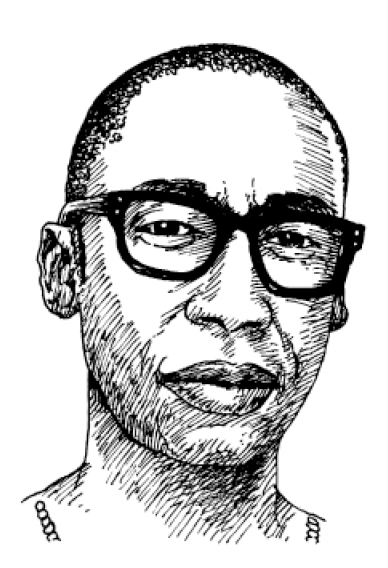

As legend has it, Hollywood is named after the wood of a witch’s wand that in one flick of the wrist could conjure anything one wished for. In the midst of the mysticism, magic, and allure of that place is Raphael Saadiq, who, after warning me of the story’s apocryphal origins, told me the tale of “holly wood.” It’s fair to say that his success is a product of his own toil, not of some metaphorical magic fairy dust or wand waving. The Grammy-winning, Oscar-nominated impresario is one of the music industry’s most pragmatic, relentlessly hardworking, multi-hyphenate talents, a man more likely to appear in the credits of your favorite’s album than on social media. Saadiq, a Taurus (naturally) and an Oakland, California, native, now lives and works in Los Angeles. Though he’s been a fixture in popular music for almost three decades, many people don’t know Saadiq beyond how he makes them feel.

The ’90s was the era of his hit group Tony! Toni! Toné!, which gave the world “Feels Good,” the intimate “(Lay Your Head on My) Pillow,” and “Anniversary,” a yearly reminder to celebrate love. Fast-forward to Y2K, when people were losing their shit over the potential end of computers, and his new band Lucy Pearl gave us the space to put on our studded denim jackets and new kicks and entertain the idea of getting freaky while we “Dance Tonight.” In addition to making the solo classics “Ask of You,” “Good Man,” and “Be Here,” he penned and collaborated on hits for greats such as Whitney Houston and D’Angelo, contemporary hit-makers like Rick Ross and, more recently, the visionary Solange, executive-producing her Grammy Award–winning album A Seat at the Table, and helping to make its venerated single “Cranes in the Sky.” In early 2018, “Mighty River,” a song he cowrote and coproduced for the film Mudbound, was nominated for an Academy Award for Best Original Song.

Although his musical credentials are well-known, there was still much to learn about beyond Saadiq’s mystique. I assumed our interview would take place between quite a few press obligations leading up to the release of his new project. As I prepared for the interview call with the quiet legend, I wondered how much he’d be willing to divulge. In an age that favors perception over reality, how has Saadiq seemingly managed to retain a sense of normalcy, humanity, and even secrecy in an industry that doesn’t openly reward such noble traits? Fifteen minutes into our conversation, Saadiq answered my overarching question. With humor and candor, he shared with me stories of his childhood, the lingering trauma of family deaths, his individual spirituality, the masks his “happy music” allows him to wear, and which artist has challenged him the most musically. He even opened up about the personal sacrifices he’s made in order to be Raphael Saadiq. Despite his many accomplishments, he prefers to be a guy who can walk among the trees.

—Elise R. Peterson

I. Test Crashes

THE BELIEVER: Is music where you allow yourself to be the most vulnerable?

RAPHAEL SAADIQ: Yeah. I’ve been married to music probably my whole life. It’s been the one common thread in my life [and] was my meditation before I could actually meditate. It was the thing I could run to when my sister was killed in a car accident or when my brother OD’d and my other brother killed himself. It was the thing I could go to, and it would heal me faster than anything. I realized later on that [it] was the thing that helped me out through different struggles, ups and downs in the industry, dealing with things like bad accountants, bad management, bad group breakups. But you’d never see it, because I don’t really show emotion like that, but I do get mad a little bit. One of my last struggles with management, I feel like God sent different things to happen musically for me. Like Kendrick, when he wrote, “Nigga, we gon’ be alright.” I used to drive from LA when I was going through something, [and I’d] put that on. If that record hadn’t come out, I think I would’ve hurt somebody.

BLVR: Isn’t it incredible what music can do? I mean, I could say the same thing. And now we’ve seen Kendrick win a Pulitzer for Damn. So many of us didn’t even realize that someone could win a Pulitzer for an album, especially for a hip-hop album. What do you think that did to open up doors for songwriters like yourself? Where can songwriting go now?

RS: Honestly, I think it’s amazing that he won, but he’d already won. That award is cool, but he’s way bigger than any award. [The award] is to let the masses see what it could do. I think I texted him when To Pimp a Butterfly came out, and I said, “Hey, man, thanks for taking one for the team, because you didn’t have to do that.” He didn’t really have to take a risk on making music like that in today’s era. Every once in a while, somebody comes up to take one for the team and they do well. I’m just glad that that generation has a vocal, conscious person who can say a lot of things very fast but is very meaningful to everybody. That record is an ancestor type of joint. When I heard, “We gon’ be alright,” I had to just go with that; I had to believe that.

BLVR: I absolutely feel where you’re coming from. So many people can relate to that record on so many levels, from black people to creatives. I think for me, living in New York and being a creative person, it is taxing, and you have to be committed to your art. So hearing another artist say, “Nah, you’re gonna be all right; you’ll be good”—sometimes that’s all you need to keep the fuel going. Why do you think you repress emotions?

RS: I think mainly because my first brother died when I was seven. It sort of stuck with me, and after that it was hard for me to be close to people. I’d lost so many people in that fifteen-year run that I just got really hard. I just lived inside of music. So all the things was happening, and I was writing music that was very happy—“It Never Rains,” “Anniversary,” “Just Me and You.” I was really writing music for myself, to make my own self-therapy.

I grew up watching the stars from the ’60s get into the light in the ’70s, like Michael, Prince. A lot of these rock-star cats would get hooked on drugs. People I love, who I actually wish I could be around now, are kind of gone. But I got a chance to go hang out with and talk to Michael and I got a lot of time with Prince. I would [have] loved to [have sat] with Marvin Gaye, but I feel like the industry destroyed them. Drugs destroyed their minds, because it’s a lot to deal with.

Earlier on we could look back and see what it was. You know, you live in LA, you got palm trees, Bentleys, girls jumping around butt-ass naked. It’s a whole lot, and a mind sometimes can’t deal with it, because it’s tired, and then the next thing, somebody wants to introduce you to drugs. And you think it’s cool because somebody else did it. Jimi Hendrix did dope, so he might’ve been doing some drugs to get to this different level, so you want to get to that level. Or you wanna be like Sly—I love Sly—but for me that just wasn’t winning. So to me they were sort of like the crash test—the people that were the test, and the people who went through all the things that we can actually sit back and look at and say, OK, do we really want to go down that road? Do I really want to be somewhere where I can’t go outside? Or do I really want to hide behind gates to live?

BLVR: That’s not living.

RS: I don’t really want to be hiding from people. I do want to live somewhere where nobody can be going crazy. You got to be able to protect yourself. I want to be able to walk for five miles and smell trees and plants, and I don’t want to be walking with a ton of security guards around me. I don’t want to be with no big dude with no gun on him. I don’t want to do that.

BLVR: You were making “Anniversary,” “Dance Tonight,” and these really happy, up-tempo records, because that was the kind of energy you wanted to receive back from the crowd. Do you think that it’s a black artist’s responsibility to express optimism?

RS: I don’t know if I’d say it’s a responsibility, because you can be black and be like Radiohead, which I love. I just got out the car; I’m listening to Neil Young today. So I go from Neil Young to “Lil Ghetto Boy” to Kendrick to Shalamar, to [the] O’Jays, back to Radiohead, back to Little Dragon. I think your responsibility is to be you and to let everybody see and to leave something here that’s great. You’ve got to think about: do you really want to leave something here that’s great, or do you just want to play with these A&Rs and go through that regular car wash, that regular vacuum, and just be average? And nothing wrong with being just whatever you think you should be if you just trying to get paper. And most people just trying to get paper and some property and live they life.

II. Ray Wiggins, Bass Player for the Gospel Hummingbirds

BLVR: I know you come from a huge family, you got a lot of your start within the church, and you started playing the bass when you were six. I’m a firm believer, as a creative, that your gift finds you and then it’s up to you to really sharpen your talents. How did the bass find you?

RS: It found me through my dad, [who] used to have different guitars sitting around the house. We lived in separate places. Separate houses. So when I was up at his place, he always had an amp and a guitar there, and I used to always look at it. Then my brother started playing. Then the whole neighborhood played instruments. Then I heard “How Sweet It Is (To Be Loved by You)” by Marvin Gaye, and this amazing bass line, and I didn’t know what was going on. Then I saw somebody actually holding the bass and I sort of recognized the sound from a record. I started asking my brother to teach me things. Then people in the neighborhood started teaching me things, and after that point, my favorite toy was the bass. I had a race car set and stuff, and I’d play with them, but for the most part my bass was my G.I. Joe.

BLVR: Were you alone a lot with the bass or were you outside playing? Were you playing with your brothers?

RS: I was alone a lot at home, because we lived in two separate houses. My dad had a family before me, some family, then my mom had kids, so most of the kids were out of the house by the time I was maybe twelve. Everybody was pretty much out of the house. So I was the mistake kid. My dad: “Son, you were a mistake!” [Laughter]

BLVR: Fair. That’s probably most of us. I don’t know a lot of people that are planning kids.

RS: Yeah, but my dad just told me I was a mistake. I would have a lot of time in that house to just listen to records and play bass and just really home in on instruments and music and other bands. And I found myself listening to a lot of records and really walking around. I was sort of like that kid in that movie City of God, with the camera. Or I was like the kid Trey in Boyz n the Hood. All my friends were troubled kids.

BLVR: Were you trying to save them?

RS: No, I had to be bad just to be around them. But [there] was only so far I could go with having [parents] like my father and my mother. And my friends sort of respected it, so that’s when I would go back home and just end up playing bass for, like, five to six days, and playing in church, playing in school, being in talent shows, enjoying records, and just feeling that energy when I didn’t even know what the energy was at that point. At twelve I was still competing in school talent shows, playing in church, playing in gospel quartet groups where, like, Sam Cooke would’ve sung at the beginning of his career.

BLVR: Is that what the Gospel Hummingbirds were?

RS: Yes! That was my first group. My mom worked at a hospital in housekeeping. They all worked at the hospital together. My mom told them I played and they needed a bass player, so that was the first group I played with. I had my own business card and everything. It was funny.

BLVR: That’s amazing. What did the business card say?

RS: When you played for the group, they gave you a business card with your name on it. [Mine] said: “Ray Wiggins, Bass Player for the Gospel Hummingbirds,” and I carried those cards everywhere, and I would hand them out to people. So then after that, playing in high school. Castlemont High School [in Oakland] was a very prominent school program, almost like—it was like a Howard University. It was a school of the arts. So I went there and learned under these two teachers, Gregory Cole and Phil Reader. They both went to Grambling and Southern. They came to Oakland, and they set up for thirty years and taught inner-city kids. I was lucky enough to go through that program. Then I left and played with Sheila and Prince, and then came back and we started the Tonys. The Tonys was maybe the seventh or eighth band [I played with].

BLVR: To be in, like, seven or eight bands before Tony! Toni! Toné! hit, you had to have had such a relentless work ethic and faith. At that time do you feel like you were waiting to blow? Is that even part of what you thought was in your trajectory, or were you just playing music because you loved to play?

RS: No, I was just playing because I loved it. I never really thought about blowing up. It’s scary now to think about it. I didn’t go to college. I never took the SAT test. I never had a fallback plan or a plan to be famous, neither one. I just fell in love with the sound of music, and as I kept going, things started happening. But it wasn’t like I was blowing up. It was more [that] I had respect for music and people who already made it. So I just stayed a fan of people who made it, and I’m still a fan of famous people now. I don’t really feel too famous or anything like that. I just really like music.

BLVR: What do you think has kept you so humble?

RS: My dad was a person who didn’t like anything that had to do with glitz or glamour or fame, nothing. My father wore khakis his whole entire life, beige or blue. My dad was a boxer. I had a lot of fighters in my family, a lot of high temperaments. So I think music sort of allowed me to sit back and settle into my mind, and just watch other people be famous. I never wanted to sing. I really wanted to just play for people, so the singing thing was a surprise to me and everybody else.

BLVR: How did you find your voice?

RS: Stevie Wonder, I think. I just used to always hum his records. I never used to sing all the words to his songs, because I just made up my own words to his songs. Stevie was so melodic. Stevie and Motown and Michael Jackson really made me fall in love with melody. From watching TV shows like Taxi and Good Times and cartoons like The Bugs Bunny Show. All these shows had so many orchestras and symphonies. The O’Jays was my first concert I ever went to, at the Oakland Coliseum. They all had big-band orchestras and it was a lot of melodies. Once I figured out I had these big ears that could hear all kinds of things, I started putting it together for myself.

III. “Hollywood itself is the stick that the witch holds, with the star on it.”

BLVR: So many of our black artists feel like they’ve had to leave, or even have had the privilege to be able to leave the United States. We’re talking about as far back as James Baldwin. Paris was his salvation because he felt like American culture didn’t support his creativity. Where is your Paris? Is there a place you go to here in the States to support your creativity?

RS: My place is also Paris. My biggest following is in Paris, is in France. I’m into James Baldwin. I have art of James Baldwin’s; I read all his novels; I watched all his documentaries way before people got into [him]. I watched him talk to a whole street of kids in San Francisco—you might’ve seen the piece before; it’s on YouTube—and I’ve heard him talk. And a lot of musicians [like] Miles Davis, they all feel the same way. But I will say the States is very open now to Kamasi Washington and different people. It’s opening up. You don’t have to go to Paris to feel that anymore. It’s here. I travel abroad a lot; I could actually live in France and make a great living if I wanted to.

BLVR: What’s stopping you?

RS: My mom is eighty-three years old, and I want to be close to her, and she don’t want to leave. But I’ve stayed over there for long periods of time.

BLVR: Why do you think it’s Paris? What is it about the vibe in Paris, or the creative communities in Paris, that you feel really embraces you?

RS: It’s all the different African cultures there. The French colonized African countries, so I think all the Africans in France made the French white people understand rhythm. It’s not just the French people; it’s the African continent that’s right inside of Paris. And that’s where they heard all that rhythm at. I think they understand the real rhythm of the drum, and that’s why more Europeans love black music. They understand James Brown and Miles Davis. They understand what that art does to their minds, and as musicians we [can] feel how they receive it.

And I guess also I spend time in Copenhagen a lot. When you look at a building that’s still standing that was built in, like, 1200—for an artist, when you see architecture that’s so old and still standing, it sort of opens up those filters in your mind. You just walk around and you’re not looking at Google. What I’ve heard allegedly is that Hollywood itself is the stick that the witch holds, with the star on it.

BLVR: Wait. Tell me this again. The Hollywood sign?

RS: I don’t know if this is true, but it made sense: Hollywood is like when you see a witch on a broom and she has this stick with the star on it, her wand when she, like—blop—makes something appear: the stick with the star on it, that’s a “holly wood”; that’s what it’s called. So Hollywood can make gladiator sets and make you believe something is there. But when you travel abroad you actually see the real thing, and the rest of the world is the real thing. When you’re walking among real artists, real architects, real paintings, and huge cathedrals and you see all this art, it’s attractive to musicians, even if you don’t know what you’re looking at.

IV. “Black Girl–Black Boy Magic”

BLVR: Is it true that your first time performing in Brooklyn was at AfroPunk last year?

RS: Yeah, that’s true.

BLVR: That is nuts. How? How have you not been performing in Brooklyn?

RS: When I was playing with the Tonys and as a solo act, most of the venues were in the city. But New York is totally flipped now. I’ve only been in Brooklyn a handful of times. Every time I came to New York, I was sort of hanging out with my family out there, which is A Tribe Called Quest. So either I was in Queens or Linden Boulevard over there, Tip’s house, or I was in Jersey, Ali’s crib. And then they would be at Battery [Studios] in New York, [so] I was hanging out at Battery. I never went to Brooklyn that much unless I was visiting somebody [or] going over there to get something to eat. But now everything is in Brooklyn.

BLVR: Yeah, you can’t come to New York without coming to Brooklyn.

RS: I love Brooklyn. I was in Brooklyn last summer, at night. I was working with Solange. She did a little pop-up show, and I remember going out at night; it was still hot outside. I went to some pizza joint, and they had music and I was like, “Man, what’s that playing?” I knew the voice, but it was a new record; it was Anderson .Paak. And I just watched people sitting there, this very diverse group, a lot of cool music, and I’m like, Brooklyn feels so cool. Oakland is like that now, too, so home feels like Brooklyn.

BLVR: I’m glad you brought up Solange; I used to work as the music editor for her site. I know sonically what an impact you’ve had on her sound and her process. You guys started “Cranes in the Sky” quite some years ago. Was it the bass line that brought you back to the record?

RS: She had heard an idea, and I actually lost the track. And we created; we just fused. She liked the vibe of it. It was actually for my album, but it was a different melody. And she’s just super talented, man. She’s a super blessing. When I think about Solange, she’s another one of those people who came into my life as a friend who just kept coming back to me like, “Yo, I really like that song. Can you find…?” You know how Solange talks. [Laughter]

BLVR: Yeah, she naturally has that wave.

RS: She’s funny. She’s just really smart. So we had a record, she figured it out, came back to me, she sang it. Honestly, I’m just a vessel, man. I can’t speak for people like her and D’Angelo. Solange is another person where—I told [D’Angelo] the same thing—I’ve never really worked with you guys; we never worked. It was just always fun.

BLVR: Is that how you typically collaborate? Do you feel like most of your collaborations happen organically?

RS: Yeah, some of them. Not all of them.

BLVR: Who do you think has challenged you the most in a collaboration? And challenge doesn’t have to have a negative connotation, either.

RS: Right, right. I would say Solange, easily, because she has a different way of creating. When I was going through something, Solange was sort of my muse. Because I couldn’t really work when I was going through [stuff]. I was listening to “Alright,” and she had to hear everything I was going through: changing management and all kinds of crooked accountants and not-worthy people, and she was around to listen to it, and I would listen to her. But at the same time, we were making music. She would ask me to play something on bass and I was trying to go in, and sometimes I think that she would wanna say, That’s too much, and she would look at me like, Oh, I like that, let’s keep that. Or she was like, Oh, let’s drop out the drums, let’s do this here, like, Uh, I don’t want to use that. But that’s just our process, so it was a different challenge and it was very positive. We didn’t talk about money, we didn’t talk about contracts, we didn’t talk about who was producing, we didn’t talk about splits, we didn’t talk about executive producing, we didn’t talk about nothing. We just did it, and she just gave me whatever she gave me. I didn’t ask for executive producer; I didn’t ask for any of that. I just wanted to be a part of what she was doing. I didn’t find out what she gave me until people started talking about it.

BLVR: And would that be your ideal way to work with other people?

RS: No. [Laughter] Definitely not. She like family. It has to feel that way. I’m sure I could work with other people that way, but it was just a feeling. Her family is from New Orleans, my family is from Louisiana, so it was just a magical time. I’m not trying to be like all, you know, black girl–black boy magic, but sometimes it actually happens for real.

V. “I am a true soul guy.”

BLVR: During the time I was working with Solange, I think, between her True album and then “Cranes in the Sky,” there was such a heavy focus on reviving R&B music, because we had lost so much of R&B. What does it mean to you to work primarily within the genre of R&B and soul?

RS: I’m a soul classic guy. I couldn’t get away from it if I wanted to. Even though I listen to a lot of things, I grew up listening to blues: Albert King, B.B. King, Stevie Ray Vaughan, and Howlin’ Wolf. I grew up listening to hard-core blues, Memphis blues. So from that to gospel to Andraé Crouch, the Hawkins Family, to the Gospel Keynotes to Stevie [Wonder] to the Doobie Brothers, Parliament Funkadelic. I am a true soul guy, soul man, from Earth, Wind & Fire to Shalamar. I believe in R&B. I believe in rhythm and blues. I believe hip-hop is a part of R&B. Sometimes people used to say, “We ain’t on that R&B shit.” I’m like, “Yo, son, it’s all the same thing. You don’t have hip-hop without R&B. You don’t have hip-hop without jazz.” I just feel like, “Yo, you could make yourself look like you hard because you into hip-hop, but, son, you don’t really get hip-hop without James Brown. You don’t really get A Tribe Called Quest samples without jazz.” So it’s all one family. We just so creative as people that we can cut it up into so many different perspectives. I’m definitely just a soul brand who can cross many genres.

BLVR: With the culmination of your career, you’ve kind of been dubbed as this revival artist. Does that feel accurate to you?

RS: I don’t honestly know what I am. It’s hard for me to put my finger on what I actually do. ’Cause I don’t really look at it like that. I just look at [it] like I have an instrument. People say, “He’s so slept on,” you know; “He’s so this,” and I’m always like, “Whatever I am—”

BLVR: Do you feel slept on?

RS: No, not at all. But I know what they mean. They don’t mean anything offensive by it. They actually saying I should get more props than I get. But I don’t really care about props. Sometimes I kind of come down hard on awards. I don’t really care about Grammys and all that. I’m not knocking the Grammys association; I think it’s a great organization, but I don’t make records for Grammys or award shows. I make music because I’m that guy in the room who makes music, and my rewards are not going to be here on earth all the time.

When I make music, when it comes out of the speakers, those are my awards. I say my rewards are sometimes when I’m in my car and “Anniversary” comes on in the middle of the night and I just smile, like, Damn, I did that! I’m so stoked about this. That’s one of my songs. And then I get to hear “Lady” by D’Angelo or “Untitled,” or “Kissin’ You” by Total, or “Cranes in the Sky.”

BLVR: These are records that are imprinted into people’s lives. I remember watching my parents dance to “Anniversary.” They’re huge records, so I can only imagine what that means for you as an artist.

RS: And to me those are the rewards. I’m not slept on. I am very awake. I’m very feeling my energy, and I love it. And to even add to my career, to have someone like Solange [have] some success like that, and it’s something that I wrote and I was a part of, it just adds to the journey. People have to look at their career like a journey. You can’t knock anybody else’s music. You just have to hope that you connect with people. And my whole thing is connecting with people.