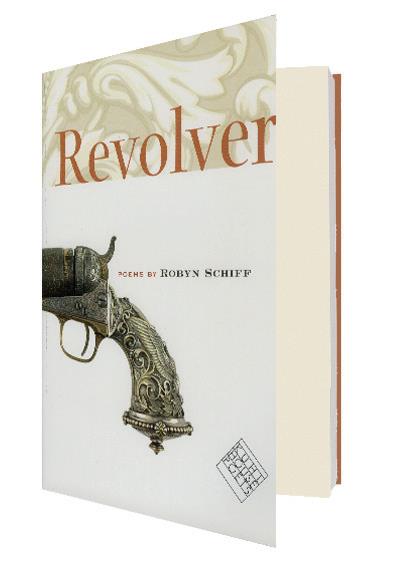

Schiff is a poet who writes about well-made things—the eponymous Colt revolver, steam ship furniture, a designer dress. Her poems are themselves well made, and uncommonly elaborate, things: they ask why, and when, we enjoy such qualities as they admire—elaboration, complication, flourishes, and virtuoso details.

All her poems describe things, but none describes just one; rather, they skate across uncommon associations. “Project Paperclip” moves from the eponymous government program (which brought Nazi rocket scientists to the U.S.) to German folk-art drinking glasses “in the shape of a / horn, a stag… a penis / or a boot,” to the legendary Chinese man who tried to visit the moon in a floating chair, to the Asian Longhorned Beetle (which hollows out wood), to The Amityville Horror, to “a silk peasant blouse that throws its purple // silk light back at the moon it came from,” first sold on or around September 11, 2001. One of the pleasures in reading the poem lies in seeing how she gets from one thing to the next—and how they all come together by the end.

Schiff carries such associations through complex sentences, often set off or cut up by syllabic (or nearly syllabic) stanzas like Marianne Moore’s, and sometimes framed by demanding forms: the reverse canzone, for example, whose fifty-seven lines (four twelve-line stanzas and one of nine lines) all begin with one of just five words taken from the pattern of words in a canzone immediately preceding it. Schiff can sound studious (like Moore) or enthused (like Albert Goldbarth), or flirtatious, or frightened, or indignant, or tongue-in-cheek, as when, in “Eighty-Blade Sportsman’s Knife, Joseph Rogers & Sons,” she explains: “It is not grace / or contempt, but repetition that sharpens / me, and as repeating your / own name contaminates it the same way / a human’s touch repels a mother bird / from her eggs, I don’t think // I want to think about me today or ever.”

As in her first book, Worth (Revolver is better), Schiff often highlights the sadly durable links between beauty and inutility, and between aesthetic value and cold cash. Another recurring subject is the way we human beings have of finding patterns everywhere, and of making patterns where there are none to find. Myths explain the inexplicable; all patterns stand finally for conjecture: “the / plaid known as gun-check consists / of infinite weaved stairways / leading up and up and up” into an artificial heaven.

Thinking constantly about the applied arts (from confectionary to arms manufacture), Schiff also asks why we have fi ne art, why we care about poets, why we have poems. “H5N1,” a poem named after avian flu, opens with an allusion to Keats: “My mask aches, and a drowsy numbness pains / my lungs.… and low, undetected / pathogenic virulence ruffles every / thrush’s plumes.” It is only a slight oversimplification to say that for Schiff, we ought to use, and to cherish, elaborate techniques (in cake-making as in poetry-writing) because we are all going to die. To cherish odd bits of the material world (even the bits that have brand names embossed) is to train ourselves for better appreciation of the even odder, smaller bits we call selves, or souls: Schiff ’s method may bring mere “grist of the material world,” but “the immaterial / grinds smaller yet.”

Format: 84 pp., paperback; Size: 8″ x 6″; Price: $16.00; Publisher: University of Iowa Press; Among the manufacturers, brands, and labels mentioned: Colt, Taylor & Sons, Hoffman-LaRoche, Glock, Porsche, Rite Aid, Woolworth; Representative lines: “Obliteration is an // opportunity. I was thinking this the other day / over cocktails at the Palmer House in downtown / Chicago; designed after the Great Fire, / the ceiling of its // barbershop was tiled with silver dollars / that flash inwardly when customers close their eyes / like the first symptoms of the kind of migraine / that makes you pull onto the shoulder // of the road and put your head down on the steering wheel.”