To arrive at Little Bloody Run, you have to come at it sideways, from the scenic road that skirts the Niagara River. My husband, Matt, and I drive from Buffalo, where we live twenty miles upstream, though it feels closer with the current at our backs. We wash up in an overflow parking lot for a fishing platform, run by the New York Power Authority. As we park, I’m talking about seasonal depression, how deep my dread has grown in the last few weeks, as the afternoons have almost disappeared—though if I’m honest, I’m not sure the season’s the problem. Matt listens as clouds rise over the water, and I want to hurry up and reach this place before snow and darkness fall on the landscape and flatten its gradations. Because the stream itself has almost entirely been buried—what’s left runs just below the surface, underground.

Even in the best light, Western New York’s industrial scars have a way of hiding. Most people have never heard of Little Bloody Run, because it was overshadowed by a famous cousin. In the ’40s and ’50s, Hooker Chemical created Love Canal, a leaking dump that would become one of the earliest toxic disasters in the US—the so-called “cradle of the Superfund.” But when Hooker ran out of room at Love Canal, they began to pile their waste here. The new dump was called Hyde Park, and it received a slurry that was even worse than what went into the ground upriver: some eighty thousand tons of chlorobenzenes, volatile organic compounds, dioxin, and mirex, an insecticide developed for fire ants. For almost three decades, Little Bloody Run served as the natural drainage for this area. The chemicals stained the sediment a reeking orange-red.

In its heyday, the run helped create an international mystery: Canadian officials wondered why so many lake trout in the Niagara border region were dying before they reached adulthood. After a fifteen-year study, biologists realized that during the years of heaviest pollution, the Western New York chemical industry had released enough dioxin to kill all the eggs the trout laid. Because of their sensitivity to pollution, lake trout are sometimes called a “sentinel species.” Their deaths were a warning that Love Canal and Hyde Park weren’t contained—the waste had traveled miles upriver, winding up in Lake Ontario.

The start of Little Bloody Run is now buried under the cap of the dump itself. I stand in the street that passes over the old streambed, peering through swaths of chain-link fence. When you live in Western New York, this is the kind of second sight you develop when you find yourself on an empty road between man-made knolls and boarded-up factories and realize this is a place where it was once a liability to have skin, lungs, a body, never mind the sweetness of the air and the warmth of the afternoon sun on your face.

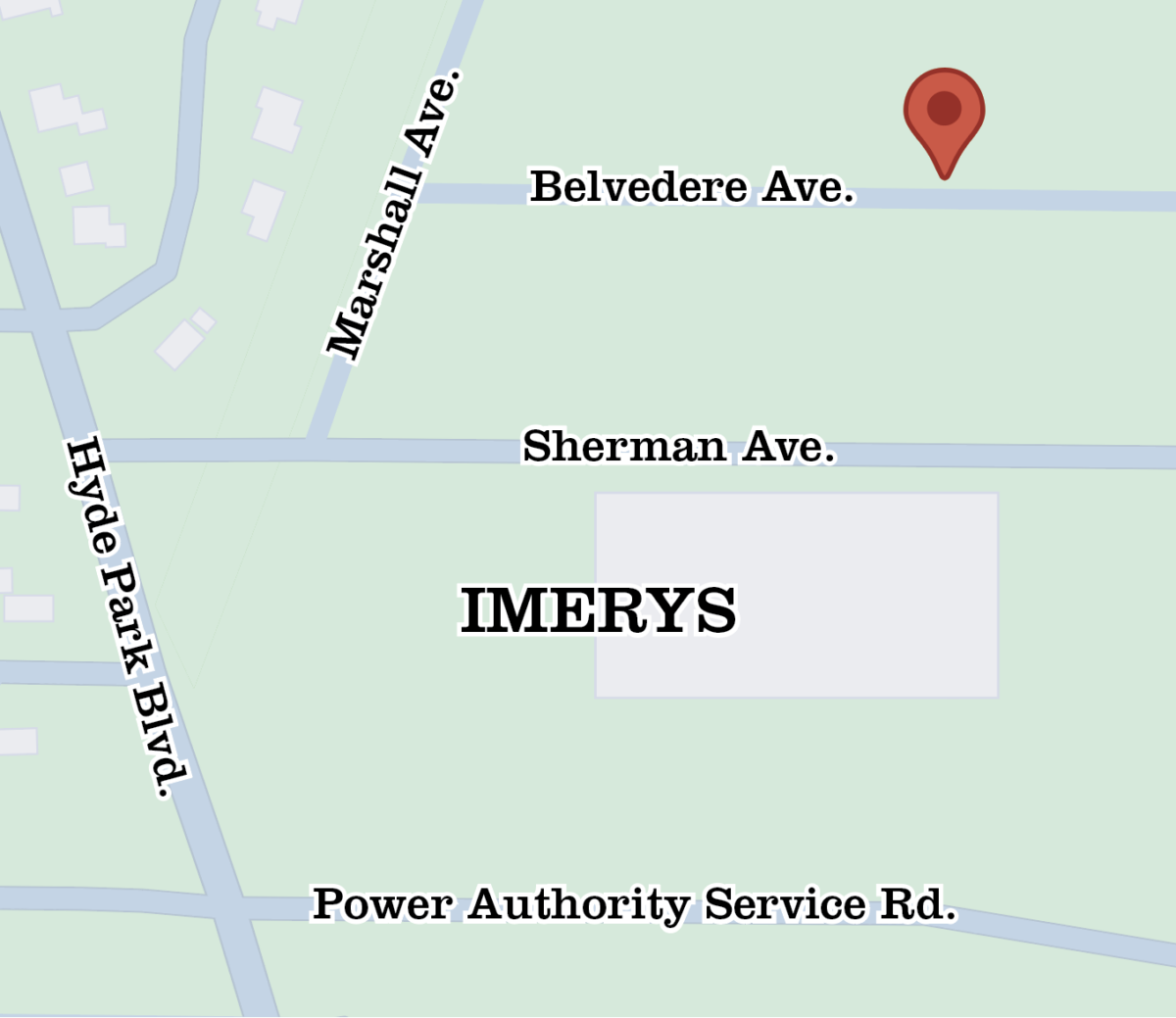

We keep walking. The swale of the invisible river makes a grassy dip under a factory that once built chemical drums, mainly for Hooker, mainly for shipping and waste. Everything gets renamed in these places where toxicity is big business—Hooker became Occidental became OxyChem—and while this factory is now owned by IMERYS, I know it was once called Greif. A trailer parked in the lot still boasts the old logo, a G with an arrow protruding from its lip. These barrels are buried all over the county—in woodlots and minor landfills, places that have never been mapped. Nearby factories sometimes paid their workers a little extra to take home a few drums and dispose of them. Which is another way of saying that “sacrifice zone” is too bordered a concept. No one fully knows, now, where all the chemicals are.

At the back of the Greif factory, oily liquid drains from a pipe, and the asphalt is greened with moss. A thick line of phragmites marches north, signaling the course of the river. In 1980, after the journalist Michael Brown helped break the story of Love Canal, he wrote about the people who lived next to Little Bloody Run, in “a cluster of about fifteen houses, set among fields of goldenrod and stands of cattails.” Some residents worked nearby, and some had been there longer than the dump, in multigenerational households, with established gardens and vegetable crops. Over the years, those who were nearest the run fell ill, suffered lesions and miscarriages, and these blocks quietly emptied—a total chemical displacement.

Not even the rivers here get to keep their names. Once, Bloody Run and Little Bloody Run were known as two distinct rills, a thousand feet apart, that both tipped into the Niagara Gorge. In 1763, Bloody Run got its name from a battle between the Seneca Nation and the English settlers, who had named a white man “Master of the Portage,” and routed wagon trains between the forts, putting Seneca porters out of their jobs moving and trading goods along the river. The Seneca fought back and won the battle. Sensational accounts say the water flowing into the gorge ran red, blood suspended in water. Nearby sites remain sacred to the Seneca Nation, Keeper of the Western Door, a member of the Haudenosaunee Confederacy, whose traditional territories extend across the whole region.

The portage trail became a paved road, and then a scenic parkway. When construction began along the river, as local author Scott Ensminger told me, it created drastic changes in hydrology that “wiped out the route of the run.” After Bloody went dry, and Little Bloody was in the process of being dredged and buried, the EPA mixed up their names in reports, conflating the two places—and the gore in the water mingled with the red of chemical slurry. The remediation of this area ultimately cost Hooker’s parent company some forty-seven million dollars. The state chipped in eleven million more. But the groundwater is still contaminated. To make money, Hooker borrowed against the long-term health of this area, but the chemicals in the ground are a debt that can never be fully repaid. In her visual essay on landfills, my friend Ariel Aberg-Riger calls this the “gutted future.”

We cross the scenic parkway and stand at the cliff’s edge. A cold wind rises from the gorge. We can see the Niagara River now, the pale teal of the rapids, the gulls massing by the hundreds, fishing the intakes of the hydropower plant. Matt goes to get the car while I hike down to the river in the last of the light, following a trail toward what was once the base of Little Bloody Run’s cascade. I’ve been told this area is off-limits now, covered with riprap, loose rock that prevents erosion and keeps people away from contaminated sediment.

On the trail I pass two men carrying reels and nets, fishers out for a day in the rapids. Little Bloody Run ends in a steep cut of rock, and I know I’ve reached the right place because it’s enveloped by chain link. That’s when I realize water is pouring out of the culverts high above me, enough that I can hear it racing under the crumbling slide of the cliff face, the stones tinged red with traces of algae or contamination, and as I step from rock to rock, I feel a liquid kind of lurching, as if I’ve lost my balance, thrown off by just how much river I have been walking over and alongside, all the way from the road outside Greif. The stream hits the open air for just a second, just as it joins the Niagara. As I watch, a golden-crowned kinglet slips under my elbow, his wings so close I can feel the wake of them in the evening air, see the trace of orange feathers sprouting from his yellow racing stripe. As babies, these birds are naked and defenseless, no bigger than bumblebees. Yet they survive. A birder once told me that kinglets like to follow people because our footsteps disturb insects in the leaf litter. And a pack of them does tail me along the edge of the contamination area, which is porous to them, their tiny beaks squalling as they dart through the overgrown fence.

This close to the border, my phone pings me “Welcome abroad.” It’s forgotten what country it’s in. I no longer believe in neat boundaries of sacrifice, or in the salve of corporate penance—that money spent proves the land is clean. I’d rather think of these fenced-off zones as the seeds of a more-than-human country built out of everything industrial recklessness has forced us to abandon. Better to believe the kinglets eat from my leaf-rustle as I turn back against the river’s course, as the night comes, as the winter sharpens their hunger. No way out but this body, climbing in the dark, buzzed by apparitions of mercy.