In 1915, long before the release of Spinal Tap, and longer still before sculptor Anish Kapoor purchased the rights to Vantablack, the Polish Russian artist Kazimir Malevich first exhibited Black Square in Saint Petersburg, at The Last Futurist Exhibition of Paintings 0,10 (called simply “zero-ten”). The number indicated a “point zero” for a new arts movement, suprematism—from whence all possibility might begin—and for the ten featured artists. “Up until now… painting was the aesthetic side of a thing, but never was original and an end in itself,” Malevich wrote in a handout accompanying the exhibition.

Malevich’s very first black square appeared in the design of a stage curtain for the production of a 1913 cubo-futurist opera called Victory Over the Sun, for which Aleksei Kruchenykh and Velimir Khlebnikov wrote the text, Mikhail Matyushin composed the music, and Malevich designed the set and costumes. Written in Zaum—a phonetic, trans-rational language created by Russian futurist poets—the work attests to the values of suprematism, setting it against the artistic movements that preceded it, as well as its utilitarian, technologically charged contemporary, Soviet constructivism. In the opera, the characters seek to abolish discursive reasoning by capturing the Sun (encasing it in concrete, to be given a lavish burial by the Strong Men of the Future) and ending time as it is known; the play culminates in an aviation catastrophe, with the world in darkness. The opera was not well received by the public at Luna Park, the amusement park in Saint Petersburg where it premiered in 1913, or by critics, but it announced the genesis of a uniquely Russian approach, one unbound by the traditions of Western Europe.

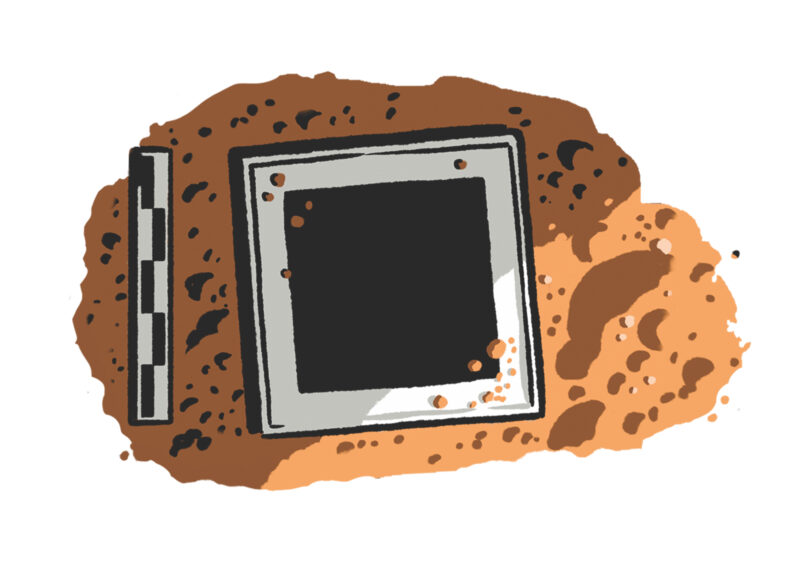

At 0,10 two years hence, the gallery-goer might first have been struck by the presentation of Black Square, in the upper right corner of the wall, at the sacred site traditionally dedicated to icons in Russian Orthodox households and known as “the red corner,” usually located in the eastern part of the building. They might have been outraged not only because of the work’s simplicity—it is a 79.5-centimeter-square canvas bordered thickly in gray and white, filled in with black paint—but because it was not even a square. Measure the piece in any direction and find nothing in the image that is truly orthogonal. Because it is not a picture of a square, per se, Black Square is free from the constraints of representation, an absolute zero.

According to Malevich, neither critics nor the Russian public understood the piece. “This was no ‘empty square’ which I had exhibited but rather the feeling of non-objectivity… Yet the general public saw in the non-objectivity of the representation the demise of art,” he wrote. His friend Matyushin (a painter as well as a composer) was especially harsh: in letters to Malevich he declared that the work demonstrated a “lack of restraint,” “lack of maturity,” “insufficient understanding,” and an “incomplete break with ‘Cubo.’” Alexandre Benois, a leading art critic of the day, “denounced Suprematism with biblical horror,” wrote Aleksandra Shatskikh in Black Square: Malevich and the Origin of Suprematism. Benois, Matyushin, and Dmitry Merezhkovsky—who referred to suprematism as “another step of the coming Boor”—maintained such opinions. This would galvanize Malevich, who found such views outdated.

The curator Andrew Spira writes that, in fact, imperfect black squares—and even rhomboids—had long existed in art, from the English physician Robert Fludd’s attempt at capturing infinity in The Metaphysical, Physical, and Technical History of the Two Worlds (from 1617, nearly three hundred years earlier), to the black Yorick-death page in Tristram Shandy (1759), to Gustave Doré’s History of Holy Russia (1854). It is not clear how many of these works were known to Malevich, but if they relied on traditional black-and-white dualism—contrasting lightness with darkness to correspond respectively to good and evil, knowledge and ignorance, heaven and hell—Malevich stated definitively that Black Square indicated the beginning of life, of possibility, of true abstraction in art.

After 0,10, Malevich would go on to compose some of his best-known works, such as the Supremus series, which reflected the optimism—utopianism—of the new Soviet era, rejecting the bourgeois constraints of cubo-futurism and expressionism. Critics and fellow artists warmed to Malevich’s theories on form and color in the years following the October Revolution. By the 1920s, he had received patronage from the Soviet government, and became a teacher at, then the director of, the Vitebsk Popular Art Institute, replacing Marc Chagall.

The death of Vladimir Lenin, the fall of Leon Trotsky, and the appointment of Joseph Stalin as general secretary of the Communist Party began to change Malevich’s work, along with his travels to Poland and Germany between 1927 and 1929, where he became acquainted with the artists of the Bauhaus, who became his champions. These adventures during Malevich’s komandirovka, or state-sanctioned professional trip, ultimately contributed to the end of his adulation in the eyes of the government, but that was not all. Around 1930, Stalin became more forceful in ridding society of noneducational, elitist, and apolitical work; in the process, Malevich lost his job, his works were seized, and he was no longer permitted to make art. Shortly afterward he was accused of being a Polish spy and was threatened with execution but was ultimately imprisoned for two months for the crime of “formalism.”

Under Stalin, formalism was an atheist’s cardinal sin: it was used to describe art that was concerned mainly with aesthetics and technique. Unlike art made in the style of social realism, formalist art did not serve the ideological or political goals of Soviet communism. Malevich’s willful abstraction and anti-representational work fell under this charge.

After his release from prison, Malevich was again permitted to paint but was forbidden to pursue abstraction: the works from the last five years of his life are increasingly representational—and often pay homage to life before the revolution—but he continued to sign his work with a black square. Black Square was featured heavily at his burial: on his arkhitekton casket, on the front grille of the hearse, and on his gravestone in the Moscow suburb of Nemchinovka, which would be destroyed during the Second World War; currently, an apartment building sits on his gravesite. In the same town, after a long battle, the Kazimir Malevich Memorial Center was demolished unceremoniously in 2019, the 140th anniversary of the artist’s birth; authorities cited the lack of title documents for the land and the building.

Alas, I have never seen Black Square in person, and geopolitics make it increasingly unlikely I ever will: it is housed at the Tretyakov Gallery in Moscow, though versions of it have traveled to the English-speaking world on several occasions. The work is incredibly fragile, due largely to its five decades of neglect in Soviet storage. When I look at images of Black Square, I see a leopard in the fine craquelure, then Koko the legendary simienne of my childhood, who had a robust vocabulary and a pet kitten called Lipstick.

In 2015, imaging specialists Irina Voronina and Ekaterina Rustamova found—in a series of X-rays, infrared scans, and high-resolution 3D surface color recordings—many mysteries to be read in the flaking material. In addition to two colorful paintings that had been painted over—one cubo-futurist composition, one proto-suprematist—they discovered Russian-language text referring to earlier works featuring black squares, including a print with a racist title by the French writer Alphonse Allais. The levels of regret, indecision, and false starts that make up an artist’s life were laid bare in new ways; indeed, this was no ordinary square of black paint.