All streets in time are visited.

—Philip Larkin, “Ambulances”

When I was growing up in the pre-computer England of the 1960s, various board games promised “all the thrills and spills” of Formula 1 or football “in the privacy of your own home.” There was even a brewing company whose slogan—“Beer at Home Means Davenports”—offered the chance to get drunk on draft beer without the irritating conviviality of getting your round in at the local pub. This desire for voluntary house-arrest has since been so thoroughly sated by the internet that we now expect to be able to get, do, and buy almost everything without having to leave our lairs. But who’d have thought that you could be a stay-at-home street photographer?

I became aware of this breakthrough only when Michael Wolf (born in Germany, 1954) received an honorable mention in the 2011 World Press Photo Awards for work made sitting in front of his computer terminal, photographing—and cropping and blowing up—moments from Google’s Street View. Ironically, Wolf fell into this way of working when he moved from Hong Kong to Paris, one of the great traditional loci of street photography, after his wife was offered a job there. He discovered that the city had nothing to offer him photographically. Compared to the teeming, constantly changing cityscapes of Asia, Paris was an open-air mausoleum that had remained largely unaltered for over a hundred years. Haussmannization had radically transformed Paris in the mid-to-late nineteenth century, but pockets of the “old” Paris photographed by Eugène Atget will be familiar to any contemporary visitor. Atget famously made his living by providing “documents for artists,” and Wolf was alert to the connection between Atget’s painstaking survey of the city and the possibility of deploying Street View’s comprehensive—if uncomprehending—curb-crawl for his own artistic ends.

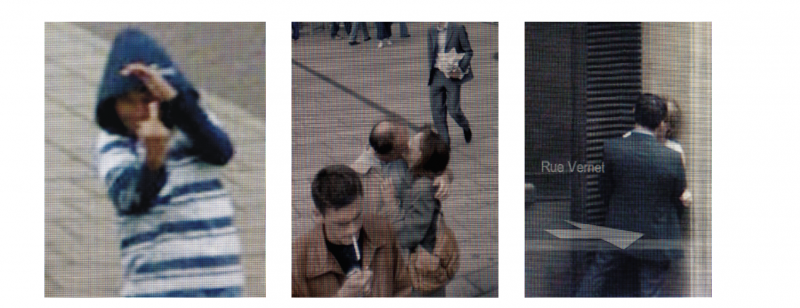

He saw quickly that the indifferent gaze of the Street View camera randomly recorded what he called (in one of the series resulting from this discovery) “unfortunate events”: altercations and accidents, pissings and pukings, fights and fatalities. The Street View cars that Google deploys, each equipped with fifteen lenses mounted on its roof, are like the ambulances in Larkin’s poem: “giving back / None of the glances they absorb.” Actually, it’s not just glances: while the cars usually go about their business unnoticed—or at least unheeded—occasionally people respond to their all-seeing presence by giving them the finger (hence the title of another of Wolf’s series, Fuck You).

A number of amateur websites sort, collate—and direct viewers to—glimpses of naked women in windows and so forth, wherever they have been seen by Street View, and Wolf might have been expected to pursue the easy hyena option by mopping up this kind of visual carrion. He preferred to stalk his own prey, methodically going down every filmed street in Paris, combing through mile after uneventful mile of boring footage in search of moments that may or may not prove decisive. (Again I am reminded of a childhood precedent: an ad for the yellow pages phone directory that quaintly urged you to “let your fingers do the walking.”) A quest that seemed destined to prove the accuracy of Michel Houellebecq’s verdict—“Anything can happen in life, especially nothing”—turns out to represent not a break but a continuity with Wolf’s earlier work.

In The Transparent City (2008) Wolf had taken telephotod images of high-rise buildings in Chicago, a project that was itself an extrapolation from his earlier survey of the architecture of density that had fascinated him in Hong Kong. The results were flattened patterns of light and line with occasional Hopperesque views of humans stranded in the immensity of urban geometry. Imagine Wolf’s delight when he saw that in one of these apartments a large TV was actually showing Rear Window! Yes, there was James Stewart staring into someone else’s apartment with his telephoto lens, photographed by Wolf with his. (Was this just old-fashioned photographer’s luck? Did the occupant of the apartment have this on permanent freeze-frame as a generous gift and ironic reprimand to anyone who happened to be spying? Or was there an element of Doisneau-esque contrivance involved?) Later, as Wolf was looking at some of the other images through a magnifier, he saw something that had escaped him when making the picture: a resident in one of the windows of one of the apartments in a distant building had spotted what he was up to—and was giving him the finger. Pioneers of candid photography—Paul Strand on the street, Walker Evans in the subway—had gone to awkward lengths to work unnoticed. For Wolf in both The Transparent City and the Street View work, the fact of being recognized and abused—the moment people realized that they were being photographed—proved incentive and invitation as much as insult. Having spotted this magnified, pixilated figure, Wolf proceeded to comb through every window in every apartment in the Transparent City to see what other intimate details had been unwittingly revealed. Perhaps film could yield potential images that ordinarily observed reality did not? The results, for the most part, were disappointing: boredom, serial isolation (Hoppers, Hoppers everywhere) as people watched TV or stared at computer screens. There is also the unremarked possibility that another kind of reciprocity was at work: some of those people concentrating hard on their computer terminals could conceivably be scanning Street View, making their own images.

When Wolf got that honorable mention, the response was immediate—and overwhelmingly hostile. There was, however, some division within this negative reaction. Moderates claimed that the work, composed of systematically gathered images, wasn’t actually photojournalism in any sense. And Wolf’s most aggressive critics argued that he was no longer a photographer at all! To the first accusation I would respond that while the news part of the content might be minimal (crashes, brawls, mishaps), the way of making these pictures was itself a newsworthy story and an up-to-the-minute investigation. To the second, Wolf happily responded that he was part of a long history of artistic appropriation of which his detractors were presumably unaware. (James Joyce famously said that he would happily go down in history as a scissors-and-paste man.) The art in this latest technological manifestation of visual sampling was in the crop, the edit—an edit that could actually enhance or even create a Blow-Up-like sense of implied, unresolved, and potentially incriminating narrative (feet and limbs disappearing out of shot). There was also a comparable sense of urgency, for it turned out that Google tended to scrub exactly the kind of unfortunate events that fascinated Wolf, so that within twenty-four hours a brawl that had broken out on a given road was tacitly disappeared (which means that there was some kind of news dimension to the content after all). Hence the addictive, virtually Winograndian urge to patrol the same streets repeatedly. But whereas David Hemmings in Blow-Up or Stewart in Rear Window were obliged, in their different ways, to confine their attention to one tiny fragment of their respective cities, Wolf had at his disposal a surveillance project of unprecedented magnitude that, in turn, is just a single strand in the larger network of state and corporate monitoring of daily life. Works of art that seemed, paradoxically, to undermine the role of the artist as an individual creator were predicated on another paradox: the near extinction of available privacy for citizens whose faces were automatically blurred—whose identities were thereby extinguished—by Street View’s software. (But it didn’t stop there; as Wolf discovered, this software sometimes failed, so that people’s faces remained visible and they became, in Diane Arbus’s phrase, “anonymously famous.”)

Needless to say, Wolf’s curiosity soon ranged beyond its local origins. If he grew bored prowling the streets of Paris, he could zoom off to some other city in the world and see what was happening there. While each place tended to be marked by particular kinds of incidents (lots of bicycle accidents in Holland), broadly speaking, the same things—glimpsed nudity, violence, sudden faints—break out of the drab uniformity of life wherever one happens to be. In tandem with Wolf’s instant pan-global drift, this viewer soon discovered that there were a number of people doing pretty much the same thing as Wolf.

Almost exactly the same thing, in fact. If you scoot around the internet, checking out Wolf’s stuff, it will not be long before Google—the search engine, not the camera-cars—nudges you in the direction of Jon Rafman, who is working with the same source material. His website actually features crops from some of the same Google scenes as Wolf’s—so whose pictures are they? That, in Rafman’s beautiful formulation, is part of the conceptual underpinning of this shared activity. These, he writes on his website, are “photographs that no one took and memories that no one has.”

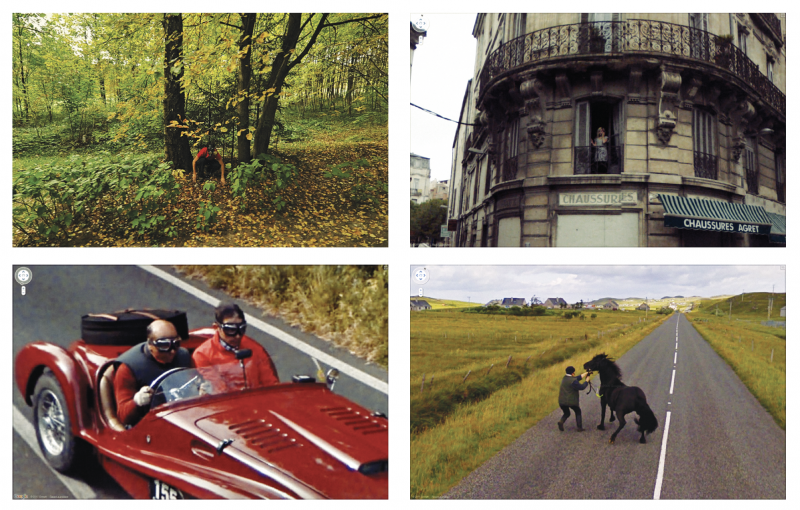

There are, however, broad differences in approach between Wolf and Rafman. Arranged in series, Wolf’s work retains something of the systematic nature of his search; while sharing Wolf’s fondness for certain things—people flipping the finger, roadside hookers, and traffic accidents—the style of the thirty-year-old Rafman seems far more aleatory. One gets the impression not simply that he lacks Wolf’s formation as an old-school photographer but that he has, quite possibly, never set foot outdoors, that his knowledge of the world derives entirely from representations of it. Even this is to understate matters somewhat, for while Rafman is apparently based in Montreal, he might as well be gazing at life on Earth from a distant space station—and gazing on it longingly. There is something extraordinarily poignant about this apparently haphazard collection of grabbed snaps from everywhere and nowhere in particular. It is as if the technological relay that brings the work into existence gives vent to a nostalgia and homesickness so intense that the longed-for original becomes impossibly intimate, mind-bogglingly remote, and—as a consequence—unfathomably strange. Like Wolf, Rafman insists that “it’s the act of framing itself that gives things meaning,” but then he goes further: “By reintroducing the human gaze, I reassert the importance, the uniqueness of the individual.” And where does this idea of the individual come from? From photography, of course! Excited by the way images lifted from Street View possessed “an urgency [he] felt was present in earlier street photography,” Rafman mines Google to uncover a parallel history of the medium, in which repeat images from Lartigue (a goggled couple googled in a speeding vintage car), Winogrand (who in his last years, driving/photographing around L.A., became a kind of one-man Street View), and other masters mingle indiscriminately with fascinating snapshots—all yanked free of their original anchoring in time and place.

Here I concede my own old-fashioned middle-agedness. Exciting though they were, I found it unsatisfying and difficult to see Rafman’s and Wolf’s work only on-screen, as though lured against my will into this virtual and ever-more-mediated vortex. And then I found myself in San Francisco (the actual city, I mean, with real people, buildings, and everything), where, quite by chance, I happened upon Doug Rickard’s A New American Picture at the Stephen Wirtz Gallery. Any doubts as to the artistic—rather than ethical or conceptual—merits of this new way of working were definitively settled by Rickard’s pictures. Their effect was immediate, intense—and, to my surprise, enduring. It was William Eggleston who coined the phrase “photographing democratically,” but Rickard has used Google’s indiscriminate omniscience to radically extend this enterprise—technologically, politically, and aesthetically.

The spots chosen by Rickard are in the economically ravaged fringes of cities: the wastelands and desolate roads that form the constant backwash of America’s broken promise. These places are populated by stray figures, strays both in the sense that they have wandered into the car’s 360-degree view, but also because they have strayed from the path of prosperity—or, more accurately, the path to prosperity has passed them by. Loping baggily across the road, these forlorn figures look like they will never quite make it to the opposite curb, as if they have been cut adrift, are stranded perpetually in the limbo of late capitalism (after which comes more capitalism).

The series contains obvious echoes of photographs made by Evans under the auspices of the Farm Security Administration in the 1930s, with the vernacular signage—american collision, super fair—serving a similarly choric function. The shifting spirit of Robert Frank seems also to be lurking somewhere, as if the Google vehicle were an updated incarnation of the car in which he made his mythic mid-’50s road trip to produce his photographic series The Americans. As with these two illustrious predecessors there is a strange beauty—sad, lyrical, unconsoled—in this latest virtual installment of the American photographic safari-odyssey. We end up not with the pristine clarity of an Evans or the hurried, sidelong glance of a Frank, but with a shimmer and blur, a defining imprecision or washed-out residue of something that I am tempted to term “painterly” (though I’m conscious that when people describe photographs as “painterly” they tend to mean “photographic”). Colors are simultaneously enhanced—especially the green of trees—and drained by whatever processes Rickard has put them through. Sometimes the sky gets rinsed out, other times it has a vestige of the turquoise ache of the Super-8 of old (the very color of optimism, of economic growth for all). All of which contributes to the sense that we are seeing ghost towns—or ghost streets—in the process of formation. A phrase of Prospero’s—the very name contains the root idea of prosperity that fuels the American Dream—from the end of The Tempest hovered in the air of the gallery as I stared at these pictures: “This insubstantial pageant faded…”

One image in particular seemed hauntingly familiar, and drew Prospero’s words to it as though they were an imaginary, accidental caption. It showed a guy in a wheelchair, wearing a Stetson, gazing up at the camera. He is slightly fuzzy due to one of the alchemical quirks and glitches of the various technologies involved, and appears as if he is vibrating. (As the curator David Campany pointed out in an essay on Rickard’s work, the Google images are “all from 2.5 meters above the ground, a height that is neither human eye-level nor the dispassionate ‘overview’ we associate with surveillance.”) It took me a while to work out why it was so familiar—had I actually seen it before in some unremarked context?—and then, just as I moved on to a neighboring image, it came to me: it recalled Paul Fusco’s slightly blurry pictures of the people lining the tracks of RFK’s funeral train as it made its way from New York to Washington, D.C., in 1968 (the year of Rickard’s birth). Instead of people gathering along a set route as the body of the dead senator passes by, there are just these randomly taken people, indifferent or surprised, as the little car with its periscope camera goes about its business, covering every street in the land, as inevitable and accidental as death itself: “The solving emptiness,” in Larkin’s words, “that lies just under all we do.”