I. Yellow Roses May Be All He Can Bring You.

Sometime back in 1970, four newly signed musicians decamped to the middle of the English countryside and proceeded to record their first album al fresco. If you ever take a train between Oxford and London (change at Didcot), blink and you might easily miss the place where it happened. The village of Appleford amounts to little more than a signpost surrounded by farmland, with a crumbling church tower barely visible beyond. There are no blue plaques designating the site as in any way extraordinary. Yet, if you do manage to catch a glimpse of the place as it whips past the windows of a Virgin express train, you should tell yourself that this was where, some forty years ago, British pop music took a deep breath between its psychedelic comedown and the arrival of stadium rock. This was the locus of a short-lived strain of acoustic music of almost avant-garde vulnerability and gentleness—the equivalent of what Erik Satie might have sounded like to throngs of Beethoven fans and Wagner nuts. Out in the middle of that field is where autumnal folk had its definitive moment. That it drifted away as quietly as it came is perhaps part of its appeal and enduring mystique.

There he stands on the farm

With his eyes on the windmill

And his head goes round and round

Like the hours of the night will

The album begins with a song called “Yellow Roses.” Over the sultry hush of the countryside, a piano begins by caressing a simple music-box melody—nostalgic and heartrending all at once. A guitar and then a mandolin follow suit, their harp-like arpeggios slowly building. Then the voice: not streamlined or affected, but a frail human voice, almost sighing the bittersweet tune. The chorus comes, the song opens up. A two-part harmony wafts in like tumbling leaves before a third voice, equally vulnerable, takes up the next verse. And you realize this is one hell of a radical way to begin an album amid the musical landscape of 1970, even for a folk-rock band. This is the sound of the dawn breaking, intermittent birdsong and all.

Put plainly, “Yellow Roses” is one of the most impressive British folk songs of the era. Its unpolished, pastoral beauty is astounding, its vocal harmonies all the more moving for being faintly imperfect. It’s as if Alan Lomax had wandered into an English village and happened upon a band of locals as fluent in Paul McCartney as they were in evensong. The track can even be said to share some of that melancholy grandeur present in landmark songs like “Catch the Wind” and “Who Knows Where the Time Goes?” Yet it remains largely unknown, unheard, uncelebrated.

The band was called Heron. It consisted of four young men from Maidenhead, in the south of England, the lineup having coalesced around the Dolphin Folk Club in their hometown. Founding member Roy Apps and fellow traveler Gerald G. T. Moore made up the two principals, both handling guitar and vocal duties. They also had a Garfunkel-like sideman in the curiously named Tony Pook to fill out their harmonies and occasionally take lead vocals himself. Yet like the Incredible String Band before them, Heron decided to forgo the obligatory rock-and-roll rhythm section.1 This meant no throbbing bass and no drum kits. The sole embellishment Heron required was eventually found in Steve Jones’s minimalist accordion and piano playing.

This was plainly not your typical folk-rock outfit. Fairport Convention may not have been shaking in their amped-up boots, but Heron’s swapping of backbeat for quiet folk tapestries was their masterstroke. Though it sustained itself for just one of their two albums, this style unites them with a similar group of musical reactionaries (Nick Drake, Vashti Bunyan) all but ignored in the early ’70s, all of them linked by a thoroughly shy, thoroughly autumnal sound.

Heron’s first break came when Roy Apps was signed to a music publishing contract with Gus Dudgeon, who had already ushered the Zombies and David Bowie onto the charts (and was about to do the same for a young Elton John). Shortly thereafter, the band landed a deal with Pye Records on its fledgling Dawn imprint. Although Dawn housed a rather uninspiring roster of “progressive” acts—its most prominent offering was Mungo Jerry—things continued to look promising for Heron. Their contract had been secured by Pete Eden, the man who had first recorded and made a star out of the pre-psychedelic Donovan, and it was Eden who wanted to produce the Heron album. Not only that, but the band now found itself falling in with some seriously well-connected movers and shakers: John Peel, David Bowie, John Martyn, Al Stewart, Ralph McTell.

Initial toe-testing in the studio fell flat, however. The band was out of its element. All the musicians were convinced that, in order to capture the special sound they had honed in intimate club gigs, the recording would have to be more organic, more spontaneous. It was therefore suggested that they hire out Pye’s mobile studio (basically a van with a mixing desk), go on a field trip, and cut the album outdoors. It might have been a gimmick, but the band would be staying true to the pastoral qualities of the music, and to Roy Apps’s songwriting in particular. One need only turn to the lyrics in songs like “Upon Reflection” to see the logic in the band going rural:

We walked across the fields of Berkshire

Resting in the hay

And making daisy chains

Out along the streams and rivers, spread across the way

And swelled with recent rain

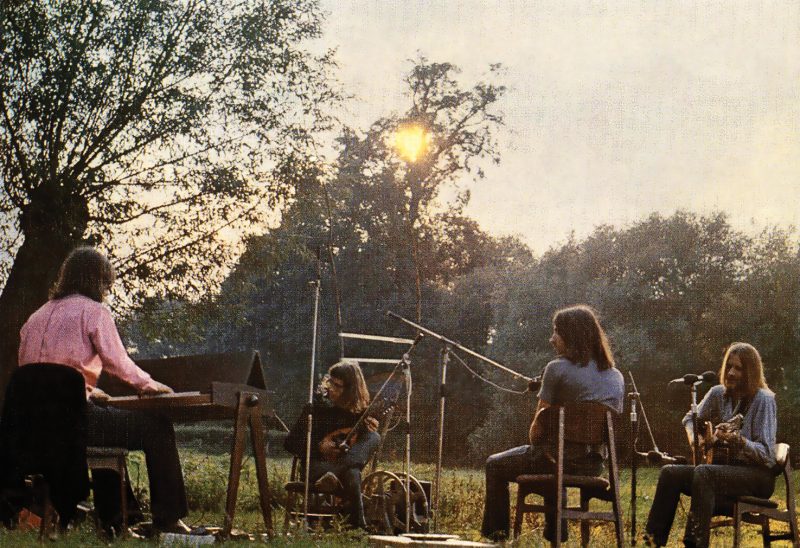

The back cover of that first, self-titled album shows the members of Heron recording a song somewhere in that field in Appleford. The four of them are sitting as if around a campfire, surrounded by their sparse equipment. Just a handful of well-padded microphones, four matching chairs (which seem to have been borrowed from someone’s kitchen set), cables on the ground, a dusky light in the trees. There isn’t an amp in sight; the instruments have all been individually mic’d. As befits a field recording, they are cutting the track live, in unison. Apps is at the far right on guitar, Moore on mandolin, while a pink-shirted Steve Jones mans a small portable piano. Tony Pook sits without an instrument, with his hands in his lap and his back to the camera like a one-man audience.

There is, however, one more instrument, though it’s not immediately apparent until after you have put needle to vinyl, or slipped the reissue CD into its compartment. Yes, that last ghostly addition to Heron’s sound—it’s literally there in the gold-tinged haze, in the grassy meadow at the band’s feet. You hear it soloing at length in the pauses between each track: not analog silence, but the hum of the open air.

Interlude: A Thumbnail History of Autumnal Folk

That sound Heron was after is crucial to the story, but it needs some qualifying. The roots of this group, like those of any folk-based English band, go back to the great British folk revival spearheaded by figures like Ewan MacColl and A. L. Lloyd in the early ’60s. However, any relation to the finger-in-the-ear purists is, thereafter, a tenuous and troubled one. Instead of restricting themselves to traditional song forms, the exponents of what would later become autumnal folk chose to beat a distinctive path. From the start, this peculiar strain was bohemian, downbeat, and introspective. It was also openly transatlantic.2

The first real touchstone was the bluesy folk fusions of British troubadours like Bert Jansch, who recorded his seminal first album, unaccompanied, on a reel-to-reel in a friend’s kitchen. The early Donovan, along with expat singer-songwriters like Jackson C. Frank and Paul Simon, also had a role to play in keeping the music both introspective and earnest. But it was the influence of the Incredible String Band in the mid-’60s that left the most lasting impression: the ISB’s epic stew of whimsy, world music, blues, and bluegrass, which superseded even Bob Dylan in breaking open the folk idiom for subsequent autumnal-folk performers. Tracks like “October Song,” “Chinese White,” and “The First Girl I Loved” helped expand musical horizons while offering a whole new rubric for a reflective, acoustic intensity. Not the aggressive, overtly sexual intensity of rock and roll, but something more sensitive.

The key was that autumnal-folk artists remained true to their acoustic heritage while still absorbing the influence of ’60s pop. The unadorned, cool sobriety of Jansch’s early albums had fixed the autumnal ambience sturdily into place, and this kept the psychedelia at bay. Indeed, what sets these artists apart—aside from their somberness—is how un-stoned their music actually sounds in spite of its having been recorded at the fag-end of the ’60s. Regardless of the hippie leanings that autumnal-folk artists shared, their music still sounds remarkably focused to this day.3 Theirs is a style striving not to be far out but always right here, as intimate and as vulnerable as possible.

So, you may ask, what makes music like this essentially autumnal and essentially folk? First of all, that you can discern the earthy roots of the British Isles, at least an underlayer of traditional song. Second, that it is also relatively pop-oriented, preferably with lyrics of a pastoral nature. Third, that its melodicism tends toward mezzo-piano melancholy, that its mood is ephemeral at heart. Last, that it does all this in a staunchly acoustic, low-key format, with as little elaboration as possible. No belting to the rafters, no drum solos.4

This is partly why catch-all terms like folk rock and more anorak-flagging ones like psych folk fail to pin down the autumnal sound. Historically, there is no tie-in fad or craze to ascribe to this sudden and short-lived blossoming of folk-pop melancholy (except of course a far more general, post-’68 cultural hangover). This was never an organized movement, but more a moment spied in hazy half glimpses—in the startling calm of John Martyn’s early albums, for instance, or on Bridget St. John’s Ask Me No Questions, in the leaf-rustling atmosphere of songs by the now unjustly forgotten Dando Shaft or in the quieter parts of Van Morrison’s Astral Weeks (1968).

But let us take two of the preeminent names in what I’ve been describing as autumnal folk: Nick Drake and Vashti Bunyan. Both were produced by the legendary Joe Boyd (already a producer/manager for the Incredible String Band and Fairport Convention). However, their collective output was met with near-total indifference by the buying public of the day. Both favored acoustic instrumentation and a minimum of pop-rock ornamentation. Both also displayed a vocal restraint that would have been unimaginable without the unaffected airiness employed by earlier traditional folk singers like Shirley Collins. Yet they also shared eclectic musical tastes. One of the delights and revelations of the recent Family Tree (2007), an anthology of Drake’s early home recordings, is hearing him still in bluesy Bert Jansch mode or covering Jackson C. Frank.5 Such nascently autumnal material uncovers the influences that Drake’s genius would transcend by the time he recorded his debut, Five Leaves Left (1969). Bunyan herself, when asked how best to describe the style of Just Another Diamond Day (1970), remarked:

I wrote and sang pop songs through the mid-’60s, and only became interested in folk music for the simplicity and beauty of the tunes. I did not align myself at all with the traditional folk musicians of the time—I avoided folk clubs, for instance. I have never thought of myself as a “folksinger.” When it came to trying to explain the folk of Diamond Day to people, I thought “hippie-folk” described it better, or maybe pastoral pop….

Bunyan and Drake were too musically promiscuous and too introspective to be entirely folk, yet their music is too subdued to be considered straightforward pop, either. Neither was out to get the kids onto the dance floor. What made the music notable in the first place was its eeriness and its essential lack of showiness. One infamous review of Drake’s second album, Bryter Layter (1970), called it “an awkward mixture of folk and cocktail jazz”—which of course misrepresents completely the intricacy, artistry, and emotional depth of Drake’s music—but it does allude to the level of understatement inherent in the autumnal sound. Try looking for a guitar solo on one of these records and you will be missing the soft-spoken point. Quietly meditative may well have been autumnal folk’s fundamental mode.

That Drake and Bunyan both effectively disappeared from view before the mid-’70s may seem coincidental were it not for the fact that the music itself reflects this same gossamer fragility.6 This is precisely the autumnal quality of the music being played. Autumnal folk embodies that brisk, shivery moment when you step outside and, for the first time in a year, sense an enlivening chill in the air. Transition, upheaval, in quiet cinematic flourishes. Windswept scarf-weather and moody afternoon light. You can suddenly see your breath. You’re maybe moving house unexpectedly and there’s the smell of packing tape on your fingers. All around you, everything crisp and raw and bright. Just Another Diamond Day. Five Leaves Left.

II. The Lonely Ballad of Roy Apps

Breath on breath of morning wind

Stirs the curtain laces

You may go to chase the sun

Or vanish in its changes

I will stay to gaze upon

The sweetly smiling ladies

Yes, I will be turning back my pages

Almost every song that Roy Apps penned for Heron is shaded with this sense of leave-taking. Even with the birdsong backing it up, the overwhelming tone is one of separation and of preemptive nostalgia. The word good-bye recurs throughout that first album (even making the title of one of G. T. Moore’s contributions). There is also a hint that the emotions being expressed by Apps—in the singing, in the playing—are not themselves resilient enough to endure. The tears are welling up, glinting in the eyes of each song.

The record’s production reflects the bittersweet mood. Take Apps’s “Smiling Ladies.” Just before he and Moore finish singing the opening verses together, they take a breath in unison, and the recording is so intimate that we hear it, like a blade of shyness slicing through the song.7 Incidentals like this—birdsong, breaths, those breezy sounds of an anonymous patch of countryside—all blend into the fabric of the music itself. We too are in that field, sharing its knockout solitude, its dreamy loneliness.

Though Heron was a fairly democratic entity at this point, Roy Apps does give the impression of being the band’s real star, its first cause and organizing principle: founding member (along with Tony Pook), primary songwriter, vocalist. His songs also stand out from the rest. After “Yellow Roses,” “Upon Reflection” is the real case in point, building from a deceptively simple guitar figure that unravels and unravels, becoming as much a narrative as the story described by the lyrics. The story, here, is green with unrequited love and lush with rain-dappled imagery: a young man’s ramble through the countryside, pining alongside a detached lady-friend. We find them, at the song’s opening, “sitting in [her] mother’s garden, smoking Lebanese / Beneath the privet hedge.” The overall effect is at once naive and masterful (likewise on the sublime outtake “Rosalin,” which sounds like Robin Williamson by way of Donovan by way of Simon and Garfunkel).8 It’s a relaxed, delicate sound that would not seem out of place on a Kings of Convenience or Belle and Sebastian album: wispy, whispering, wistful.

Apps’s “Little Angel,” too, is full of somber details, quaint lyrics about bidding farewell to an impossible love affair, riding through storms, all of it underpinned by Steve Jones’s soulful organ. By the time G. T. Moore begins plucking on his muted strings during the bridge—so up-front in the mix it sounds like a pulse trembling—the song enters a whole new echelon of aching atmospherics: “The leaves have been dying / For nine months or more.… Good night little angel / I’m just going / So if you see me waving you good-bye / Good-bye…” Hearing these lines again, I can’t help but imagine the sun setting on that field where Heron were playing. It seems almost as if they had an inkling they would not be returning to this place.

Roy Apps now lives in the village of Pangbourne, near Reading, only fifteen miles from Appleford. He appears in the Cross Keys Pub, where we have agreed to meet, stooping through the doorway. Big but not imposing, he is shorn of the curtains of blond hair that made him so conspicuous on the two Heron album covers. He looks like a farmer, albeit a farmer who wears reading glasses and probably makes a habit of memorizing the odd line of Yeats before bed. As the weather is unusually warm for late February, he suggests that we have our meeting over a cup of tea in his back garden. It is only as we cross the street, however, that he tells me he has forgotten his house keys, and how we should now hope he hasn’t forgotten to leave his front door unlocked, too. Once we arrive, Apps tests his doorknob and gives a shrug. He disappears around the back, telling me to wait. Meanwhile, I’m left outside what looks to be a historically significant row of cottages. The streets are empty; it is a Sunday and Pangbourne is listless and empty. I find myself listening to the birds, wondering if Apps will show up again, or if he’s simply decided against the tea—but then his door eases open. He appears magically, apologizing, and greets me as if we are again meeting for the first time, a hyperactive spaniel pup now dancing around his feet.

Later, we sit at a weathered picnic table, and he explains what happened in between the two Heron albums. Smoking the first in a long line of cigarettes, he tells me why Heron recorded a batch of new songs rather than cherry-picking a single—like “Yellow Roses” or the languid “Lord and Master”—from their Appleford sessions. The band had decided, he says, that the album existed very much as a whole and they didn’t want to see it broken apart. Hoping for a radio-friendly single, they relied upon one of their earlier studio recordings, a cover of an obscure Dylan number titled “Only a Hobo” that they judged to be their showpiece.9

However, the band seemed already to be expanding upon the autumnal sound it had minted on the debut. A fuller, rock-oriented format was shunting the spare intimacy of the first album. The group padded out the remainder of their 1971 maxi-single release with four more rather slight tracks, all of which prominently featured bass and drums and the odd electric guitar. A ballad titled “I’m Ready to Leave” could have made a strong contender for the first album, but it gets spoiled here by an unbearably funky session drummer and a band now trying to find a groove that just isn’t there. I wasn’t about to tell Apps I felt this way—the words autumnal folk did not even cross my lips—but you can hear how his songwriting was already being shoved into the background.

Heron’s next and final release was a twofer double-LP with the shockingly unimaginative title of Twice as Nice and Half the Price (1972). Again, the band recorded outside, only this time in Devon with an assortment of session men and friends. Everyone involved is again pictured on the back cover (including producer Pete Eden, holding a toddler), though the feel this time is less atmospheric, less communal. For some reason, as I speak to Apps in his backyard, I can’t stop thinking of that red sleeveless jumper he is sporting in the photo.

It should have been a single album, Apps explains. They should have taken more time to craft the songs in live settings—testing what worked and what didn’t, much as they had for the first album—but they were impatient to get something noticeable on the shelves while the record company was still showing an interest in them. He tells me Twice as Nice was too off the cuff, too rushed.

This being the case, I ask him why, when the first album had plainly been based around his songs (three to two against G. T. Moore’s offerings), he had only five writing credits on this lengthy, twenty-one-track follow up. Was he being sidelined?

The songs just weren’t there, he explains, shaking his head.

In fact, the sensitivity of Apps’s songwriting is all but smothered on Heron’s second album. Twice as Nice opens with Moore’s goofy “Madman,” and you can debate whether Heron was looking, here, to either confuse or alarm, but from the get-go it sounds like a completely different band: fully electrified, like a looser version of Pye label-mates the Kinks. The frenetic jam session that ensues is followed by what would be the album’s sole single, Apps’s “Take Me Back Home”: “Take me back home to the air that’s warm / And the silent soaking rain.”

He might as well have been singing to that field in Appleford. His songs now appear as little gems buried under unfocused arrangements, subsumed in middle-of-the-road settings. At least Moore’s salvaging of yet another obscure Dylan song this time reveals Heron to be capable heirs to the sort of folk-rock reinventions Fairport had accomplished when digging into Dylan’s back catalog. Apps even manages to come out swinging and out-Band the Band at one point, on the straightforward roots rock of “Getting ’Em Down”—and he does so in under two minutes, as if the track was merely being thrown off as a joke, an ironic zinger to signal just how far Heron had wandered from its soft-footed debut.

Heron’s weaknesses had come to the fore by this point, and it was only a short time before these hairline cracks indeed became too numerous for the band to carry on. The fundamental problem may well have been G. T. Moore. Moore, a gifted songwriter and guitarist in his own right, never actually considered himself a full-fledged member of Heron. The band, for Moore, was a sideline, a foothold into the industry. Added to which, his behavior could be as erratic as his musical direction; one story has him showing up for a gig without his guitar and stating his desire to take up the pennywhistle instead. After parting company with Heron after touring Twice as Nice, he was next found fronting his own reggae collective.10

Dropped by Dawn, Heron lingered on in various loose formations: backing the Iranian chanteuse Shusha on two of her mid-’70s releases, also privately recording an album in 1976. Apps meanwhile found himself involved in a new Pete Eden venture, starring as Rory the Lion on a Banana Splits–style children’s TV show called Animal Kwackers.

I wonder aloud if Apps regrets any of his post-Heron career and he shakes his head, fingering another smoke. It is then I notice he’s wearing a homemade thimble. He later tells me it’s there to hide an old wound. Back in the ’80s when he had a stint as a landlord of a village pub, a door in his establishment had very nearly ended his guitar playing.

There’s also the story about John Peel, in which Peel phones up Apps shortly after Heron’s demise and offers him a solo deal on Dandelion Records, only to phone back again, two weeks later, to say that the boutique record label has gone bust. Does Apps not regret that missed opportunity? Again, the answer is no. It was out of my control, he tells me, his hand riffling through his sparse patches of gray hair.

I explain it’s a preoccupation of mine, listening to the Heron albums and imagining what might have been. Say, if Apps had gotten that record contract with Peel, what it would have sounded like… What might have happened if, following Moore’s departure, the band had emigrated to Laurel Canyon, recording albums out on David Crosby’s patio.… What if they’d been signed by Joe Boyd to his Witchseason label.… Or what might have happened if the band had simply released “Yellow Roses” as the first single? Might it have turned up in a Volkswagen commercial a quarter of a century later, à la Drake’s “Pink Moon,” thereby giving its music the attention it deserved?

Apps just smiles, his rustic scrabble of teeth flashing for a moment before he shyly hides them away again. He smiles as if to show how thankful he is to be where he is now. As if to say, upon reflection, that had things been any different, he might not have ended up here, where he is today, having survived his many misadventures and what he calls his “dark days,” also having befriended George Harrison, still recording, still performing occasionally with the remainder of Heron. It’s a smile as pensive as any autumnal-folk masterpiece. Still saying nothing, he begins pawing at the collar of the spaniel whose head now rests at his knee. Then he offers me another tea, and as he does so, reaching for the now-empty cups, a robin lands gracefully at the edge of the picnic table.

The bird lingers. It makes me think of all those other birds heard singing in the background of Heron’s albums. I also think of that young, somehow lost-looking musician in his red jumper again. Then I remember all the lonely, lovely ballads of Roy Apps.

Look who’s come to visit, he whispers.

I’m unsure if he is speaking to me or to the robin, but it’s the same voice, I realize, the exact same bittersweet sigh heard at the opening of “Yellow Roses” all those years ago.

Yellow roses may be all he can bring you

But no night bird can sing the songs he’ll sing you

So when he wants you, you just have to stay

You just have to hold him, it’s the only way