After barreling through the relentlessly flat, verdant Punjabi hinterland in a rented Toyota, stopping briefly for naan, kebabs, and petrol, we hit town at three, four in the morning, and at three, four in the morning, music wafts through the still, sticky summer air. Millions[1] gather each year for ten days in the hilly medieval town of Pakpattan, in Pakistan, to commemorate the death anniversary of the twelfth-century saint Baba Farid, celebrating the reunion of man and his maker with qawwali—call it Muslim soul. When Doc, a pal and Pakpattan regular, urged me to join him on the pilgrimage the night before—it’s Baba’s 776th death anniversary, he informs me—I decided to accompany him. I can’t refuse Doc: I’ve got his back; he’s got mine. And who knows? Perhaps Baba will bless me as well. But you have to believe to be blessed.

As soon as we disembark outside one of the friable gates of the walled city, several musicians from Delhi emerge with paan-stained grins to embrace Doc. They insist on presenting themselves again in the afternoon—Doc’s well known in these parts. Then he and I trudge through the labyrinthine alleys to the guesthouse belonging to the right-hand man of the Diwan, the direct descendant of Baba. Tucked away near the summit of a hill, the boxy, two-story concrete structure is modest save for the timeworn, iron-studded wooden doors that lead to a sloped paved courtyard. A few guests remain awake, smoking huqqa, palavering among empty nihari-stained cauldrons. Doc exchanges pleasantries. I hit the sack.

When I wake, around noon, I learn that Doc has gone to the shrine for mysterious morning ceremonies. I do the math: if Doc retired after me, he must have managed no more than a couple of hours of sleep, if any at all. A slight neuropsychiatrist in his sixties with a bristly salt-and-pepper mustache and a bad back, Doc lives for the pageantry of shrine culture. When stirred by qawwali, he has been known to lean into qawwals—singing, swaying, plastic spectacles sliding down the bridge of his nose. At some opportune juncture during the festivities, he intends to drape the bespoke chadors he has prepared over Baba’s grave in a traditional act of veneration. He returns as I’m winding up my morning rituals—black tea, a smoke, bathing out of a bucket in the communal bathroom—then we make hasty arrangements for the performance, or sama, about to take place in the courtyard.

Arranging themselves on the dusty rose rugs scattered across the floor, the band—a nine-strong contingent from Delhi—clear their throats and tune their instruments: a couple of wind pianos the size of small pirate chests, called harmoniums, and goat-skin drums, known as tablas, nestled in their laps. Qawwali might mean “utterance,” etymologically, but it’s much more: celebratory choral vocals over rhythmic clapping, interrupted by improvisational instrumental riffs. While the melodies are informed by Hindu devotional music, the compositions are attributed to the thirteenth-century Turkic poet Amīr Khosrow and include odes to God, to the Prophet and his family, and to the legion of Sufi or mystical saints—Baba is one of the giants in the pantheon. Indeed, Baba’s devotees maintain that Islam was spread across the subcontinent by saints through qawwali.

Others at the guesthouse join us on the rugs: a real estate mogul from Karachi who sports a peaked, velvet hat and a clipped beard; a heavyset character with a prominent mole and walrus whiskers; and a handsome, clean-shaven fellow in a black robe from Manchester, England, who switches seamlessly between Punjabi and a Cockney brogue. Our host is absent—apparently, he had a rough night wrestling a djinn—so Doc stands in as master of ceremonies. As the session gains momentum, he presents ten-rupee notes to the performers with clasped hands; the locals fling cash like confetti. To each their own.

The troupe from Delhi draws on the classical oeuvre of Khosrow. But their rendition is affected by a certain Bollywood sensibility. A jovial character in the back operates what he calls a “banjo,” an electronic contraption resembling a pedal steel guitar that emits a range of twangs. I’ve been into qawwali since I was in the womb—an apocryphal story suggests that my first utterance was a snippet of Sufi poetry—but I need more meat in my qawwali. Only when there’s communion between reciter and listener, is qawwali transcendent. In Pakpattan, the possibility seems palpable, real.

***

That night, as the unforgiving September sun sets over the hill, Doc and I head to the sprawling shrine complex, negotiating bicycles, motorcycles, costermongers, perfumers, and hawkers peddling skull caps, shawls, bangles, beads, toys, posters, incense, dried fruit, jaggery. Already the party has begun: thousands of men, women, children in multicolored hats sprawl on matting beneath the beaded lights that festoon the buildings. Doc tells me of a Sikh retinue that has arrived from across the Indian border—Baba’s verses famously imbue Guru Granth Sahib, the holy book of Sikhism. Another group has reportedly journeyed from faraway South Africa. Who would have thought Baba’s resonance extends to the Cape of Good Hope?

We pass a citadel-like mosque financed by Pakistan’s erstwhile prime minister; Nawaz Sharif must have believed that such an ostentatious construction would earn Baba’s blessings, but he still lost the election. This year the chatter is that our current prime minister, Imran Khan, might turn up.[2] The mosque may be a monstrosity, but the mausoleum is simple: just two graves draped by chadors—one for Baba, the other for his elder son.

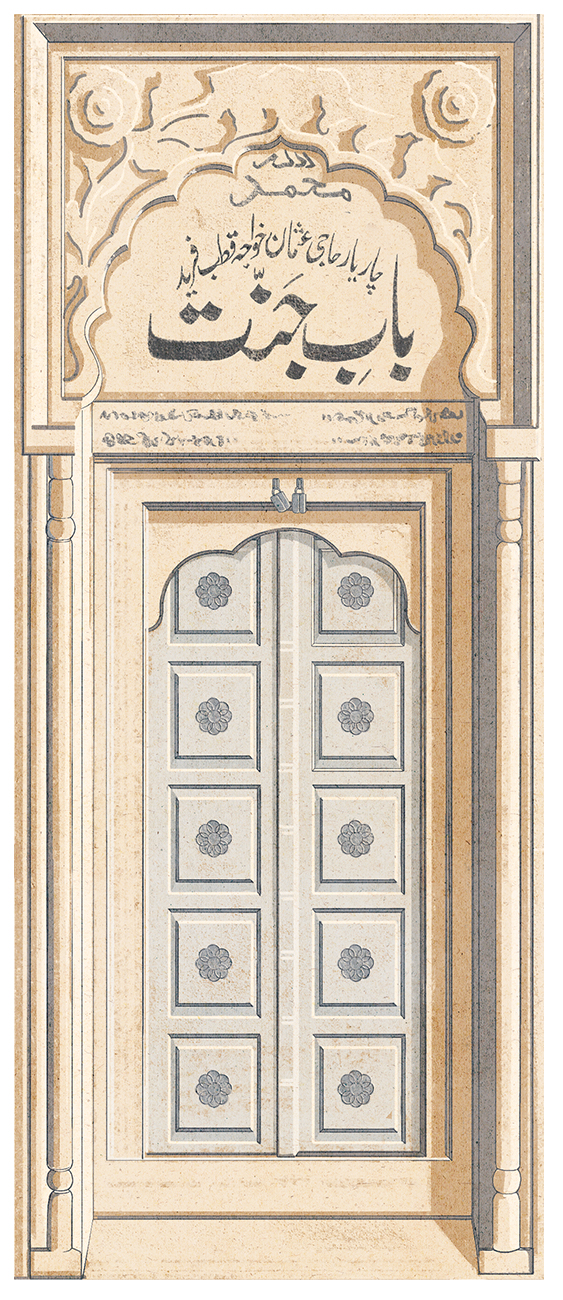

According to Doc, when Baba’s closest disciple, Nizamuddin, received the vision that his guide and mentor’s grave was unfinished, he rushed from Delhi to Pakpattan. As the story goes, he had only one night to complete it—which might explain why the mausoleum is small: there’s standing-room space for about a dozen inside. There are two doors in, one usually open, one usually shut. After working furiously all night, Nizamuddin had a second vision: disheveled multitudes passing through a portal and coming out clean on the other side. The vision was eventually realized by a Turkic overlord years later—he must have sought Baba’s blessings as well. Wrought of silver, the structure is known as the Beheshti Darwaza—behesht, or “garden” in Persian, is typically interpreted as the Garden of Eden. When the Heavenly Gate of the shrine is opened—once a year, for five days, from sunset to sunrise—millions pass through in hopes of redemption—not unlike Porta Sancta in Rome.[3] We are seventy-two hours away from the event.

Some two hundred troupes are in attendance—any qawwal worth his salt must show up to pay respects to his patron saint. Naturally, I’m partial to my hometown cohort—Karachi-based Farid Ayaz and company, the Brothers Saami, the Niazis—but I’m also curious about the locals: Meher and Sher Ali; Rizwan and Moazzam; Maulvi Haider Hassan, the scariest-looking qawwal I’ve come across—he resembles the undead, but I hear he possesses a stentorian voice. Each troupe is allotted only twelve minutes by the authorities: they have to make an instant impact. We catch the local stars, the Brothers Ali, parting the crowd, harmoniums on their shoulders. It’s chockablock—you couldn’t slide a ruler between elbows—but the Cockney, a regular Houdini, squeezes in somehow. The brusque, flinty-eyed master of ceremonies chants, “Haq Farid!” (Baba’s the Truth!) and they begin. The sound system is not quite up to snuff—there is a palpable echo in the microphone and the treble is turned up so their voices sound shrill—but the Brothers Ali know their audience and that’s what matters: when they kick off with a finger-snapping paean to Baba, rupees rain down.

Several sweaty hours in, Doc sways in a trance. But I find myself unmoved as qawwals troop in and out—it’s more circus than samaa. And when Doc starts rubbing his back, I extend my hand. “Time to go,” I say. I’ve got to take care of him if he doesn’t take care of himself.

On the way to the guesthouse, however, we get word that Farid Ayaz has invited us over for a nightcap. I’m famished, but what to do? When one of the most popular qawwals in the country[4] summons you, you show up. We shamble to a quieter, residential canton, where locals rent out their quarters every year, to a cramped townhouse with lime-colored walls.

There we find Ayaz: stout, unprepossessing, and bare-chested, sitting cross-legged in a lungi—an unstitched sarong—on a charpoy adjacent to a noisy refrigerator. As we enter, he cries, “Haq Farid!” Doc cryptically whispers: “Gudri jahan bicha de, wahin takht-e-saltanat,” or “Wherever sits he, whither the seat of power.” I understand that Ayaz’s entire clan is in the room behind the printed curtains—lean young men; full-figured women; bright-eyed children. They travel together and are collectively known as the Bacha Gharana—the descendants of the disciples of Khosrow.

As Doc nestles beside the refrigerator, discussing metaphysics with Ayaz, I chat with his younger, balding brother, Abu Mohammed, over warm boxed mango juice. They have just returned from an American tour spanning the East Coast, as well as Texas, of all places, and Arizona. “They’re into qawwali in Arizona these days?” I ask. “The audience was mostly South Asian,” he says, “but it’s different everywhere—it was mostly locals at Cornell University.” The utterance is again finding global resonance.

I tell him how, as a scholarship student in the early ’90s, I witnessed the meteoric arc of Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan’s career in the States. In just a few years, he went from playing sparsely attended middle-school auditoriums in suburban Virginia to selling out Radio City Music Hall—I remember I bought scalped tickets in a phone booth for the event. By the time of his tragic death, of liver failure at age forty-eight, the laughing Buddha–like Nusrat had become internationally renowned:[5] he counted the likes of Eddie Vedder and Björk among his fans—“He’s my Elvis,” gushed Jeff Buckley—and his silken, incantatory voice lent gravitas to the soundtracks of The Last Temptation of Christ, Natural Born Killers, and Dead Man Walking.

Though not nearly as well known as Nusrat, Ayaz’s father, Munshi Raziuddin, is a legend among the cognoscenti. The elder qawwal possessed an unusual, metallic voice, an encyclopedic knowledge of the Sufi canon, and a striking presence: with his twinkling turquoise eyes; immaculate, pointy beard; and regal posture, Raziuddin looked as if he had emerged from a miniature painting. The night he passed, at age ninety-one, in 2003, I hailed a taxi to Karachi’s Shoe Market, arguably the mecca of the qawwali world, to commiserate with his sons. Farid Ayad and Abu Mohammed don’t quite command their father’s presence but are fine qawwals in their own right.

“Haq!” cries Ayaz from beside the refrigerator. Doc rubs his back. “Let’s go,” I say.

Outside, there’s music everywhere. Transistors blare qawwali from shops and stalls. Roving troupes of weathered musicians busk on street corners. We pause to listen to a bugler. A bagpiper mauls his sheepskin with large hands. A drummer strikes his instrument relentlessly, dug-a-dug, dug, dug-a-dug, like the beating of a gigantic heart. My stomach growls. “What now?” I ask Doc. “Why do you worry?” he replies.

At the guesthouse, cauldrons brim with nihari—that hearty, fragrant stew prepared from beef shank and marrow. This is the langar: God’s kitchen. Nourishment is integral to the ethos of Sufism: for close to a millennium, patrons from monarchs[6] to civilians—anybody hoping for Baba’s blessings—have sponsored free meals at every major shrine across the country throughout the year. The nihari on offer is prepared by Javed Sahab of Javed Nihari, in Karachi, arguably one of the best nihari joints in the world. I’m handed a bowl. I hand it to Doc. He feeds me a morsel of meat pinched in a scrim of naan. It’s divine.

Sustenance undergirds the mythology of Baba Farid’s moniker “Ganj-e-Shakar,” or “Treasure of Sweetness.” When the saint was a boy, Baba’s mother would hide a lump of jaggery—congealed sugarcane sap—under his prayer mat as encouragement. But then the lump began appearing anyway, simply because the boy’s devotion to the Almighty was true.[7] Moral of the story: God provides for the faithful.

There are two kinds of people at the festival: those who are here to bask in Baba’s aura, hoping for a blessing or two, and those who have come to pass through the Heavenly Gate. I’m not quite convinced that one’s sins can be excised by hunching through a doorway—it would seem to me that you should account for your sins standing upright—but what do I know?

When I wake at midday, the day before the Heavenly Gate opens, the guesthouse is packed. A sexagenarian with a neon orange beard and white skull cap is holding forth in the middle of the courtyard, surrounded by a small, rapt, motley entourage. He summons Doc with a wave; the two hug like childhood friends. Known as Hajji,[8] he is, I learn, a fixture—one who has effectively given us the boot: to make room for this great hajji, our host has moved us to the garret. There is nothing to do but sit and listen to him expound on spirituality.

Hajji’s rhetorical style recalls the Socratic method, except he answers his own questions. “Maqsad tha ke yeh sabit kar deta,”he asks in Punjabi,“kikar deta?”—My purpose is to prove the matter. Prove what? He presses on, breathlessly: “The day I went to the shrine it was raining… I stood watching the rain. It hit the dome and gushed down. I raised my head, started drinking from the torrent. What did I do? The others said, ‘Look at this madman!’ But when they realized what I was doing, they followed. When would we have such good fortune again?”

Later, Doc will explain that this parable illustrates the matter of intercession. The Sufi saints who began settling the subcontinent to escape persecution from orthodoxy a millennium ago—figures such as Baba and his disciple Nizamuddin—are believed to be intermediaries between God and man. Entire tribes across rural Punjab retroactively attribute their conversion to Islam to Baba: the Jats, Bhattis, Dogars, Khokars, Wattoos, Tiwanas.[9] They maintain that saints are the fountainheads of spiritual knowledge, as opposed to, say, mullahs. “What does the mullah know?” Hajji asks. “He has his head in the ground and rump in the air.”

A figure of ridicule in South Asian folklore, the mullah represents the variety of Islam practiced by the desert monarchies of the Arabian Peninsula today that forbids intercession, along with figurative painting, public concerts, and women driving.[10] According to the saints, however, the path to the ultimate truth, to God, is esoteric practice, not adherence to formal legal protocols. Qawwali is one such esoteric practice. In this time, when Pakistan in particular, and the Muslim world in general, has been battered by retrograde orthodoxy—a bomb hidden in a milk container outside Baba’s shrine killed six in 2010—at least a million others share the sentiment.

Baba’s devotees also believe they will get exactly what they pray for, if they believe. At a cigarette stall, a smart young man tells me he was admitted to a polytechnic because he prayed to Baba; a lady whom Doc knows from spiritual circles told him she received a wire transfer of 17,200 rupees when she needed 17,200 rupees—not 17,300, mind you. There is, of course, solace in faith for the millions who have been congregating in Pakpattan for close to a millennium. But I, for one, wonder: What if it is just learned behavior, tradition, an elaborate pantomime? What would I pray for if I had the opportunity? Joy, clarity, Doc’s spondylosis, a cold drink? Could the answers be within grasp on the last day of the pilgrimage? God knows.

On our third day, when the Heavenly Gate is to be flung open, I am roused at an ungodly hour: quarter after eight in the morning. I don’t know if Doc’s slept, but he’s raring to go, saffron skull cap already on his head. As soon as Bhatti, the spry, spindly odd-job man, serves me tea, I straggle after Doc like a disciple. At the shrine, we make our way through the side gate—the guards recognize Doc. Inside, I find myself among men in white caps standing solemnly in rows, hands clasped over their stomachs. Everyone seems to be waiting for something. Doc whispers that the Diwan is inside the mausoleum, paying respects to his ancestors.

When the holy man finally emerges, surrounded by policemen and minders, the crowd stirs. He walks a few paces to the perimeter of the stately secondary shrine, rosary twisting in his hand, before settling on a tasseled orange cushion. It appears he’s meditating among small earthen bottles stacked on trays, and I observe him: He’s trim, fair, middle-aged. He wears a sheep-wool hat high on his head, a pair of dark glasses on his aquiline nose. It seems to me he is carrying the weight of the world on his shoulders. His two sons, his heirs, flank him: the young man on his right, reportedly his appointed successor, is slight and wears rimless spectacles—more accountant than academic. The other has shoulder-length hair, wears a kaffiyeh on his shoulders, and has the mien of a wrestler.

As soon as the Diwan blesses the bottles, the jaggery solution within is flung by minders and minions in the air and there is a crush. Doc gets wedged against a marble wall. Pushing my way toward him—“I need to get out of here,” he groans—I grab him by the arm and pull him out. When we reach the guesthouse upstairs, he collapses on the mattress; I hope to God his back hasn’t given way.

But he emerges before sundown, cap lodged on head, just as the motley pilgrims—the real estate baron, Walrus Whiskers, Houdini, Hajji, and our host—assemble in the courtyard. I understand they’re forming a procession to the shrine to ritually drape Baba’s grave. “I don’t think you should go down again,” I tell Doc. “We won’t stay for the opening,” he says. Displaying three exquisite, velvety, forest green chadors adorned with gilded script draped on his arm, he adds, “But I have to go down now.” All I have are my worldly possessions: cigarettes, money clip, phone, and the key to the room, threaded with a red ribbon.

We head to the shrine with pomp and circumstance—a shrill qawwal leads the way, announcing our coterie of senior pilgrims—and though Doc is just ahead of me, there is again a crush outside the mausoleum. Thousands more have arrived, bedrolls on shoulders, garlands in hand—simple offerings for their Baba. They jostle, jockeying for position; the police and the management seem out to sea. From the corner of my eye, I watch Doc being yanked into the mausoleum by our burly host from the guesthouse, the door slamming shut. Then, bereft, I’m swept away.

There is no doubt in my mind that if I falter, I’ll be trampled, trounced; several are crushed to death at the festival almost every year. As I struggle to maintain my balance, I find I can’t breathe—there’s an elbow lodged against my throat. I realize it belongs to Walrus Whiskers. I shout his name, but he doesn’t hear me or, worse, pretends not to. A verse Doc recited in the car from Baba’s oeuvre strikes me: “Farīdā jo taīN mārani mukīāN tinhāN na mārē ghumm,” or “Farid, do not turn around and strike those who strike you with their fists.” Maneuvering my body away, however, I tell myself, The hell with this! I want to be blessed like anybody else. But I also want to live.

Somehow or other, I manage to escape though the side gate without a broken rib or concussion. But I have lost my pal, my guide—and, patting my pockets, I find I’ve lost the key to our room to boot! Doc, sapped and spent, will require rest upon his return—how can I forsake him twice?

Sprinting to the guesthouse, I accost the odd-job man, Bhatti, for a spare key. He looks me in the eye. “There is no other,” he laments. Then he blithely offers to break down the door.

“How would you do that?” I ask.

“With an ax!”

“No, no,” I protest. “That won’t do. That won’t do at all.”

While I light a cigarette and take a few acrid drags, Bhatti produces a bamboo ladder held together with jutting rusty nails. I watch him balance it atop the water geyser tucked in the back of the guesthouse, then scale the rungs like a lunatic acrobat. It seems he is attempting to catapult himself through an air duct leading to our quarters on the second floor. Steadying the ladder’s legs as best I can, cigarette wedged between my lips, I entreat, “Get down”—a broken door is one thing, a broken Bhatti another.

“Don’t worry,” he says, as if this were part of his ritual responsibilities.

“For God’s sake!”

When he slides down, I hear a familiar melody beckoning in the night air. It’s the qaul—Khosrow’s rousing anthem invoking the original disciple, the Prophet’s right-hand man, Ali. And though it figures at the beginning of every samaa, I haven’t heard it since I’ve been in Pakpattan. “Stay here,” I bid Bhatti, putting out the cigarette with my sole. “Don’t do anything!”

Mesmerized, I find myself following the chorus around the corner to the hall of a restored villa. Under the ornate wooden ceiling and painted rafters, I recognize old Abdullah Niazi among the sweaty, spirited

audience—several pilgrims are literally hopping with fervor before the veteran troupe from Karachi. Slicing the air with his arm, Niazi chants,

Darra dil darrra dil-e-dar daani,

Hum tum tanana nana nananana ray

Yalaeli yalaeli yala, yala yala

ray…

“Come into my heart,” the verses might suggest. “My heart is knowing. You and I are one body, one soul.”

But what do I know,[11] and what does it matter? I know that I feel something well within—it might have to do with the mystical import of the words, the vigorous rendition, the electric atmosphere. I know this much: my tear is real and warm.

When I return to the guesthouse an hour later, wet with sweat, I find Doc poised on a plastic chair at the far end of the courtyard, wincing palpably. I dart in the opposite direction, dodging cauldrons and pilgrims in search of Bhatti. Bhatti, Goddamn it, I say to myself.

Just then he materializes like an idea, smiling from ear to ear. He thrusts a palm toward me. There is a key in it, threaded with a red ribbon. Doc, thank God, is sorted.