I’m standing in a patch of grass, looking across four lanes of traffic at a Kia dealership whose windows read CASH FOR CLUNKERS, and whose speakers play a voice droning “Sales line one, sales line one” loud enough for me to hear over the roar of the semitrucks and planes passing overhead. This patch of grass is in Eastwick, the southwesternmost neighborhood of Philadelphia, and the one next to mine. I’m the only person walking for a mile, so drivers turn and stare as I approach a telephone pole with prayer candles scattered around its base and a teddy bear tied to it with cord. It bears a piece of blue posterboard with the words LONG LIVE STRAWS WE LOVE YOU, GOD LOVED YOU MORE HE COULDN’T WAIT written in black Sharpie. There is an opening in the cluster of trees that separates where I stand from the Schuylkill River Tank Farm, where people have dumped tires, plastic bottles, and an old silver-and-black TV.

Eastwick is perhaps best known for being the Philly neighborhood that always floods (it sits between the Cobbs and Darby creeks and the Schuylkill River), and for containing part of the Philadelphia International Airport, and for this environmentally hazardous site where I now stand. The tank farm is part of the former Philadelphia Energy Solutions oil refinery, which was the biggest and oldest refinery on the East Coast and was the largest air polluter in Philadelphia until, in 2019, it exploded. Eastwick’s soil and groundwater are heavily contaminated with benzene (known to cause leukemia and lymphoma, especially in children), lead, xylene, and other toxic compounds—and still contain three times the EPA’s actionable level, even since the plant shut down.

Eastwick also once hosted two landfills—one of which overlooked a residential area—that also leaked industrial chemicals into the soil and groundwater, until they were closed and capped in the early 2000s.

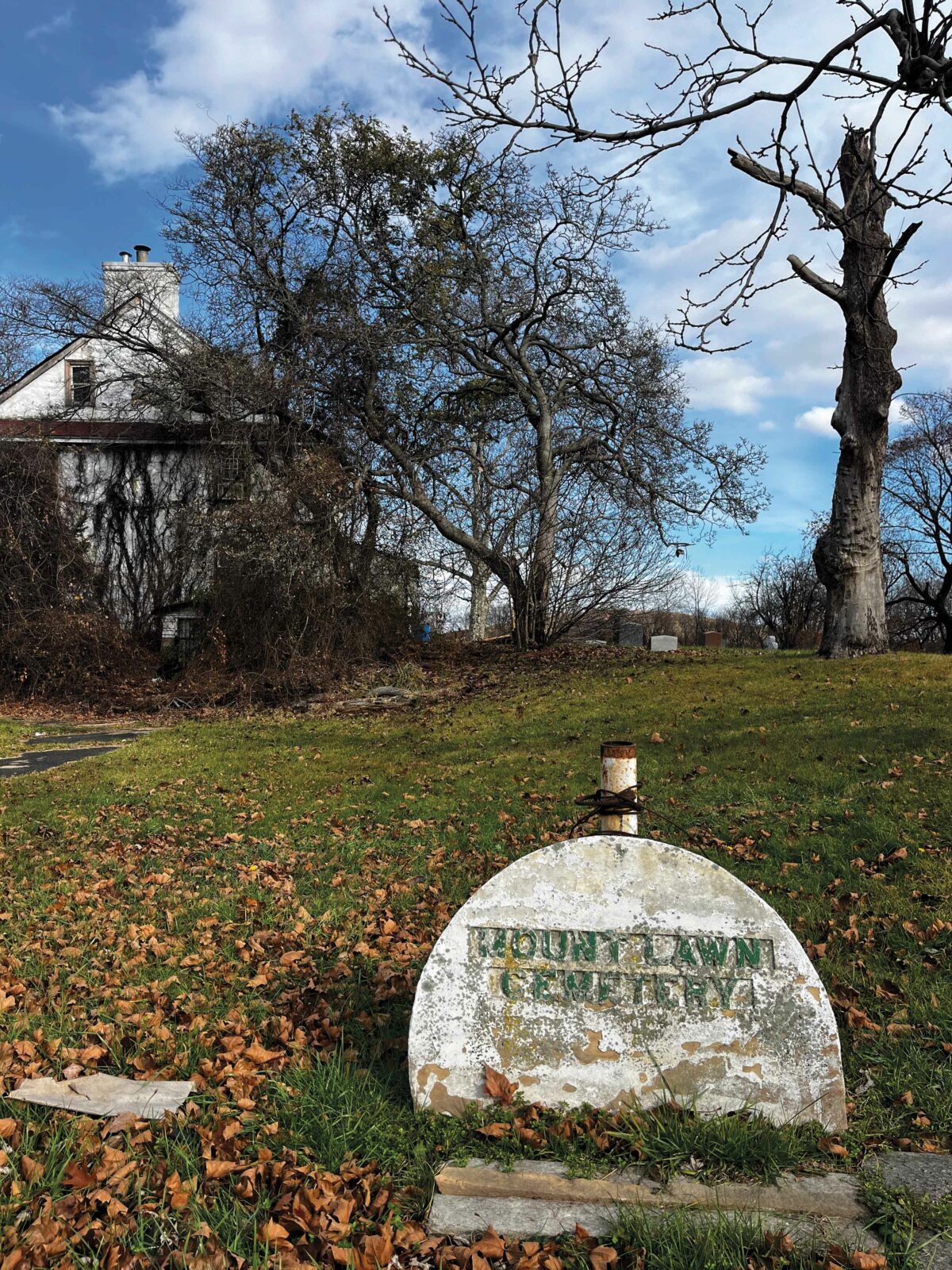

Eastwick is Park ’N Fly asphalt lots and illegal trash dumping; it is I-95 and Cargo City, a major FedEx shipping hub; and it is George Wharton Pepper Middle School, closed in 2013 due to chronic flooding, and then abandoned. In 2018 the Philadelphia Department of Streets reportedly picked up more than twenty-six tons of garbage and five thousand used tires from the school’s grounds. Eastwick, I’m seeing, is now a place where things are moved and sold, stored and forgotten. But it was not always this way.

In order for something to be sacrificed, it must first be precious. After all, in one of our most famous stories of sacrifice, it is not just anyone whom Abraham is asked to kill to prove his faith in God, but his own son. And oh, how precious Eastwick once was!

Even in the mid-twentieth century, Eastwick was 5,700 acres of freshwater tidal marsh in a semirural community, where vast open spaces attracted residents who wanted to live off the land, as well as weekend visitors from more densely populated parts of Philly. Its inhabitants included Black people, many of them descendants of formerly enslaved farmers in the South who had come north during the Great Migration; Jewish people from Eastern Europe; Italian people and Roma people. Everyone lived side by side; each family owned their own land and grew much of their own food. “A Huckleberry Finn experience,” residents say, verbatim, over and over again, in a recent oral history project. “No racial strife. Pristine land. Total freedom.”

They grew corn, greens, watermelons, grapes, apples, peaches, strawberries, blackberries, and medicinal herbs in Eastwick. They canned. They kept chickens; they fished. They wandered in the woods. They swam in the Delaware River.

Perhaps the city of Philadelphia did not yet know what it was sacrificing, or perhaps it did know but did not care. Unconnected to municipal infrastructure, Eastwick lacked sidewalks and sewers, and instead of looking precious to official eyes, perhaps it looked empty. In 1950, motivated by worry over suburban flight, and newly rich from postwar grant dollars, the city declared Eastwick a “blighted slum” and scheduled the neighborhood for “redevelopment.” The plan was to build housing complexes where the fruit trees and corn fields and woods had once been. Starting in 1957, the city used eminent domain to acquire more than two thousand homes, displacing 8,636 of the 19,300 Eastwick residents, and breaking up the shape and character of this relaxed, racially integrated community. The city literally moved earth to do this, demolishing homes and raising the elevation of low-lying Eastwick by adding eleven million cubic yards of fill dredged from the Schuylkill River.

Is anyone surprised that this plan did not create the kind of tidy, modern community the blueprints had promised? The city paved Paradise and put up poor-quality housing that, over time, became parking lots. (The fill settled strangely, causing the foundations of the new housing projects to crack and lean in and ultimately to sink; many have been left vacant, while others were purchased by the Redevelopment Authority at market value and demolished.) Or it abandoned the idea of housing altogether, turning over the land to other uses. One hundred and fifty acres of the neighborhood were allocated in 1966 to modernize the Philadelphia International Airport and to build Cargo City. Twelve hundred acres became the John Heinz National Wildlife Refuge at Tinicum.

Sewers to manage the floodwaters were never built; seven tropical storms or hurricanes between 1999 and 2021 flooded parts of Eastwick with up to five and a half feet of muddy water, a problem that is only getting worse with climate change. “Development” proceeded slowly, and eventually stalled in the 1980s due to white flight from the city, which reduced the demand for homes in the neighborhood. Eastwick is now 73 percent Black, and in 2006 it was once again declared a “blighted slum” by the Redevelopment Authority, this time while the land was still under its management. These days, the prospect of development in Eastwick is on people’s lips again, but this time residents are pushing back. No more asphalt, they say; what is needed is porous ground that can absorb water, and other long-term flooding solutions. There are multiple neighborhood advocacy associations, and meetings open to the public are often packed with residents.

From where I stand now, in 2023, on Essington Avenue, I can peer through the trees and see the squat white cylinders of the tank farm, which are connected to downtown Philadelphia by pipelines that run under the river. Eastwick is a place our city has decided is unworthy of our care, even as it has produced resources that power us all.

On my way home, I stop by the John Heinz National Wildlife Refuge at Tinicum, the only remaining piece of what Eastwick once looked like, and remember that I came here to see the total solar eclipse in 2017 (complete with those funny glasses). There are bald eagles and blue herons and egrets and swans living in the marshland, and here you can forget that the airport is just on the other side of a fence. Perhaps Eastwick was sacrificed because the loss was necessary for an idea, an impossible idea of our city’s future that never came to pass, in which Philadelphia was magically transformed into a shiny, homogenous land of power and influence. Eastwick was, is, precious, given a different way of measuring value than the one that we have chosen—it is precious precisely because it was once wild and undeveloped, and was once a place where people lived closely together and took care of one another. But for a moment, everywhere I look, that other kind of value is visible.