1.

How do you make a day that feels like a harmonious unity

instead of a chaos?

—Scott Nearing, letter

to Helen Nearing, circa 1928

Not everyone has the problem of too much time. Some people are in medical school. Me, I am a freelance writer, which means that every day stretches out in front of me like a wide sheet of butcher paper. On bad days, blank is the best word for it; after all, blank is just a neutral version of oblivion, one emotional inflection away from utter despair. The desert, the moon, Antarctica: these aren’t places anyone lingers long, if they can help it. Too often, you end up with a stitched-together creature of a day, the long hours an unmarked landscape in which you’re chased around by a monster of your own making.

These days, I’m not the only one in the coffee shop with a haunted look, a complicated relationship with my watch. But it’s not that we don’t have anything to do. It’s just that absent babies and/or a full-time job, the days feel loose and baggy around us. We work from home, or we moved back in with our parents. We’re on food stamps; we’re part-time at Starbucks for the health care; we’re hiding out in grad school, getting a master’s degree that will actually make us less employable (experimental theater!); we’re home for a few weeks before we go out on tour again; we have half a job, or three tenuous quarter jobs; we’re twenty-eight-year-old interns; we’re our more-successful friend’s personal assistant.

And we are always on the computer. It used to be that staring intently at a screen meant that you were busy and important, but the person who fills up her own days knows better. For us, the internet is a sneaky marketplace where we exchange perfectly good hours for stupid facts (did you know Michael Crichton was six foot nine?) and come away feeling like we’ve made a bad bargain. If you had to conceive of the exact opposite of a harmonious unity, the internet would do nicely.

2.

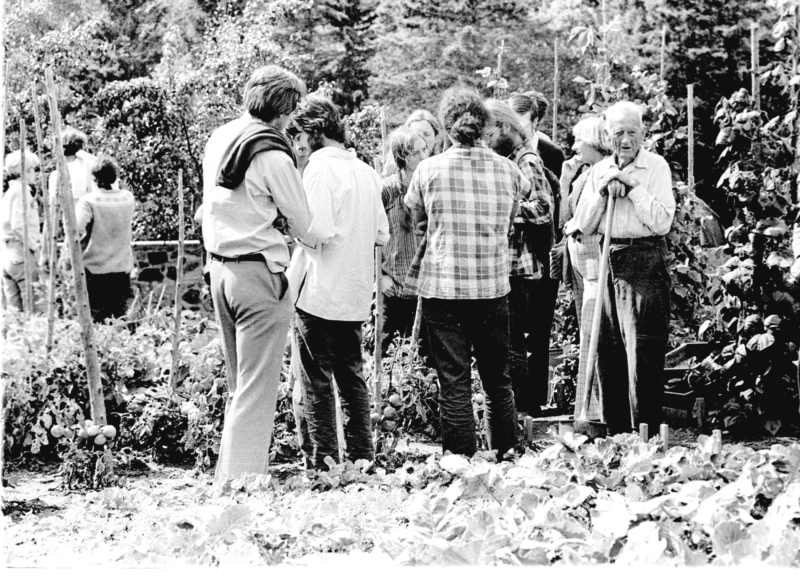

This mood makes me thirsty for memoirs, for the comfort of the inevitable through-line of a life. Reading Scott and Helen Nearing’s Living the Good Life, their self-mythologized account of their time as New England homesteaders in the 1930s and beyond, with its purposeful chapters on terraced gardening and stone-wall building and dealing with ornery neighbors, you get a sense of two lives organized by fate, pushed forward by smart decisions. Whether this brings you comfort or despair depends on your personality, and what you’ve gotten done today, perhaps.

If it helps, consider the pre-Scott Helen. In 1921, when she was seventeen, Helen Knothe went to theosophist summer camp in Holland. All the young practical idealists were in a tizzy about a handsome young man from India. Jiddu Krishnamurti had been plucked from the slums of Madras by prominent theosophists who sensed that he might be the next corporeal vessel for the coming World Teacher. At the camp, surrounded by fervent theosophists, Krishnamurti was an awkward, overwhelmed celebrity. Helen was cute, strange, given to mystical daydreams. Krishnamurti watched her win a footrace, and she asked him to sign her autograph book. At the end of the week, they sat together in the sand dunes surrounding the camp. The maybe-messiah put his handkerchief over his face so he’d be less nervous. He told Helen that she’d “joined the trinity of his loves” (along with his brother, his adopted mother, and his British patron). He promised to write.

At first, Krishnamurti sent letters all the time. His tone vacillated between ardent (“I love you with all my heart & soul & shall always do so. Bless you”) and instructive (“You must keep your body as clean & as pure as your conscience… Take exercise every morning for about 20 minutes. Never be influenced by anybody, not even by your dearest friend. All your friends must be pure in mind & body”). Over the objections of her family, Helen joined Krishnamurti in Europe, and spent the next few years traveling through India and Australia with him and the theosophical elite.

In 1923, when Krishnamurti started suffering inexplicable spells of excruciating pain, Helen was the one he asked for. She would lie in his bed, squeezed between him and his brother, caressing him and whispering calming words. Sometimes he seemed to confuse her with his mother. Other times, not so much: “What a dirty astral body I must have,” Helen wrote in her diary one night. Everyone agreed that the agony must be part of his preparing to become the vessel for the coming messiah.

But that didn’t happen. Instead, Krishnamurti grew distant from her, and eventually from theosophy in general. In 1929, he renounced his own messiah-hood, and denounced the concept of saviors in general (which, of course, only made some people more devoted). Helen moved back to her parents’ house in suburban Ridgewood, New Jersey, and theosophy moved on without her. When she saw Krishnamurti again, decades later, he seemed not to remember who she was.

(a)

For a little while, I was hanging out regularly with two teenage girls in a small town an hour south of Marrakech. After we’d made the day’s bread and swept the courtyard, there wasn’t much else to do. We’d go on long walks to the grazing fields on a hill above town, and sit there for a few hours, watching the cows chew. Or we’d re-watch the four-hour DVD of their cousin’s wedding.

These girls weren’t an exceptional case, either. The Moroccan government had been pushing hard for equal education for girls, and Fatima-Zohra and Amel had been (along with their brothers) the first in their family to finish high school. But Morocco hadn’t figured out what to do with these rural, educated girls once high school was over. There weren’t any jobs, even for the men; university was expensive and far away; neither of them was quite ready to be married yet. It’s not that they weren’t allowed to leave the house, but random wandering around town was frowned upon for good girls, which they were. Sometimes Fatima-Zohra embroidered things that she’d try to sell later. Over the several months that I knew them, it was clear that they were quietly going crazy. Amel started having fainting spells; one day it was so bad that they rushed her to the doctor. She was on anti-anxiety medicine the rest of the time I knew her. What I mean is: time is a problem everywhere, even if it isn’t the only problem.

(b)

The phrase time management implies that time can’t be trusted, that unless kept to a tight schedule it’ll run from us like a loose dog. When, of course, what really can’t be trusted is us. Without a plan, we spend the day feeling bad about ourselves; we could do anything, or nothing, and so instead we have a panic attack.

Ben Franklin liked to look at his hours all mapped out on the page (his schedule for 5 to 8 a.m.: “Rise, wash, and address Powerful Goodness! Contrive day’s business, and take the resolute of the day; prosecute the present study, and breakfast”). With such enlightenment baggage bred into us, how could we help becoming an anxious nation, fond of our day-planners and Google Calendars?

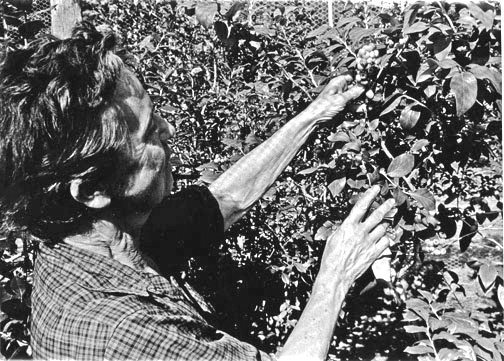

Wouldn’t it be better if we could go back to the literal meaning of productivity? We could all produce things. At the end of the day, we would each have a small pile of objects to point at with pride. We would sleep deeply and have useful dreams that we wouldn’t remember in the morning, except for the lingering sense of accomplishment they left us with. No wonder so many of us have started farming, or canning, or fermenting wine. Or, on our most helpless and indoor days, reading memoirs by people who did these things.

3.

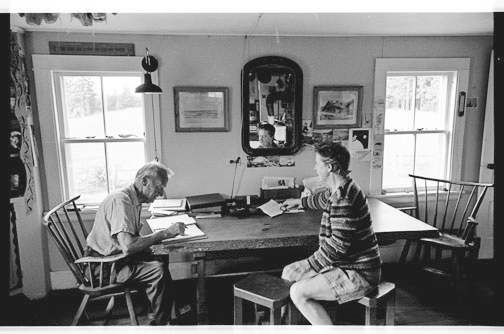

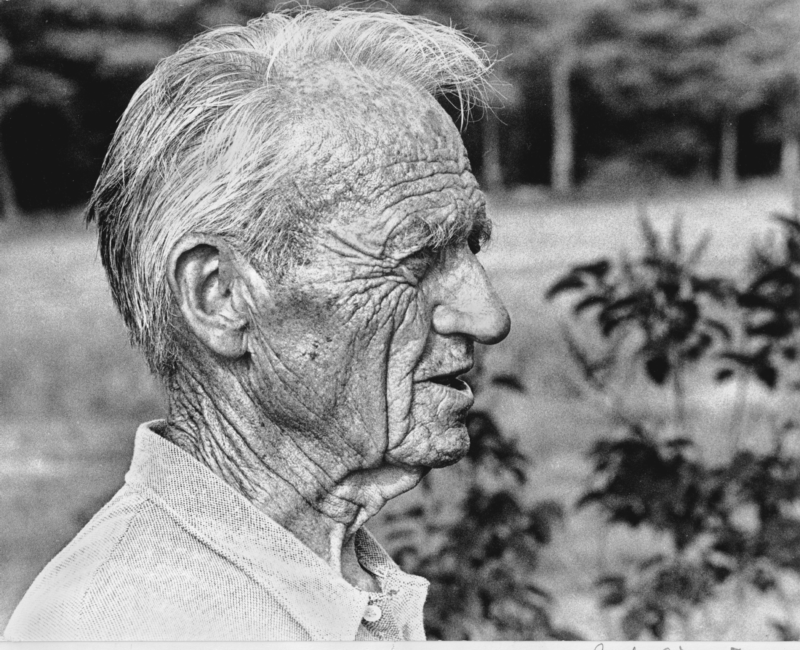

Judging from the letters Helen included in her memoir of their fifty-plus-year marriage (Loving and Leaving the Good Life), Scott Nearing could be passionate, but mostly he wasn’t. He starts his love letters with “I wish you well” and ends with “Life’s best to you always.” When he’s upset with her, he writes in outline form (“II. Certain applications of these theoretical points”).

When he and Helen met, in 1928, Scott was forty-five, divorced, so obstinately principled that he couldn’t keep a job, too extreme for the socialists, and not deferential enough for the communists. Helen was twenty-four, fresh from the Krishnamurti debacle. They drove upstate and talked about pacifism, vegetarianism, and fairies. They went for an evening walk: “The deep-woods, grassed-over road we had followed wound up a hill lined with flaming maples,” Helen writes. When they reached a crossroads, she impulsively kissed him.

Without a job that counts, without a baby, a reasonable person, or a person from the past, might try instead for a husband. Extra points for one who’s older, and didactic, and very good at chopping wood. Someone with decided opinions about what a proper day should look like. This is how a letter about the business of life becomes distinctly romantic.

To Scott Nearing, the urban, moneymaking world was “shattered, purposeless, functionless, ineffective, unworkable.” And so if you, a person in that world, ended up feeling shattered, purposeless, functionless, ineffective, and/or unworkable, that made sense. Scott encouraged Helen to become “free of Ridgewood,” both geographically and metaphorically, spurring her to leave her family home for a rented room in New York. “In order to experience life in the raw,” as she put it later, she worked at a paper mill, a box factory, and a candy-packing plant. Each week, she earned around fourteen dollars, and paid eleven dollars in rent; she survived on grapefruit, Triscuits, and chocolates that had fallen off the conveyor belt.

After that winter of labor, “Scott made the further suggestion that I might think of going back to my fancy European friends for a while to see which way of life I wanted to live, with him (the low life) or with them (the high life),” Helen wrote. Scott’s plan almost backfired. Helen wrote him that she was busy “sky-shouting” and “racing around”; instead of rationally planned days devoted to labor in the service of rectifying the world’s economic and political wrongs, she took off “for an all day sun-bath, in company with four devoted and amusing swains.” The telegram Scott sent to win her back characteristically leaves out love in favor of a higher virtue: “Enough cash granted to begin work on my book War. Will you come back and help?”

4.

It’s gray out, and someone keeps throwing handfuls of birds across the sky. In this kind of weather, people younger than me are bare-legged, but older people wear overcoats. Lately, when I plan to see my friends, we call it “a meeting,” and I write it on my Google Cal as such: “12 p.m., Caroline meeting.” Mornings, I feed my proxy-children (my cats, my sourdough starter). Some days I have the kind of work with a boss and the need to wear real-person clothes, but mostly I don’t. So during the long, blank spaces between meetings, I read the Nearings’ opinions on the best system for boiling maple syrup, on the ideal dimensional lumber for the frame of a stone house. “Pine is lighter, but expands more when it is wet. Spruce is tougher and expands less than pine.” Sentences like that can give me a full ten minutes of pleasure and vicarious purpose.

But purpose-by-proxy is a dangerous thing. Seductive, too: “Anybody can have a husband, but to few is it given to have a sage, and the combination of both is as rare as it is useful,” wrote the anonymous author of Elizabeth and Her German Garden. Helen Nearing: “To live with an older, wiser man who could answer all my questions was a continual delight; it was school and holiday all in one.” Dorothea, in Middlemarch: “The really delightful marriage must be that where your husband was a sort of father, and could teach you even Hebrew, if you wished it.”

But when you outsource the meaning and management of your own life, the price you pay is a flattening of yourself, of your contributions to the world. In the only memoir she wrote without Scott (because he was dead), Loving and Leaving the Good Life, Helen is both fun and infuriatingly self-effacing. She wanted to be remembered, she told an interviewer, “as Scott’s attachment. I enjoyed more being ‘Helen and.’ I don’t regard myself with high esteem.” These are classic female mistakes, ones we’re not supposed to make anymore. With all my unclaimed hours, I should be teaching myself Hebrew.

I don’t, of course, and the hours pass anyway. Recently, I’ve been wondering if it’s just as much of a trap to rely on yourself for all the meaning in the world, to be self-sustaining and self-improving and self-motivated and self-employed. How exhausting! A baby, a husband, a farm, a philosophy, a career, even: is it so wrong to long for something worthier than your single self?

And so, on the longest unmarked mornings, I read Scott Nearing’s best love letter, but pretend that it was written by the world instead of Helen Nearing’s brilliant, certain, overbearing husband: “I am convinced that there are several important things we must do together,” the world tells me. “Let’s inquire till we find out what they are and then let’s set about the tasks. It is such a great joy to look forward to work with you.”