It’s always been ironic to me that one of the last perceptive hurdles in equality between women and men’s sports has to do with emotions. I say perceptive because I’m not referring to the persistent pay disparities, or the discriminatory treatment of trans athletes, or the many gender-based prohibitions that inform how women are seen as lesser than their male counterparts, but how the in-game actions of women and men are interpreted differently in our culture—how it is we watch them.

In men’s sports, we tend not to criticize the players’ emotional responses to the game. They scream in triumph, pleasure, frustration, and camaraderie, going back and forth with chippy animosity that might escalate into confrontational anger, fists flying. There’s sneering, shit-talking, stalking around behind refs and opponents. After a big bucket, there’s cartoonish pride; they pose like bodybuilders and pantomime sleep, two hands tented softly under a cheek. There’s plenty of complaining, staggering around clutching heads and chests in despair. Even tears fall occasionally. In women’s sports, by contrast, the expectations on how athletes should emote are many, even if they are unspoken and often conflicting.

In the Finals matchup of the NCAA Women’s Final Four tournament last year, as the fourth quarter wound down, then LSU senior, Angel Reese, trailed Caitlin Clark around the floor and waved her hand tauntingly in front of her face to mean “you-can’t-see-me,” a gesture borrowed from WWE wrestler John Cena. She was also borrowing it from Clark, from a couple games earlier, when Iowa beat Louisville to enter the Final Four. I was at that game, and I laughed at the timing and precision of it, this petty gesture saved for deployment at exactly the right time. It reflected Reese’s on-court aptitude; she knows how to capitalize on the momentum of a moment, she’d been doing it all night for LSU. And as a competitive barb, the callback was perfect. Clark saw it this way too, a gesture made in the spirit of friendly competition. But online, in the fallout of that game, viewers lost their minds. Reese was called “classless” by multiple sports journalists (none of whom typically covered women’s basketball), an “idiot” by former ESPN host Keith Olbermann, and worse (none of which bears repeating). Many, including Reese, called out the racist double-standard: Clark’s initial face wave had been celebrated, including by Cena himself.

The conversation happening around that electric final should have been about the well-matched competition. To return to the Latin word competere: it should have been about two athletes striving together. On the court were two athletes at their best, locked tight and going stride for stride, shot for shot, in synchronicity. One could quickly turn the other’s gesture of triumph into defeat just by miming it back at her. Yet, the discussion surrounding the game was about the distance between Reese and Clark, and the emotionally administrative work in how a woman is allowed to win.

*

The WNBA has had its share of formidable rivalries. It’s a small league: with 144 players across twelve teams and thirty-six games in a season, people figure each other out. One of the more intense push-pull dynamics was that of the Mercury’s Brittney Griner and recently retired two-time NBA Champion Sylvia Fowles, both centers, who ended up going head-to-head for a lot of physical, hard-fought games. Another can be seen in the iconic photo from the 2021 WNBA Finals of the Chicago Sky’s Kahleah Copper, bent at the waist to stare down the Mercury’s Sophie Cunningham at eye-level, as she tries to get up off the court.

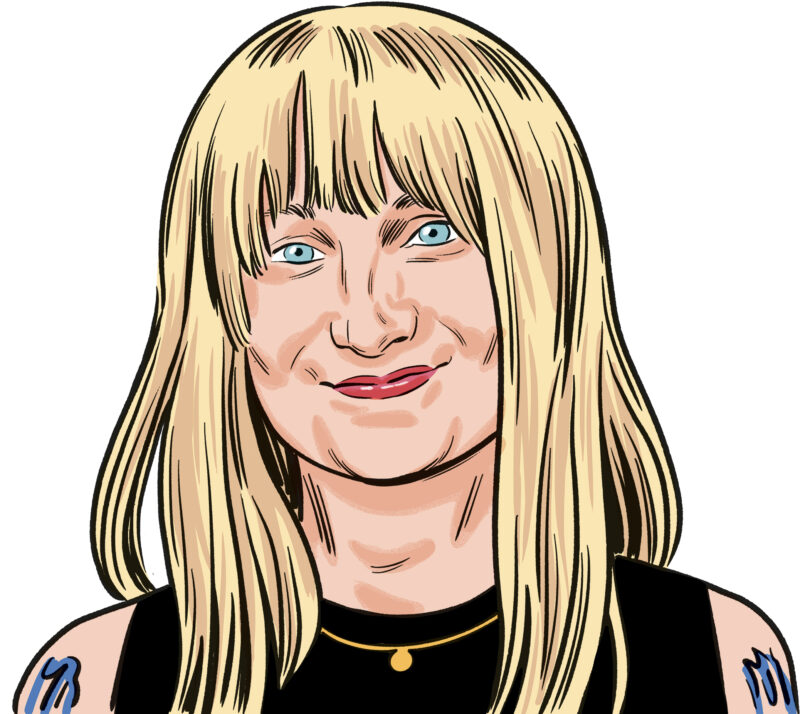

Then there’s Diana Taurasi, a tough and outspoken league legend now in her twentieth season with the Phoenix Mercury, who has had her fair share of enemies. She’s the league-leader in all-time fouls (1,650) and an elite trash talker. She once promised a referee whose call she didn’t like: “I’ll see you in the lobby later.” Commenting on Taurasi in 2021, WNBA point guard Sydney Wiese said: “You just hear her voice. You constantly hear her voice.” W giant Sue Bird, who played in the league for nineteen seasons and has known Taurasi for twenty years, actively encouraged her teammates not to respond to Taurasi’s trash talking, knowing how much she thrives on it. “I see people poke the bear, so to speak, I know she’s going to have a big night,” Bird told The Athletic in 2019. “So when I’m on the other side, I tell all my teammates: ‘Do not talk trash. You’re going to want to. She’s going to push you in ways that’s going to make you want to.’”

If rivalries last as long as the best W careers do, they tend to grow into a mutual respect, as is the case with Taurasi and Maya Moore, who both played for their respective franchises their entire careers (Moore was with the Minnesota Lynx until she retired in 2018.) Because of a change in the league’s playoff format in 2016, the Lynx and LA Sparks faced each other in back-to-back playoffs (before that, teams in the same conference didn’t play each other in the Finals), where Moore and the whole Lynx team developed a fierce rivalry with Alana Beard and the LA Sparks. Moore credits Beard for pushing her to be a better player as a result. “We make each other work. There’s a lot of respect between us,” she said in 2017.

Moore also credits the great competitor Lisa Leslie, who inspired Moore’s physically dominating style, and who was often turned into a villain by the media as a result. “I watched her a ton. I loved her confidence; she was a dominant player that played with a little attitude—blocking shots, scoring inside, having that look in her eye. You knew she was about business, and her teams won,” Moore recalled in 2015, when Leslie was inducted into the Women’s Basketball Hall of Fame.

Leslie, in her day, was relentlessly booed by hometown fans when she and the Sparks came to town, especially in Seattle. Leslie and Lauren Jackson, a forward for the Storm, got tangled up at the 2000 Sydney Olympics, where Leslie was playing for the US, Jackson for Australia. Jackson’s fingers got caught in Leslie’s ponytail extension and she flicked it down onto the court. Leslie picked up the extension and flung it, maybe accidentally, into the face of a photographer. He held it up to cheers from the crowd.

Leslie was a formidable player, a dynamic mix of strength and tenacity, and a single-minded professional who was intent on always improving. She’d get to the team’s practice facility—which the Sparks shared with the Lakers—two hours ahead of Kobe Bryant and Shaquille O’Neal (who got there at 7 am, when the building was supposed to open) to practice. There’s a sense, going over old feature reporting on her, that Leslie was reviled as a villain. Most of the disdain seems to spring from her visible, undeniable confidence, and the seriousness with which she took her craft. She was meticulous about nutrition—which is now a W and NBA norm, but was not in late-90s and early 2000s—and training. Minnesota Lynx coach, Cheryl Reeve, called her a handful on the floor and the greatest center the league had seen. Leslie was also the first woman to dunk, once doing it three times in a row during 2002’s All-Star Game practice at the request of screaming fans (who she then ignored when they tried to call her over). When she was named MVP of that game, the crowd of nearly twenty thousand people booed.

That oscillation between appreciation and scorn for visibly confident athletes isn’t new, players who know they are talented, recognize the rarity of their physical ability and mental acuity, and are (understandably) assertive as a result. And while the way we view these athletes isn’t uniquely reserved for women (we elevate and disparage male athletes with comparable passion), it is only women, elite athletes or not, who we expect not to express their full range of emotions. To diminish their reactions instead of embodying their gifts and being loud with their skill, brash with their talent.

*

A recurring criticism of the WNBA is that it actually needs more rivalries. It would stand a better chance at winning viewers over from the NBA and its summer offerings, the thinking goes, if it could boast a few additional juicy conflicts. The league’s always had plenty of contention, but what has changed in recent years is the visibility of those conflicts. With more nationally broadcast games (the WNBA used to have only a handful per season), streaming services, and social media, we have more access to impassioned play from women than ever before. But what’s clear is that we’re no more comfortable with it than we were twenty years ago. Take for example the broadcaster Charles Barkley, who, prior to Game 1 of the NBA’s Western Conference Finals earlier this week, blasted WNBA players for “hating on” Clark. Instead of permitting these women the same degree of competitiveness afforded men, he says other W players should treat her with a sense of gratitude, given the new wave of attention she’s brought to the league. “Y’all petty girls,” Barkley said dismissively. “Y’all should be thanking that girl.”

We want women to perform, but to perform in very particular ways, to police themselves, to pick and choose their feelings even in the heat of professional-level competition; we think it should be joy and not anger they feel, or if it is anger, then not the kind that leads her to snap at the refs or storm down the floor in an honest flash of frustration. We end up tearing down the fiercest, most vocal competitors, and reaffirming the tired trope that we’re only interested in women if we can govern their emotions. As successful as the W and its athletes have been in pushing the sport forward to greater popularity, the limits we face when interpreting these players are dragging it backward into a much more boring and regressive place.