At the age of three, George Tabori, a young boy growing up in Budapest (the year is 1917), goes to the circus for the first time. Drumrolls commence. A young girl climbs onto a fifteen-meter-high platform. She takes a step back, jumps, misses both the trapeze and the safety net, and crashes onto the floor, finishing in a bloody, lifeless mess. “For several years I thought that that was part of the performance,” he wrote. “When I go to the theatre nowadays, I still expect something similar, and I am a little bit disappointing when it doesn’t happen.”

*

Sixty-three years later, in 1953, George Tabori and Alfred Hitchcock go on a trip to the American Midwest to find locations for an unnamed film project. “There are parts of the American landscape which are so strange, so surreal, you just really want to build a film around them.”

Tabori and Hitchcock come across a number of enormous crop silos, scattered across the arid plains. Tabori suggests a chase sequence that would end with one of the villains falling into one of the silos from a great height. Hitchcock is skeptical about the idea.

Next, they visit a modern, automated abattoir. Cattle enter the slaughterhouse on an assembly line on one side and exit the factory at the other, the animal processed and packaged into tins. Tabori suggests a shot showing one of the villains falling into the abattoir from a great height—the next would show a pair of eyes rolling on the conveyor belt at the end of the assembly line. Hitchcock doesn’t like this idea either. Soon after, he calls off his collaboration with Tabori.

*

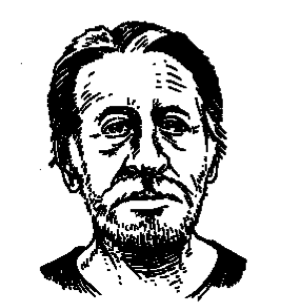

The first half of George Tabori’s career was remarkable only for the consistently negative outcome of his artistic endeavors. Born in 1914 in Budapest, Tabori moved to London at the age of twenty-two, where he worked for the Secret Service and the BBC. He wrote four novels: Beneath the Stone the Scorpion, Companions of the Left Hand, Original Sin, and The Caravan Passes, all extremely ambitious historical novels which were marketed incongruously as spy thrillers. None of them were particularly successful.

From 1947 until 1969, George Tabori worked as a scriptwriter in Hollywood and New York, where he mingled with the rich and famous. He joked with Charlie Chaplin, smoked with Thomas Mann, canoodled with Greta Garbo, and talked literature with Marilyn Monroe. When one of his plays, Flight into Egypt (1952), finally appeared on Broadway, it was directed by the legendary Elia Kazan, who had made Tennessee Williams famous with productions of A Streetcar Named Desire and ...

You have reached your article limit

Sign up for a digital subscription and continue reading all new issues, plus our entire archives, for just $1.50/month.

Already a subscriber? Sign in