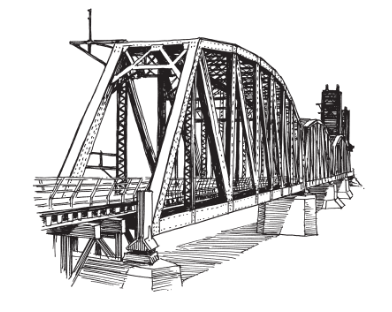

Years of commuting on the PATH train, the bland and comforting specter of a subway running between New York and northern New Jersey, have given me plenty of time to consider what cartoonist Ben Katchor calls the pleasures of urban decay. While careering toward Jersey City, the train suddenly surfaces with sonic force to an industrial landscape covered in phragmites, brown grasses that look like toxic wheat. To the left is the massive Guyon Pipe Fittings and Valves factory, an abandoned brick A-frame covered by rows of delicate glass windows, pale green and broken. Out the other window the Pulaski Skyway—a raised highway built in the twenties to shorten the trip between New York and Newark—dips off to the right where the train crosses the Turnpike bridge, a coal-black set of girders resembling an erector-set robot.

The place is so improbable, with its abandoned cranes and piers whose function was probably known only to a select few, that every visit provokes at least unconscious doubts that you’ll ever escape. The spirit behind the factories and bridges, however dismal and decrepit now, was one of a grandiose idealism. Seeing them, I can’t help but feel wonder at our force of will, what it must feel like, I’d guess, to arrive in Giza or Machu Picchu, or maybe a postwar battlefield. What kind of person could dream up such schemes and then imagine them possible? Perhaps it’s the outsized confidence of these plotters that impresses me as much as the structures themselves.

Today’s techno dreamers, though, long for the minuscule, the counterintuitive and therefore pleasurable notion that the compact is more powerful than the gargantuan. Transistors and microchips, slender fiber-optic lines: these enthrall the same sorts of minds that brazenly designed twenty-ton steamrollers and under-one-roof manufacturing operations. The absurd capabilities of an average cell phone or Palm Pilot may be wondrous, but they can’t inspire or terrify like a steel mill.

Those most passionate about the industrial landscape are the very people who have most shrunk that breathtaking scale to a low-tech whisper. They’re not building new, great monuments to industry; instead, they write papers about the history of the can opener, give walking tours of open-pit mines in Arizona and grain elevators in Buffalo, and deliver talks on powerhouses. They use terms like SHPO (pronounced ship-O)—for state historic preservation office—as in, “The building cleared Pennsylvania SHPO”—and HAER, the Historic American Engineering Record, a part of the National Park Service that documents most anything that might be considered an engineering feat, from covered bridges to power mills. They’re preservationists with a focus quite removed from the DAR-types standing guard over the relics of the white-wigged set in historic houses across the country....

You have reached your article limit

Sign up for a digital subscription and continue reading all new issues, plus our entire archives, for just $1.50/month.

Already a subscriber? Sign in