You don’t have to listen very closely to realize we’ve been wrong for all these years. It’s not a difficult phrase to remember, and she repeats it again and again and again, clutching her knee as she rocks back and forth like a child hurt on a playground. It is, in fact, not a phrase at all, but a word—just one—and though we hear it mostly as a keening, inarticulate wail, it’s also impossible to mishear. The word is why.

In the video—which will be shown on the news again and again in the weeks that follow the incident—she says the word three times, stopping only when she is spirited away from the cameras in her father’s arms, her face pressed fearfully against his. She looks, in her lacy white costume, like nothing so much as an anxious young bride being carried over a threshold she isn’t quite sure she’s ready to cross.

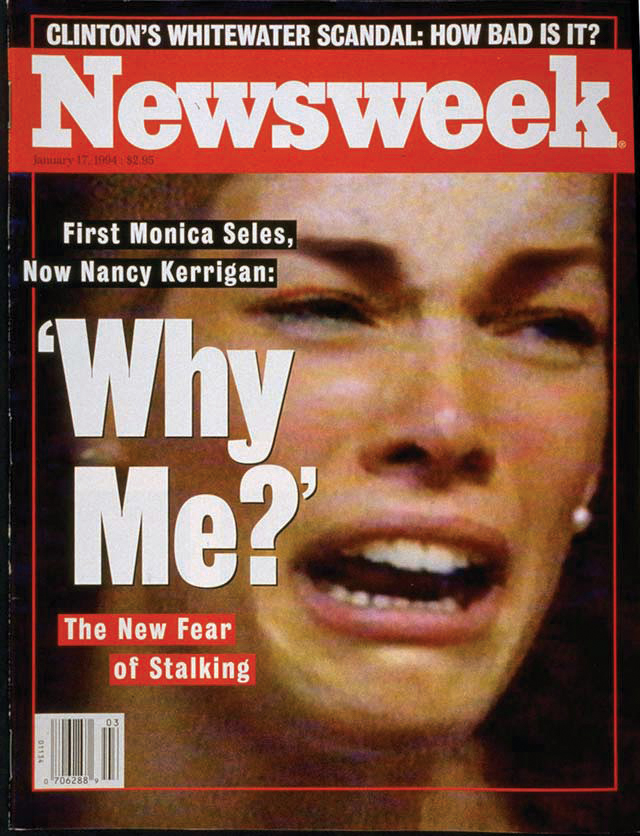

For all the hours she has spent in the public eye prior to this moment, and for the many more hours she will spend there yet, she has been stoic, strong, reserved. She was famous before, for her skills as an athlete and as a performer, but this moment of anguish will make her an icon. Newspaper headlines and magazine covers and reporters and talk-show hosts and families joking in the car and around the breakfast table and on the couch as they watch her on TV will quote her, now and for years to come—or at least they will think they are quoting her. But they will say, without fail, the one thing she didn’t say: “Why me?”

Twenty years later, we are still trying to answer this question. And if we have been mishearing something so simple for so long, we have to wonder what else we have been mistaken about.

*

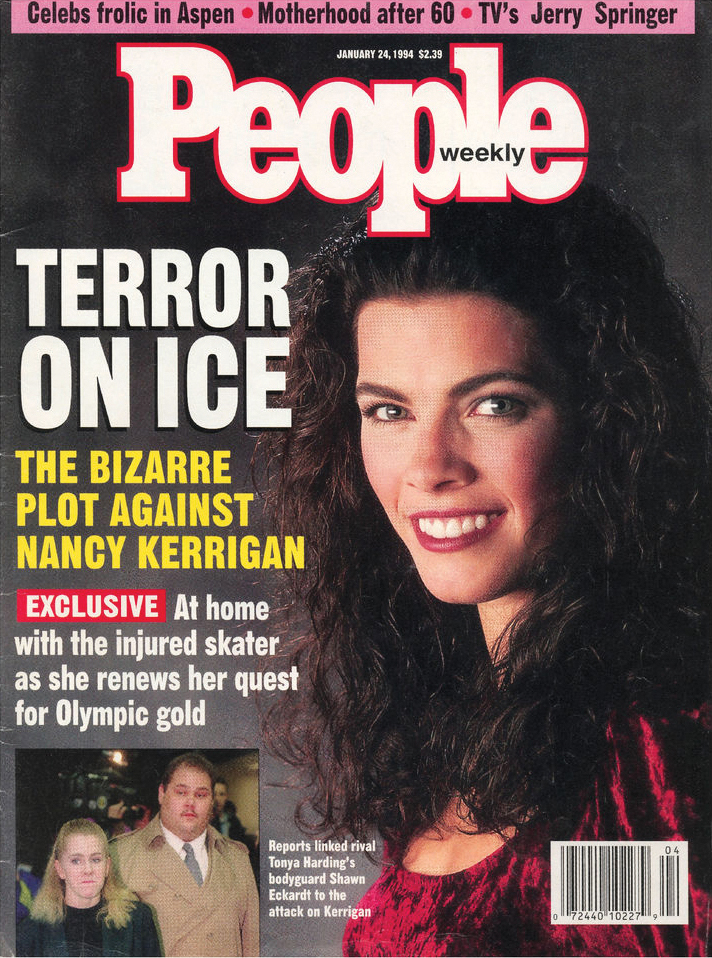

First, the facts: on January 6, 1994, Nancy Kerrigan left the ice after a public practice session in Detroit’s Cobo Arena, where she was to compete in the US Figure Skating Championships the following day. “I was walking toward the locker rooms, away from the ice,” she said later, “and someone was running behind me. I started to turn, and all I could see was this guy swinging something… I don’t know what it was.” The man had been aiming for her left knee, but missed, instead hitting her on the lower thigh. Later, in an exclusive interview with Jane Pauley, Nancy put a brave face on the assault, reassuring Americans that she knew how lucky she was, because if the man had actually hit her knee she would undoubtedly have been unable to skate at the Olympics. She had to feel thankful, she said in a moment of good-natured wit, for his poor aim. By then, however, it didn’t really matter what she had to say. To the public, her injury had already been transformed into a gangland kneecapping, while the assailant’s weapon, revealed soon after the assault to have been a collapsible police baton, was routinely characterized as everything but—a crowbar, a wrench, a lead pipe—in an ongoing public game of Clue. Nancy, meanwhile, would be remembered not for anything she was doing now, but for the way she had acted immediately following the assault. There was room for only one image of Nancy in the public’s memory, and it had already been chosen.

By the time the cameras caught up with Nancy, her attacker had fled into the parking lot, and was visible on the film played on the news that night—and endlessly replayed, reproduced, referenced, and eventually parodied over the next six weeks—as a blurry black splotch about to disappear through the arena’s Plexiglas doors. The assailant lost, the camera then turned to his victim, who had collapsed on the ground, sobbing, as medical personnel tended to her injured leg. The camera zoomed in on her as closely as possible as she wailed, “Why? Why? Why?” When asked what she had been hit with, she responded: “I don’t know, some hard, hard black stick. Something really, really hard. Help me. I can’t move. I’m so scared. I’m so scared. It hurts so bad.”

The next day, Nancy, unable to skate, watched as Tonya Harding became the national champion for the second time. Tonya had won the title for the first time in 1991, and in the process had also become the first American woman to land a triple axel in competition. She never regained the success she had enjoyed that year, and her career had been on the decline since her disappointing performance at the 1992 Olympics, when she began losing the ability to land her famous triple axel in competition. Since then, she had come in sixth at the 1992 World Championships, and fourth at the 1993 US Championships, not even managing to make the American team at Worlds. Her only successes, including a bronze medal at Skate America a few months before, seemed to take place when Nancy wasn’t around, and this time was no different: with Nancy out of contention, Tonya delivered a stronger performance than she had in recent memory. “I know there are a lot of people out there who think I’m a has-been,” she had told the press. “I have something to prove tonight.”

Tonya still didn’t have her triple axel, but she landed a spectacular triple lutz. Her spiral sequence—the move Nancy was famous for—displayed more flexibility and grace than it ever had before. After turning up at too many competitions looking exhausted and out of shape, Tonya was dynamic and disciplined again, showing her strength in the deep edges that had wowed judges since she made her senior debut in the mid-᾽80s. Yet Tonya’s skating showed not just a return to form but a maturation. It seemed as if she had finally stopped fighting against her sport, and, remembering her old love for it, was again greeting it as a friend. “For all the skeptics who felt Tonya’s peak had passed,” commentator Peggy Fleming said, “I think she has proved she still is a winner even without that triple axel.”

She was also, notably, a winner without Nancy Kerrigan, though anyone who watched Tonya skate that night would have a hard time believing that she couldn’t perform just as well as Nancy. At the time, figure skaters were scored by nine judges, who each awarded two scores, one for technical merit and one for artistic impression, with 6.0 representing a perfect mark. Tonya had been awarded 6.0s in the past, and at her career peak, when she was able to land axel after axel, both her technical and her artistic scores had been dominated by 5.9s and 5.8s. Tonight she earned those scores again. At the end of the evening, Tonya’s marks were even higher than the ones that had allowed Nancy to win the national title the year before.

Was Tonya able to pull out a better skate simply because she wasn’t sharing the ice with Nancy that night? Perhaps. In the few years they had occupied the spotlight together, Nancy had gradually come to embody all the qualities that Tonya, it seemed, would never quite be able to grasp. Nancy’s presence was elegant and patrician despite her working-class background; her skating was as graceful and dancerly as Tonya’s was explosive and athletic. Audiences and commentators wanted elegance and grace; they wanted Nancy, and as good as Tonya was—as great as Tonya was—it had become painfully clear, over the last few years, that she would never quite be right. With Nancy out of sight, perhaps Tonya could for once remember all she was, rather than all she wasn’t, and deliver the skate of a lifetime.

And perhaps, too, the judges had something to do with it. Audience members weren’t the only ones who liked Nancy: the judges liked her, too, and had ways of showing it. When it came to the technical merit score, with its necessary deductions for errors and falls, judges’ rankings were more or less objective; artistic impressions left a little more room for interpretation. Despite its specific list of requirements—for musicality, use of the rink, deportment, and other qualities—“artistic impression” was a far more elastic score. Judges could allow their scores to be influenced by a skater’s costume, or by a skater’s appearance, or simply by some ineffable quality that struck them, somehow, as “right”—right for the moment, right for the event, right for the sport. Many judges saw these qualities in Nancy. “She’s a lovely lady,” an Olympic judge, who preferred to remain anonymous, told sports writer Christine Brennan. “She was raised as a lady. We all notice that.”

At the time, judges’ opinions were also far less reliable—and far more malleable—than many outside the sport would have imagined. Working without the aid of instant replay or slow-motion analysis, judges—some of whom were former skaters, many of whom had simply devoted their careers to the sport—had to judge a program as it happened, with no opportunity to take a second look at a skater’s performance. Judges were all too likely to miss skaters’ errors on the ice—and at times did—making even the most objective portion of the score surprisingly unreliable. It was standard practice for judges to “leave room” in their scores, meaning that if a skater performed phenomenally at the beginning of the evening, they would be likely to receive a lower score than if they had performed at the end of the night, so that later and potentially better skaters might have a chance to win. Judges sat in on practice sessions, and scored skaters not just on their performance on the night of the competition but on the skill they displayed over a period of time. And judges were also likely to prop up the scores of skaters they knew to be solid competitors, even if the performance they were actually scoring was mediocre.

If Nancy Kerrigan had skated in the US Championships that night, and had skated just as well as or even somewhat worse than Tonya Harding, she likely would have beaten her, not because of the quality of her performance but because she was more consistent, more admired, more in keeping with the sport’s ideals, and, above all, because she was the American skater who seemed the likeliest to bring home Olympic gold. The judges knew it. Nancy knew it. Tonya knew it. The only thing that remained a mystery was just who had taken Nancy Kerrigan out of contention, and why.

But that night, none of those questions mattered, and none of the unspoken rules of judging held true. Tonya won the gold by a generous margin. She would be going to the Olympics, but so would Nancy, who, even injured, was still more valuable to her country than any other skater in good health, and was given a bye despite her inability to compete at the US Championships. Unlike Tonya, Nancy didn’t need to prove her worth.

*

Nancy Kerrigan may not have had the protection she needed to ward off an assault at the US Championships, but Tonya Harding did: namely, a man named Shawn Eckhardt, who at the tender age of twenty-six boasted an Errol Flynn mustache, a three-hundred-pound girth, an ambitiously fabricated résumé studded with counterterrorism and espionage, and a company called World Bodyguard Services, whose headquarters occupied a spare room in his parents’ home. Though he described himself as Tonya’s bodyguard, he entered her life as a high-school friend of Tonya’s ex-husband, Jeff Gillooly. According to Shawn, it had been upon Tonya’s return from the NHK Trophy the previous December that Jeff, believing the judges had shafted her, suggested they might find a way to keep Nancy out of contention for the Games.

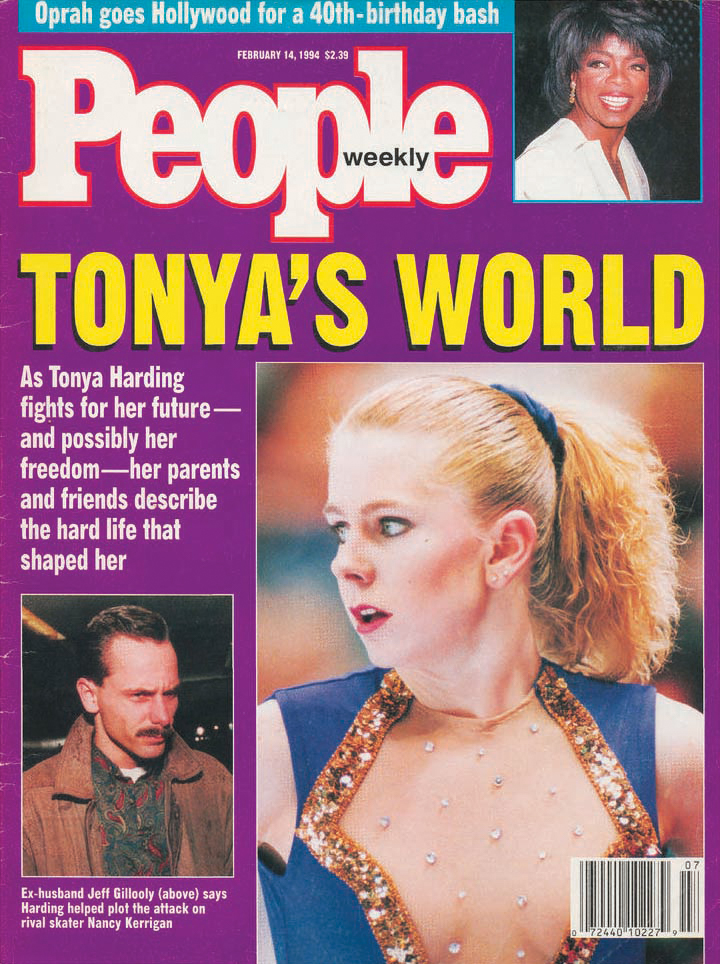

Later, Tonya would claim that the plot had been motivated completely by Jeff’s greed, that she had been aware of it only after the fact, and that she had failed to come forward only because she feared Jeff would kill her if she tried. Jeff would claim it was Tonya’s idea from the beginning, and that he had merely gone along with her wishes so he could help make her dreams come true. The public, given the opportunity to select one story as the more plausible—and juicier—version, overwhelmingly chose the latter. It seemed there was nothing more enjoyable, in prime time or real life, than a devious plot with a manipulative woman at the top.

In his search for someone to carry out the assault, Shawn called his friend Derrick Smith, a Phoenix man who aspired to open a paramilitary survival school in the Arizona desert, and who in turn suggested his twenty-two-year-old nephew, a weightlifter, steroid enthusiast, and aspiring martial artist named Shane Stant. Shortly after Christmas the two arrived at World Bodyguard Services headquarters for a meeting with Jeff and Shawn. The tape that Shawn secretly made of the meeting that night recorded both his suggestion that they hire a sniper to murder Nancy, and Jeff responding, “What can we do less than that?” Figure-skating insider that Jeff was, it was his idea to break her landing leg. Shane would do the job for the bargain price of $6,500, and Derrick would drive the getaway car.

What happened next was soon known to the world, even if the identity of the assailant was not. But Smith’s anonymity wouldn’t last long. The Detroit police—and, to an increasing degree, the public—immediately began suspecting that Tonya and Jeff were involved, but they didn’t have much to go on until an anonymous woman called the Detroit police and voiced her suspicions that Tonya, Jeff, Shawn, and some other men in their employ were behind the attack. She also sent unsigned letters to the FBI, and to KOIN-TV and the Multnomah County DA’s office (both in Portland, Oregon, where Tonya lived) detailing the same suspicions. Later, she would be identified as Patty May Cook, an acquaintance of Shawn Eckhardt’s father, Ron, who called Patty up every few weeks to tell her about his problems and occasionally tried to initiate phone sex. She had barely listened to him as he bragged about his son’s espionage career one night, but she was horrified when, the following day, she turned on the TV and realized Shawn’s plans had come to fruition.

After the attack, though, the gang began to fall apart. Shawn, his initial excitement perhaps turning to guilt, played his tape of the planning meeting for Eugene Saunders, a classmate in his community college paralegal class. Saunders, a twenty-four-year-old pastor, came forward with what he had heard, speaking to both the FBI and the Oregonian. As the story gained notice, reporters started hounding Tonya and Jeff, and Tonya’s practice sessions became jammed with nearly as many TV cameras as the Olympics would be in a few weeks’ time. The FBI also began monitoring their house, and the evidence began mounting against them, though not quite as quickly as the public’s opinion.

Finally, on January 18, 1994, Tonya came forward to the FBI, saying she was frightened of Jeff, and telling them everything she felt she could. Jeff was arrested. The US Olympic Committee notified Tonya that it was reviewing her status, and Tonya secured the services of her coach’s husband, a prominent Portland lawyer, who filed a lawsuit for twenty million dollars in damages in the event that Tonya was kept from going to the Games. On February 13, the USOC announced its controversial decision to keep Tonya on the Olympic team. On the morning after Valentine’s Day, Tonya left for Lillehammer. Before she even landed in Norway, she began the endless round of press appearances that would take up much of her time at the Games, granting an in-flight interview to Connie Chung somewhere over the Atlantic. “I feel really lucky,” she said. For perhaps the first time in her life, Tonya Harding was flying first class.

*

In 1991, when Tonya Harding became the second woman in the world to land a triple axel in competition and became the US champion in the process, Nancy Kerrigan was standing beneath her on the podium, her crooked teeth hidden beneath a shy smile, and a bronze medal hanging around her neck. A few weeks later, Nancy would win bronze again at the World Championships as Tonya Harding and Kristi Yamaguchi, who had medaled silver at the US Championships, again stood above her. This time, their roles were switched: Kristi won the gold, and Tonya, even after landing a more impressive axel than she had at the US Championships, took home the silver. Despite whatever disappointment Tonya may have felt, it was a landmark moment for American ladies’ figure skating, marking the first time a single nation had so dominated the podium at the World Championships. It also gave each of the podium’s proud young occupants her first true taste of fame—and prepared them, however inadequately, for the pressure and scrutiny they would experience at the Olympics the following year. For Tonya, the 1992 Olympics would seem to mark the beginning of a baffling career decline. For Nancy, they would mark the beginning of an equally swift—and perhaps equally terrifying—rise to fame and fortune.

At that year’s Games, Nancy’s skating was flawed, but her image wasn’t. Though her imperfect performance was good enough to keep her in the medals on a night when not even Kristi Yamaguchi managed a clean skate, the solid and ambitious jumps Nancy did land attracted considerably less attention than her costume: an unadorned white leotard whose elegant lines matched her own, and whose sweetheart neckline seemed to echo all too aptly the role she had begun to play in American life. By this time, the promise Nancy had displayed in 1991 had attracted the attention of some key individuals, including Vera Wang, a former figure skater who designed Nancy’s costumes pro bono. Nancy got her teeth fixed, and began to get acquainted with the feel of the cameras following her every move, though she never grew to like it. Her performance at the 1992 Games was not a triumph of athleticism—though even then Nancy was a far more formidable athlete than anyone gave her credit for—but it was a triumph of image-making. To the commentators, she was “lovely,” “ladylike,” “elegant,” and “sophisticated,” and the audience agreed. Vera Wang had based the design for Nancy’s costume on a dress from her bridal boutique, and as Nancy took the ice in Albertville, France, skating to the theme from Born on the Fourth of July, she seemed to be presenting herself as America’s hopeful young bride. Even her lack of competitive savvy gave her an air of innocence and sincerity: she was radiant when she landed a difficult jump, and appeared near tears after making a mistake. She had the style and grace of a woman, but the bashfulness and sincerity of a girl. She was beautiful without being sexual, strong without being intimidating, and vulnerable without being weak, and in the end she embodied no quality quite so perfectly as she did the set of draconian contradictions that dictated a female athlete’s success. Once again, Nancy went home with the bronze. Tonya, who had finished narrowly behind her, in fourth place, went home with nothing.

As the 1994 Games drew closer, and as Tonya’s skating grew weaker and Nancy’s stronger, singling her out as America’s only serious contender in ladies’ figure skating following Kristi Yamaguchi’s retirement, Nancy signed endorsement deals with Campbell’s Soup, Reebok, Northwest Airlines, Seiko, and Ray-Ban. It was as if the rewards for Olympic championship had already been bestowed on her: she was sure to win, and even if she hadn’t yet, she looked like a winner. Somehow, she had broken the rules that for so long had dictated the shape of a skater’s career: years if not decades of penury and toil, and a reward if and only if you won the gold. Those rules had applied to everyone else, but they didn’t apply to Nancy. She didn’t need the gold medal around her neck so long as she had a neck lovely enough to deserve it.

It was a new variation on an old theme, and one perhaps best exemplified by Peggy Fleming, whose Olympic victory had set the standard for the career—and the fame, and the wealth—a female figure skater might aspire to. Not quite twenty-five years before, at the 1968 Grenoble Olympics, Peggy, coltish and wide-eyed as a young Audrey Hepburn, had become the only American athlete to win a gold medal at the games. Upon her return home, she had been crowned America’s sweetheart.

Her subsequent fame was unprecedented, even if her victory was not. Tenley Albright, who in 1956 became the first American ladies’ skater to win an Olympic gold medal, left the sport altogether after her win, attended Harvard Medical School, and became a surgeon. Following her victory at the 1960 Games, Carol Heiss had skated in a few ice shows and appeared in a Three Stooges movie, then retired from skating altogether in 1962, quietly returning to the sport in the 1970s to work behind the scenes as a coach. But Peggy would never have to attempt such strenuous work, or aspire to such anonymity. Her job now was to make a living being—and selling—herself. Over the years, she appeared in ads for L’eggs and Hanes pantyhose, Concord Mariner and Rolex watches, Halo shampoo, Colorado Interstate Gas, Trident gum, Bell Telephone, the United States Postal Service, Kellogg’s cereal, and Equitable Life (“Maybe your girl won’t become a sports star like Peggy Fleming. But every youngster—including yours—can be as physically fit as the most talented athlete”). She met Lyndon Johnson on a trip to the White House, visited Vietnam veterans in the hospital, was named the Associated Press Athlete of the Year, and rode through her homecoming parade perched on the back of a convertible, clad in a smart double-breasted skirt suit, cradling a drift of red roses, and looking as dewily innocent as Jackie Kennedy had, sitting in the Dallas sunshine, before the first shot cracked through the air.

In 1973, after Janet Lynn had tried for both the gold medal and the position of America’s sweetheart at the 1972 Sapporo Olympics and finished with a disappointing bronze, Peggy, title still intact, appeared in an hour-long special titled—rather unimaginatively but nonetheless intriguingly—Peggy Fleming Visits the Soviet Union. (Only Nixon could go to China, but only Peggy Fleming could go to the USSR.) Peggy’s career had spanned some of the most frightening years in the United States’ recent memory: the issue of Life magazine on whose cover she appeared, rosy-cheeked and radiant after her gold-medal win, advertised itself with two headlines, schizophrenically promising stories of both OLYMPIC CHARMER PEGGY FLEMING and KHE SANH. Some Americans might have needed the magazine to remind them just who this Olympic charmer was, but the Vietnam combat base required no introduction. But there were no images of the Battle of Khe Sanh on the cover of Life that week, or of the ongoing Tet Offensive, or the recent attack on the American embassy in Saigon, or of Kosygin or Brezhnev or McNamara or Johnson, or of any of the other people and events weighing so heavily on the minds of Americans that winter: there was only a beautiful young girl making her country proud. It was a feat for which she would be handsomely rewarded for the rest of her life.

Now Nancy seemed poised to inherit her crown. She was just as elegant, just as humble, just as stylish, and just as graceful. She was also just as steely a competitor as Peggy had once been, and concealed the same athletic rigor beneath the same veneer of girlish charm, but that was, perhaps, best left unexamined. More important than her skill or her strength or her contributions to the sport, Nancy could make Olympic audiences feel good about being American. Nancy Kerrigan was growing more and more famous simply for being Nancy Kerrigan. And she was also coming to learn, just as Tonya was, that there were certain exceptions to the sport’s rules. Being a winner could make you lovable, but being lovable, it seemed, might also be enough to make you a winner.

Nancy’s family—her gruff but devoted father; her blind mother, whose tough-as-nails and Southie-inflected voice softened only when she spoke of her daughter; and her two boisterous, hockey-playing older brothers—was just as easy to love. When Nancy went to Albertville, all the Kerrigans went with her. Interviewed for the New York Times, Nancy’s mother, Brenda, recalled her daughter’s reluctance to go back to the Olympic Village with the other athletes: “She asked if it was OK. Of course it was OK; this is her time to be with the other kids. Nancy is always so apologetic. I don’t want to say she’s a perfect child… but she’s a caring child who loves family.” Nancy, the twenty-two-year-old baby of the family, still lived with her parents in the same modest green house in which she had grown up. When she traveled to competitions, she shared a hotel room with her parents. She didn’t have much time for friends or dating, and didn’t seem to have much interest in either, describing her mother as her best friend. Nancy’s mounting success was a victory not just for her, or even for the Kerrigans, but for a way of life Americans feared was fast shrinking: that of the wholesome, hardscrabble working-class clan. One network profile showed Nancy brushing her mother’s hair. Another showed the Kerrigan family seated around the dinner table, toasting each other with glasses of milk.

But if Nancy got to be a working-class hero worthy of a Horatio Alger story, Tonya had to be pressed into service as her counterpart, and as one of America’s most reviled demographics: white trash. In the weeks and months following the scandal, a new variety of sports journalism emerged that could perhaps most aptly be called the Tonya-bash. It was an easy form to learn, about as simple as a Mad Lib, but far more enjoyable, and almost impossible to avoid. Once an author set down one anecdote or piece of biographical information, he had to add one more, and then another. There seemed to be a greasy, eventually shameful pleasure that came with both writing and reading about not just Tonya’s gaffes or problems but the basic facts of her existence. Her mother had been married six times to six different men, or maybe seven, depending on the journalist’s sources. Tonya owned her first rifle, a .22, when she was still in kindergarten, and had moved thirteen times by fifth grade. She dropped out of high school at fifteen. (In fact, she later obtained a GED.) She drank beer and played pool and smoked even though she had asthma. She raced cars at Portland International Raceway, and was involved in a much-hyped traffic altercation in 1992, when she brandished a Wiffle-ball bat at another driver (reported, inevitably, as a Louisville Slugger). She skated to songs like Tone Lōc’s “Wild Thing” and LaTour’s “People Are Still Having Sex.” She was ordered to change her free-skate costume at the 1994 Nationals because the judges deemed it too risqué. Her sister was a prostitute. Her father was largely unemployed, as was her mother, as was her ex-husband. No matter how journalists added up the details, however, they all seemed to reveal the same motive: Tonya was going nowhere fast, and she had decided to take Nancy with her.

*

Somehow, in the scandal’s aftermath, the form of the Tonya-bash was able to alchemize even the most chilling details of Tonya’s life into tabloid gold. In a Rolling Stone article published shortly after the scandal, Randall Sullivan chronicled a visit to the Tonya Harding Fan Club, where he met “the [club] newsletter’s editor, Joe Haran, a puffy Vietnam vet with white hair and spooky eyes, [who] said he identified with Tonya through his memories of abuse and poverty suffered as a child. Haran was someone for whom it was not inconceivable that a world-class figure skater might phone the police, as Tonya Harding did in March of 1993, to report that her husband, Jeff Gillooly, had emphasized himself during an argument by slamming her head into the bathroom floor.” More than anything, it seemed, Tonya’s history of abuse proved that she didn’t belong in the world whose acceptance she so craved.

Yet her biography was nothing if not malleable. When Tonya first rocketed to fame by landing the triple axel in 1991, the media had tried to put a more positive—and more salable—slant on her lifestyle, using the same information, which they would later call in as proof of her trashiness, to paint a picture of a spunky, all-American tomboy. In the words of one profile piece, “She’s only five feet one inch… and weighs only ninety-five pounds. But as petite as she is, there’s a tomboy streak in her that she’s proud of. She drives a truck and tinkers with her car… Yet there’s clearly a young lady coming through in her skating, and her personality.” In 1991, the skating world had no choice but to try to love Tonya: she had done what no other American woman could, and if she continued to grow as a skater—and continued to act more and more like “a young lady”—she could make her country proud at the Olympics, and earn both its love and its money.

Back then, she also didn’t need stories of ladylike behavior and quirky tomboyishness to convince her audience that she was worth believing in. At the pinnacle of her career, Tonya was, in a word, spectacular. At the time, the only other woman who had landed the axel was Midori Ito of Japan. Midori was a remarkable jumper, and she made the axel look effortless: launching all four feet nine inches of herself into the air, her body seemed light, buoyant, and meant for flight. Tonya’s axel did not look effortless. It did not even look beautiful. It looked difficult—which, of course, it was.

The axel is the only jump that a skater executes by facing forward and taking off from the front of the skate, but like all other jumps it is landed backward. The skater, having taken off from a position that makes gaining the necessary height that much harder, must also somehow squeeze out another half rotation while she’s in the air. Then she has to land it. Completing three and a half rotations in midair is far from easy, but even more difficult is coming back to the ice with all the speed, power, and momentum you need in order to leave it, to somehow land steadily, and to continue with your routine.

Tonya was tiny, but her presence on the ice was powerful, undeniably muscular, and impossible to ignore. Commentators like to talk about skaters “fighting for each jump”; Tonya seemed to fight the jumps themselves. Later, much would be made in both the press and in parody about Tonya’s thighs: they were huge! They were so fat! How could she pretend to be pretty, or even feminine? But they were, at the end of the day, nothing more or less than the thighs of an athlete. They were thick and powerful because she needed them to be that way to launch herself into the air. When Midori jumped, she seemed to float like a leaf borne on the wind. Tonya, Time magazine wrote during the scandal, “bullies gravity.” They meant it as a criticism of her skating, and, by extension, of her, but one wonders: did this have to be a bad thing? What was inherently wrong with a spectacle of female power in which you could almost taste the athlete’s sweat, and feel her desire, her soreness, and her determination to leave the ground? She wasn’t artful, but it wasn’t her job to make art; she wasn’t soft and feminine, but it wasn’t her job to be those things, to sit still, or to smile passively while the cameras lingered on her face. It was her job to jump and spin, to tear the ice with her speed, to fight and fall and get up and fight again. And for a while—when the axel was a novelty and her country needed a skater who could challenge the Japanese, when the old narrative of American spunk versus a foreign juggernaut was ready to be dusted off for yet another Olympic year, and when Tonya could be counted on to win—the axel was enough to make Tonya enough. For a moment, everything seemed within her reach.

When Tonya took off, you were never sure if she was going to make it as far as she needed to: she struggled for every inch of clearance, and as she completed her rotations her body often tilted in the air, her physical power overwhelming her attempts to control it. Sometimes she seemed impossibly tilted, and still, somehow, she was able to dig her skate in and swing her free leg as hard as she could as a counterbalance, saving her landing and skating on. Sometimes she wasn’t. Increasingly, she wasn’t. And eventually it seemed she had lost the ability to land the jump at all.

After the 1992 Olympics, at which Tonya had fallen on both her axel attempts—sliding painfully across the ice and receiving a 0.5 deduction from each judge—she stopped constructing her programs around the jump and began working on the kind of elegance and artistry that had eluded her for so long. In an interview later that year, she suggested, hopefully, that this would be enough: “I still have all the jumps without the triple axel right now, and I have more style… I mean, if other people can do it without a triple axel, why can’t I?”

But if Tonya couldn’t bring the axel, we weren’t interested. She wasn’t rewarded for working on her artistic impression, and no one cared if she landed a triple lutz or a triple-triple combination that would have garnered high praise for any other competitor. She tried to remake herself as a skater, and perhaps it was when it became clear to her that this wasn’t enough—that it was the axel, and not Tonya herself, that the people loved—that she began to have real trouble competing. It was all too easy for the skating community to write her off as a once-promising has-been: the sport, after all, was littered with them. Tonya gained weight, and began replacing even her easiest triple jumps with doubles. She started competing under the name Tonya Harding-Gillooly, then divorced her husband in 1993, only to reconcile with him soon after. Later, when it came time to fit her life story into the scandal’s narrative, journalists delighted in using this detail as proof of Tonya’s tackiness. Despite her allegations of abuse, despite the restraining orders and 911 calls she placed, and despite her claims that she feared for her life both before and after the assault on Nancy, few phrases had quite the same cachet, or were quite so gleefully suggestive as white-trash lifestyle, as live-in ex-husband.

As the quickly accepted press narrative also had it, the assault on Nancy Kerrigan was only a hop, skip, and a failed jump away from Tonya’s disappointment at the 1992 Games and her growing frustration thereafter. She was trash: trash cheats. Trash wants reward without working. Trash is dangerous. Trash doesn’t care about other people’s dreams. Why question a story that made such easy sense, and provided so much to laugh at along the way?

*

The only thing missing from the media accounts of Tonya’s life was her own version of the story, and it would remain missing for a very long time. For a period in the late ’90s, Tonya worked with ghostwriter Lynda Prouse on a memoir, but for various reasons the project fell apart and wasn’t released until 2008, when a small press published a collection of the interviews that were to have formed the basis of the book. The collection, titled The Tonya Tapes, met with very little fanfare and even less in the way of sales, despite the fact that it provided something the public had been missing for nearly fifteen years: Tonya’s own detailed account of her life and her role in the scandal. The picture she painted of her role in the assault—or rather, her lack thereof—was shocking not so much for its deviations from the publicly accepted image of her as for its unsettling plausibility.

In the interviews, Tonya described her mother using her skating trophies to store loose change, calling her fat and ugly, gulping down a thermos full of brandy as she drove Tonya to the rink in the morning, and hitting her or sending her to her room without dinner as punishment for a bad skate, preparing Tonya for the relationship she would eventually have with her husband. “My mom hit me, and she loved me,” Tonya recalled thinking. “[Jeff] hits me, he loves me. It’s just the way life goes.” She described marrying Jeff—at the time the only man she had ever dated—at nineteen, largely because she was so desperate to get out of her mother’s house. She described her half brother—who was later arrested for child molestation—attempting to rape her when she was fifteen, and how her mother refused to let her testify against him. She described Jeff’s abuse—abuse that was corroborated by her friends and by police reports available to the press at the time of the scandal, but generally utilized only as proof of Tonya’s trashiness—and how neither her family nor her coach was willing to believe her claims. She described leaving Jeff and coming back to him, leaving him again and coming back again, because he was “always saying the right things to get me back, and I’d be stupid enough to go back and get beat up again.” As with so many other women at the center of a scandal, the media did an exceptionally good job of selling Tonya as an extraordinary specimen, a woman unique in her shamelessness, greed, and brutality. Her talent aside, however, she was not unusual at all, but merely one of the countless American women attempting to escape, or at least endure, an abusive marriage. Her relationship with Jeff may have become famous for its explosive ending, but it was identical to millions of others unfolding without the aid of tabloid headlines or prime-time specials.

In the book, Tonya also maintained her innocence in the scandal’s planning, telling a version of the story that seemed just as plausible as the one that had quickly gained acceptance during the event’s coverage. She said she had attempted reconciliation with Jeff following their divorce, in 1993, because a representative from the United States Figure Skating Association told her to do so “unless I didn’t want the marks. If I wanted to make the Olympic team, I need to make myself a stable life… They said I had a stable life when I was with him—married, settled down… And they wanted to make sure I was still going to be that way to go to the Olympic Games.”

In a sport where judges routinely give skaters criticism on their hairdos and costumes and earrings and eye makeup and teeth (and suggest that failing to change such details might well result in lowered scores); in a sport where, to this day, very few gay male skaters can afford to be openly gay and deal with inevitable backlash not just in the media but in their scores; in a sport where women are sometimes rewarded more for salability than skill; in a sport where gender roles are policed so rigidly, on and off the ice, that Tonya Harding, a petite, blond, white woman, was somehow butch enough to register as a threat to skating’s femininity—in a sport where all this went on, and was in fact common knowledge, the idea that the USFSA would attempt to control a skater’s marital status is hardly implausible. It wanted Tonya to be proper, or at least as proper as she could be. They wanted her to train hard and skate reliably so she could compete well at the Olympics if she remained the only American skater who could match Nancy’s maturity and skill—a very plausible prospect at the time, even if the USFSA didn’t want to admit it. If the representative Tonya says she spoke to had been aware of Jeff’s abuse, there must have seemed too much at stake to give Tonya’s claims much credence. Tonya was abused by her mother, her husband, and finally her sport, whose criticisms of her—she wasn’t pretty; she was too fat; she didn’t deserve to be here; why couldn’t she do anything right?—savagely echoed the criticism she had been enduring for her entire life.

In discussing her failure to come forward upon finding out about Jeff’s role in the assault after the fact—the only crime of which she was eventually convicted—Tonya said that Jeff’s abuse had only grown more severe following the attack on Nancy. He had put the plot in motion, she believed, because he was angry that she had reunited with him only at the USFSA’s request, and that she planned to leave him as soon as she had competed at the Games. “When he found out,” she said, “he came unglued… He told me he’d ruin me.” If this really was his plan, he could hardly have been more successful.

After the attack, Tonya told her interviewer, Jeff decided to threaten her by holding a gun to her head, letting two other men rape her, and then raping her himself, telling her he would kill her if she took her story to the FBI. Even if one finds reason to disbelieve this claim, Tonya’s history of abuse, her justifiable lack of trust in authority figures, and her equally justifiable fear of how the public might treat her if she came forward with what she knew all make her failure to act seem perfectly fathomable.

As for Tonya’s claims about her own innocence in the plot itself, any attempt to dismiss her version out of hand somewhat falls apart once one realizes that the dominant version of the story—the story the press picked up and popularized, and the story that endured largely for that reason—was Jeff’s. Tonya’s version of events is implausible only because it contradicts the story we’ve been familiar with for the last twenty years. Telling it nearly fifteen years after the scandal took place, she also had far less of a reason to lie than Jeff did while he was still trying to strike a deal with the prosecution. Eugene Saunders, the pastor to whom Shawn Eckhardt confessed his role in the plot, told the press that Shawn made it seem as if Tonya had been uninvolved in planning the assault. Shawn had said the same when he was first interviewed by the FBI, and though he changed his story later, the backpedaling testimony of a scared would-be hit man hardly seems as unimpeachable as the public made it out to be.

Beyond Jeff’s, and, eventually, Shawn’s testimony, there was relatively little to link Tonya to the attack’s planning at all. The only involvement Tonya had that could be corroborated by any witnesses beyond Jeff, Shawn, Shane, and Derrick was insignificant: she called a friend who wrote for American Skating World to find out where Nancy practiced, saying she had a bet with Jeff; she went along to Shawn’s house when Jeff delivered the information on Nancy and the up-front pay Shawn had requested before the attack, but stayed downstairs, making small talk with Shawn’s mother; and she asked for Nancy’s room number from the desk clerk at the Detroit Westin where she and Nancy were both staying during the US Championships. These instances were enough to arouse suspicion, but were hardly damning. Jeff could, in fact, have made a bet with Tonya as to where Nancy skated, and she could have found out what he needed without suspecting he planned to put the information to such a use. She was also likely used to waiting around at Shawn’s house while he and Jeff played at being assassins, and when questioned as to why she had asked for Nancy’s room number, she later claimed that she had wanted to slip a poster under the door so Nancy could autograph it for Tonya’s friend and fan-club founder, Elaine Stamm. This wasn’t especially unlikely behavior for Tonya, who, despite the press’s seemingly endless reports of her anger issues, tantrums, and ruthless competitiveness, had always been friendly with Nancy, and made an effort to keep things that way even as the scandal progressed.

She was also remarkably good-natured in her dealings with the press for the weeks leading up to the Olympics, but even her politeness and positive attitude could easily be used against her: saying it had always been “her dream” to return to the Olympics meant she didn’t care whom she had to step on to get there, or at the very least that she was deeply delusional. Being kind to the press meant she craved its attention no matter what the cost. And attempting to show kindness to Nancy, as she did when she said she wanted to give her a hug on her arrival at the Olympic Village, was the worst of all. The media had a field day with the statement, suggesting it was further proof of Tonya’s cold-blooded intimidation tactics—a hug from Tonya, the newscasters’ arch tones suggested, would no doubt have involved a knife between the ribs—but it could also be read as the well-meaning suggestion of a woman who desperately wanted to act as if nothing was wrong, and who believed, more than a little naively, that she might still be able to convince the world, or at least her alleged victim, of her innocence. By then, however, it was far too late. Nancy declined the offer, and the two women never actually spoke for the duration of the Games.

*

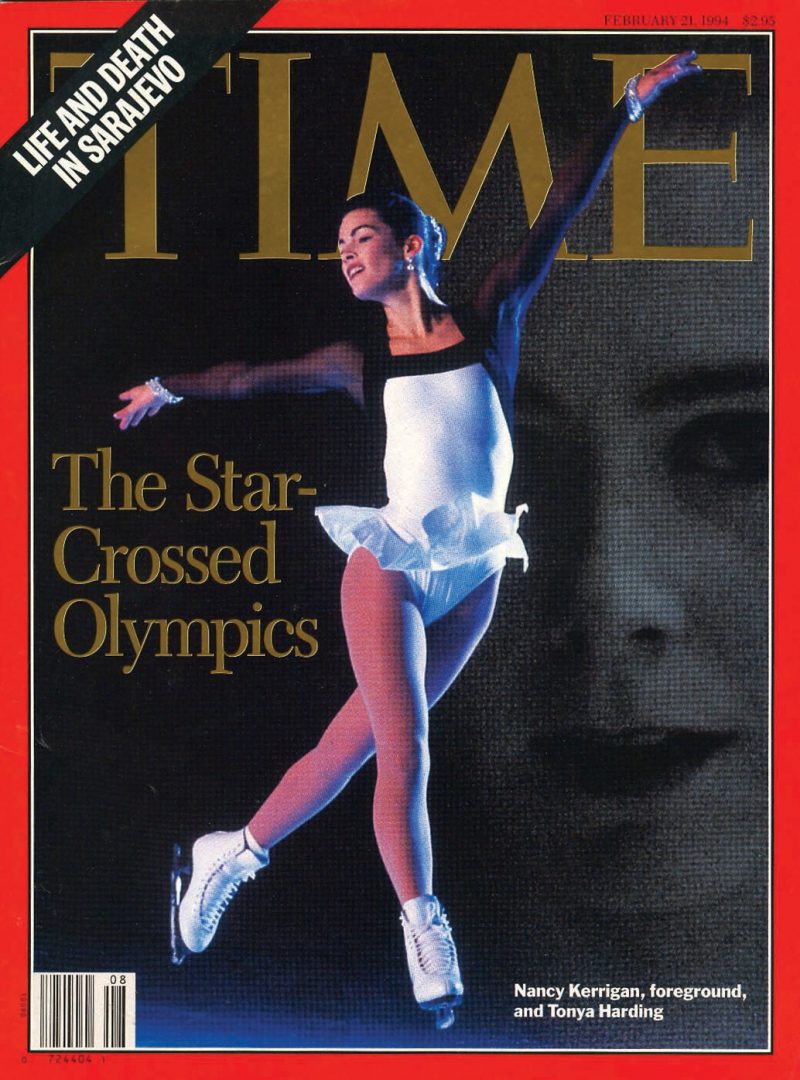

Tonya had famously arrived late to the 1992 Olympics, but she was right on time in 1994. Her ability to compete at the Games despite the mounting suspicions against her seemed, to viewers, both an affront to decency and sportsmanship and an unimaginable boon. Something was coming—something good. In the six weeks since the attack, media coverage of the scandal had built Tonya up from a somewhat tactless young woman into a bloodthirsty fiend; when she and Nancy appeared together on the ice for the first time after the assault, their practice session was glutted with reporters, the constant snapping of the cameras’ shutters sounding like nothing so much as the shuffling and reshuffling of a deck of cards.

But whatever reporters had been hoping for—accusations, hair-pulling, a bloodbath right there on the ice—didn’t happen. The conflict, it seemed, could be resolved only through competition, a belief widespread enough to make the ladies’ short program the fifth most watched television broadcast of all time. Forty-five million viewers in the United States alone tuned in to watch Tonya deliver a lackluster skate, seeming strained and exhausted in a glittery red costume. She was in tenth place at the end of the night, while Nancy, skating cleanly, and looking calm and happy to be on the ice, easily glided into first place. Anyone who wasn’t on tenterhooks as they waited for a confrontation between Tonya and Nancy may have noticed an impossibly polished performance turned in by an impossibly young skater named Oksana Baiul. But forty-five million Americans didn’t sit through a ladies’ figure skating competition just to watch some ladies figure skate. They wanted anger, screaming, tears. And if an actual fight was impossible, they at least wanted more of what had made the scandal itself so compelling: the spectacle of female pain.

Three days later, when Tonya’s name appeared on the marquee to announce the beginning of her free skate, her audience was ready for her, but Tonya wasn’t ready for them. Her lace had broken during the warm-up, and now she couldn’t find a replacement: because of her jumps, Tonya’s skates were specially designed, and required longer laces than those other female skaters used. As Tonya tried to make do with a regular lace, the clock ticked down the seconds she had to appear on the ice before being automatically disqualified. The arena audience waited, confused, while the audience at home watched Tonya backstage, the cluster of people around her growing, her expression inscrutable in the murky light.

Tonya made it onto the ice with seconds to spare, went into her opening jump—a triple lutz—and completed only a single rotation. Not just her jump but her body seemed to come apart in the air, her legs and arms splaying toward opposite points as she froze for a moment above the ice, looking almost as if she was about to be drawn and quartered—which, in a very real sense, she was. She landed, looked down at her skate, and attempted to continue, but a few seconds later, as her music came to a fluttering crescendo, she dropped her head and began to sob. After making her way over to the judges’ table, she lifted her skate up to show them her lace, her lucky gold skate blades glinting in the stadium lights.

Tonya had done everything the protocol demanded: in such an event it was a skater’s job to go to the judges, tell them what was wrong, and get permission to fix it. Later, her problems would be overwhelmingly presented as a last-minute ploy for attention and the second chance she didn’t deserve. Anyone who had watched her historic performance at Skate America in 1991, however—the event at which she had landed two of the best triple axels of her career—would know she had dealt with the same issues years before. Leaving the ice after her flawless free program at Skate America, Tonya, screaming with joy, plowed into her coach’s arms. The last words the cameras picked up from her before the commercial break were the untroubled afterthoughts of a girl too flush with good fortune and newfound evidence of her own invincibility to think of anything else. “You know what?” she told her coach as she relaxed her embrace. “I broke my boot again.”

It was clear the problem was one she had dealt with for years, and that she had long ago come to realize that her sport’s equipment simply wasn’t designed to contain her strength. But that night at Skate America it didn’t matter. Despite the fact that she had broken an eyelet—and her fears that her boot wouldn’t hold her during her triples—she had skated a perfect program, and ended the night with two 6.0s for technical merit and a gold medal for the event. But on that night, the whole world was behind her, urging her to land the axel, urging her to win. Little more than two years later, Tonya took to the ice knowing that the world now wished just as fervently for her failure.

After Tonya explained that her skate lace was too short to hold her on her jumps, the judges allowed her to go backstage and fix her skate with the longer lace her coach had finally found for her, while Canadian skater Josée Chouinard took Tonya’s place in the lineup. She was a beautiful skater in all the ways Tonya wasn’t—graceful, stylish, and stunning in a Fosse-esque ensemble of pink leotard and gloves—but that night she had a hard time dragging the cameras away from Tonya as she sat backstage, coughing and staring numbly at her skate. Tonya moved several spots down in the lineup, and was greeted by more than a few jeers when she finally took to the ice. Yet anyone who had come to the stadium or turned on their TV hoping to witness one more night of Tonya performing the role of Tonya—trashy, shameless, greedy, lazy, and above all entertaining—couldn’t help feeling their appetite had only been whetted by her earlier problems. That had been the appetizer; now for the entrée. Would she try to find another excuse to get off the ice? Would she cry again? Would she fall—again, and again, and again? Would she hurt herself? Something would happen—something had to happen.

Tonya had disappointed her audience before. She had given lackluster skates, sometimes disastrous ones. She had fallen while attempting her axel or left it out entirely. She knew what it was like to let people down by skating badly. This time, though, she had let the world down by skating well. She had given them their drama for the evening, had let all the confusion and fear and anger of the last six weeks get to her when she should have been most impervious, and had let herself become, for the briefest moment, a spectacle of pain, just as Nancy had six weeks before. But now, like Nancy, she pulled herself together and faced the crowd. This time, she landed as flawless a triple lutz as she had at the US Championships, and skated with some of the same newfound grace and maturity she had displayed there not so long ago. Her triple axel was gone: she would never land it in competition again, would never compete again, and she knew it. But she took her time, seeming to savor the feeling of being out there, of having made it to the Olympic ice at all, and of being able to do, just one last time, the only thing she had ever been great at, and the only thing she had ever loved that had loved her equally in return.

Writing about Tonya’s insistence on skating, Christine Brennan argued that “she had every right under US law to skate in Norway. But the responsible thing would have been for Harding to gracefully withdraw.” Yet if Tonya had to be painted as shameless—and after the last six weeks there was no other role she could play—she could at least put her supposed shamelessness to good use. If the judges she had tried so hard to please had never been able to find any gracefulness in her skating, then why did she have to conduct herself gracefully now? And why—at the end of a career in which everything she did, every role she was allowed to play, and every achievement she was considered capable of was dependent on other skaters—did this moment have to be about anyone but her? She had refused to slink away when the public wanted her to buckle under the pressure not of competition but of humiliation. She had spent her entire life struggling to deliver the performance that was expected of her. Now, expected to do the easiest thing there was—to fall apart on the ice, to be weak, punished, and ashamed—she rebelled, and did the hardest thing that not just she but any woman performing that night could have: she skated the way she wanted to. She finished the Games in eighth place, but in her own way, and on her own terms, she had won.

*

Reporting from the wreckage of the scandal’s aftermath, journalists would make much of the fact that Tonya had skated her free program to the theme from Jurassic Park. The New York Times suggested she may have felt “that if fictional dinosaurs can be resurrected, so can her career.” Extinction jokes abounded. Beyond the subject matter, authors implied, it was the sort of tacky and unfeminine choice one could expect from Tonya. (Meanwhile, former Olympic champion Katarina Witt didn’t seem to inspire any flak for skating to the theme from Robin Hood: Prince of Thieves, clad in a tunic and breeches and including a mimed bow and arrow in her choreography.) In Women on Ice, an anthology on the scandal released the following year, Stacey D’Erasmo took a more sympathetic approach, writing that “watching Tonya walk barefoot up and down that long, dark corridor Friday night as the other women in their shiny little outfits passed her by, then watching her skate to the music of Jurassic Park, a movie about extinct animals, I felt that I was witnessing the final act of an American tragedy.”

Yet D’Erasmo, for her embrace of the moment’s pathos, still somewhat missed the point. Watching the Olympics that night, viewers witnessed not just the end of Tonya’s career but the extinction of a whole era of ladies’ figure skating. If Tonya was a T. Rex, lumbering out of her enclosure and bringing chaos to the night’s well-ordered spectacle of heavily regulated female strength, then Nancy was a velociraptor, hissing with stifled aggression as her turf was overrun by tiny, quick-blooded mammals. As Nancy warmed up with the final group, she found herself surrounded by teenagers: Tonya may have famously trained in a mall, but Nancy had to compete against girls who looked like they would have been more at home shopping in one. Nancy delivered a beautiful routine that night, elegant, nervy, and technically flawless. But it was also the skating of a grown woman, and she narrowly lost both the gold medal and the crowd’s favor to Oksana Baiul, the bubbly, crowd-pleasing sixteen-year-old orphan in pink marabou. However much the public had tried to situate Tonya and Nancy as enemies, they remained united, if only in their representation of the sport’s old guard, and of the last gasp of a period during which skaters could just possibly be seen as women and not as girls.

After the Games, Nancy lingered in the spotlight just long enough to see public opinion turn incongruously against her, a phenomenon that might have seemed no stranger to her than the sudden adulation she had recently been the subject of. The process began mere minutes after Nancy skated, as she waited to take her place on the podium. She was ready to receive her medal, and most likely to go home and turn her back on the events of both that night and the previous six weeks, but Oksana was still backstage. As it turned out later, no one could find the copy of the Ukrainian National Anthem they would need to play during the medal ceremony, but at the time Nancy was misinformed that Oksana was having her makeup done, to which she groused, “Oh, come on. So she’s going to get out here and cry again. What’s the difference? It’s stupid.” Was Nancy—radiant Nancy, good Nancy, Nancy who just wanted to go out and skate for herself—being competitive? Was it possible that she was being not just competitive but bitter?

It was. In fact, Nancy seemed to be irritated not just about her loss to Oksana but about—well—us. Soon after the Games, in a homecoming parade at Disney World in which Nancy stood on a float with a Mickey Mouse–costumed employee, wearing her silver medal and a weary smile, she complained: “This is so corny. This is so dumb. I hate it. This is the most corny thing I’ve ever done.” Mickey shrugged mutely. The rules he obeyed while wearing his costume didn’t allow him to say anything, but the rules Nancy had to follow didn’t let her say much more.

Yet the public had an even stronger motivation for its newfound distaste: Nancy had failed. She hadn’t won the silver. She had lost the gold. How, after miraculously recovering from her injuries (which were in fact relatively minor), after training harder than she ever had before, and after gaining the adoration of her country, if not the world—how, after all this, could she fail? She was skating not just for herself but for us, for middle America, for goodness, for sportsmanship, for proper femininity, and she was propelled by the strength of our needs and desires. Wasn’t that enough?

But Nancy’s lack of adherence to her role soon faded into memory: someone had to play the victim, and television abhors a void. Tonya and Nancy reverted back to their old roles within the public eye, and for the next few years wandered in and out of newspaper and tabloid pages with declining frequency. Whenever they turned up, however, they were considerate enough to do what was expected of them. Nancy continued to perform in ice shows and TV specials; Tonya was banned from the sport. Nancy married and had two children; Tonya married her second husband, then had her second divorce. Nancy started the Nancy Kerrigan Foundation and was named as the spokesperson for the Foundation Fighting Blindness; Tonya completed a court-ordered five hundred hours of community service. Their sport went on without them, and teenagers continued to flood the rinks.

Shortly after the Olympics, in the kind of surreal moment Tonya’s career would contain far too many of, Woody Allen briefly considered her for a role in Mighty Aphrodite, but gave up on the idea when he learned that her probation prohibited her from leaving the West Coast. Instead, Tonya made her film debut alongside Joe Estevez in a low-budget 1996 thriller called Breakaway, which earned her ten thousand dollars and a lot of ribbing from the press. The gimmick casting didn’t sell many tickets, but Bill Higgins, the film’s unofficial Tonya-sitter, was still able to sell the story to Premiere magazine. He recalled Tonya’s on-set diet of fifty-nine-cent Taco Bell bean burritos, orange soda, and Benson & Hedges 100s; her wonder at the sight of Aaron Spelling’s fifty-four-thousand-square-foot mansion (“Now that’s cool”); her requests to go to Disneyland; and her state of denial, well after her lifelong ban from competitive figure skating and her unofficial ban from exhibition skating and ice shows, as to what life held for her. Acting, she said, was “really fun,” and “the action part,” when she got to beat up a man twice her size, “was really cool,” but as a career it wasn’t for her: “I had, and still have, my career,” she said, “and that’s skating.” Then, scaling back her ambition a bit, she added, “If they do a movie of my life, I would just like to do the skating. Nobody skates like I do.”

She was right. No one did, and in the last twenty years, no one has. Since Tonya became the second woman in the world to land a triple axel in competition, only four others have managed to follow her: Ludmila Nelidina of Russia, Yukari Nakano and Mao Asada of Japan, and Kimmie Meissner of the United States, who landed a triple axel for the first time at the 2005 US Championships, which were held that year, coincidentally, in Portland, Oregon. The women who came after Tonya struggled, much as their predecessor had, to understand how best to use their strength in a sport that had never quite learned what to make of it, let alone whether or not to reward them for it. Neither Yukari Nakano nor Ludmila Nelidina ever medaled at Worlds or made it onto an Olympic team, nor did they rocket to the sort of fame they might have imagined would accompany such a feat. Kimmie Meissner came in sixth at the 2006 Olympics and won a gold medal in the World Championships a few weeks later, but, like Tonya, she had trouble hanging on to her axel, and she was forced into retirement by a string of injuries before she had a chance to compete at another Games. Present at the 2010 Olympics, however, was Mao Asada, who planned—and gorgeously executed—a record-setting two triple axels in her free skate. She had hoped that they would help her to beat Yuna Kim, whose elegance and beauty on and off the ice had made her a favorite for the gold and a millionaire in her native South Korea before the games had even begun. They weren’t. Mao Asada came in second, but anyone familiar with the narratives of figure skating knew what had really happened: she hadn’t won the silver. She had lost the gold.

*

Clackamas County, Oregon, the roughshod collection of edge cities, mini-malls, and farmland whose communities Tonya shuttled between throughout much of her life—Happy Valley to Milwaukie, Lents to Beavercreek, Oak Grove to Estacada—hasn’t changed much since its fabled daughter’s girlhood. The areas closest to Portland have seen the crowding and expansion that came with the city’s growth into a legitimate metropolitan area: driving from the city center into Clackamas County, you will pass the new-car dealerships and strip malls and condo developments whose signs promise if you lived here, you’d be home by now. But you don’t have to drive far to get beyond the suburban sprawl and into the past. There, as in 1994, you will find ranches and ranch houses; towns with names like Boring and Needy, which don’t so much invite mockery as head it off at the first pass; and roadside farm stands and U-Pick outfits that, in the summertime, erect signs telling motorists WE HAVE BERRIES: BLACKS AND BLUES.

It is a place of freeway exits and depressed communities and temporary living, but it is also a place filled with surprising beauty, home to protected rivers and forests, and so close to Mount Hood that the snow visible on the face of the mountain seems capable of falling straight into people’s yards. It is the sort of place where a young girl whose early life has conspired to make her feel worthless might find comfort and happiness fishing and hunting, splitting wood and fixing cars, and proving that she can be as strong as any boy. It is a place where a girl might learn to rely on her talent and determination rather than her looks, and in that sense it is not an unlikely breeding ground for an Olympic athlete, but it is, perhaps, the most natural place in the world for one to grow up. And if another such athlete comes from this place, and has less experience than her competitors at posing for the cameras, smiling for the crowd, and learning to hide all the desire and effort that go into her sport, one can only hope that she will not be punished quite so harshly as her predecessor.

The rink at Clackamas Town Center, where Tonya Harding learned to skate—and which, Susan Orlean wrote during the scandal, was “the only place in America where an Olympic contender trains within sight of the Steak Escape, Let’s Talk Turkey, Hot Dog on a Stick, and Chick-fil-A”—is now long gone, and the Town Center, once the headquarters of the Tonya Harding Fan Club, has removed all traces of its famous former tenant. But if you venture into Portland’s Lloyd Center mall, you can still find the rink where Tonya skated for the first time. She was not quite three years old. “They had this archway with bars in it,” she recalled fondly, nearly thirty years later, “and there was an ice rink down below. We were walking across it—my mom and me and her son, and I said I wanted to do that, and she said no… I sat down and started screaming… I had a fit. And I guess they said, ‘OK, fine.’ Went down, put some skates on me, and I sat down on the ice, and I kicked at it and picked it up and was eating it. They told me not to do that because it was bad for me and that I had to get up and do what everybody else was doing. And so I did. I got up and skated around. After that, I told them I liked it and wanted to do it more… I told them this was what I wanted to do.” And so she did. Tonya had her first skating lesson on her third birthday, and didn’t stop skating for the next twenty years. And though in that time she would spend thousands of hours learning to do what everybody else was doing—executing pretty spiral sequences and ornate choreography, doing her best to hide her strength and her sweat, smiling for the cameras and the crowds—her instincts would never really change. For the next twenty years, every time Tonya entered the rink, she was guided by the same desire she had felt that first time: to tear the ice’s perfect, shining surface apart, and make her presence known.