Listen to this story:

Two of them leaped the wall into the backyard where my friends were having a hang: bandits with pistols already drawn so that no one would do anything courageous. Even on the CCTV footage, through which I and everyone else would later see the unfolding, time seemed somehow warped to the surreal pace of small tragedies, where ultimately no one is harmed, no one killed, but the lingering weight of such possibilities makes even the clocks struggle to move. Both the assailants wore bandannas around the lower half of their faces, like highwaymen. My friends relinquished their cell phones and jewelry. Then the bandits had them keep a distance and scaled the wall again with an ease and fluidity that was not absent of grace, and were in and out in what had arguably been three minutes, but which for all of us watching—for those boys I knew from school now forever preserved in the soundless archives of victims—was certainly far longer. I haven’t made a habit of stopping by that backyard in the time since.

At 6 p.m. this afternoon, the government of Trinidad and Tobago was overthrown. The prime minister and members of the cabinet are under arrest. We are asking everybody to remain… calm. The revolutionary forces are commanded to control the streets. There shall be no looting.

These were among the remarks delivered to the people of Trinidad and Tobago on Friday, July 27, 1990, by Yasin Abu Bakr, né Lennox Phillip, a former police officer turned community organizer, whose paramilitary organization, the Jamaat al-Muslimeen, had, just a half hour prior, overseen the capture and command of the islands’ lone TV station, as well as Parliament, where the prime minister and members of his cabinet were being held hostage. Community organizer here being a loose term. The Muslimeen’s attempt at a coup covered a six-day span, during which the police headquarters was bombed, a member of Parliament was killed, intense looting spread throughout the capital anyway, and Prime Minister Arthur Robinson, when ordered by his captors to instruct the mobilizing armed forces to stand down, using the megaphone provided, famously yelled: “Attack with full force!”—an act of heroism for which he was shot in the leg. While under duress, Robinson was also coerced into signing an amnesty agreement granting the usurpers full clemency in the eyes of the law, should anything go wrong with their plan, a scheme so harebrained and legally dubious that it is only with a sense of incredulity that we can imagine him to have signed his name to the agreement, believing that anything can be promised to men who are soon doomed to die.

In 1990 I was two years old, on an extended visit to Trinidad to stay with my grandmother while my parents were in Virginia, where we lived at the time. My grandmother resided in Belmont, on Archer Street, on the same plot of land where she had raised my mother and her other children, though not in the same building: one of my mother’s first orders of business after making some money of her own had been to fund the transformation of the wooden house where she’d grown up into the brick-and-mortar one I would come to know, replete with hard tiling, a washing machine, and a small, fenceless veranda that Granny Sylvia was always warning me not to stand near the edge of, lest I fall. For Caribbean children, the world is for the most part made up of places not to go and things not to touch. It is only imagination that lends the remaining space its endless bounds. My slice of Trinidad shrank even further when my daily walk with Aunty Laverne was indefinitely postponed. Ordinarily we would hold hands for the few blocks to the local parlor shop, where I would get a sweetie, or chilli bibbi—a candy of flavored ground corn sold in thin cones of wax paper—but one day we instead had to stay inside. Many people were staying inside during that eternal week, awaiting further news, except for the looters, who I guess must not have owned TVs or radios. Of that time I have only the impression of hushed concern from the adults, which nonetheless did nothing to dampen the general excitement that characterized my vacation as a whole. I was reportedly so happy during the six months I spent in Trinidad that when, one day much later, a pair of strangers entered our home and told me I had to come with them, I refused and hid behind my grandmother’s leg. They were my parents, back from the US to collect me, and whose existence I had in the meantime forgotten. Only my dad’s promise of a bicycle was enough to lure me away; he was sitting on the edge of the washing machine and miming a pedaling motion in the air. “Bicycle! Look, bicycle.” I agreed to go with the strangers. In my early understanding of material gain as a substitute for love, I had taken a vital step toward becoming a Trinidadian.

As a matter of fact, the amnesty agreement did stand up in the courts, and in the months following the surrender, arrest, and jailing of Abu Bakr and his forces, the cynical validity of their legal loophole would soon become apparent. In a ruling from Justice Clevert Brooks, based on the precedent of governments acting in the interest of restoring national stability, the forcibly signed amnesty agreement was considered part of a negotiated settlement aimed at ending the coup and was thus valid and binding. Which is to say: they were free to go.

Absent of wars, not every nation is afforded so obvious a fork in the road between who they are and who they might have been. One such moment in Trinidad’s recent history was the failed attempt in the late 1950s to form, alongside nine other islands, a West Indies Federation. With the federation’s shared currency, open borders, and collective government, we might have grown resilient against the meddling influences that were the World Banks and IMFs of the time, whose entrapments of debt we have been long in recovering from. The other moment was this coup, which offered us an alternative destiny, not in its potential success (this seems too unlikely), but in the response to its failure. In setting the men free, we exposed ourselves to a mocking revelation, one that is the unspoken fear of any new nation that was once a colony: that we were an unserious country. Our laws were written on paper and nowhere else; they had not made their way into the mettle of who we were. As a Nigerian friend of my father’s once opined upon hearing the story of the Muslimeen, “Say what you want about Africans. At least we have the good sense to round up our traitors for the firing squad.”

By thirteen I was attending my first house parties in Trinidad. My family had finally moved back full time about two years after my initial visit, and the four of us—including my younger sister—lived in Maraval, a quick ten minutes from Belmont and Granny Sylvia, who had suffered a minor stroke in 1994. My sister and I attended the same elementary school until we each sat the national secondary school entrance exam three years apart and matriculated to our respective single-sex institutions.

The house parties would gain traction as rumors, shared from boy to boy, weeks in advance. There was to be a big bashment in Diego Martin, for example, promising pretty girls, lots of dancing, and a chance to wear your cool clothes. I would go, only after much cajoling from my parents, mostly to end up in a flock with my friends, not knowing what to do next. In these new evenings of adolescence there lingered something fraught and ecstatic in that darkening terrain, as if, left to our own devices, we had stepped beyond the eyes of society into a jungle of our own making.

Then soon enough I stopped going to any house parties at all, not for not knowing where they were, but for there no longer being as many for anyone to go to. People were nervous. It was 2003. There was a story of a bandit leaping the wall of a house party in Moka and robbing everyone upstairs. There was an old, recurrent story of a young boy at a birthday party drowning under mysterious circumstances, which, though unsolved and never tied to any bandits, did nothing to assuage the pervading sense of there being dangerous strangers everywhere. Kidnappings were so persistent that they earned a dedicated segment on the evening news. One of the older boys at school, a cricket star from a wealthy family, was kidnapped for several days and held for ransom. My friend’s father was kidnapped, with the kidnappers’ intent, no doubt, of holding him for several days for ransom, but managed to escape from the back seat of the car and flee into the bush. A girl walking to a bus stop, I had heard, was kidnapped for several days and held for ransom but instead killed. There were rumors that the army was involved. There were rumors that narcotraficantes were involved. There were rumors that one of the oligarchic Syrian families—who had suffered the common indignity of having one of their own kidnapped for several days and held for ransom—had flown in a European hit man to deal with the perpetrators, and that was why no more Syrians were being kidnapped: it was just everybody else. No one was really sure.

One place you could be sure was in your house, behind locked doors. Dusk was the time to find out exactly where your loved ones were, and to go from one place to the other only with precautions, like those mice who seem to gather themselves before darting along the edges of rooms so as not to be noticed. Crime made children of us all, shrinking the world until it is comprised mostly of places not to go and things not to touch, times by which to tuck yourself into bed until the bullies said so.

“Attack with full force!” Prime Minister Robinson had said on the first day of the siege, but the armed forces delayed, and it was not until several days later that Abu Bakr and his men were instead allowed to peacefully surrender and were escorted from Parliament. He would live a long life, Abu Bakr, maintaining his compound near the heart of the capital and occasionally suing the government, passing away of old age in 2021. I once met a retired solider who still regretted, with a measure of bitterness, the fact that they had not been allowed to go into the building with guns blazing and nip in the bud the bloody destiny we were instead set upon. Once a government is revealed as feckless, he argued, naked the entire time we thought they were wearing clothes, everyone feels they can do anything, criminals most of all. In the years since 1990, the annual murder toll in Trinidad and Tobago has ballooned to around forty people per one hundred thousand: enough to earn it a recurrent spot in the world’s top ten.

Perhaps this is disingenuous. In fact, the annual murder toll had already been rising before then, and might ultimately have had more to do with Trinidad’s increasing role as a drug-shipment route between South and North America. It was this worsening situation, as well as the lack of economic opportunity for an underserved Afro-Trinidadian population, that Abu Bakr had wanted to stand against. Conditions in Trinidad and Tobago were ripe for a social explosion. The price of oil, our major export, had suffered a drastic decrease in the 1980s. A newly elected government had promised major reform in 1986, but instead had dallied and delayed.

Yet in taking matters into his own hands, Abu Bakr joined a long, ancient list of reckless men—and they have all been men—for whom the state is seen as a matter of opinion, and who always arrive at the same divine insight that the best way of fixing it is to run it themselves. The exact day that Abu Bakr’s insurrection began marked the last on Earth for Gideon Orkar, a Nigerian soldier who some months earlier had seized control of a major radio station and called for the removal of five states from the Nigerian federal union. He was overpowered, imprisoned, and executed by firing squad at around the same time that Abu Bakr was addressing the people of Trinidad and Tobago. Later that year, down in Argentina, army colonel Mohamed Alí Seineldín led his second unsuccessful uprising, a kerfuffle that managed to rack up a death toll of fourteen within a scant twenty-four hours, then sputtered away from general lack of military support and led to his eventual imprisonment. In August 1982 there was air force officer Hezekiah Ochuka, president of Kenya for six hours, who captured a major radio station, explained that the economy was “in shambles due to corruption and mismanagement,” and who in his haste to overthrow the government somehow overlooked recruiting the army to support his cause, and so was overpowered, caught after fleeing to Tanzania, extradited, and executed by hanging a few years later.

So many things can go wrong when attempting to overthrow a government that it boggles the mind that any have ever been overthrown. Whether the conspirators are somewhat bumbling, such as the rebels in Laos in 1973 who had both the airport and the radio station they had seized recaptured by government forces in just a few hours, or tactically excellent, like those in Venezuela in 1992 whose highly orchestrated plan was thwarted, in part, by inclement weather, the challenges they face, always within narrow windows of opportunity, are more likely to triumph before their new regime does. These heirs of Sisyphus are scattered across nations, the futility of their tasks matched in degree only by the seeming inevitability that another one of them, somewhere in time, will try again.

The problem, of course, is that some governments should be overthrown. Except that the matter of deciding which ones those are too often falls upon these juvenile tacticians, nearly comical in their blunders, devoid of equanimity, who even in their occasional successes promise mostly a rearrangement of the previous administration’s faulty parts instead of a replacement. Their sole strategic advantage is usually the general sense of disbelief with which a populace tends to react to such an affront to the system. Always, before the appropriate forces can spring into action, there is that interminable standstill, made longer by the audacity of violence, when the minutes are warped, and all seem to be wondering, Is this really happening?

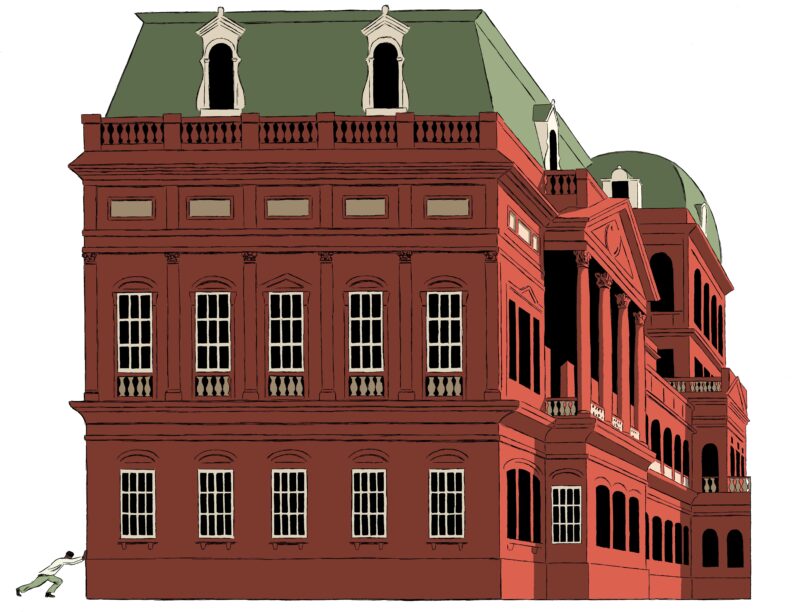

For Americans on January 6, 2021, such confusion was further compounded by a substitution of the cast that rendered the events unrecognizable to many: an insurrection taking place not in some distant brown country with sweating exotics, but in pristine Washington, DC, mostly by “real Americans” holding smartphones, who had booked hotels on their credit cards weeks in advance. Still, in keeping with the theme, they marched upon the Capitol, armed, high on outsize notions of corruption, injustice, and the need for a new order. Arguments that President Donald Trump—at whose behest they were there—did not attempt an actual coup tend to center around how impromptu the happenings felt. But they never have a plan, these people, or the plans are so foolish as to barely qualify, consisting primarily of the two-step process: (1) take over a major building; and (2) I am in charge. They rely on their own failure to prevent them from finding out who they would become beyond that limiting horizon.

So, too, did Americans, then, have their chance to grapple with the question of who they really were, and whether their ideals could withstand the transition from abstract concept into practical application. (Although, to be fair, grappling with “who they really are” is a preferred American pastime.) The nearly four years’ worth of prosecutions levied against Trump ranged in scope and scale from the long shot to the surefire, a federal indictment for attempting to use fake electors, or state RICO charges aimed at bringing down his entire organization of coconspirators. In the end they culminated in nothing more than a graveyard of botched cases, the most ambitious of which was derailed by a romantic relationship between two Georgia prosecutors, one of whom showed the other such preferential treatment as purchasing tickets for a Caribbean cruise. Over this period, the sense of pervading unreality—that an act so brazen, so televised, and so, yes, harebrained could go so unpunished—was for one half of the country quasi-religious proof of illuminated destiny, and for the other an indicator of a world they hadn’t realized was beyond their understanding: in these matters of political surrealism, they had not had as much practice as we of the third world. Most irreverent of all was Trump’s eventual return to the legitimate process of electoral politics and his victory in last November’s election, thereby reclaiming the power with which he could subsequently pardon his fifteen hundred or so coconspirators—a convenience of circumstance that even Bakr himself would surely have envied. As if, in having tried to break into a house by way of a crowbar and smashed windows, Trump instead had resorted to walking to the front door and ringing the doorbell, then had the residents let him and his bandits inside before the police could arrive.

Abu Bakr gave frequent interviews in the following years, never hesitant to express his ongoing displeasure with Trinidad and Tobago’s state of affairs, and to continue to press his case for how much better things would have been under his command. Perhaps his talking points sound familiar: the collapse of law and order, a corrupt nation, the need for someone strong to step in. “Because I was in charge,” he once offered by way of explanation for the lower crime rate in the years preceding his attempted takeover. “Before 1990, I was in charge of the ground, and when I came out of prison I left it.” Whence cometh these cynical prophets, who help to make a mess, then point to it as the reason they should be in control of cleaning it up?

A national psyche is loosened when someone is allowed to publicly flaunt the agreements we have all made with one another. The damage from this loosening does not have to come now, but it does come. My Trinidad is a small one, made of familiar streets, people I already know. It is less that we live in fear than that we live with a sort of mortal resignation, one that stifles the ideas of what is possible long before they reach the potential stages of exploration and play that are the necessary precursors of growth. We understand that any stranger can be the last one you ever meet; that if the police are called, they will arrive late and may want to know why you are bothering them.

Rare is the failed insurrectionist who grows old walking about in the free air. Something satisfied and mocking settles into their gaze as a result, a glint of the successful heist that can never be extinguished. Who are you as a people? this glint says. What kind of a country can you be that would let me get away with this?