I.

In 1921, three years after the end of World War I, some of the most skilled craftsmen in England started building a dollhouse like nothing the world had ever seen before—a lavishly detailed world that could never be touched by the unstable present or the uncertain future. And secreted in the 171-volume library are short works written exclusively for the dollhouse by some of the English-speaking world’s most famous writers—works that few people have ever seen or read.

Queen Mary’s Dolls’ House was commissioned by Princess Marie Louise as a gift to her cousin Queen Mary, who would call it “the most perfect present that anyone could receive.” It was a WPA project of sorts, employing over 1,500 artists and designers, who worked under the eye of architect Sir Edwin Lutyens. Dubbed “Britain’s greatest architect,” Lutyens was also responsible for the urban planning of New Delhi. What started as a frivolous plaything became an ode to the disappearing Edwardian age, sheltered from the chaos reverberating throughout Europe. Lutyens spent years designing the dollhouse in his living room, and Queen Mary visited several times a week to see it. It was finally unveiled at Wembley for the 1924 British Empire Exhibition.

Architectural critic Sir Lawrence Weaver explained its intent in 1924, seemingly with a completely unhinged future in mind: “For the antiquary of 2123 the literary evidence of our current life will be overwhelming in bulk, staggering amidst the book stacks at the British Museum,” he wrote. “But a visit to the Queen’s Dolls’ House at Windsor Castle will clarify his confusions.”

During the seven months it was on display at Wembley, 1,617,556 visitors viewed it. According to Lucinda Lambton’s new book The Queen’s Dolls’ House, Lutyens’s exquisite creation was made “to a scale the public could relate to.” “Whereas, in a real palace they would have felt lost and overawed,” Lambton writes, “in the Dolls’ House, to their delight, they could feel safely at home.” In July 1925, it was moved to Windsor Castle, where it still sits behind glass.

The Queen’s Dolls’ house, built to the imperial scale of one inch to one foot, stands 5 feet high, and measures 102 inches north to south and 58.5 inches across. It features mother-of-pearl floors in the Queen’s bathroom, and small pillows embroidered with the letters MG and GM. When asked, Lutyens told the Queen they stood for “May George?” and “George May.” Dominating King George’s bedroom is a bed designed by Lutyens himself, with the royal arms stitched into the headboard and ostrich plumes growing like exclamation points from the corners of the four-poster. The house also has a lavish saloon, and a luggage room full of suitcases, hat boxes, and steamer trunks. A parasol identical to the Queen’s, manufactured by Briggs, leans inside a closet in the Queen’s wardrobe. A gramophone in the nursery can play the British national anthem, the bathroom is stocked with Bromo toilet tissue, and two working elevators, one for passengers and the other for baggage, are rigged with cables made of fishing line. The garage is home to six working automobiles (including a Daimler limo and a Rolls-Royce 1923 Silver Ghost), while a Rudge motorcycle with a sidecar idles next to a gas pump.

The project was an earnest tribute to the legacy of English manufacturing and preserved all the hallmarks of British royal life. Alfred Dunhill, the famous tobacconist, included tiny cigarettes, cigars, pipes, and tins of “my mixture,” tobacco custom made for the King. A cellar full of impressive wines and liquors includes two dozen bottles of Premier Cru Château Margaux 1899, each filled with just enough wine for a small taste on the tongue.

But dolls never splayed their porcelain arms and legs over the lip of the silver bathtub made for the baby Prince of Wales. They never used the kitchen with its custom cooking implements or slipped under the silk damask royal sheets in the bedroom. Only the probing fingers of the Queen tapped through the house, over the marble, up the stairs, arranging and rearranging the furniture an infinite number of times. But she would never be able to run a turquoise-backed brush through the slip of a doll’s hair while sitting her down in front of her diamond-encrusted mirror and vanity. She would never pack a childlike doll into one of the wool-lined gauze pneumonia jackets, carefully laid out in the children’s rooms.

The designers and artists involved with the building of the Dolls’ House, along with scholars and historians, or “The Committee of the A.B.C.D.E.F.G.H.I.J.K.L.M.N.O.P. of the Queen’s Royal Dolls’ House—the committee of Architects, Builders, Carpenters, Drain-inspectors, Electricians, Furniture-makers, Goldsmiths, Haberdashers, Image-makers, Joiners, Kipper-cutters, Librarians, Muffinmen, Numismatists, Opticians and Plumbers,” according to novelist A. C. Benson—made their first order of business never to allow a doll to enter the perfected rooms of the Dolls’ House. Benson explained the committee’s reasoning in The Book of The Queen’s Dolls’ House:

A Doll is not a human being in miniature at all, it never produced the slightest illusion of being a real person made magically small and anyone can easily imagine what a monstrous deformity a Doll would be if it was magically restored to human size…. You can look at the pictures, and see what they are meant for, you can read the books, and understand more or less, what they are about…. But Dolls could have done none of those things, they might have fixed their glassy eyes on the pictures but they would never have seen them… and if they had ever got into bed at all, they would probably have been placed there with all their clothes on, because of their revolting appearance when undressed…. Dolls, in fact, in the Dolls’ House would have been the most gross of solecisms.

II.

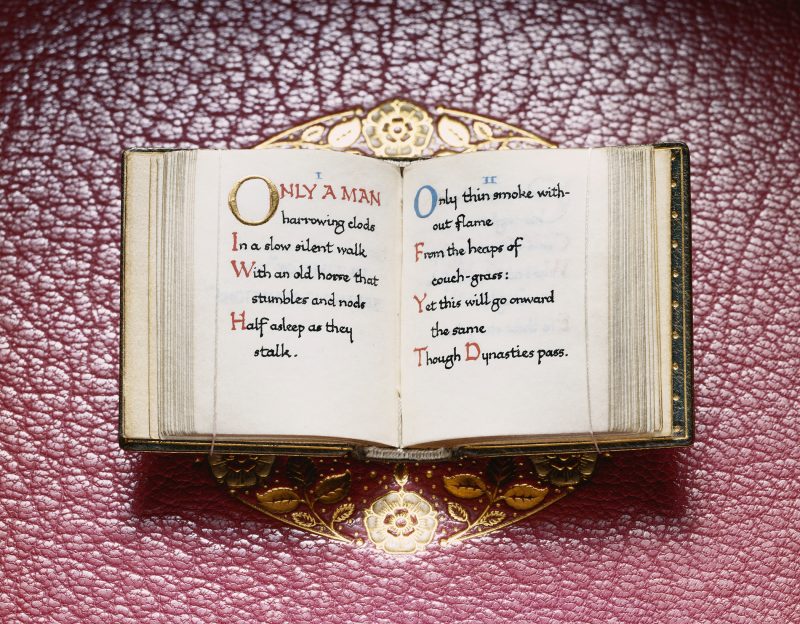

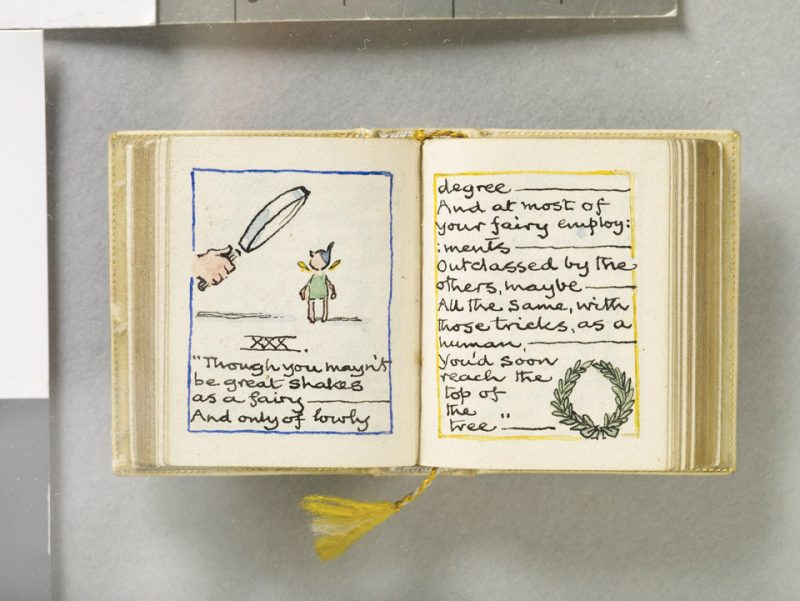

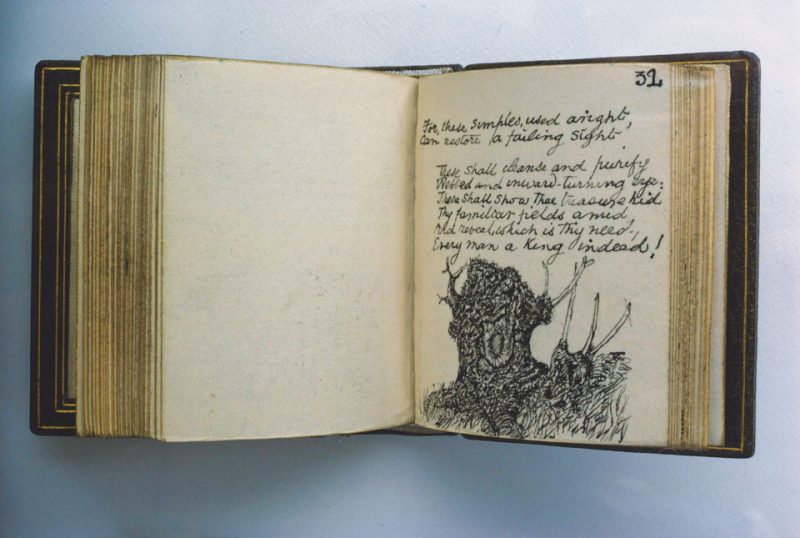

The library is a breathtaking showcase of miniatures, a Borgesian world ensconced in rich walnut. Alongside the usual suspects (Shakespeare, Dickens, the Bible) are original works by the most prominent authors of the time. Each leather-bound volume is the size of a postage stamp, and a typical page holds but a single paragraph, sometimes accompanied by a petite illustration drawn by the author.

Princess Marie Louise, the dollhouse’s self-appointed librarian, asked hundreds of writers and artists to submit original miniature works for the library, a remarkably varied list that includes J. M. Barrie, Joseph Conrad, Aldous Huxley, W. B. Yeats, G. K. Chesterton, Robert Graves, Thomas Hardy, Max Beerbohm, A. A. Milne, landscape painter Paul Nash, and F. Gregory Brown, famous for his posters of the London Underground. And they did, in droves, often submitting their miniature manuscripts within days. One hundred and seventy-one writers and seven hundred artists participated. (Virginia Woolf and George Bernard Shaw were among those who declined; T. S. Eliot wasn’t even asked.) In a way, the Queen’s Dolls’ House library is the most comprehensive, genre-crossing anthology of the era’s prominent writers, their entries unified by a specially designed bookplate created by Ernest Shepard, illustrator of Winnie-the-Pooh.

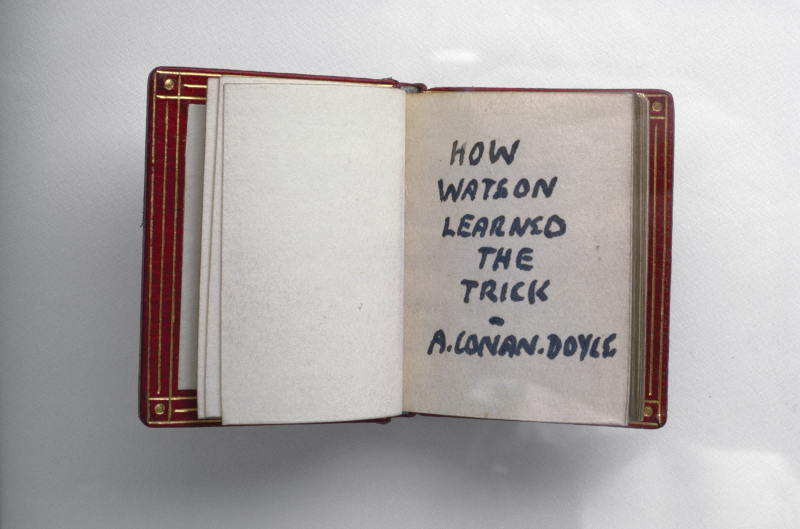

Rudyard Kipling filled his mini-book with absurd verses like “Eddi’s Service,” in which a priest delivers a sermon to a bullock and a donkey, the only members of his congregation. A. E. Housman selected “the twelve shortest and simplest and least likely to fatigue the attention of the dolls or the illustrious House of Hanover.” Sir Arthur Conan Doyle included a story called “How Watson Learned the Trick,” in which the good doctor deconstructs Holmes’s “superficial trick” of logical deduction, and provides a general study of Holmes himself, a depressed case who has nothing going for him as of late. “I was thinking how superficial are those tricks of yours,” Watson muses to Holmes, “and how wonderful it is that the public should continue to show interest in them.”

With the princess and her library collaborator, author E. V. Lucas, requesting literature only a doll would be interested in, it’s likely some writers felt constrained. Would dolls be interested in books written in Latin? Lucas thought so, and implored some writers to compose tiny Latin tomes for the library. No request was too peculiar for the Lilliputian library. Lucas relates that Lutyens asked the orientalist Sir Denison Ross “if there were any dolls in the East,” proposing, “as a suggestion… rather than direction… that if so, might not the English dolls like to hear about this?”

Medical works can also be found, such as those by Sir John Bland-Sutton, a preeminent surgeon of his day. According to Lambton, “Bland-Sutton wrote that his little monograph on doll surgery would be a source of amusement and pleasure… with such recommendations as what to do when a doll’s eye is damaged: ‘The roof of the skull is cut off with a sharp knife, as the head of a doll does not possess a brain.’” Other surgeries for doll health were laid out, complete with diagrams.

Not all the writers created books worth reading. In Edith Wharton’s Elves’ Library, she wants to register her delight in being involved with the library, but doesn’t have much to add:

The Elfin Mother, scanning

Her Times at set of Sun,

Learnt of the Dolls’ House

planning

To solve the Housing Problem,

And honour the Good Queen,

And quick thought she: —“My Libraree

Must with the rest be seen!”

Wharton described her poem as “a doggerel… unworthy of so charming a destination.” Ethel M. Dell was even lazier, copying and pasting passages from her three best-selling romance novels, The Knave of Diamonds, Bars of Iron, and The Hundredth Chance.

One of the most fascinating volumes in the Queen’s Dolls’ House is A. B. Walkley’s Histrionics for Dolls—A Letter to a Debutante. Walkley, a well-respected British drama critic and the inspiration for Shaw’s Man and Superman, wrote a cautionary letter to a young starlet doll. “So, dolly dear, you want to go on stage!” he begins innocently enough. “That does not surprise me, in a young person of your charming sex.” The doll in question has red-patched cheeks, a wire-bound body, and an unmovable mouth, but when squeezed in the right places she can utter, “Mam-ma.”

For Walkley, the doll’s “gravest disability” is never being able to close a hand or make a fist. He goes on to list the parts she will never be able to play: Ophelia, who has to distribute flowers; Lady Macbeth, who calls for daggers to hold; Desdemona, who drops her handkerchief. This actress, ruminates the theater critic, will have her acting career stunted by her handicap. Dolls are not in control of their movements or elocution; all of it is manipulated by “the gentlemen who looks after the wires.” His vision of these actresses, with their barely moving parts, calls to mind Hans Bellmer’s haunting sexualization of dolls in the violently jumbled La Poupée.

These books weren’t the only subversive element in the library. The library was the only place in the Queen’s Dolls’ House where World War I was remotely acknowledged. John Buchan contributed the Battle of the Somme, an account of the French and British offensive against the Germans that marked the end of trench fighting in World War I, writing: “On the Somme fell the flower of our race, the straightest of limb.” War poet Edmund Blunden wrote about his obsession with the war, in verse, while correspondent Sir Philip Gibbs’s The Unknown Warrior described the anonymity of battle.

Writers let the darkness seep into this manicured house. Visions of limbs, hands, and disjointed bodies show traces of a war lacquered over in other parts of the house by frescoes and painstaking murals and fine drapery. These authors allowed the horror to sneak in, buried it in leather-bound miniature—a challenge to the obsessive attempt to memorialize a perfect, unspoiled past.