(1) Fiery Furnaces, I’m Going Away (Thrill Jockey). Musicality in speech is a common theme; the peculiar delight in the Fiery Furnaces’ eighth album in their six years is the realism of speech in their songs. The music is a given, so if you catch, say, the way Eleanor Friedberger turns her words, “Well, I thought I was thinking, but apparently not,” whatever context the words might inhabit in their narrative drops away, and you might be transported to a city street and enveloped by the feeling not of listening to a performance but of hearing a woman on her cell phone as she strides past you, with precisely the intensity and surprise of a smell taking you back to a face or a voice you haven’t thought of for years.

(2) Robert Cantwell, “A Harvest of Illth,” in If Beale Street Could Talk: Music, Community, Culture (University of Illinois Press). Cantwell is a subtle writer, and his collection of essays on the transformation of everyday life by art that resists disappearing back into the ordinary and the predictable is full of paradox (“The disc renders the performance silent, as the photo renders its subject invisible, each not merely representing, but replacing the other”). But in “A Harvest of Illith”—John Ruskin’s word for a form of wealth that “as it leads away from life, it is unvaluable or malignant,” here naming Mississippi blues 78s made in the ’20s and ’30s as accumulated by a few young men in the ’40s and ’50s—Cantwell finds his way into a kind of frenzy. If Beale Street could talk it might say this: “Like a bus driver caught in a skid”—imagine a tourist bus, with the driver on his intercom, “That’s where they had the Palace Amateur Nights, they say Elvis sang there before anyone knew his name, Oh shit, hold on!”—“the Delta blues thrusts the musician into a swiftly proliferating emergency that tests not only his competence as a musician but his grasp of the whole nature of his body and his instrument in the midst of the wider context of natural laws of which he and it are parts.”

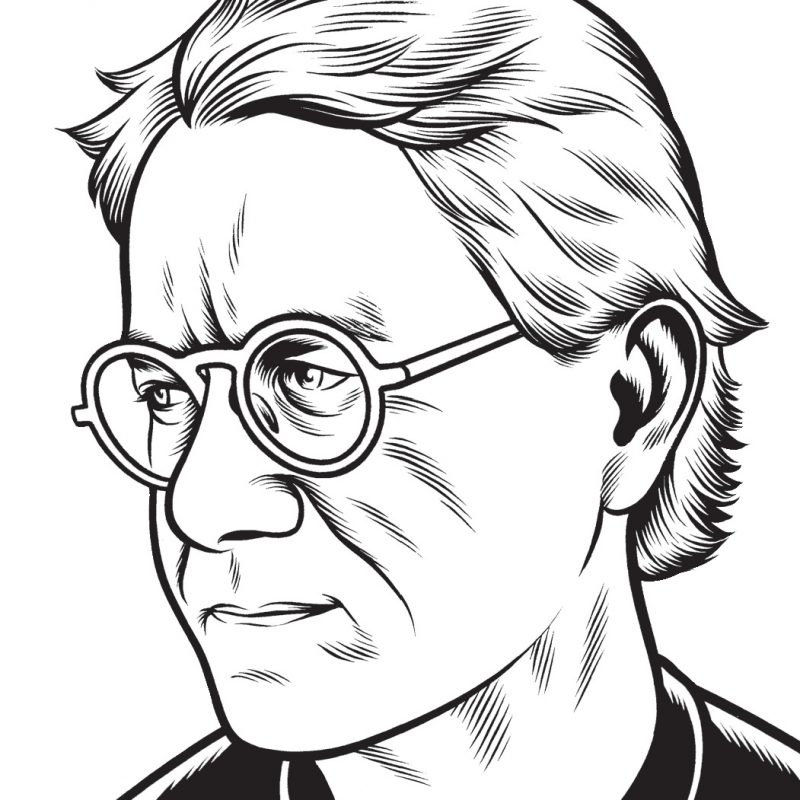

3 & 4) David Thomson, “After Citizen Kane—a New Socratic dialogue” (McSweeney’s 31) and Adam Lambert, “A Change Is Gonna Come” (American Idol final, Fox, May 19). Thomson has Susan Sontag trying to get Franz Kafka, Virginia Woolf, Charlie Chaplin, and Ernest Hemingway to vote against Citizen Kane in the 2012 Sight & Sound poll on the greatest movies ever made. “I always vote on American Idol,” says Woolf. Would she have voted for Adam Lambert, who...

You have reached your article limit

Sign up for a digital subscription and continue reading all new issues, plus our entire archives, for just $1.50/month.

Already a subscriber? Sign in