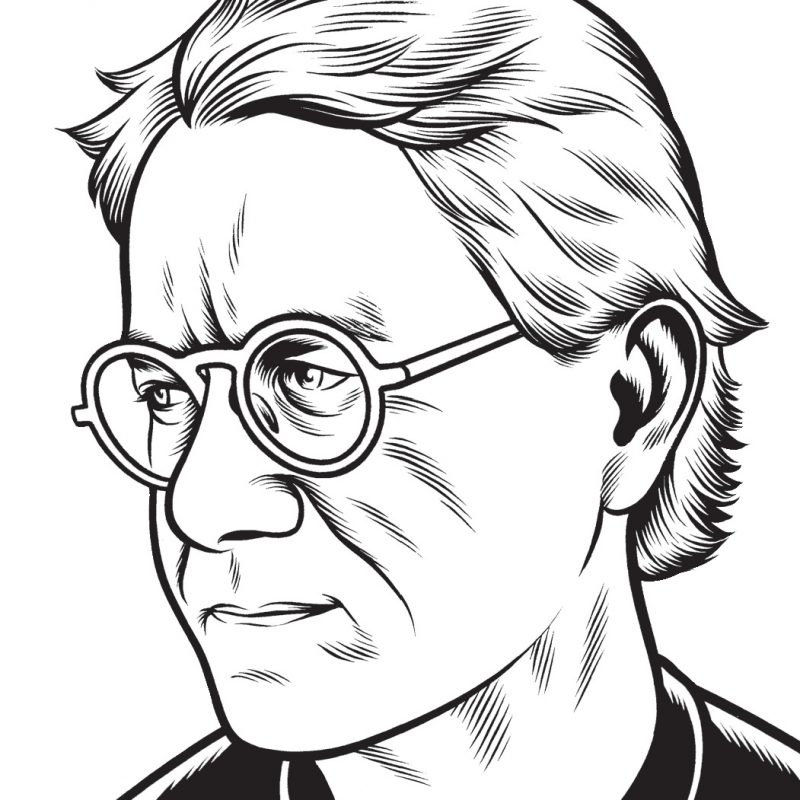

(1/2) Stephen Burt, Belmont: Poems (Graywolf Press) and Breaking Circus, “Driving the Dynamite Truck” (Homestead, 1986). “Yes, another / poem about flowers and kids,” Burt says early on in this collection, but the ruling themes are age and how to stave off cowardice—how to keep rage alive. “We have task force reports, // but no tasks, and no force” could be a sentimental definition of poetry as such, but that’s not how it works here. Rather, it’s a question: of course we have tasks, of course we have force, but what are they, and where is it? “You realize that you have become the person you are— / not who you were, not who you want to be, / but something to close to them, in exactly the way / the new low-intensity streetlights come close to the moon.” It may all come to a head in two poems that could not be more different: the searing, all-but-evaporating “There,” which can leave you stranded in abstraction and disconnection, and “In Memory of the Rock Band Breaking Circus.” “We barely remember you in Minnesota we love // our affable Replacements,” Burt, late of Macalester College, in St.Paul, writes of a mid-’80s Chicago and Minneapolis group—but Breaking Circus played “as if you knew you had to get across / your warnings against all our lives as fast / as practicable before roommate or friend / could get up from a couch to turn them off.” It’s that “them” that sticks: it’s the warnings that had to be turned off, not merely a record. And while it’s impossible to hear the band’s “(Knife in the) Marathon” today on its own terms, “Driving the Dynamite Truck” remains a weirdly balanced paean to destruction: a clipped, spoken vocal over a melody that comments on itself, a harsh, seemingly one-dimensional pulse that as it moves across the minutes picks up the back-and-forth dynamics of a Gang of Four record from five years before. There’s no warmth, no flattery of the players or whoever might be listening.

(3) David Lynch, The Big Dream (Sacred Bones). On Lynch’s first album, Crazy Clown Time, you were listening to an old man who never got over high school—who could never get his pornographic fantasies of Sue and Darlene and Diane out of his head. Here the voice is more that of an old codger unwilling to bring anything into too tight a focus, and the record rides on its music. “The most significant event of the twentieth century?” Kristine McKenna asked Lynch back in the twentieth century. “The birth of rock ’n’ roll,” he said, and now, in a different language than he spoke in Blue Velvet or Wild at Heart or Twin Peaks, he’s taking his place in that story. Like Nina Simone and the Stooges before him, he goes up against Bob Dylan’s deadly “Ballad of Hollis Brown” as if it were a test, and from the first two words you know you’re hearing about a real person, even if Dylan made him up.

(4) “The Genoa Tip,” The Newsroom (HBO, July 21). Jeff Daniels meets Emily Mortimer in a bar and she throws his drink into his lap. She’s trying to argue with him when Willie Nelson’s version of “Always on My Mind” comes on and Daniels turns his back, lost in the self-pity of the performance: “A hundred covers of this song,” he says like a penitent contemplating the philosopher’s stone, “and nobody sings it like him. Not even Elvis.” And something tells you that, deep inside the scene, he knows he’s lying, because Nelson gives himself and the listener a way out, and Elvis doesn’t, because he’s so gorgeously lying: he never thought of her once.

(5) Bob Dylan, “Suzie Baby,” Midway Stadium, St. Paul, Minnesota (July 10, minnpost.com). In a setting one attendee described as “totally Midwestern—when ‘All Along the Watchtower’ began, the train running past the stadium blew three perfect whistles”—Dylan went back to 1959. It was then that Buddy Holly’s plane went down, on February 3, just days after Dylan (then Bobby Zimmerman of Hibbing, Minnesota) had seen Holly play in Duluth; that, the next morning, Bobby Vee, then Bob Velline, the singer for a just-past-fantasy Fargo Central High School band called the Shadows, answered a promoter’s call for someone to fill in for Holly that night in Moorhead, Minnesota; that, in the summer, Zimmerman, calling himself Elston Gunn, briefly joined the Shadows on piano in North Dakota; that, in the fall, the renamed Bobby Vee and the Shadows went into the Soma Records studio in Minneapolis to record their first single, Vee’s own “Suzie Baby.” A subtle weave of doo-wop and rockabilly, it was a regional hit; picked up by Liberty Records, it made number seventy-seven on the national charts. Vee went on to become a teen idol, with six top-ten hits between 1960 and 1967, including the number one “Take Good Care of My Baby” and the gothic “The Night Has a Thousand Eyes”; by 1970 he was off the charts for good. Bob Dylan went on to become Bob Dylan; in his Chronicles, Volume One, he writes affectionately of taking the D train from Greenwich Village to the Brooklyn Paramount in 1961 to see Vee “appearing with the Shirelles, Danny and the Juniors, Jackie Wilson, Ben E. King, Maxine Brown,” and more. He went backstage: “I told him I was playing in the folk clubs, but it was impossible to give him any indication of what it was all about.” Last year, Velline, now seventy, having reclaimed his given name in 1972 with a singer-songwriter album called Nothin’ Like a Sunny Day, announced he had Alzheimer’s; this night in St. Paul he was in the audience to hear Dylan, seventy-two, dedicate his song to him. “I’ve played all over the world, with all kinds of people, everybody from Mick Jagger to Madonna. I’ve been on the stage with most of those people,” Dylan said musically. “But the most beautiful”—or did he say “meaningful”?—“person I’ve been on the stage with is a man who’s here tonight, who used to sing a song called ‘Suzie Baby.’ I want to say, Bobby Vee is actually here tonight.” With border-town guitar underlying every phrase, the tune came forth so delicately, suspended in time, as if Dylan, walking on eggshells and not cracking a single one, were glancing back to the past not from the present moment but from well into the future, where the song was, against all odds, with Velline dead, Dylan dead, still sung.

(6/7) Alfred Hayes, In Love (1953) and My Face for the World to See (1958) (New York Review Books). These two short novels, the first set in Manhattan, the second in Los Angeles, might remind a reader of a John O’Hara story, Nathanael West’s The Day of the Locust, Jean Rhys’s After Leaving Mr. Mackenzie, Ross Macdonald’s The Chill, but soon comparisons burn off, the settings float away, and you are in a swamp of sexual obsession where all places and all values melt down to worthless egotism: clenched fists or suicide. “There was nobody anywhere I could miss enough for it to matter and the terrible thing for me was that even when I missed them I knew it was not important and that nothing had been really lost for me,” says the man in In Love. “That was why she wanted it to be over. That was why she had gone back to him”—cue Elvis Presley, “Always on My Mind.” The books feel much longer than they are, because they are so dense, and their density comes from a relentless self-questioning, the first-person narrators locking themselves into their own torture chambers, making themselves talk, and never giving up everything, because then the torturer would turn away in disgust.

(8) Michèle Bernstein, The Night (Book Works). Clodagh Kinsella’s translation of a novel first published in Paris in 1961 as La nuit gives full purchase to the unflinching cold-ness inside this superficially cool parody of the nouveau roman hiding inside a parody of Les liaisons dangereuses inside a parody of the author’s life with her then husband, Guy Debord. In a new preface, Bernstein writes that, as a situationist and a member of “the lumpensecretariat,” she wrote strictly for money. “Lots of fashionable novels came my way,” she says. “I saw how I could write one that would immediately satisfy editors whilst deploying all the rules of the game. The protagonists would be young, beautiful and tanned. They’d have a car, holiday on the Riviera (everything we weren’t, everything we didn’t have). On top of that, they’d be nonchalant, insolent, free (every-thing we were). A piece of cake.” The cynicism shapes the characters, who revel in it, until it turns into nihilism, and then Bernstein lets them walk away, if they can. “For three weeks, Léda will sing in a cabaret near the Opéra: just long enough so that she isn’t forgotten, and can maintain her artistic reputation. Afterwards she’ll want to take a role in a film in Japan, and she’ll plan on taking Hélène, so they can eat raw fish together and assimilate a trimillennial culture. Hélène will write a letter to Bertrand, who will never reply. Waiting for Léda, she’ll head off alone on a health retreat in an isolated farmhouse in Provence. And then later she’ll die, on the way home, not far from Hauterives, where Postman Cheval’s Palais Idéal is an essential detour, at the wheel of a Porsche that will coil around a plane tree, as generally happens with this type of car in such encounters.” Bernstein and Alfred Hayes would have had fun killing a bar together.

(9) Lady Gaga, “The Star-Spangled Banner,” Gay Pride Rally (New York, July 28, youtube.com). Two days after the Supreme Court struck down the central section of the Defense of Marriage Act in United States v. Windsor, Lady Gaga appeared as an American version of Marianne, cool as an iceberg in a flaring black dress, holding a small rain-bow flag. “My LGBT fans and friends always said to me, I knew Lady Gaga when. Well,” she said, gesturing at the crowd, “look who the star is now! Now I get to say that I knew you when. Now I get to say I knew you when you suffered. When you felt unequal. When you felt there was nothing to look forward to. I knew you then—and I knew you when, but I really know you now.” Then she sang ten Super Bowls’ and four Inaugurations’ worth of the national anthem a cappella, with all of the blessings of the song in the full, clear tone of her voice and all of the war the song now celebrates in the ferocity in her face.

(10) Ruby Ray, From the Edge of the World: California Punk, 1977–81 (Superior Viaduct). Some of Ray’s photographs are typical musicians’ poses that anyone could have caught. But slowly the apocalyptic tinge in the title begins to pay off. Faces darken. Suspicion rises off of them like steam from the ground. There’s a sense of calm, and you can begin to feel as if you were watching a movie with the sound turned off, which in turn gives the impression that everything is happening in slow motion. A picture of Mick Jones of the Clash, leaping across a San Francisco stage in a posture of pure rock cliché, momentarily breaks the mood, because he’s acting like a star, his movement choreographed by people he’s never met, and in the best pictures here that’s not even a possibility: as in Greg Ingraham (The Avengers), you see people doing what they can to be insolent and free in a low-ceilinged room made of grime, heat, glare, and a queer sort of anonymous urgency most of all.