When a police officer kills a Black person and a camera happens to capture the encounter, I think of Cops, Fox’s infamous reality show that followed law enforcement as they patrolled US streets. The grainy footage, the blurred faces and license plates, the strangely rigorous time stamps in the corner of the screen—everything felt coated in a hazy, drowsy skim. Before it was canceled, in 2020, and syndicated throughout the aughts, Cops came on late, wedged between dramas and sitcoms and the local news. That time slot and the show’s distinct lack of narrative and continuity seemed to signal a shift from fiction and entertainment to something more perverse and gawking. As a young viewer in the 1990s, I did not typically complete episodes; whenever I did, I felt duped. The theme song, which seemed mixed to maximum loudness, invoked “bad boys” and imminent danger (“What you gonna do when they come for you?”), but Cops was essentially a variety show. The policework was directionless and random, guided by whim rather than probable cause—an improvised fox hunt. And the “stars,” the hawkish beat cops whose perspectives we followed, despite their noirish narration and canned charisma, seemed indistinguishable from security guards or traffic cops. They were sentient stop signs, essentially: sophisticated traffic lights. Whether they were chasing someone down or having a conversation with a suspect that wasn’t bleeped into incoherence, I couldn’t discern how one encounter differed from another, why one person was pursued and beaten, while another was cuffed, warned, and let go.

The one thing I could count on in any given episode was that law enforcement would be the aperture through which I saw crime. This is the core premise of the show: to see the public through the eyes of the police. Thanks to the internet and the efforts of countless activists, victims, and bystanders, that premise has grown increasingly untenable. We know that the menacing, chaotic public that Cops insists must be handled with force is a gross fiction generated through standard reality show tricks. (We also now know that the show’s producers coerced suspects into signing consent forms and granted participating police departments editorial approval.) But even with the knowledge that police work is less dangerous than landscaping, roofing, logging, and garbage collection, it remains difficult to watch dash-cam and cell phone footage and not see like a cop. Scrutinizing body language, assessing tone of voice, monitoring hands—the cop gaze directs us even when we watch videos that expose its biases. For this reason, I don’t watch such footage anymore. It’s too limited in scope, too brined in paranoia and power.

The cop perspective isn’t limited to viral videos of police killings, though. It also permeates fiction, especially films. Whereas reality TV shows like Cops present themselves as virtual ride-alongs, films about policing and crime tend to follow cops outside the cruiser, into their lives, into their career cases. I call them “live-alongs.” Both genres traffic in authority, insisting that how cops see is infallible, and that what they see is true. In different ways, the films Queen & Slim (2019) and Empty Metal (2018) target that authority. Both movies insist that looking is an act, not a passive experience—we choose what to see and what not to see. This approach allows the films to probe what and how cops see when they look at the world. Rather than positing a single, coherent perspective whose stability audiences can take for granted, these films explode with perspectives, using the aesthetics of music videos, portraiture, and surveillance footage to bend familiar ways of looking into strange shapes. Both films are flawed, but their visual experiments highlight the creation embedded in sight: vision’s capacity to produce as well as to observe. In the worlds of these films, to see is to act, and to see like a cop is to enact violence.

Directed by Melina Matsoukas, Queen & Slim begins with an awkward Tinder date in a grungy diner. The Black-owned diner is harshly lit and spare. Slim discusses the Black proprietors with pride, smirking at Queen, a defense attorney, like he’s let her in on a family secret. His charm is ineffective: Queen has no appetite and little interest in the date or the restaurant. Earlier that day, the state of Ohio decided to execute one of her clients, and that loss is haunting her. The day worsens.

They exit the diner into a chilly Cleveland night and are stopped by a police officer, who removes Slim from the car and coerces him into allowing a search of his trunk. Slim is annoyed—by the cold, by the inconvenience—and doesn’t do a good job of hiding it, which the cop takes as an insult. Queen steps out of the vehicle to defend Slim, using her legal expertise, and things escalate until Slim ends up shooting the officer dead in self-defense. Queen insists they flee, a plea that has the weight of counsel. A few hours into their escape, they encounter clipped dash-cam footage of their experience, and Queen’s foresight proves to have been wise. In the clip, shown on a cell phone, the scene has a ready-made narrative: routine traffic stop, officer dead, armed suspects. The availability of that summary feels tied to the dash cam as a device: It’s not designed to capture the anxiety of driving while Black, to disclose the racist assumptions that fuel random stops, to probe the absurdity of armed patrolmen enforcing traffic laws. The dash cam produces evidence, full stop, and Queen and Slim look guilty—like criminals, like cop killers rather than survivors.

The footage spreads quickly, turning Queen and Slim from strangers into coconspirators. It’s an awkward fit. They have no destination or plan at first, scrambling between waypoints and struggling to tolerate each other. They are not a couple, or even friends, and their worldviews are disparate. Slim is open and trusting, Queen elusive and suspicious. Matsoukas depicts their journey with dreamlike whimsy: confined to the car, they begin to exchange yearning looks; evocative music plays as they zip down verdant country roads devoid of traffic and potholes. The sky is bright and blue, and the sunlight is constant yet soft, giving Queen’s and Slim’s skin a youthful glow. They are on the run, yet it feels like they are in a hip car commercial. They grow close.

As the duo comes to grips with their new circumstances, they resist the images of themselves that circulate. They do not view themselves as heroes, as the son of a mechanic they hire believes them to be; nor do they identify as crusaders against cops, as they inform a white couple that reluctantly stows them away. Their most spirited defense is against the mechanic who charges them extra to repair their car. He upsells his service because he recognizes them and disagrees with their flight. Queen and Slim insist they didn’t have a choice, an argument he scoffs at. They capitulate and pay the upcharge.

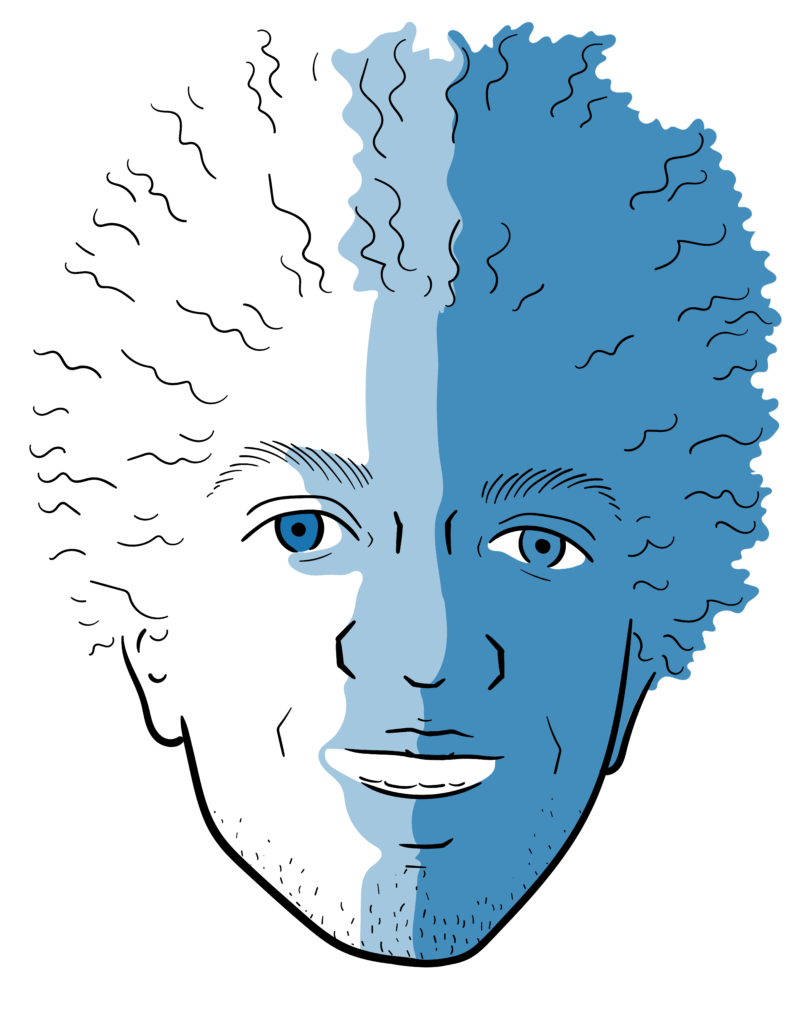

The one image of themselves they don’t contest is a photograph they take at the mechanic’s shop after their car is repaired. The portrait is suave and theatrical, the kind of too-cool picture intended to sell an exceptional day or night as an MO: This is how we do. Dressed in a studly tracksuit, Slim leans back against a sleek 1973 Pontiac Catalina and tosses the camera a stony gaze, while Queen, perched atop the vehicle in a form-fitting animal-print dress, admires Slim with longing and awe. This is their memorial to themselves, their self-written legacy. Slim says the photo will be “proof we were here,” a statement that gives the coolness of the photo an air of correction. If the dash-cam footage is the official record of their lives, the photo is the revisionist version. They do not keep the photo.

Where Queen & Slim seeks to humanize reluctant criminals, directors Adam Khalil and Bayley Sweitzer’s Empty Metal aims to criminalize the police state. The plot revolves around three blurred photos that are laid across a coffee table like evidence during a police interrogation. The three figures in the photos are George Zimmerman, Daniel Pantaleo, and Darren Wilson, and the obscuration is likely a function of libel law, but the overall effect is that the men are rendered faceless. The film’s main characters, members of a rudderless noise band, are out to assassinate this trio as part of a scheme to battle the surveillance state, and the viewer, like the band, must learn to look at the targets differently.

The band is radicalized by an underground network of militant psychics. The psychics—a Rastafarian hacker, a Native activist, and a white sovereign individual—are more symbols than characters, but they have a sense of purpose that the band lacks. They’ve fought the state through computer hacking, civil disobedience, and protesting, and have come to believe that their enemy is too powerful to confront head on. Their solution is guerrilla warfare, and their secret weapon is something on the fringes of a drone’s crosshairs: regular people. Enter the band, who commit themselves to becoming “empty metal,” human weapons in the psychics’ invisible insurrection.

Sweitzer and Khalil portray the band’s radicalization through experimental montages that overflow with hacked, offbeat imagery, of which the photos of Wilson, Pantaleo, and Zimmerman are just a small part. The directors re-create infamous police murders as trippy animations that look like tutorials in a video game. The faceless cops and victims that populate the animations seem homogenous and stiff, as if they were acting out predetermined roles.

These sequences appear alongside images of unarmed Native protesters shot in profile contra armed cops in formation and slow-motion images of boiling soup. Deadpan voiceovers and droning ambient music link these scenes to the simmering rage of the band, giving the film a sense of hallucinogenic dissociation. To see themselves differently, the band must view the world anew as well.

It works. “If anyone could know all this—” one band member says, referring to Pantaleo’s documented choking of Eric Garner, “Why the fuck is he still alive?” another finishes. The exchange is clearly directed at the audience. Despite these scenes and perpetrators of police brutality being warped and distorted, they remain identifiable, which feels intentional. Letting killer cops and their proxies go free is an American tradition, a collective choice. We recognize these episodes because our inaction made them possible. This is a sweeping provocation, but it feels more actionable than the dignified martyrdom of Queen & Slim. After all, the conflict in that film boils down to a contest between the dash-cam footage that initiates Queen and Slim’s flight and their enduring likeness, seen on a mural at the film’s end, that proves they were more than fugitives: a wrong image versus a right image.

As far as character arcs go, Empty Metal has a lot in common with Cops in that there are no arcs or characters at all. But ultimately its provocations are instructive. While Cops presents its leering, disciplinary perspective as objective, and Queen & Slim settles for prettied respectability, Empty Metal posits that that vision is tenuous. There is no Goliath-toppling kill shot in Empty Metal, no final showdown, no everlasting justice. Instead, there are sight lines, and they are always changing, always treacherous. I find that view to be as hopeful as it is grim. The crosshairs may catch us, but they will never contain us.