Note: This guide is intended to help provoke thought and to generate discussion in your reading group. You are encouraged to use the following questions to stimulate lively conversation, to increase your enjoyment and appreciation of McInerney’s novel, and just generally to understand or face up to your incipient and aching awareness of lost youth.

1.

Well God, has it really been twenty years?

2.

Did you see the movie Bright Lights, Big City before you read the book? And seated in non-stadium seating in that small-town theater in Virginia beside the first girl you ever had sex with, did it seem like New York City just might as well have been on another continent? Didn’t some of your high school classmates suffer terrible hunting and farming injuries each year? And was your sense of Beauty so unrefined that you thought the movie was “pretty cool”? Didn’t you have a flat-top? And did you get the suspicion, years later, that you were not the first person your date for the movie had had sex with, her assurances to the contrary notwithstanding?

3.

And then did you read the novel for the first time in college, which did not have a dining club and was far too close to the small town you grew up in? And what was your response? Wasn’t your response that though it did seem “better than the movie,” it still seemed so exotic in setting and action as to seem almost unintelligible? Hadn’t Nancy Reagan sort of convinced you that if you tried cocaine, or really even glanced at it or got inside the same room with it, that you would immediately die? Remember Len Bias?

4.

And remember the hip young professor who taught the novel in a contemporary American literature course at the agriculture and engineering university where you went to discover art? Remember how he brought in a ghetto-blaster and played the Talking Heads song that is mentioned in the book and how then you went out and bought a Talking Heads cassette tape in an independent, non-chain record store with unwashed clerks who looked a lot like your professor and were just crazy about Dinosaur Jr.? And smoked cigarettes during class, this professor did, remember? And how he explained the whole novel in terms of a surface/depth matrix that implicated our superficial times? And how McInerney’s use of the second person, which, as you know now but did not then, a writer should really never use, works in Bright Lights because it is actually a disguised first person? And how the point of view reinforces theme and character because the nameless protagonist can’t face his own life, can’t claim his own story, and so must deflect and deny with the superficial you? As in the opening sentence, “You are not the kind of guy who would be at a place like this at this time of the morning”? How there is actually a double denial at work here, the explicit denial (“You are not the kind of guy…”) and a denial implied by the second person point of view? How the self is obliterated? How the protagonist uses second person in much the same way he uses drugs and booze—as a way to get out of and away from himself? And maybe this all seems so obvious now, but remember how you were sitting there in your desk in the crappy English building in the middle of a giant Ag school, having never before considered the rhetorical implications of point of view (or of anything else for that matter)? And weren’t you at that point a communications major with a hairstyle that teetered on the brink of mullet? And wasn’t this just a big world opening up, the system of literature? And remember how you went to see that hip young professor a year later to tell him you were now an English major, and thanks, and he was cleaning out his office because he didn’t get tenure?

5.

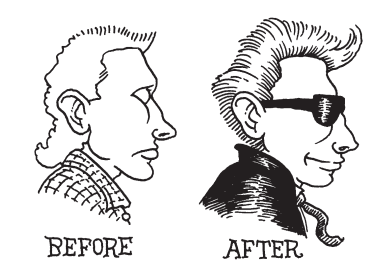

And now do you have that same edition that you bought used and read in college? Who has that edition? Hold them up so everyone can see. And can you still see the price ($2.00) written in pencil on the inside flap? And the second page is ripped, but you can still see the picture of the dazzling young author, looking invincible? And actually, didn’t your hair actually kind of look like his, except maybe a little more rural? And as you flip through the book do you see that someone before you—it could not have been you—underlined certain passages, a lot of passages early in the book, but then fewer and fewer as the book goes on, and even wrote Ha! and anti-quest in the margins, in handwriting that was clear, optimistic, and certainly not your own?

6.

And how many times must you have packed this novel in cardboard boxes that you got outside of Kinko’s or the liquor store, preparing to drive away, in an Omni or a Reliant, from one woman/job/graduate program toward some other, more promising woman/ job/graduate program? In how many apartments and how many U.S. states have you packed and unpacked this old Vintage Contemporaries edition with the almost cartoon-like cover art they once used for their entire catalogue? What were they thinking? Seriously:What were they thinking? Do you know the edition being discussed currently? It’s those gaudy Vintage covers that look like the bad graphics of a bad video game? And isn’t this just a great example of how while literature might aim to be timeless, its packaging seeks to be of the moment, and so you often see, in used bookstores, these great old novels that still speak to us beneath covers that are as ridiculous and dated as the architecture of the buildings on campuses of state universities that house English departments? And doesn’t this cover illustrate just perfectly,if unintentionally, the surface/depth matrix? Isn’t it fitting that a book whose whole point is basically that gaudy appearances are misleading has a misleadingly gaudy appearance? Is it possible that this dumb and superficial cover is part and parcel of the novel’s critique of a dumb and superficial culture that masks and numbs the underlying pain and loneliness? How generous are you feeling? Anyway, and the Vintage cover of Bright Lights shows a young video-gamish man from behind (the nameless protagonist? McInerney himself?), wearing a black leather jacket with a wrap-around belt (like a robe) and with the collar, of course, turned up? And there is a street light and part of a neon sign from the Odeon club? And two tall skyscrapers rise into the night? And if those two skyscrapers aren’t the twin towers,don’t they, for us, standing as we are on the opposite bank of a historical Rubicon, unfailingly evoke the twin towers and thereby sort of make the novel seem older and quainter than it is—like it comes from a simpler time, back when NYC was quaintly and simply overrun with yuppies, drugs, rats,the homeless,pornography,violent crime, and Darryl Strawberry?

7.

Sorry, there’s no Bolivian cocaine, but would you care for some more chips or low-carbohydrate beer?

8.

And sweet Jesus, would you look at the blurbs on the front and back of this edition? Carver, McGuane, Plimpton, Hannah, and, once you peel back the used stickers that never seem to peel back easily and you end up having to scrape them off but the spot remains sticky, Wolff? Holy shit? Where’s Salinger? Even if you understand the venal world of big-time publishing and the politics of blurbing, that’s still an impressive jury, rigged or not, isn’t it? And remember that great little nugget in Jonathan Franzen’s essay on William Gaddis about how Gaddis didn’t care for Pynchon or other abstruse coevals, but he got a big kick out of Bright Lights, Big City? Isn’t it fun to think of Gaddis, in a smoking jacket, chuckling about ferret pranks? But are you aware that the reviews of the novel, especially in New York, were mostly bad? That Michiko Kakutani, instead of just ignoring a young novelist’s first novel that she didn’t care for, trashed it? Doesn’t that seem unsporting? Even if the young, brash, club-hopping McInerney may have made himself a target by being so blatantly overexposed upon the publication of his hip novel that even you heard about him in your small town in Virginia?

9.

The same Michiko Kakutani (who else?) who just trashed David Foster Wallace’s new book of stories, Oblivion? You are tempted to say she ripped Wallace a new one, but would that be anatomically incorrect since she has previously ripped him a new one? Perhaps she ripped (re-ripped?) him an old one? Are you the only one in this reading group who thinks that the level of her animosity toward Wallace’s work seems sort of hysterical, ad hominem, and way out of balance? As if his book of stories, rather than just being bad or not at all to her taste, actually did something unforgivably mean to her or her family and she is seeking revenge? As if his book got drunk and drove its sports car right over her pet, and then took off? Do you realize she called one of his stories—a very good one, you think— “sophomoric,”“morally repugnant,” and “sick”? Granted, your personal opinion is that a massive and extraordinary talent like his [=Wallace’s] should be cherished and applauded and nurtured and garlanded with garlands, but even if one does not care for his writing, what’s with the venom? Why so cruel and vitriolic? You mean it: Why? Why take it as a personal offense what Wallace is, as Kakutani believes (wrongly, you would say), squandering his considerable abilities? Please don’t smoke in here? Well and just to complete the circuit, did you know that McInerney reviewed Wallace’s Infinite Jest for the New York Times Book Review in 1996? Would you please take a copy and pass it on? And in this review, as you can see, McInerney calls the novel “alternately tedious and effulgent”? And even though McInerney’s review is hardly glowing (mixed at best) and that at one point he says that readers, halfway through the large book, may be tempted to shoot Wallace or themselves (i.e., with a firearm), it still doesn’t feel, you know, at all personal or vengeful?

10.

What do you make of the Hemingway epigraph in Bright Lights? Isn’t it sort of like having an alligator on your shirt back in middle school? Or is it employed to suggest that the novel has a certain depth beneath its glittery surface? Who knew Hemingway could be funny? Wasn’t the epigraph to The Sun Also Rises that Stein quip about the lost generation? Couldn’t that line pretty much be the epigraph to Bright Lights, as well? Actually, now that your thought is provoked on this matter, couldn’t that Stein quote be the epigraph for every American novel published in the last seven decades?

11.

Rereading the novel—be honest, now—didn’t you enjoy it? Even more than you did in the eighties? Isn’t it energetic? Fundamentally humane? Weren’t you sort of surprised, rereading it, at the extent to which you did not dislike it? Because it’s good? And not good in a hokie, retro, campy way, either, but really pretty good? Did you open your jaded heart to it? Did you? Did you find it not just well-written and funny but fairly powerful, reading it now, and just shot through with a sadness that is difficult, but not impossible, to analyze? Didn’t the book transcend its membership in the risible sub-genre of hip, urban eighties novels and affect you in a strong and unforeseen way that would be utterly mysterious and inexpressible but for these stimulating and provoking questions?

12.

And yes, the sunglasses-for-bread swap at the end of the novel is symbolically heavy, to put it mildly, but so what? Would you please just go with it? Can we not be so cynical? Can we establish a wink-free zone? Because, listen, how many young, cheeky writers today would have the guts to write that scene? A scene that indicates, however heavily or sentimentally, a turn toward something real and substantial and spiritually nourishing, and a turn away from the culturally available modes of being? Or is it not even a matter of guts? Might it be that the evasive, ironic, superficial style that McInerney intended to portray as a specific coping mechanism, as a response to personal tragedy and disappointment has, since the novel’s publication, become the general and unquestioned style of the day? The implication being, God, that it’s difficult, or that it might be impossible, to turn away from a style when you cannot even conceive of a different style? What, the implication being that if glibness is a general and culturally instilled condition,a way of being in the world that it is not causally linked to anything specific and tragic, then it’s much more difficult to confront and rebuke? Because it doesn’t seem to have an origin that can be faced up to? Can we, twenty years on,even comprehend or translate the Ray-Ban-for-hard-rolls exchange at the end of the novel? Is there an issue of incommensurability here?

13.

Why is it that if you were among literate-type people at a party and the subject of this book came up, why is it that if someone—someone perhaps who had had a fair number of highballs already—if someone expressed an admiration for Bright Lights, why is it that that expression would feel like a dirty secret or an admission of a guilty pleasure? Why would they have to say, “I like that book,” or,“I actually like that book,” with the qualifier and the italicized like, to indicate that liking it amounts to taking a stand?

14.

Is it that patina of eighties cool that is difficult to rub off, to see through? Is it because the novel must to some extent partake—stylistically, formally, thematically—in some of the garish indulgence and excess of the eighties in order to critique it, and thus seems dated in a way that, say, White Noise (1986) or The Mysteries of Pittsburgh (1988) do not? And didn’t you, by the way, learn that word patina from a Donald Barthelme essay, in which he states, so nicely, that “words have halos, patinas, overhangs, echoes.” And might we say that novels, too, have halos, patinas, overhangs, and echoes? And doesn’t this novel have a particularly long and extended overhang, under which we have stashed Max Headroom and Don Johnson and legwarmers and that vampire movie with Kiefer Sutherland and also Bret Easton Ellis?

15.

And Reagan, for that matter? Doesn’t Ronald Reagan, who recently died, sort of strangely loom in this novel without ever being mentioned explicitly? Is this just because he just died? Or is it because McInerney said in some interview somewhere that he thought Bright Lights advanced a modest critique of a country that has, for its president, an actor? Or is it because it’s just impossible not to think of the selfish, sybaritic eighties without thinking of Reagan?

16.

Can you make a beer run? Shit, is it Sunday? Can you believe that you own a house, that you’ve settled into the suburbs of a military town where you can’t buy alcohol on Sundays? Where reading groups flourish? Where your lawn is patchy and you care? Where the crystal meth labs occasionally explode, rattling your double-paned windows? Would you say you have gotten older in two ways? Gradually and then suddenly? You got one of those computerized sprinkler systems?

17.

And like nearly everyone else in America you have an MFA in writing so you know that writers of literary fiction are not supposed to keep secrets from readers—it’s not fair play—but isn’t McInerney’s protagonist’s secret (his mother’s sickness and death one year before the action of the novel, or what we call the fictional present) justified, literarily? Isn’t it, in the capitalistic argot of the workshop, earned? Aren’t denial and avoidance in effect the structural principles of the novel? Didn’t your wife liken the formal strategy of most of the novels you read to two guys sitting on a couch watching sports, the idea being that the rhetorical situation is not really engineered to foster truth, insight, or communication, that it is in fact engineered to avoid and deny these things, but such that any confrontation of anything real will be oblique, glancing, incidental, but perhaps for that very reason all the more powerful? So that while the protagonist attempts to skim across the surface of his life—anesthetizing himself with drugs and booze—he is unable ultimately to outrun his grief, his family, his failures, his sense of unmet promise? That sounds corny, doesn’t it? So isn’t it as if there is a black hole at the back of this novel, big gravity, pulling everything toward it? Is it true that sharks must keep swimming or they die? And besides, now that you have reread it, can’t you see all the little hints about the mother throughout? And the book’s basic obsession with mothers and babies? Do you want page numbers?

18.

Do you hate the novel’s puns and wordplay (dawn’s surly light, womb with a view, all messed up and no place to go, in medias dress, etc.)? Do readers ever enjoy word-play as much as writers? Can you justify it in the sense that wordplay draws attention to the surface of language, and thus it is a rhetorical strategy that is intimately connected to the novel’s—no? Too much of a reach? If we don’t find it pleasurable or pertinent,can we at least regard it as the play of a giddy young writer who is reveling in the possibilities of language? Isn’t there something youthful about the wordplay? Even endearing? Are you stretching or do you have something to say?

19.

And while no doubt the novel feels dated,with its references to the Kremlin, Ray-Bans, and ghetto-blasters, doesn’t it in some ways feel remarkably contemporary? Doesn’t its use of present tense, for instance, seem to predict the next twenty years of American fiction? Doesn’t it seem like present tense is the default tense for edgy U.S. prose these days? What better way to suggest the cruel and overwhelming pace of culture—a culture that renders reflection or introspection impossible or at least undesirable? George Saunders? And also the short chapters? And also the pulsing pain beneath the manic, comic style, as in Mary Robison’s recent novel, Why Did I Ever, which we should really read for next month? And doesn’t the crippling self-consciousness, the sense of regarding oneself as an actor in a movie, and the loneliness and the mania about fraudulence and legitimacy seem to be just what a lot of people, including Wallace, are currently writing about? And the search for some form of authenticity? And that enormous, yawning chasm between the self and the culturally available representations of the self? And OK fine, even if you accept the basic philosophical point that the self is always a representation, can you agree that there are better and worse,less harmful and more harmful, healthy and unhealthy representations? Don’t the sadness and loneliness and disillusionment of Bright Lights feel of the moment, if we can just get past thinking of the movie Less Than Zero with Andrew McCarthy, which we have also shoved beneath the overhang besidethe original MTV VJs?

20.

And, coming right down to it, are there not other levels of sadness here besides the sad story of a twenty-four-year-old character who has already lost a parent and been divorced and who is realizing that the optimism and expectations of his youth were wrong and now painful? In reading that the lonely protagonist dreams of a “Brotherhood of Unfulfilled Early Promise,” isn’t it difficult not to think of McInerney, who by any reasonable standard has had a very fine and enviable career but who is nevertheless regarded by many as not living up to the promise of Bright Lights? (Isn’t it worth noting here that the two prevailing attitudes about this novel—1) it’s cheesy,and 2) it represents its author’s unfulfilled early promise—are non-complementary and mutually exclusive? Isn’t that like saying that the book sucks and McInerney was never able to suck quite like that again? What’s with that?) And shifting from the author to the reader, to you, doesn’t the novel leave you with a stupid, romantic nostalgia about lost youth even as it reveals the stupid romanticism of youth? Is this a paradox? That the novel simultaneously dramatizes the ignorant, arrogant idealism of the young, and also makes you wistful about it? Is it a nostalgia for at least having romantic notions to lose? You can’t help it, can you? Would you turn to page 9?

On Bleecker Street you catch the scent of the Italian bakery. You stand at the corner of Bleecker and Cornelia and gaze at the windows on the fourth floor of a tenement. Behind those windows is the apartment you shared with Amanda when you first came to New York. It was small and dark, but you liked the imperfectly patched pressed-tin ceiling, the claw-footed bath in the kitchen, the windows that didn’t quite fit the frames.You were just starting out. You had the rent covered, you had your favorite restaurant on MacDougal where the waitresses knew your names and you could bring your own bottle of wine. Every morning you woke to the smell of bread from the bakery downstairs.You would go out to buy the paper and maybe pick up a couple of croissants while Amanda made the coffee. This was two years ago, before you got married.”

Well and doesn’t the protagonist seem ambivalent here as he stares not at the apartment, but at its windows, recalling the life behind them with a woman who, just two years later, is his ex-wife? Like on one hand showing how young and stupid and naïve he had been, and how he was living according to some idea of himself, loving this idea as much as, or instead of, the life itself ? And that of course this whole fantasy world had crumbled, how could it not crumble? But on the other hand seemingly wistful for this unrealistic fantasy life? And even though you know from the novel, not to mention your own life, being nearly ten years older than the protagonist,that the dream doesn’t hold up, why is the dream still so poignant? Why does it create that dull ache? It does create a dull ache,doesn’t it? Is it the claw-footed bath in the kitchen? Is it that you realize that you are unlikely, given the conditions of your life (which are, let’s be clear, very nice conditions), to move to New York City and rent a small, dark, tin-ceilinged apartment near a bakery? Well and because, among other things, you lack the absurd youthful romance to try such a thing? Here in this novel the protagonist goes to great lengths to illustrate the pain of inevitable disillusionment, and yet you are struck by the beauty of the illusions? What is wrong with you? Are you sad because the romance is ultimately dangerous and false or are you sad because it becomes increasingly difficult to sustain the dangerous and false romance? How American, how middle class can you get?

21.

And there’s this (p. 127): “You considered violence and you considered reconciliation. But what you are left with is a premonition of the way your life will fade behind you, like a book you have read too quickly, leaving a dwindling trail of images and emotions, until all you can remember is a name.” So OK, well, any final thoughts about the dwindling trail of images and emotions? No? Fading life? Metaphor? You taking off? Is it that late?

22.

You OK to drive?