(1) Caroline Weeks, Songs for Edna (Manimal Vinyl). An “English Rose” (so described in a press release) setting Edna St. Vincent Millay to music? On the sleeve a leafy, garlanded Ms. Weeks holds a conch shell to her ear—the better to hear the glowing girl-poet of “Renascence” in 1912, a dead alcoholic in 1950? There’s a swan, for the 1921 “Wild Swans,” pressed onto the disc. I put it on, betting the music would be worse than the packaging.

That was a while ago, and I haven’t taken it off. Weeks sings Millay’s words slowly. She sings Millay’s rhythms, or dowses for them. “Her poetry, you soon found out, was her real overmastering passion,” her old Greenwich Village friend Edmund Wilson wrote in 1952. “She gave it to all the world, but she also gave it to you.” A reader entranced by Millay’s lyricism—not yet catching the way a blunt nihilism would reach up out of the ether of a poem and scratch its face—can always convince herself she’s the “you,” and read Millay as if she were Sylvia Plath or J.D. Salinger, which is to say as if Millay is her. But Weeks sings—high, fingering her guitar, maybe with clarinetist Peter Moyse singing wordlessly behind her—as if she’s heard something others haven’t heard.

Death—anticipated, remembered—is all over the songs. The album breaks after its first five pieces (among them “Renascence,” “What lips my lips have kissed,” “Wild swans”), beginning again with “The return,” from 1934, and you can almost sense an anchor being dropped.

Weeks will nearly stop, letting a piece breathe. When she moves back into it you can hear that she’s hearing something she herself hadn’t heard before. This rhythm of encounter makes it all but impossible to follow the tracks as tributes, or homages, even if you’re reading along as Weeks puts her mouth around Millay’s words, or her body.

“It was difficult for the romantics of the twenties to slow down and slough off their youth, when everything had seemed to be possible and they had been able to treat their genius as an unlimited checking account,” Wilson wrote. “One could always still resort to liquor to keep up the old excitement, it was a kind of way of getting back there.” As Weeks heads to the end of her project, the pace seems to slow even more, but more seems to be at stake. Each step carries the voice closer to a last word, whatever it might be—you’ll know it when you find it. The sulfurous air of David Bowie’s profoundly creepy “The Bewlay Brothers,” from his 1971 Hunky Dory, seeps into Weeks’s songs as if under their doors. There’s a sense of violation, of salvation as a joke, and a pagan self-destruction—getting lost, in a forest where priests can’t go—the only destination worth seeking.

There’s no resolution in any single one of Weeks’s pieces. There’s no progression. Each song leaves the singer where she found it, or it found her. Maybe that’s why I keep going back to it.

(2) Bob Dylan, “Theme Time Radio Hour: Madness” (Sirius XM, February 5). “Here’s a man, that some call the William Faulkner of jazz. Now, I’ve got to tell you. I’ve heard this guy play since the sixties, and I’ve never heard anybody call him ‘the William Faulkner of jazz’—but there it is in a book. I mean, somebody just wrote that. I can’t imagine anybody calling him ‘the William Faulkner of jazz.’ I mean, that’d be like calling Garnet Mimms the Gabriel García Bernal of soul music,” Dylan said, apparently introducing Gael Garcia Bernal to Gabriel García Márquez. “It’s just not done.

“I’m getting excited over nothing. Let me just play the record. By the way—I consider William Faulkner to be the Mose Allison of literature. Here they are, together again, Mose Allison and William Faulkner, singing the Percy Mayfield song ‘Lost Mind….’”

(3) The Drones, Havilah (ATP/R). Gareth Liddiard could come from the far side of a Clint Eastwood western—set in his own Australia. There’s a desperation in his whole demeanor that speaks for some titanic struggle—resignation versus justice, or justice versus peace of mind. The tired way Liddiard sings “to be nailed to a door” (“Luck in Odd Numbers”) could be translated by any of those words. There are echoes of Neil Young or Rick Rizzo of Eleventh Dream Day in his guitar playing—a manic ditch-digging. There’s nothing here to match the death march of “Jezebel” on the 2006 Gala Mill—but what if there were?

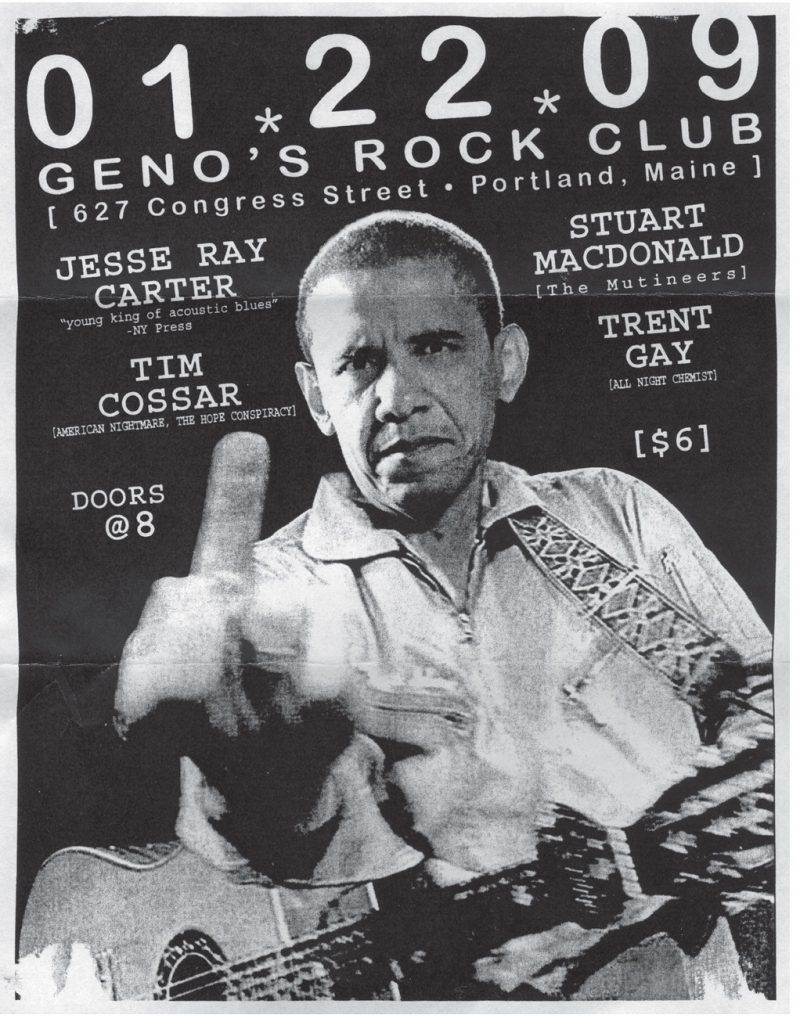

(4) Flyer, Portland, Maine (January 28). The Obama that those of little faith dream of and that Obama refuses to be—the avenger, not the advertised Jesse Ray Carter, an OK Chris Smither–like bottleneck player—but where did whoever put Obama’s head onto the famous Jim Marshall photo of Johnny Cash find that scowl?

(5/6) James Tate, “The Wine Talks” and Charles Harper Webb, “The Secret History of Rock & Roll,” in Third Rail: The Poetry of Rock and Roll, edited by Jonathan Wells (MTV Books, 2007). Tate is aiming for a sting, and even though he moves from a pleasant moment to a cruel joke, you’re still blindsided when it comes. As a technical performance the poem carries its own thrill. Webb begins with what you can take as a joke—

Elvis Presley, Bo Diddley, Bill Haley & the Comets

were lies created on recording tape by the same Group

who made The Bomb, with the same motive:

rule the world

—but after three pages he’s made his case.

(7) Allen Toussaint, The Bright Mississippi (Nonesuch). Mostly solo piano, looking for the right elegy. But the opening “Egyptian Fantasy” lets you think there might be a pyramid under New Orleans where they have parties only on February 29, accounts of which are kept in a special copy of Ishmael Reed’s Mumbo Jumbo.

(8) Sometymes Why, “Glorious Machine” on Your Heart Is a Glorious Machine (Signature Sounds). Ruth Ungar Merenda of the Mammals, Kristin Andreassen of Uncle Earl, Aoife O’Donovan of Crooked Still—and it’s O’Donovan who has the gift of atmosphere, who can change the temperature of a room. You can hear that on Crooked Still’s erotic embrace of old folk songs on its 2006 Shaken by a Low Sound, and how it all somehow vanished last year on Still Crooked—as if the cute title wasn’t a giveaway. You wouldn’t necessarily expect better from a group that spells sometimes with a y. But one soft deep breath into the title song and all resistance crumbles. “If you give me one reason not to leave, I’ll show you all the tricks up my sleeve”—as O’Donovan sings the words they find a circular pattern. They draw a circle around the people in the song. Anybody else, you can think, would repeat lines that good. O’Donovan lets them hang over the song, leaving you aching to hear them again.

(9) William Hogeland, “American Dreamers” in Inventing American History (MIT Press). On the lies surrounding two figures no one else would think of as political doppelgängers: Pete Seeger as a Stalinist, and William F. Buckley Jr. as a racist. Hogeland writes quietly, carefully, never letting his knowledge of the entire frame of reference of his argument make the reader feel ignorant, but he can hit. Pete Seeger’s having “inherited communism from his father,” the musicologist Charles Seeger, was a “decisive event in the history of American vernacular music.” Buckley’s 1957 National Review editorial calling for the suppression of black voting on the grounds that, as Buckley put it, “the claims of civilization supersede those of universal suffrage,” was, Hogeland shows, never disavowed, only smoothed away; it was of a piece with Buckley’s whole career as “the leisure-class warrior-philosopher, provoked to militancy by ubiquitous barbarism… battling to push back both the mob and the weak-willed mob enablers who were ruining the civilization that had produced his own gorgeousness.” Reaching the end of this forty-page essay, you can imagine such scores are there only to prepare the ground for a passage that is more damning for its apparent affection: “Seeger and Buckley were public romantics. When they were young, and without regard for consequence, they brought charisma, energy, and creativity to dreaming up worlds they wanted—possibly needed—to live in. Because they made those worlds so real and beautiful that other people wanted to live in them too, they became larger-than-life characters, instantly recognizable a long way off, not quite real close up, and never quite grown up even when old.”

(10) The Land Beyond the Sunset (Google Films/YouTube). A fourteen-minute film from 1912, directed by Harold Shaw, about the New York Herald Tribune’s Fresh Air Fund—and the furthest thing from a documentary imaginable. There are the shadows of spirits on a shed, a magic book, and a child stealing a boat so that he can float off the end of the earth, just like Enid boarding her bus at the end of Ghost World.

NOTE: In my last column, I said that the Adverts’ perfect 1978 album, Crossing the Red Sea with the Adverts, featured a sleeve that “showed the title on a billboard with the ugliest public housing in the city behind it.” The Adverts were much sharper than my memory. The billboard read land of milk and honey.

Thanks to John Coleman, Tom Denenberg, and Tom Luddy.