Dismiss me as a philistine, but it seems to me the aesthetic claim of the movie poster as art object is pretty easy to make, easy to love, and easy to summarize. Though they are industrial images produced by marketing departments and intended only for sales purposes, they are full-throated singings of the folk ballad of cinema, of alternative-universe thrills and swoons and transportations. But they perform this function inadequately, at a poignant remove, stuck expressing its obsolete present moment like a drifting radio signal. A poster’s commercial purposes are instantly transmuted, upon creation, into an evocation of another, otherworldly experience—they’re the Transfiguration icons daring to literalize in purely symbolic terms the supernatural emotionalism of movies. Not a good film or a bad film, but the basic, plastic, semiconscious there-ness of movies. Will you share the epiphanic bliss a poster promises, or will its holiness fail to touch you? They are devotion, but also evangelism. The essentiality of such a poster is not representation of something else, nor is it, completely, “the thing itself”; rather, it is a mysterious third path, a never-ending dialogue between the film, the image, the pitch, our hopes, and our memories. Posters are modest, they are not the product of an artist’s hermetic purpose, they are reproduced works visually consumed by us as a society, rather than merely by single art-appreciators or collectors. They are an explicit expression of a universal yet mythic past, although they seek—often unsuccessfully, also poignantly—to sublimate themselves in favor of the movies they glorify. Mad for their generous personality and their intimate relationship with the culture to which they speak, I’d rather look at movie posters than original artwork, ancient or contemporary. Sometimes, I prefer the poster to its film.

The “schools” of “one-sheet” posters have, of course, varied by era and by country: the diagonal-blitz screaming-tabloid design of the American ’40s and ’50s, the jelly-bean-colored-and-patterned chaos of the late-century Japanese, the fluorescent romance-paperback tableaux of contemporary Bollywood, and so on. To what degree a poster’s orthodox adherence to the tastelessness and shrillness endemic to the form disturbs you is a strictly personal matter; I, for instance, have no great love for the Hollywood monster-movie posters of the mid-century, but will fall into a swoon for a Mexican wrestling-monster poster twice as loud and crude. Often, an element of demented mystery is the entrancement—as if some posters extol the virtues of crazy movies that do not exist, or would not in a sane world.

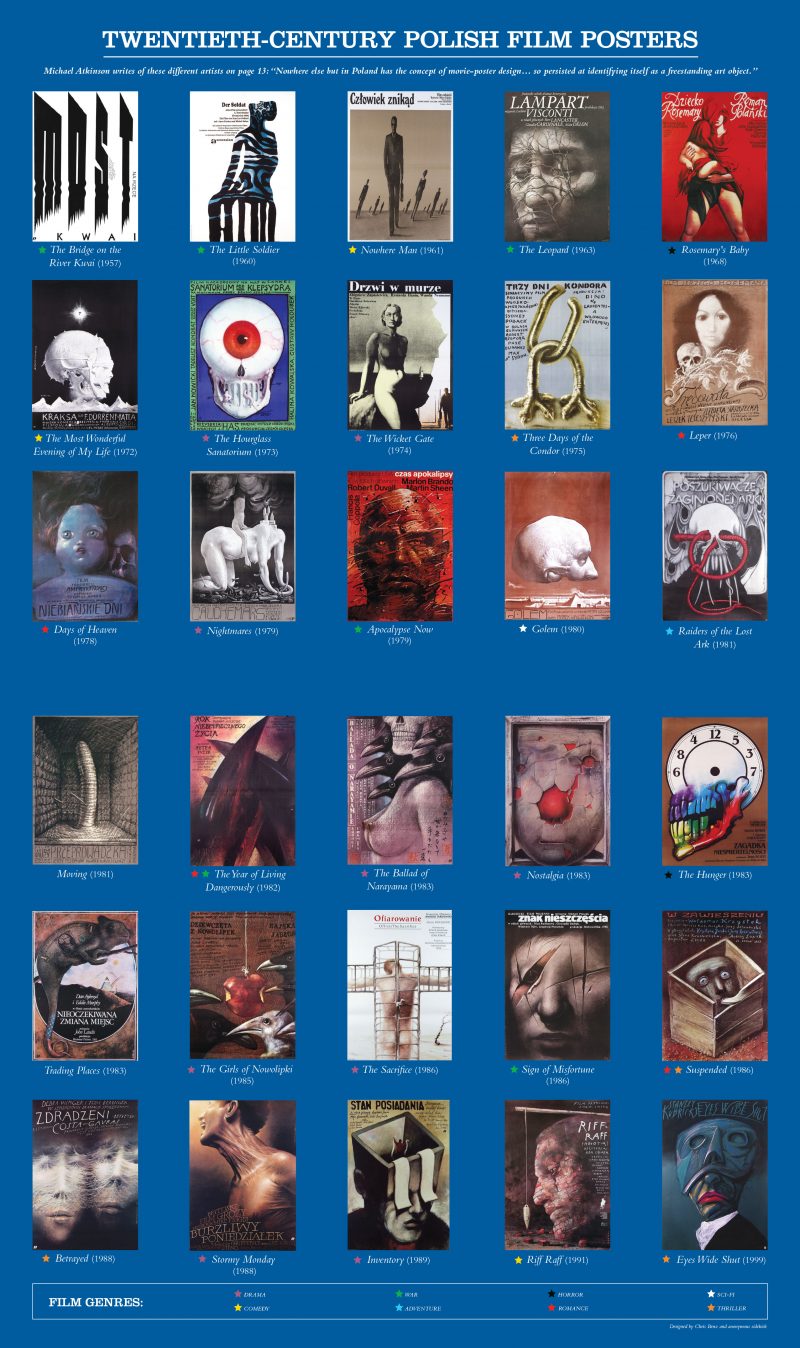

Pulp form, thumbnail allusiveness, hyperbole, uncouth syntax—this much we all understand about movie posters, truly a public art form only Papuan tribesmen could claim to be ignorant of. Until we go to Poland. Outside of its fevered circle of cultists, the authentic phenomenon of Polish movie posters remains one of the great secrets of twentieth-century pop art. There are large-format books published here showcasing Italian movie art, Japanese posters, American exploitation graphics (no shortage of these), and, remarkably, amateur posters for Hollywood films made by Ghanaian artists on secondhand flour sacks. But none of the Polish. Nowhere else but in Poland has the very concept of movie-poster design gotten such a radical overhaul, and nowhere else has it so persisted at identifying itself as a freestanding object. The primary philosophical singularity at work in the tradition of Polish movie posters going back at least to the ’50s is this: The poster art need not visually suggest the movie in question in any concrete way whatsoever. In fact, direct visual reference to anything in the film is often shunned. The poster should at most semiconsciously evoke the thematic feeling of the movie (or its title—in many instances, Polish posters seem to be created with abject ignorance of the cinematic work itself). The artists chosen are prized for their intensely idiosyncratic visions, to which the movie-poster form and the marketing exigencies of a particular film must defer, not vice versa. (Many of the artists have become famous in Europe, and a few, including Jan Lenica and Lech Majewski, have gone on to make films.) Since the majority of films made and seen in Poland in the postwar period were released by Film Polski and ZRF (Zespoly Rozpowszechniania Filmow, later simply Polfilm), this daring aesthetic stance seems to have been institutional as well as cultural.

Pick any example: say, the Polish poster for Luis Buñuel’s 1974 skit-satire masterpiece The Phantom of Liberty, painted by Wieslaw Walkuski. The film is a busy, buoyant surrealist comedy of manners and norms, skewering bourgeois conventions and priorities, starring a battery of Euro-stars (Monica Vitti, Jean-Claude Brialy, Michel Piccoli, etc.), and shot in Buñuel’s uninflected broad-daylight late style. But Walkuski’s lavishly executed, vividly figurative painting is a dark slice of inexplicable nightmare: a giant feminine visage bronzed or atrophied into a statuesque state of decay, its single eye mummified, its left side putrefying and skeletonizing into stretched shreds of tissue, through and behind which we can see a soft blaze of amber sky, perhaps, or sunset storm-light, or something. What the? Whatever questions we might feel instantly compelled to ask die in our throats: clearly, what we thought we knew about posters, movies, etc., no longer applies reflexively, with a broad brush. Is this an ad for a movie, or is it something else entirely? There’s no reason to suspect that Walkuski saw Buñuel’s film; indeed, given the assignment’s result, you could surmise that it was agreed he shouldn’t. Look at it again: We cannot, really, imagine the path of creative or business choices that led to this final product. It is a closed circle. (As is often the case on Polish posters, the hand-scrawled title and credits are stuffed around the border edges, an afterthought.) Walkuski’s canvas is an eye-seizing monster on its own, but as a movie poster it acquires a secondary vein of significance—its accord with Buñuel is indecipherable but not necessarily absent, and thus between the two artworks lies a secret, and an implicit expansion of the signifying range of both. That secret is the final-dominion realm of Polish-movie-poster art, the shadowy, lonely place where each of us arrives at our experiences of arcana, visual pleasure, and art-consuming empathy alone and naked, no matter how public the medium. You could say, more simply, that Walkuski conjured a second movie from the living brain of the first, and made it completely his own.

The Polish movie poster represents by itself the modernist revolution the medium otherwise never had—and has sustained that revolution for over five decades, irrespective of fads or progressive styles or the demands of salesmanship. This latter point is questionable, of course, once you consider how the posters were meant to work as promotional tools, and to whom they were pitched. These are questions to which I have no good answers—perhaps Poles have simply been more demanding of their ad culture than we are, and more sophisticated about the relationship between advertising and art. (Instead of Warhol-ishly making art more ad-ish, the Poles made their ads artier, and it’s difficult not to appreciate the difference.) However you read it, the fact that Poland, even (or especially!) during the Iron Curtain years, embraced this sort of confrontational, unpredictably allegorical, often experimental image-making as ordinary street decor and movie-house advertising makes that proud and beleaguered nation look like some kind of bohemian nirvana, a paradise where the proletariat grew up fat on the unskimmed cream of modernism.

In a sense this is true, at least to the extent that Poles would be shrugging, now or in eras past, about any astonishment we may have over what they’ve long treasured as a staple of their creative identity. Imaginatively designed poster art, remember, for operas or liquor or travel or table grapes, was a universal part of the scenery in first- and second-world cultures running back into the nineteenth century. Come the world wars, it became less so in America, but in Europe the elliptically designed poster remained a lingua franca, a situation only exploded out by various fascist and communist regimes, who fastidiously exploited every opportunity for propaganda. The Soviets in particular, absorbing the futurists and folding them into the evolution of socialist realism, made great use of the modern poster’s capacity for muscular shorthand imagery, perhaps peaking with the romantic eloquence in the agitprop posters they helped fashion for the Spanish Civil War. The official Polish visual tradition up to that point had been dominated by various schools of Postimpressionism and Expressionism, with very little unborrowed from other countries’ traditions. But the folk-art heritages—the elaborate wycinanki paper-cutting ornamentations, the carved-and-painted linden sculptures, etc.—are more telling, and had their own hit-you-in-the-eye effect on the various Polish avant-gardes (among them, photomontage) that fought for supremacy in the early century.

In the postwar years, Stalinist homogeneity threatened to swallow the landscape, but then, as legend has it, a young designer named Henryk Tomaszewski, who died in 2005 at ninety-one, was asked in the years immediately after World War II to create posters for the flood of Hollywood films then washing into the newly opened markets. The cities were in rubble, and miles of fencing surrounded the ruins, waiting to be dressed. Tomaszewski and his cohorts were insistent on making their spare, allusive posters unique, not in direct imitation of their American counterparts, despite the new authorities’ suspicion that average Poles would not fathom the abstracted, semi-surrealist images. Hungry for escape and news of the world, Poles went to the movies in droves anyway, and the progressive Polish poster agenda continued organically. (Paper cut-out collage and photomontage were always go-to techniques.) By the ’60s there were hugely successful biennials and poster-art schools, and however un-communist much of the art seemed, it had become an unpurgeable facet of the culture.

It was when the posters evolved away from Tomaszewski’s sprightly, cartoonish figurations and toward a brooding, existentialist palette that the nation’s “wall and board” genre started to become world famous. (And these were not merely movie posters but promotional artwork for festivals, plays, circuses, governmental programs, concerts, even gallery retrospectives of other, very different artists.) Generally, design is a manifest frame of mind—the lovable old international travel poster from the ’20s to the ’50s is nothing if not a utopian summoning of peace and fun and wonderment. But while the Polish posters of the ’60s and beyond may or may not have been trying to evoke, however obliquely, the tortured dramatic soul of a particular movie, they are helplessly coalescing a mass statement about life under communist rule. It is unmissable and predictable: as the new generations of artists rose up into the field, born during or after the war and facing the best years of their lives beneath a permanent thunderhead of oppression, censorship, bread lines, and surveillance, the poster art they created grew fiercer and darker and more outrageous, and its bitter public grew ever more devoted.

Strangely, extolments of Polish poster design rarely if ever mention this obvious subtext—the public form reflecting the public sphere, expressing its psychosocial angst in stark ways the state can neither ignore nor mitigate. The posters—particularly those by Walkuski, Majewski, Franciszek Starowieyski, Wiktor Sadowski, Andrzej Pagowski, Stasys Eidrigevicius, Mieczyslaw Gorowski, Romuald Socha, and Waldemar Swierzy—came to embrace a kind of ur-Kafka-ness, a lightless Mitteleuropean netherworld stalked by Schulzian figures twisted in all sorts of metaphoric knots by frustration and fear. Bosch is another common avatar, used for tone as well as totem figures (the Poles are fascinated by man-birds), as is Magritte—but with the Belgian’s neutral irony wrenched down to a subterranean wail. The influence of various symbolists, particularly Odilon Redon, is also evident. The painfully irrational is paramount—and for public artwork executed in the nonsensical, Kafkaesque maze of totalitarianism, it makes perfect sense not to directly reference the movie at hand. Why honor the myth of logic? Surrealism had at last found its most relevant social context.

Take, say, the fairly banal and streetwise little Dustin Hoffman crime drama Straight Time (Polish release, 1980), whose Majewski poster features a woman’s face with stretching angel wings jutting out of her eye sockets, flanked by tiny mouths emitting a snake and a coin. Or homeboy Krzysztof Kie´slowski’s widow’s-grief-during-martial-law art film No End (1985), the Pagowski image for which is no more than a giant safety pin graduating into a spinal column and bare skull at its head—in either or nearly any case, the art itself, using its own chosen battery of motifs and brooding metaphors, makes a vivid statement about the world in which these movies find themselves.

The shock of the deranged image; the lurid metaphors for entrapment and political claustrophobia; the endless shadows from which creep some tortured knot of agony; the moldy, smoggy sense of police-state depression, the inexhaustible symbolic mutation of the human face (eyes and mouths replaced by each other, and by animals and symbolic objects, ad infinitum)—this is the syntax on the Warsaw walls during the Eastern Bloc years, and since, regardless of what was showing at the Bijou. Sometimes the posters retained Tomaszewski’s bold-colored graphic-cartooning style, but the upshot can be just as unsettling, as with Eryk Lipinski’s 1976 poster for the dire 1973 Elizabeth Taylor suspenser Night Watch, composed entirely of a broadly drawn, hairless, sexless, crying face, white and flatly throwing droplets as if it were made of milk, noseless (a prophecy of Taylor buddy Michael Jackson?), and quite evidently a derisive swipe at Taylor’s aging movie-star profile, all pleading eyes and melodramatic keening. Is this a movie poster that lays satiric waste to its own movie? There’s no mistaking it, I think: the Polish poster form attained such an independence from its own marketing definitions that the artists were free to make their own critical revelations about the film in question, or its star, or film in general, or anything at all.

Often enough, the departures the artists make can leave you gasping: Walkuski’s painterly vision of shadowy faces consumed by white webbing, for Costa-Gavras’s KKK romance-drama Betrayed (1988); Marek Ploza-Dolinski’s harebrained poster for the muddled, “international” corporate intrigue picture The Concorde Affair (1979), which juxtaposes an Uncle Sam top hat against a figure in ornate dress armor, topped with the head of a braying fruit bat; Janusz Oblucki’s riff on Trading Places (1983), which at least employs the iconography of the U.S. dollar, but otherwise invents an old-world tableau—a giant chameleon (with George Washington highlighting his midsection scales, and Old Glory patterns on his tail) framing a window looking out onto a primeval mountainscape peaked with the E Pluribus Unum pyramid and rainbow. Indeed, it does seem that the extraordinary imagination poured into Polish movie posters could act, just in a pedestrian sense, as overhype—did audiences ever get disappointed with the relatively prosaic films? Looking at, say, Walkuski’s image for Mike Figgis’s thriller Stormy Monday (1988)—a raw, pulsing study of a screaming, distended masculine figure’s popping veins and stretching skin—you can’t help but wonder how many Poles were expecting, from the movie, something a little more strenuous. It’s hard to imagine that Jakub Erol’s cold, Lovecraftian design for Raiders of the Lost Ark (Polish release 1983), complete with fanged skull, vaguely vaginal catacombs, and a red whip that could easily be mistaken for a giant worm, didn’t keep a certain number of ticket-buyers away from that populist party-movie. It seems not to have mattered, across the board. Which is the most hopeful manner in which to read this beautiful cultural syndrome: as an unequivocal, and still persistent, triumph of art over commerce, of painting and vision over the bottom line that controls so much of film culture and the art world. This beats the Warhol concept dead flat. The Polish movie poster isn’t merely a successfully aestheticized commercial product—it’s the exultant instance in which a commercial form has been entirely redefined as purely aesthetic. It’s not “repurposing,” but reincarnation. It’s the secret path to a new and braver world.