Seasons change, silence remains

Almost a century ago, artists told stories of proletarian struggle in “wordless novels,” woodcut sequences heavy on allegory and moral triumph in the face of oppression so powerful it literally silenced the characters. The open forges and armed goons of the Industrial Age are history, but not the crushing oppression that robs the every day worker—or consumer, as she is now labeled—of anything to say. Today, that oppression takes shape in routine, with advertisements and logos as its propaganda organs.

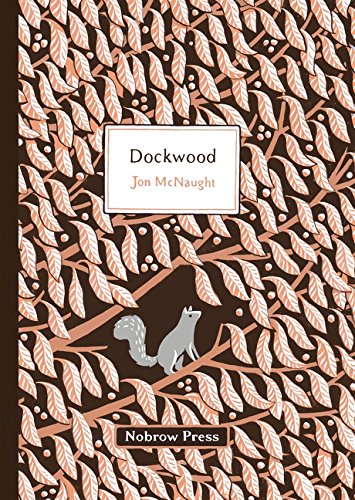

During a single October day in the titular town of Jon McNaught’s Dockwood, a cook goes to work at Elmview Nursing Home and a paperboy delivers the day’s late edition. These two characters are related not by causality-driven plot but by the coincidence of a shared commercial landscape, including a giant billboard that appears early on when a man papers over an ad for a “summer sale” at Topshop with an ad for “autumn bargains” at Matalan. Seasons change, silence remains, and synonyms serve their purpose, muting communication through repetition. The process erases difference and leaves passersby—an audience by chance, not choice— with a simple ready-made message: consume.

McNaught’s characters speak little; their world is muted and flattened, like the advertisements around them, into a single plane on which nothing is louder than anything else. But because this is a story told in comics, such silence is untenable. As soon as the reader finds the iconically simplified imagery inherent in the form, there is meaning—which is to say noise. So we find worry in the cook’s two slanted eyebrows, and adolescent ennui in the frequently eyeless face of the newspaper boy. The characters speak, if not to each other then to the reader (however hokey that may sound).

As in most comic books, part of Dockwood’s narrative comes from this familiar habit of filling in the familiar: the act of making meaning by recognizing and elaborating upon icons becomes part of the narrative. Just as we follow Superman as he saves the world again and again, both ignoring and trusting the inevitability of what we know will happen (i.e., that he saves the world), here, too, we allow patterns, and variations on patterns, to pull us along. Without these, the narrative fizzles; the comic goes silent. This is exactly what happens with the advertisements in Dockwood the town: they’ve blended so well into their real-world context that viewers stop seeing the variations that create meaning. Silence takes over.

Not so in Dockwood the book. Ironically, or perhaps just cleverly, silence threatens to take over in the overall story because patterns—and thus progress—are hard to come by therein. But both are there, thanks to the limiting framework of the comic: they are there beneath the world’s quiet, quotidian predictability, in the muted pink and blue sky, and in the act of comics-reading itself, during which the reader can’t help but fill in the missing imagery with details drawn from her understanding of her own landscape. Try reading a comic without turning symbols into fuller images: you can’t. We see ourselves everywhere.

We see ourselves especially in the comfort of routine, how it creates the illusion of time stilled, of nothing happening. Even though time passes, routine shields us from noticing: if we’re doing the same thing we do every day, it might as well be yesterday or tomorrow. This inertia is abetted by a physical world dominated by consumer objects that are identical everywhere for everyone—those billboards in one of Dockwood’s opening panels, for instance. We see ourselves in these objects, too, objects easily replaced by new ones that feel exactly the same, no matter the season.

This isn’t necessarily troubling, until it seeps into the way we think about people—until they become objects, silent and infinitely replaceable, free of the burdens of emotional context and the passage of time. Hence the rack of magazines at the newsstand, whose covers bear the classics of objectification (women, cars). Hence the way we recognize brands in partially elided logos—a candy wrapper’s SNIC, a video-game console’s AYSTATION 3 —in the same way we recognize worry in slanted eyebrows. We get used to the silence of objects; we get used to not talking to them. So why would we talk to the face with the eyebrows? If everything is the same, day after day, what is left to say?

Still, time passes. People talk, albeit rarely in Dockwood. Consumerism hasn’t deadened us to the passage of time—it’s just given us something else to focus on. We see as much when the protagonist of the nursing-home story learns that “Mrs. Madson died last night.” He doesn’t recognize the name until his coworker clarifies—“Room 12”— to which he finally responds,“I liked room 12.” Only when he visits room 12, its floor covered in the kind of Las Vegas–style carpet that hides stains in blindingly repetitive patterns, does the person become distinct from the room. There the protagonist finds the remnants of life—a mirror, dead flies on the windowsill, Kleenex—pieces that rattle and rustle and break the silence by bearing, in their specificity, the trace of the person who touched them.

Despite a few such minor interruptions, cycles dominate Dockwood. Even some of the smaller narratives within it are cyclical: a BBC nature show about autumn, a video game played by a teen in the second story. Both telegraph inevitability: the first in a tedious discussion of seasons, so unremarkable because of their inescapability; the second in the parameters of limited plot and a false sense of agency.

The video game, though, gives us hope, even if it’s a distressingly modern kind. Controller in hand, the second story’s protagonist learns how to find agency in a limited framework. Like the town’s inevitable rhythm, the on-screen narrative, so hemmed in by structure, demands to be filled in. And like that narrative, Dockwood waits for the reader to fill it in with the narrative of narrative. We always come up with a story, even when silence envelops us.

Rachel Z. Arndt

A good deaf man is hard to find

In recent months, deaf actors have launched a series of online protests to draw attention to ableist discrimination by Hollywood production teams. They lack opportunity not because deaf characters don’t exist, but because producers refuse to use actual deaf people to play them. In response to objections to his decision to cast a hearing actor as a deaf lead character in the film Avenged, filmmaker Michael Ojeda explained that “it really wouldn’t have been logical to have a deaf girl playing the role because it was so action-intensive; she would have got hurt.” Since then, the deaf community has set its sights on Stephen King’s The Stand, a mammoth apocalyptic novel and Warner Bros. franchise now slated to become an eight-part Showtime miniseries and a feature film. It is uncertain whether a deaf actor will be cast, or even invited to audition, for the role of the twenty-two-year-old “deaf-mute drifter” Nick Andros.

The literary world has also had its share of diversity scandals, and perhaps, given the low number of deaf and hard-of-hearing authors writing in English, it is unsurprising that a good deaf man is hard to find in fiction. This is not to say there aren’t any deaf people in books, just that they are rarely well-rendered humans complex enough to transcend being used as symbols. But Andros might be the closest thing fiction has to a successful deaf character.

Despite a difficult childhood that includes not only being born deaf but also the premature death of his mother and subsequent time spent in an orphanage, Andros has managed to learn to read, write, and read lips perfectly. Even the characters around him notice that he is smart; in their first meeting, Sheriff Baker concludes that “Nick Andros must have some pretty good equipment upstairs.” The ease with which Andros communicates is a stretch: in reality only 30 to 60 percent of speech is visible on the lips, and Andros can even lip-read people on television—a task approaching impossibility, in my experience. But he is intelligent and resourceful from the outset of the novel, an exciting start.

We are introduced to Andros while he is being badly beaten at an Arkansas bar. King makes a point of noting, in his narration and via other characters, that Andros cannot scream. “Why don’t he yell out?” one of the bullies asks repeatedly, disturbed by Andros’s silence even while beating him bloody. While deaf people can be nonverbal or “mute” to varying degrees without extensive speech therapy—and it makes sense for Andros, given his rough childhood—we certainly can make noise: we are, in fact, notoriously loud, lacking the desire to self-censor our noise output. Only later is it revealed that Andros’s deafness is a birth defect and that he was also born without vocal cords—which, though fair enough, is misleading, since these defects are neither commonly paired nor what the term deaf-mute traditionally describes.

Andros’s world as King defines it is often couched in the negative: a description of ambient sound followed by something like “but he did not hear this” is a frequent construction. At one point Andros, “in [his] silent movie world,” watches the sheriff “explode several sneezes into his handkerchief.” About halfway through the novel, Andros has a sudden and desperate desire to hear and understand music; he is described as having “never been happier” after he dreams that he can hear and speak. Certainly deafness in a hearing world can be frustrating, but it’s unlikely that a person as bright and capable as Nick Andros would tie his self-worth so tightly to the ability to hear a guitar.

This is the plight of the average deaf character: to be plagued by the hearing author’s own discomfort with the idea of silence. In Carson McCullers’s The Heart Is a Lonely Hunter, for instance, John Singer is a silent sufferer whom hearing people use as a sounding board and mourn only vaguely after he kills himself. One need not look past the cover copy of Joanne Greenberg’s In This Sign to find the deaf couple therein labeled “inexperienced, ignorant and bewildered” in their struggle to “survive in the silent world of the deaf.” A pull quote attributed to the New York Times calls the book “a miracle of empathy,” as if imagining deaf people as humans with families required magical powers.

Still, where other writers stumble, King shines by making Andros a fleshed-out character who has thoughts, and not only thoughts explicitly tied to his deafness. As The Stand progresses, it’s clear that Andros possesses a natural leadership quality: other characters look to him for direction, and he becomes head of the Free Zone Committee, the group formed in opposition to supervillain Randall Flagg’s sphere of influence. Via gesture and writing, Andros proves himself an effective communicator, and his deafness does not cut him off from others. Better yet, he has a sense of humor and a strong moral compass; he gets hungry and tired; he has sex. In his first encounter with the bubbly Julie Lawry, there’s a disarming charm to his boyishness, even while Lawry condescends to him:

“My name’s Julie… What’s yours?” She giggled a little. “You can’t tell me, can you? Poor you.” She leaned a little closer, and her breasts brushed him. He began to feel very warm… He broke away from her, took the pad from his pocket and began to write. A line or so into his message she leaned over his shoulder to see what he was writing. No bra. Jesus… His writing became a little uneven.

That Andros ignores Lawry’s ableist drivel and has sex with her anyway makes him read not like a symbol, nor even like noble deaf character, but like any young man in a heated moment. Similarly, when the sheriff pulls out a line of classic victim-blaming—the bar in which Andros got beat up is “no place for a kid like you”—Andros refuses to bend: “Nick shook his head indignantly. ‘I’m twenty-two,’ he wrote. ‘I can have a couple of beers without getting beaten up and robbed for them, can’t I?’”

The passage is simple, but simple is the point—Andros himself doesn’t obsessively think about or discuss his own deafness, because there’s more to him than that. The novel benefits from these moments when readers aren’t made to suffer the corniness of a “silent movie world”: it’s where Andros is a person first and deaf second that the real work of character development and plot is accomplished. Perhaps the truest way to capture silence is not to mention it at all.

Sara Nović

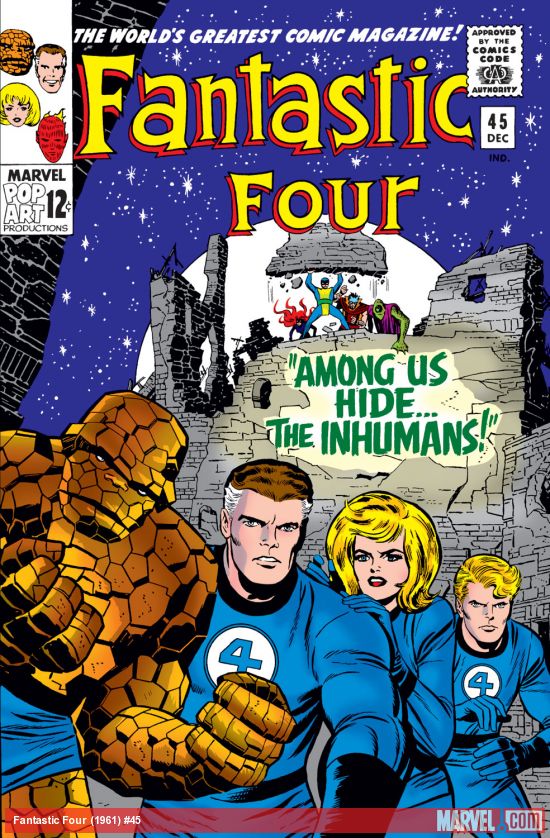

Power, without speech balloons

Stan Lee and Jack Kirby, who cocreated much of the Marvel Comics lineup in the 1960s, introduced Black Bolt in Fantastic Four no. 45 (1965): the stern, melancholy hereditary king of a hidden race called the Inhumans has a voice so powerful that he can never use it to communicate. His rarely wielded whisper is a military-grade weapon; a shout can wreck cities or knock spaceships out of the sky. His subjects sometimes comprehend him intuitively; he “can make his wishes perfectly understood,” at least to other Inhumans, and to his flying, teleporting giant bulldog, Lockjaw. When that’s not enough, Black Bolt nods, frowns, moves his eyes melodramatically, or—especially in the Lee-Kirby comics—adopts unlikely “meaningful” poses, somewhere between American Sign Language, honeybee signaling moves, and interpretive dance.

Black Bolt’s costume—one of Kirby’s snazziest—comprises a blue-black bodysuit with double zigzags down the chest, a mask with a silver tuning fork–like object on his forehead (it catches electrons), and wings that fold out like a paper fan under his arms. Gene Simmons of Kiss has said that Black Bolt inspired his signature outfit. (Some people wish Simmons, too, could be seen and not heard.)

Besides looking awesome, though, the character looks like a mordant comment on how mainstream comics get made—especially how they got made in the mid-1960s, when Lee began to identify his own name with the Marvel brand’s success. In the oft-used “Marvel method,” a writer and primary artist come up with a plot together, the artist draws most of the comic, and then the writer goes back to add the words. This process made for exciting synergy, as between Lee and Kirby, or (years later) Chris Claremont and John Byrne; it also lets writers revise what artists had made, dropping in speeches that altered the characters’ motives or otherwise reinterpreting the plot.

As Sean Howe’s recent history, Marvel Comics: The Untold Story, confirms, Lee had the upper hand over Kirby, and over all the artists, through this method and through the contracts under which they worked. Kirby, justly nicknamed the King of Comics, died in 1994, long estranged from Lee, not wealthy, and without his Marvel characters’ rights. Lee became, well, Stan Lee: he got what he wanted through his way with words—those in the speech balloons, and those in Marvel’s terms of employment. Because he says nothing, and because he looks so cool, Black Bolt can thus be read as the revenge of pencil and brush over pen and typewriter: for once, here was a character—a king—over whom the King had the last say. Stan Lee could never put words in his mouth.

Black Bolt’s silence can also stand for charisma, for monarchical remove: in the 1960s comics and some later versions, he lacks not only speech balloons but thought balloons as well— we cannot know what he is thinking. If you’re a fan of Michel Foucault, you could even make Black Bolt represent power itself, which doesn’t “want” anything, not in the way that individual people want things, but controls society anyway without ever having to speak up for itself.

More often Black Bolt’s silence represents effortful and continual self-control, or even Freudian repression. Black Bolt’s first scream saves his people by downing a hostile spaceship, but the crash kills his mother and father, then king and queen of the Inhumans. “Ever since the death of your parents, the death you believe you caused, you’ve been so bottled up, you’ve got to at least act, before you explode!” one character advises him in Annie Nocenti and Brett Blevins’s The Inhumans: By Right of Birth. (With luck, Nocenti’s trippy script will be the basis for the Inhumans movie, now slated for 2018.) “He was born guilty! and now he’s a martyr!” another character explains. “He’s dwarfed by his own silence.” Those truths or suspicions that are so powerful that kids may think but never say them—“I’m gay,” for example, or “Mom and Dad ought to split up”—find appropriate representation in the power that Black Bolt can—almost—never use.

Black Bolt’s self-enforced silence sticks in the mind not just because he’s an anomaly within superhero comics, with their usual plethora of speech balloons, but also because he’s a monarch, and a patriarch. There’s a long, dishonorable tradition—see the medieval querelle des femmes—of arguing that women talk too much, that children should cultivate silent obedience. But Black Bolt is never feminine, never childish, nor does he take orders from anyone. He’s a model of self-denial, a leader with courage, a symbol for power that does not corrupt—but also a father figure who never has to raise his voice to get what he wants. As such he illustrates another principle, a political one: silence is an expression of power only when other people are ready to listen, and when they believe you have the right to speak.

Stephanie Burt

Palpable and mute

I’m not sure why I was asked to write about Pedro Zarraluki’s The History of Silence, although I guess being a poet makes me some kind of expert on silence. It has always seemed to me that there is something primitive about the poet’s relationship to silence. We enter into it cautiously, with a kind of ceremony; we keep it around us, with equal measures of love, awe, and terror. As for all writers, silence can be our enemy, staring at us via the blankness of the page or screen. Unlike other writers, though, when we write as poets, silence stays close to our poems, protecting them in the leap between the title and the first line, at the ends of the lines we break too soon, leaving whatever absence we instinctively deem correct in its measure. Prose writers would fill that space, but not us.

The History of Silence, translated from the Spanish by Nick Caistor and Lorenza García, begins with these two sentences: “This is the story of how a book that should have been called The History of Silence never came to be written. Although common, failure is not easy to explain.” The narrator sounds more than a bit like a poet here. Because of its close relationship to silence, negation is one of the great engines of poetry. Keats, who came up with the concept of negative capability—the closest thing to a statement of purpose most poets can agree upon—addresses his Grecian urn this way at the beginning of his ode:

Thou still unravish’d bride of quietness,

Thou foster-child of silence and

slow time,

Sylvan historian, who canst thus express

A flowery tale more sweetly than our

rhyme:

The urn is married to quietness, though the two have not yet consummated their relationship. It’s also an orphan, adopted by a couple I would love to vacation with: silence and slow time. Surrounded by silence, and of course literally unable to speak, the vessel is particularly and paradoxically suited, at least in poetic terms, to tell us a “flowery tale.” (Which is a good pun, because the urn has flowers all over it. Nice job, Keats!)

I realize I am talking about Keats, which I like to do, and not about The History of Silence. If I had wanted to be clever, I suppose I could have begun with this sentence: “This is the story of how a review of a book that should have been called The History of Silence never came to be written.”

But I’m not that kind of guy, so here’s a bit about the novel: it’s about a group of friends who live in Spain. The narrator and his girlfriend, Irene, are the sort of thinky couple we might all recognize, or even be; they are not, in other words, silence and slow time. They and their friends seem to only vaguely have jobs. They throw dinner parties and know each other very intimately. There is a growing tension among them, which eventually explodes. The plot has the quality of a Shakespearean farce, in a good way.

One of the pleasures or annoyances of The History of Silence, depending on the kind of reader you are, is that it periodically becomes philosophical on the nature of silence. On the plot level, this is because the narrator and his girlfriend are continually discussing the subject, with each other and with their friends, in the ostensible pursuit of eventually writing a book called The History of Silence. Of course, they do not write this book in the end, but of course it is also being written as we read the novel, so we get a partial version of it all the same, through conversations such as this one:

“How is your book on silence going?” she asked, addressing only Irene.“I found what could be an interesting fact in the children’s encyclopedia. Female cicadas’ ears are located almost at the tips of their front legs. Strange place to have them, don’t you think? So, when the male cicada lets out his mating call— because he won’t deign to go to them, of course—the females do this with their legs (Olga spread her fingers on the table and moved her elbows from one side to the other) to find out where the lazy good-for-nothing is who wants some company. If it were me, I would never go looking for him, I’d stay right where I was gazing at the stars.”

Archibald MacLeish famously wrote,“A poem should be palpable and mute / As a globed fruit.” It must somehow use words but also be silent, because language already inevitably pulls us into the realm of untruth.

Obviously, this is a paradox.

So how are we supposed to write poetry, or speak at all, for that matter, without lying and wrecking everything? Good question. The History of Silence is ultimately about the impossibility of speaking about feelings, as well as the insufficiency of retreating into silence. This language conundrum is the true source of the emotional paralysis of the narrator, and of the departure of Irene, which, unsurprisingly, ruins his life. The narrator settles on a desperate, grand gesture involving a Polaroid camera and a trip to Managua; in the end, he writes, “The solution lay in an image, which might be rather irksome for a writer. But I have never been all that passionate about my profession.” In a way I will not describe, he becomes palpable and mute. And thus the novel ends and his new life, in the silence after it is over, begins.

Matthew Zapruder

The silence of the ducks

I didn’t get too far into Matthew B. Crawford’s The World Beyond Your Head: On Becoming an Individual in an Age of Distraction before the following passage captured my imagination:

There are some resources that we hold in common, such as the air we breathe and the water we drink. We take them for granted, but their widespread availability makes everything else we do possible. I think the absence of noise is a resource of just this sort. More precisely, the valuable thing that we take for granted is the condition of not being addressed. Just as clean air makes respiration possible, silence, in this broader sense, is what makes it possible to think.

Silence isn’t just quiet, he’s saying: it’s absence. It’s the absence of noise, the absence of stimuli. It is a thing, both aural and visual, that allows us to keep our attention where we want. And so noise isn’t just sound; it’s anything grabbing at our attention that we don’t accept or invite.

I like this idea of noise, because of course when we seek silence we aren’t really seeking the absence of sound. We aren’t all blinking at each other from inside the anechoic chamber at Orfield Laboratories in Minnesota, which holds the distinction of being the quietest place on earth, a place so quiet it sometimes induces hallucinations. I suspect that when we seek silence we are really looking for places that have the smallest amount of human noise.

I know a guy who, after hiking the Appalachian Trail, came home and unplugged his refrigerator because the hum was so loud he could concentrate on nothing else. But I’m guessing he didn’t mind the birds or the sound of trees swaying. I feel disappointed, in seemingly remote places, once I realize I can still hear cars whine on some distant road. But I’m thrilled to share a dark evening with a pack of yipping coyotes. What disappoints me about the sound of cars is that it comes from the human world. What excites me about the coyotes—in part—is that they’re not talking to me.

It must be primal. We don’t usually feel distracted when we hear birds, aside from the squawkiest squawkers; they are communicating with a world that exists without us. We can ignore it. But when humanity is announced—through a baby crying, a car alarm, a cat call, a neighbor’s fight or fuck heard through the wall—we are asked to pay attention. Or, rather, we can’t not listen. It’s not personal, but because we’re human it’s meant for us. The problem is it doesn’t tell us anything new.

Recently, while driving through eastern Oregon, I stopped by some hot springs near a playa below Winter Ridge. It was so silent along the empty playa I could feel it in my body—a silence so hard I was literally bent by it. Then I heard a whirring engine, like a propeller plane flying low behind me. The sound was deafening. I jerked my head around, certain I would need to dive out of the way. But it was only a flock of ducks careening by, the beat of their wings explosive and mechanical amid the quiet. Once my disorientation passed, I realized I was on my knees between bristly stands of sage, brought down by the difference between what I’d heard and what I’d seen. By the discovery. The silence had allowed me to hear, finally, what ducks really sound like.

Discovery isn’t noisy. It’s active but it’s clean. It’s something rushing into empty space. Without silence I could not have discovered that seven birds winging by could sound like a propeller plane. This is important: it means they always sound like a propeller plane, but the world we inhabit is too noisy to make this discovery. That flock in Oregon didn’t end the silence—it was illuminated by the silence. Silence isn’t an endgame. It’s a catalyst, an opportunity to discover truer things about the world outside or inside your head.