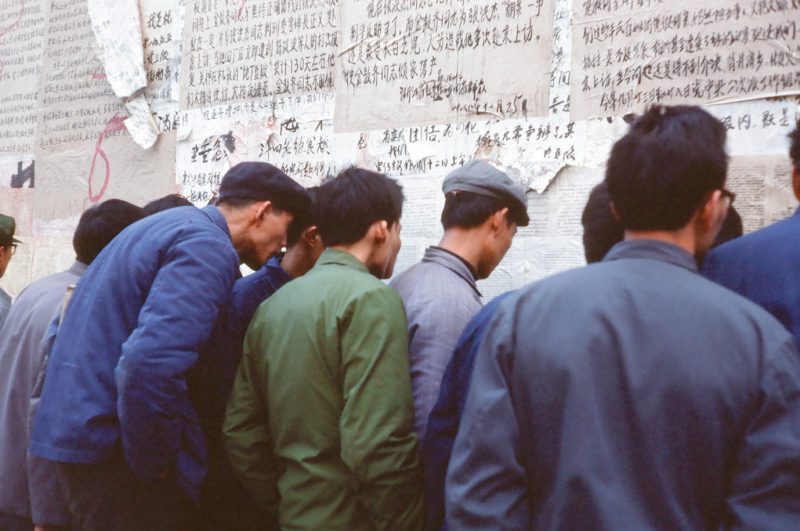

Let us set the scene as turmoil begins in 1966. Mao is reinvigorating his campaign of permanent revolution, and has called for the purge of all things old-minded (that is, Confucian and feudalistic), as well as anything foreign or bourgeois. Chinese fashion quickly reduces to “three old styles” (lao san zhuang) in “three old colors” (lao san se), but the emotional impact, political implications, and physical repercussions of clothing skyrocket. Contrary to popular Western belief, the iconic square-cut and unisexual uniforms of Chinese communism—the “Mao suit,” the youth jacket, the military coat, all in drab grays and whites and blues, with the occasional, coveted army green—are not outright mandated by the party; rather, they are unwritten and spontaneous responses to anti-bourgeois sentiments, military propaganda, revolutionary fervor, communist ideals, social pressures, and personal beliefs. Clothes can show allegiance or disguise it; they can help the wearer wield power or relinquish it, hold her head high, or avoid getting her nose shoved into the dirt.

The Red Guards, legions of revolutionary students sporting red armbands, take it upon themselves to “destroy the old and establish the new,” the Peking Review (later called the Beijing Review) announces in September of 1966. These youths, with Mao’s blessing, are effectively above the law, and over the next decade the...

You have reached your article limit

Sign up for a digital subscription and continue reading all new issues, plus our entire archives, for just $1.50/month.

Already a subscriber? Sign in