There is no place in Nevada’s Pahrump Valley called Yellow Pine, yet I arrive. Yellow Pine is a place invented for sacrifice. It is a new name given by NextEra Energy—a gigantic energy company from Florida worth about $175 billion—to a trapezoid of land stolen by the United States. Here, NextEra wants to build an industrial solar array on public land. Yellow Pine is located in Nevada and, preceding that place’s invention, in Newe Sogobia, unceded territory of the Western Shoshone Nation as well as the Nuwu (Southern Paiute), namely the Pahrump band of the Nuwu, themselves unrecognized by the federal government. The land is in a valley between Las Vegas and Pahrump. I grew up here.

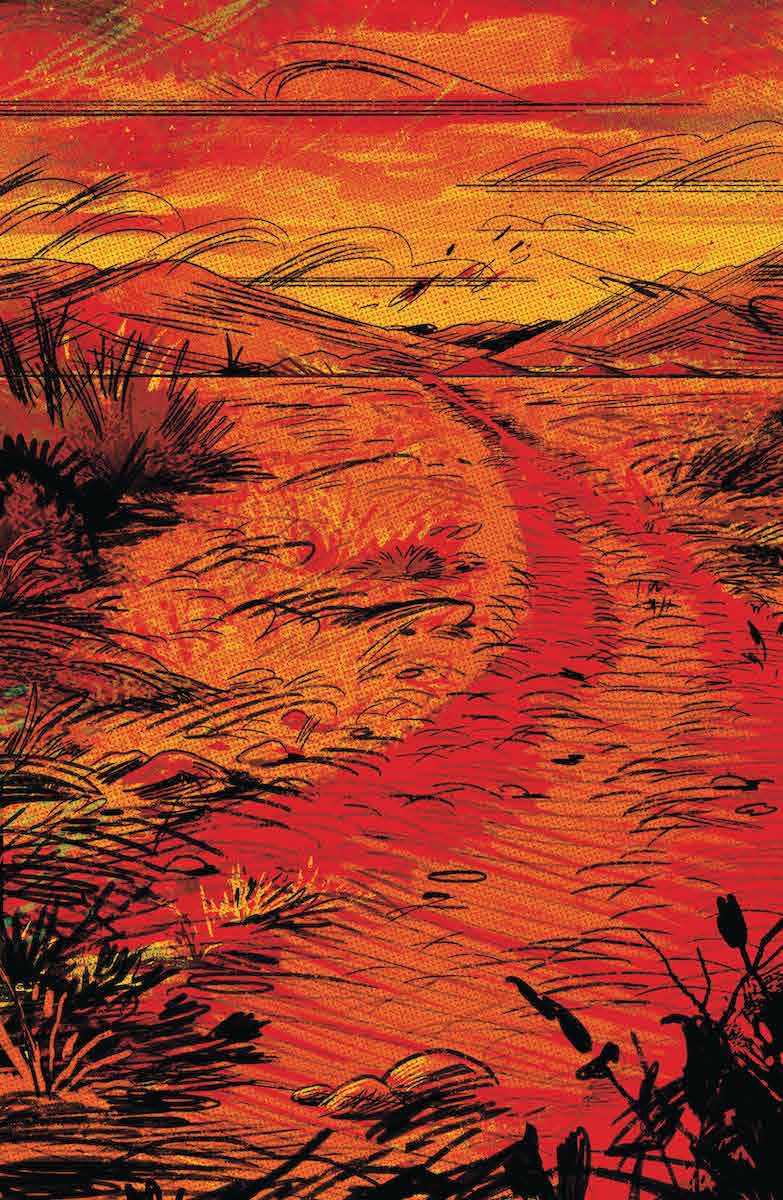

For years now I’ve come to Yellow Pine to witness the avoidable carnage occasioned by NextEra’s array-in-progress, one of a vast patchwork of industrial for-profit solar arrays in the works across 124,000 acres of the Mojave Desert and the Great Basin, a region its devotees call America’s Outback. Yellow Pine is home to about 90,000 old-growth yuccas and, until recently, 139 adult desert tortoises. It’s an undulating creosote sea that I credit for making the air I breathed throughout my girlhood. Shannon Salter, a friend who’s been living in a camper near Yellow Pine to document the desert’s destruction, calls Yellow Pine “5,000 acres of pure spirit.” It’s obviously true: from Yellow Pine one looks up to Mount Charleston, the highest peak in the Spring Mountains and a key site in the Salt Songs, the ceremonial creation myth song cycle of the Nuwu.

The adult tortoises of Yellow Pine have been relocated across the highway to a dried-up spring, making them “refugees,” as a tortoise biologist I met there put it. Tortoises are not intrepid travelers. They spend their whole lives in one small, intimately memorized patch of desert, maybe a mile square. I heard about a tortoise who’d been transplanted from another site—“mitigated,” in the banal-evil lexicon of the Bureau of Land Management—dug up from her burrow and moved out of the path of industrial order only to return in search, probably, of water. The place she scratched a certain groove in the dirt so water would gather. Or perhaps in search of her mate. Instead of home or love, the tortoise met a “tortoise exclusion fence,” a tight black grid, about two feet high. The tortoise followed the exclusion fence for five square miles, until she died. The juvenile and baby tortoises of Yellow Pine were too hard for contractors to find and relocate, so they were effectively left to die.

It seems to me the tortoise is being mitigated into extinction. About thirty of the adult tortoises relocated from Yellow Pine were promptly eaten by badgers. Even in this grimness there is wonder: I lived my whole girlhood in this valley, and I did not even know we had badgers.

Wonder has its limits. I take little solace in the poetic names of proposed industrial solar arrays that, if built, would kill a massive swath of public land from Arizona to Death Valley: Yellow Pine, Copper Rays, Sawtooth, Bonnie Clare, Chill Sun, Titus Canyon. Busted Buttes 1 and 2. Gemini, Virgo, Jackpot.

According to the Bureau of Land Management’s environmental impact statement on Yellow Pine, the industrial array will result in between zero and ten jobs and the “permanent loss or degradation of native vegetation on up to 2,000 acres.” The vegetation in question is older than we have cared to determine—yucca colonies grow for hundreds of years; creosote bushes spread rhizomatically for thousands. The plants and fungi and lichen crusts here feed every category of life, from bacteria to mammals. At Yellow Pine, a suffering, yet intact and alive, ecosystem will be pulverized by “graders, excavators, bulldozers, backhoes, cutting machines, end loaders, delivery trucks.” These machines will crush the living microbiotic crust unfurled across the land like clumps of crusty velvet and scrape off the ancient and delicate interlocking stones geologists call “desert pavement,” an intricate formation of rocks, sending up a tremendous explosion of potentially toxic “fugitive dust.” The short black tortoise exclusion fence has now been replaced by tall chain link. Once, before any fences went up, I knelt beside a geologist on a cobble of desert pavement and listened as he told how these stones were once trod upon by giant ground sloths.

Newcomers call a place like this “nothing” or “empty,” in an effort (I choose to believe) to grasp its vastness, a worshipful cry at the staggering expanse of land that is an obvious balm to city sprawl, to the long-plowed former prairies of the Midwest, the ill and raided forests of the East, the poisoned, burned, cow-chewed, bombed, and plundered ranges of the American West. Yellow Pine is public land, as fraught as that notion is on stolen land, and it is our commons, part of one of the last swaths of intact wilderness on a fabulously abused continent.

The alternatives to greed-drunk, avoidable carnage are also obvious to us watchers at Yellow Pine: free, abundant, distributed community solar in the built environment. Publicly owned panels covering parking lots, military bases, dead alfalfa fields, and golf courses that never should have been built in the first place. My activist buddies demand solar in the cities, where environmentalist politics are more palatable, rather than the “all of the above” policies that would kill this land and drive the people who live nearby into deeper alliance with climate deniers and violent fascists. We hope to reject the false choice between transitioning off fossil fuels and conserving biodiversity, which threatens to shred what remains of the American environmentalist movement. The wilderness deserves life, and we need wilderness, not only to live but to live well. I would love to see California insist on truly public utilities that put solar panels on every rooftop in the state. I dream of Nevada modeling a real, sustainable energy revolution with a holistic land ethic, rejecting wasteful supply chains, for-profit extraction, and overconsumption. I fear that instead, the southwestern states will, at the Biden administration’s urging, turn the Mojave Desert into the “Texas oilfields of the twenty-first century,” as another tortoise biologist put it.

It’s been a long and bloody couple of centuries in the American West. It’s looking to be a perilous decade, especially in cities like LA, Phoenix, Reno, and Las Vegas, where, by the end of this century, it will be too hot for asphalt. Sacrifice zones are a convenient concept, but seen from against the fence around Yellow Pine, they are plainly a figment of the imagination. Embracing optional mass death to profit the same few who got us into this mess is self-harm on a geological scale. It is a deep, grievous injury to the collective soul, and such injury can never be contained. The loss my friends and I gather to mourn at Yellow Pine cannot be cordoned off. The grim folly we watch here will be a part of all of us forever. Perhaps no region of this country knows the lie of the sacrifice zone more deeply, more intimately than the thirsty, ever-irradiated desert Southwest.