As an artifact of the post–World War II US baby boom, Ruth Krauss’s 1957 picture book Monkey Day makes perfect sense. It doesn’t just tell the story of a population explosion and attendant housing boom: it cheers for one. It opens on Monkey Day, with a human family bearing gifts for a girl-monkey. When one character, the girl who “loves monkeys,” presents the gift of a boy-monkey, there follows a chain of events on which schoolyard rhymes are built: a monkey marriage, a monkey baby, more monkey babies, and more monkey marriages. After the first baby monkey appears—as a tiny, solitary being—monkeys take over in disturbing numbers. In the wake of a mass monkey wedding, the primates emerge as apparently autonomous, increasingly verbal, and totally intent on building their own homes.

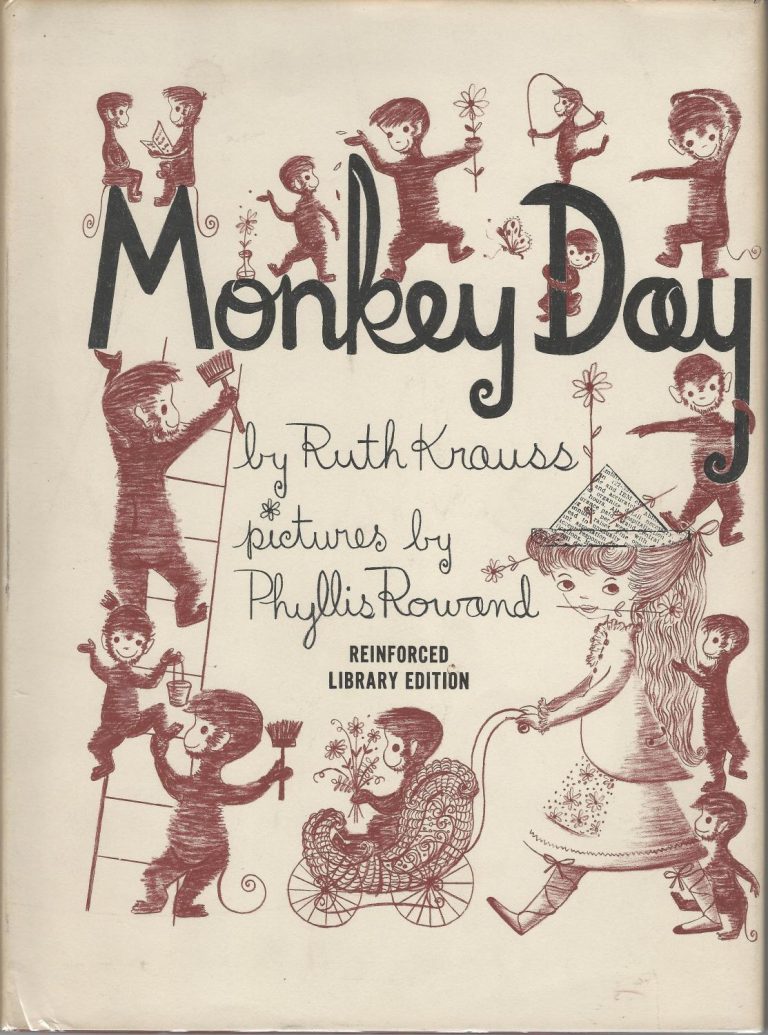

Krauss, a prolific children’s author, had already written about reproduction, or some portion of the process, in what have become her two most enduring titles: The Carrot Seed (1945, illustrated by Crockett Johnson) and A Hole Is to Dig: A First Book of First Definitions (1952, illustrated by Maurice Sendak). Both of these are simple and spare and self-contained: a single carrot is grown from seed in the former; the latter offers a concise expression of baby-making (“Cats are so you can have kittens”). Monkey Day, on the other hand, is hyper and complicated and fecund and ultimately very, very full of monkeys, and its excesses are made all the weirder by illustrator Phyllis Rowand’s crazy-grinning efforts.

As a boomer text, though, Monkey Day holds still long enough for momentary insights into what might have created the political sensibilities of the generation that grew up looking at its pages. Its portrait of a real demographic shift gives credit, or blame, to its female characters, the story’s undisputed progenitors, who sometimes operate through subterfuge. “The woman,” as Krauss calls the human mother, carries a “bundle of surprises” on the first Monkey Day, when everyone else offers unwrapped, nameable goods; the girl who loves monkeys, defined by her pro-monkey-baby agenda from the start, not only engenders monkey couplings—repeatedly, obsessively—but also performs a wedding song. Her tactics work like magic. By the end of the book, which finds her singing once again as the monkeys build their homes, she seems at least as responsible for the population explosion as do the coupling monkeys themselves.

So it’s surprising to see gender stereotypes upended here as well as preserved. “The man” knits socks and bakes...

You have reached your article limit

Sign up for a digital subscription and continue reading all new issues, plus our entire archives, for just $1.50/month.

Already a subscriber? Sign in