For starters, see if you can find yourself one of those concave makeup mirrors, you know, the kind that make your face look larger than it is. Tomorrow morning, when it’s bright out but still dark in your room, go over to your window, gather all of that outside light into the mirror, and reflect it back onto the darkened interior wall next to the window. Move the mirror back and forth until the reflected image swims into focus. Pretty amazing, huh? A virtual movie, all Technicolor, of everything taking place outside, only upside down.

Now, here’s something else you can try. Pull out some art-history textbooks and photocopy a few dozen instances of paintings from each century from, oh, say, 1300 through 1800.Then shingle them chronologically along a long blank wall, Northern Europe on top, Southern Europe on the bottom. (Or else go to the library and check out David Hockney’s 2001 book Secret Knowledge, and ogle his version of this same experiment.) In 1300, the renditions of faces and postures and cityscapes are all stiff and pasty and awkward; by 1700, they’re incredibly clear and “realistic,” the perspective is “right,” the rendering assured—everything is “optically” correct. Now, when and where does the change first happen? Turns out, and it’s stunningly clear and obvious that this is so, that a huge change occurs around 1430 around Bruges. Suddenly, and with hardly any struggling to get there, several artists (Van Eyck, Campin, Memling, and presently, spreading outward, da Messina and Holbein and Bellini and Lotto) are painting startlingly clean optical images; and several of those images include in their backgrounds, also for the first time in the history of art, curved (convex) mirrors.

These were the sorts of discoveries and insights that got the artist David Hockney, presently joined by Charles Falco (a renowned optical physicist from the University of Arizona in Tucson), going. Was it indeed possible, as they took to asserting (and I for my part took to documenting in a series of articles in the New Yorker and then over the web), that painters all the way back to the fifteenth century had been deploying optical devices as aids in realizing their vision? Such a contention turns out to constitute a veritable Third Rail in art history. Never have I received so many furious ripostes to one of my pieces (and I write about Poles and Jews!).

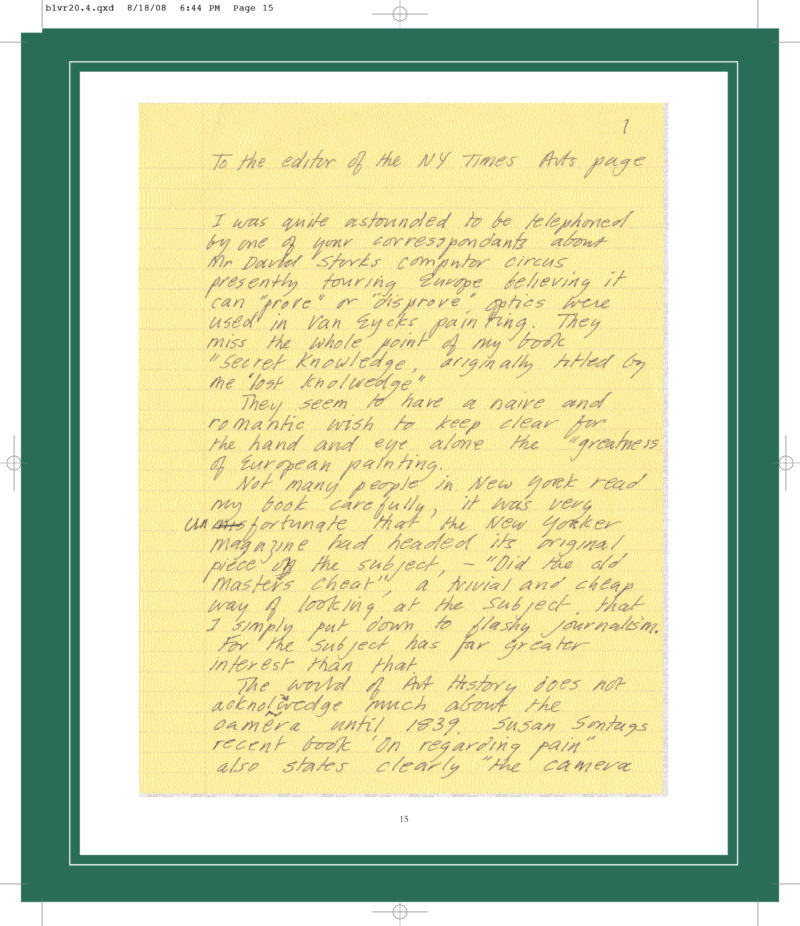

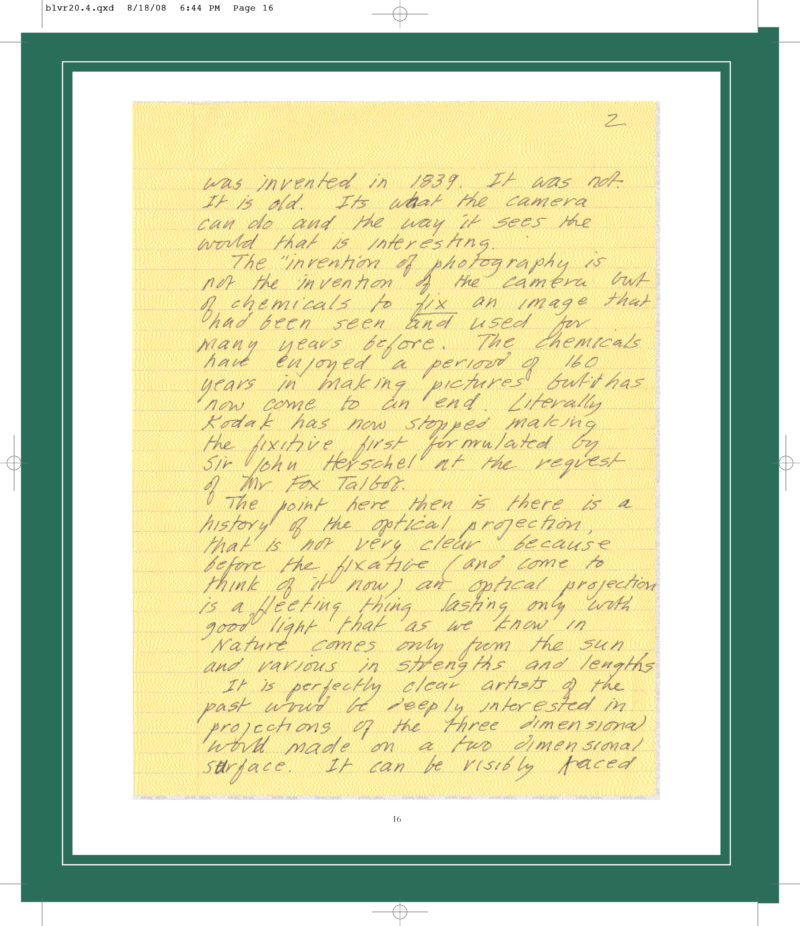

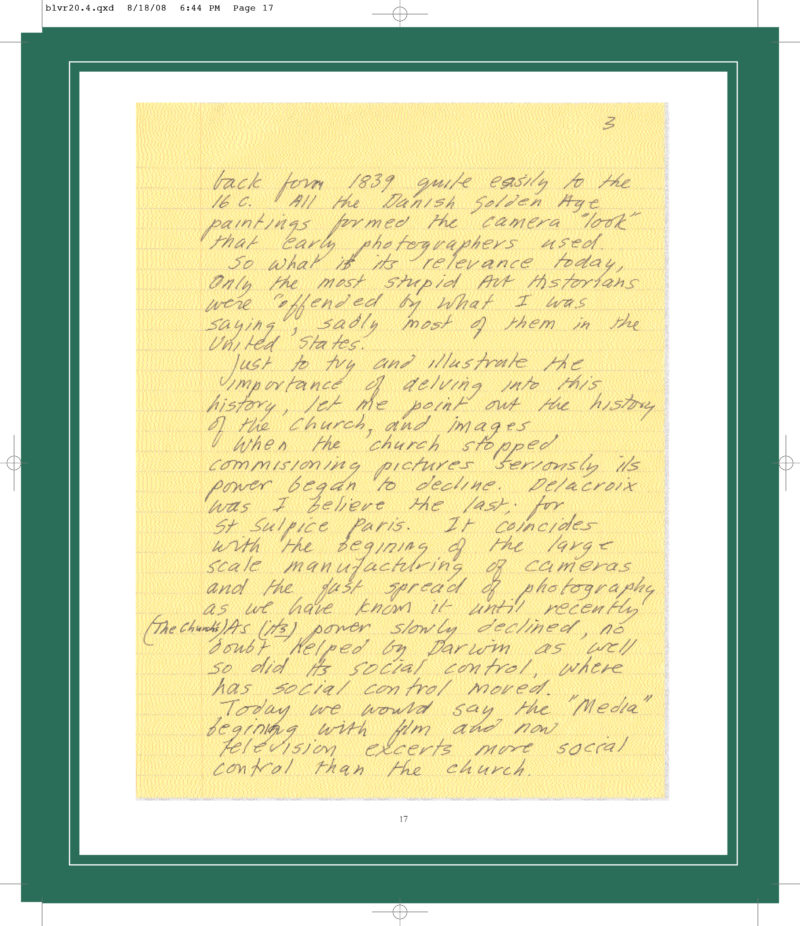

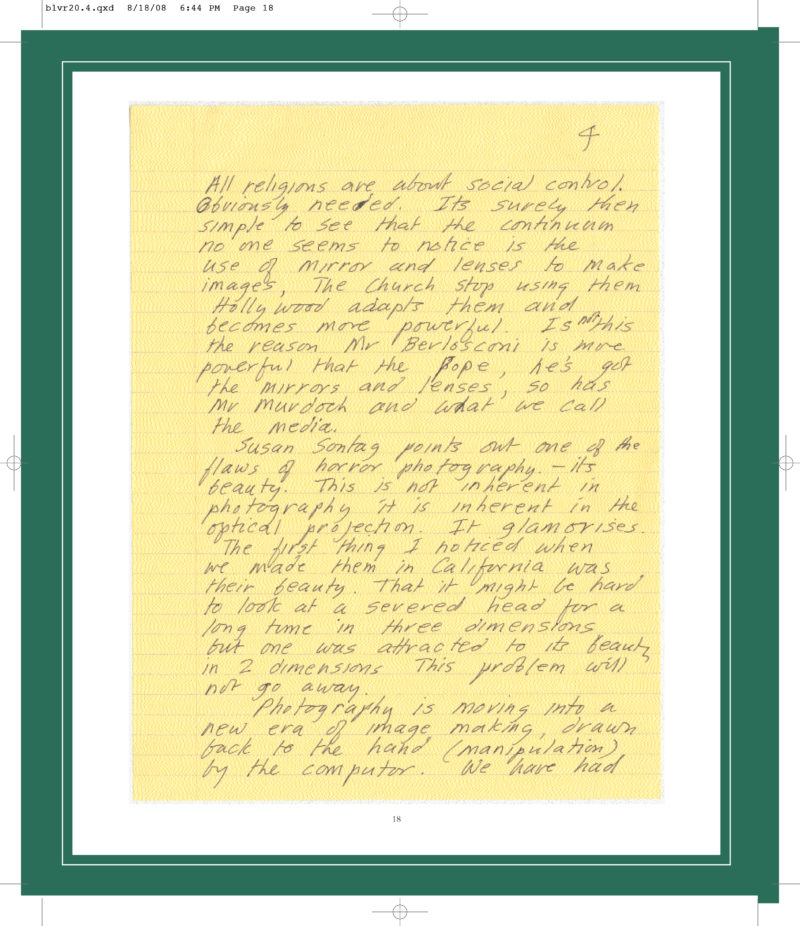

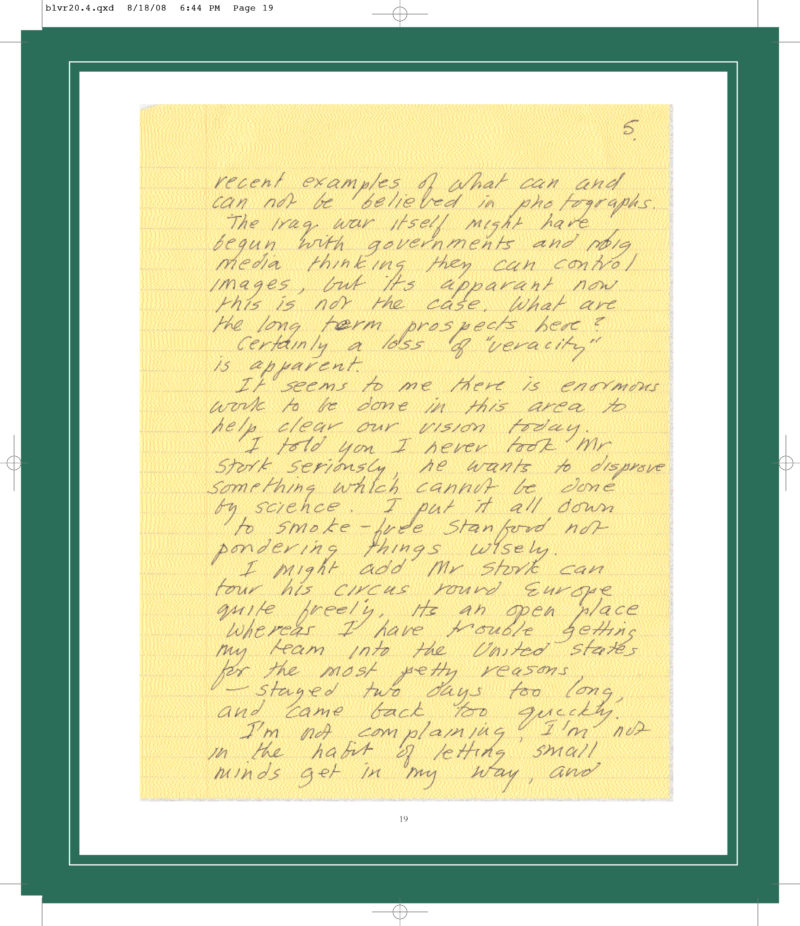

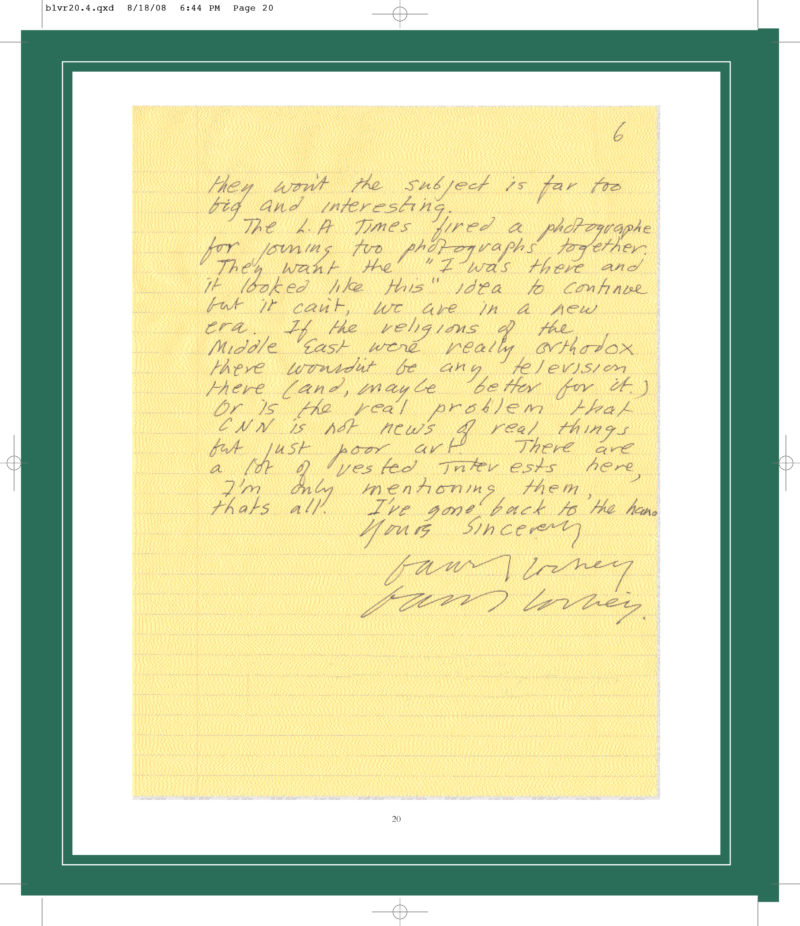

In my new capacity as director of the New York Institute for the Humanities at NYU, I decided to convene a conference on the question in December 2001, inviting art historians and critics and artists from all over the world. Passions ran high across all three days of the sessions, but, much to my surprise, the real food fight broke out among the scientists, in particular between Falco and David Stork, the chief scientist for Ricoh Innovations. And though it seemed to me that Falco got the better of the argument that day, Stork hasn’t relented. Terrierlike (or rather, maybe, like a terrier named Ahab), he has been pursuing Falco and Hockney throughout the world ever since, at conferences and in polemical articles and web postings. (And Falco, for his part, has been giving as good as he’s got, across a series of ever more recondite mathematical arguments and rebuttals.) Recently Stork and a new ally named Antonio Criminisi, a Microsoft researcher in Cambridge,England, apparently got to the New York Times, which published a fairly slashing piece on the Hockney/Falco thesis on August 26, 2004. Hockney, who’d been keeping his peace for a while, thereupon erupted with a six-page handwritten rebuttal of his own in which he tried to put the entire controversy in a broader context, which he faxed to the Times. But which they didn’t acknowledge. So, we publish it here.

Note: Those who would like to explore the backdrop to the whole controversy are invited, in addition to delving into Hockney’s Secret Knowledge volume, to surf the web in order to read the New York Times article, my own two pieces on the early stages of the theory, and both Falco’s and Stork’s websites, links to all of which can be found at http://www.believermag.com/hockney/ ✯