I. THE TRAM TON PASS

On October 29, 2013, Scottish botanist James “Jamie” Taggart flew from London to Hanoi via China. He was embarking on his third plant-hunting expedition overseas, and his first solo trip. Originally, the plan was to reunite with Quang Son, a guide he had befriended on a trip to northern Vietnam in 2011. But Son was out of town on a trek when Jamie emailed him shortly before his trip. Jamie was undeterred. He had long anticipated a return to Vietnam. He decided to go it alone, and the decision only made him more excited. For about a month before he embarked, Jamie called his friend and fellow plant hunter Ian Sinclair almost every night to bounce ideas off him about where the good hunting would be.

Jamie planned to concentrate on the upper slopes of the Hoang Lien mountains, whose lower slopes he’d explored in 2011. On his first night in Vietnam, Jamie stayed in a bed-and-breakfast in Hanoi. He texted his father to say he had arrived safely, but had not slept well, and that he would proceed to Sa Pa, the town that would be the base for the expedition, in the morning. “Three days should do the high ground,” he said.

The next day, Jamie took the over-night train to Lao Cai, a city of about one hundred thousand people just across the Red River from China. The trains are well appointed, but the combination of a bumpy ride and a dawn arrival make a full night’s sleep impossible. It’s one of those journeys where you get to know the whole carriage through involuntary eavesdropping. Outside, banana plants proliferate like giant dandelions, and tropical moisture makes for a near-perpetual mist.

But on October 31 there was little mist. It was a clear day and the sun was whole and bold as a yolk. Jamie had decided to stay in one of the quieter guesthouses in central Sa Pa, the Ngoc Anh. It was located on a back street overlooking the church, not far from the sunken courtyard where locals sat on the steps and played kick-around soccer. Jamie was given a room on the third floor and he dropped off most of his stuff there, leaving a bag that contained most of his clothes, his passport, and several of his note-books. He took his camera and phone with him. He had forgotten to bring a phone charger but he had a spare battery and he told his father, when he texted from Hanoi, that he’d managed to recharge his phone during the stop-over in China. It’s unclear how long that charge lasted.

At about 9:30 a.m., a little more than an hour after he arrived on the night train, Jamie was picked up by a motorcycle taxi driver, a short, safely, but had not slept well, and that he would proceed to Sa Pa, the town that would be the base for the expedition, in the morning. “Three days should do the high ground,” he said.

The next day, Jamie took the over-night train to Lao Cai, a city of about one hundred thousand people just across the Red River from China. The trains are well appointed, but the combination of a bumpy ride and a dawn arrival make a full night’s sleep impossible. It’s one of those journeys where you get to know the whole carriage through involuntary eavesdropping. Outside, banana plants proliferate like giant dandelions, and tropical moisture makes for a near-perpetual mist.

But on October 31 there was little mist. It was a clear day and the sun was whole and bold as a yolk. Jamie had decided to stay in one of the quieter guesthouses in central Sa Pa, the Ngoc Anh. It was located on a back street overlooking the church, not far from the sunken courtyard where locals sat on the steps and played kick-around soccer. Jamie was given a room on the third floor and he dropped off most of his stuff there, leaving a bag that contained most of his clothes, his passport, and several of his note-books. He took his camera and phone with him. He had forgotten to bring a phone charger but he had a spare battery and he told his father, when he texted from Hanoi, that he’d managed to recharge his phone during the stop-over in China. It’s unclear how long that charge lasted.

At about 9:30 a.m., a little more than an hour after he arrived on the night train, Jamie was picked up by a motorcycle taxi driver, a short, sturdy, animated man named Huyen Tran Ngoc, who would take him to the gates of the Hoang Lien National Park, at the foot of the highest mountain in Vietnam, Fan Si Pan. Jamie was in high spirits as he climbed onto the bike. On his back he carried a small bag containing his camera, his note-books, and a map. From the round-about outside the church, Ngoc took the road along the river and turned north onto Highway 4D.

The drive to the park is a favorite of motorcyclists from all over the world. Just before Sa Pa, terraced rice fields appear, carved into the mountainside like the tiers of a penny fountain. As the road coils upward, cliffs rise to the right, and the foothills disperse to the left. All around, thick vegetation gives the surface of the mountains the spongiform appearance of broccoli.

Jamie arrived at the entrance to Hoang Lien around 10 a.m. Ngoc was surprised when Jamie waved off his efforts to schedule a pickup time, as day trippers typically do. Clearly, Jamie was not entirely sure what time his work on the mountain would be done. He entered Ngoc’s number on his phone and paid him one hundred thousand dong, or about five dollars, for the ride.

Sau sells tea from a stall opposite the park gates, where exposure to the elements has toughened her skin but not her features. She saw Jamie squatting on his haunches near the arched entry-way. She and her colleagues, whose stalls are waterproofed with blue tarpaulin and shaded by old rugs, beckoned to him, trying to sell him some of the green tea that is a cornerstone of the daily routine in this part of Vietnam.

Jamie declined the offers. After a short rest, he rose to his feet and walked in the direction of the Tram Ton Pass, a popular scenic lookout. As he rounded the bend, Sau watched him go, unaware that she would be the last person to see him alive.

A year later, when I started investigating Jamie Taggart’s disappearance, almost nobody believed that he could have attempted the high ground that day. Jamie was fresh off the night train and, with a whole month for his field-work, he had no reason to push him-self. Plus, he was getting a late start. In late October, the sun sets just after 5 p.m. in this part of Vietnam, and it becomes dim around 4. He knew first-hand how treacherous the slopes of the Hoang Lien mountains are, knew how slick rocks could be concealed by bam-boo and briars, how gentle slopes could end abruptly in jagged cliffs.

The high ground of Hoang Lien National Park is an easy place for a person to come to harm.

In 2001, a British student, Amy Ransom, was on the Fan Si Pan trail with guides when she fell into a ravine and died. In 2016, twenty-two-year-old British student Aiden Webb, an experienced mountain climber nicknamed “Hercules,” wandered off a trail and suffered a fatal fall. Jamie likely suffered a similar fate.

For months he was missing. Jamie’s family and their community raised funds to commision search parties, but nothing was discovered. Then, on December 15, 2015, a local farmer discovered Jamie’s remains at the bottom of a waterfall, on the outskirts of Hoang Lien, about a four-hour hike from the spot where Sau last saw him.

He had apparently fallen while scaling the waterfall.

Despite the tragedy, Jamie’s father, Jim Taggart, seemed to find some solace in the fact that Jamie had died in Hoang Lien.

“He was where he wanted to be,” he said, when I called him around the time that Jamie’s body was discovered.

Many of the people I spoke to—private investigators, Vietnamese officials, expats, friends, botanists—found it more difficult to understand Jamie’s thinking than his father had. Most of them responded with dismay: what had possessed him? Why would anyone put their life in such danger for the sake of a plant or two?

II. ROOTS OF A PLANT MAN

During autumn, the mountains between Loch Lomond and Jamie’s hometown of Cove in western Scotland are ginger with bracken. These are the mountains where Jamie fell in love with hiking. Cove is a tiny hamlet near the village of Kilcreggan, on one of the peninsulas that proliferate along the west coast of Scotland like the sprigs of a thistle plant. It is home to the Linn Botanic Gardens, a small but reputable plant collection that Jamie’s father founded, and where Jamie worked most of his adult life.

One afternoon in late September 2016, I walked past the wooden kiosk at the entrance to the gardens, where Jamie had handled admissions before his disappearance. Just past the kiosk, I found Jamie’s father, Jim. Standing near a ladder, he held garden shears and long-handled clippers with which he’d been pruning the rhododendrons, magnolias, and other mountain plants that surrounded us. The elder Taggart has something of the druid about him, his white beard as fecund as the gar-dens themselves, his voice soft and musing. He greeted me warmly and introduced the plants in a wry manner—“good for making placards,” he said of the bamboo—and reminded me that he still protests the nuclear submarines that use the nearby fjord.

Jim Taggart holds a PhD in botany and lectured on the subject at Trinity College, Dublin, before he met Jamie’s mother, Jill Mary, in Oxford. Jamie was born on January 19, 1972, the couple’s third child in as many years. Shortly before Jamie’s birth, Jim had purchased Linn Villa, a three-acre estate established by the actor Hugh Grant’s ancestors in 1860. As soon as he moved in, Jim revived the villa’s Edwardian gardens with what he described as a “fairly catholic” collection of plants and trees from China, Peru, and elsewhere. Today, it is a struggle to keep the garden in check. Jim showed me some of the ferns that Jamie had brought back from a previous trip to Vietnam. He was tending these plants like a flickering fire.

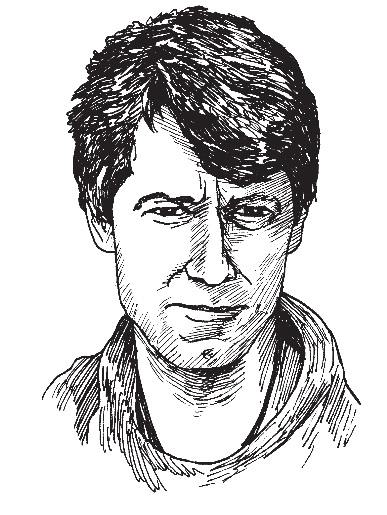

Jamie helped to raise this plant kingdom, and it helped to raise him. In the villa, a beautiful ivy-bound house, his father has hung a blown-up photo-graph of Jamie at the potting bench as a boy. “That about sums him up,” he said. Jamie’s brother, Peter, added that “by the age of five [he was] well versed in botanical Latin.” In the only video footage I have seen of Jamie, he is showing guests around the Linn. His athletic build reflects his hobby of long-distance running and his side job as a volunteer fireman. At one point, he slaps the trunk of a tree in the affectionate, intimate manner of a mahout greeting a favorite elephant. His accent is curious: a placeless mellifluence occasionally giving way to more distinctive Scottish notes. His dark hair is fading to a wolfish gray. His full, confident voice may be for the benefit of the camera; in private, friends and family say, Jamie was always soft-spoken, more of a listener than a talker.

Jill Mary left her husband in 1978, and then a torturous divorce ensued that left scars on everyone involved. Jamie lived with his mother and his sister, Janet, in the north of England for several years while Peter remained with their father. Jamie, already collecting plants of his own, pined for the Linn. He moved back at the age of twelve and—apart from sitting for his botany degree at university in Glasgow and his plant-collecting missions overseas—it remained his home base.

To shield the property from the costly divorce, Jim Taggart planned to transfer the Linn to his two sons, but Peter and Jamie had a falling out. Peter moved to England and lost contact with Jamie, who managed the gardens with his father, eventually moving into a cottage on the property. In their book about the Linn, Another Green World: Encounters with a Scottish Arcadia, Philip Hoare and Alison Turnbull aptly describe this residence as a “small, utilitarian cottage, a kind of glorified gardener’s shed.” Jamie was diagnosed with dyslexia; he struggled at school and left early, taking an unconventional route through college. He went to work at the Benmore Botanic Garden, a nearby affiliate of the Royal Botanic Garden Edinburgh, one of the oldest cultivated gardens in the world, and took college courses while he worked; he later studied full-time at the University of Edinburgh and graduated with a degree from its revered botany department.

In addition to his love for botany, Jamie was heir to wanderlust. His father had hiked in Arctic Greenland and his mother was a “Sandalista,” picking coffee in Nicaragua around the time of the Nicaraguan Revolution. Jamie showed an early appetite for adventure, too. While living with his mother, he scaled a Derbyshire crag known as the Black Rocks without the aid of ropes. Jill recalls when she and Jamie took a rowboat out on the lake, during a trip to Lancashire’s Lake District. The weather suddenly changed, Jill remembers, and Jamie began to row for the shore at a frantic speed. It was a frightening moment, the kind of moment I’ve experienced myself, when a slight shift in conditions turns a jaunt in the great outdoors into a traumatic event. But, in the days after, Jamie seemed unfazed by the experience. To a romantic, I suppose, it hardly matters whether adventure or misadventure generates feelings, as long as the feelings are powerful.

III. FIRST EXPEDITIONS

Sa Pa united Jamie’s tastes for botany and adventure. The town was built up by the French in the nineteenth century as a hill station for imperial officers seeking to escape the summer cauldron of Hanoi, and was also a refuge for ethnic groups such as the Hmong, Dao, and Tai, who preserved their tribal way of life in the borderlands after being driven out of China and other parts of Vietnam. Today, attractions like hiking (at 3,143 meters, nearby Fan Si Pan is one of the highest mountains in Southeast Asia), wild cannabis plants, and Hmong crafts and culture have established Sa Pa as a backpacker colony.

Hoang Lien National Park, which includes Fan Si Pan and surrounding peaks, is only about twice the size of Manhattan, but it’s home to more than two thousand species of plants. The park was off-limits to scientists as recently as the 1980s, when Vietnam-ese and Chinese troops still clashed regularly in a dispute over the nearby border. The first extensive exploration since those conducted by French colonial-era botanists began in the 1990s, when political reforms allowed local scientists to draw on the resources of major botanical institutions such as Britain’s Kew Gardens and the Missouri Botanical Garden.

Because of the confluence of habitat extremes—considerable altitude, persistent mists, tropical warmth—many plant species in the Hoang Lien mountain range, a southeastern spur of the Himalayan system, differ in size and shape from their relatives, even in adjoining provinces. Aboriginal strains of the magnolia family, close in appearance to the famous Southern belle, grow in the park, as well as rare varieties of temperate-zone trees like maples and horse chestnuts, and tropical flowers such as camelia (the tea plant) and orchids.

Orchids, the Westminster show dogs of the botanical world, were Jamie’s first love. As a boy he hunted for them. Following a cactus phase in his teens, Jamie grew interested in another family of plants that proliferate around Sa Pa: rhododendrons. This diverse family of flowering trees also has a passionate following, and Jamie served as an officer of one of the many UK rhododendron societies. One rhododendron hunter, Charles Darwin’s friend Sir Joseph Dalton Hooker, famously crossed the Himalayas in winter to document a rare species. Another collector, scion Lionel Nathan de Rothschild, loved rhododendrons so much that he often described himself as a “banker by hobby—a gardener by profession.”

There are enough hues of rhododendron blossoms in Hoang Lien to fill a housepainter’s sample book. As an adult, Jamie acquired a taste for less-showy flowers and for non-flowering plants (known as gymnosperms). These are the jazz records of the flower world; the senses must be trained to appreciate their beauty. Among his favorites were hardy lilies, rock-dwelling flowers like primula (a relative of the primrose), and gymnosperms like schefflera (shrubs with shiny, seven-fingered leaves that are popular in hotel lobbies around the world). The mountains of Vietnam are rich in all these families.

“That area of Vietnam has a collision of several different floras—you get the Himalay coming from the west, then the Japanese-Korean flora coming in from the east, and Australian flora coming up from the south—they all sort of hit right in that area,” says American botanist Daniel Hinkley, who has made several studies of the plant life in the region. “It wasn’t glaciated during the last glacial epic; it didn’t get wiped clean like a lot of the mountains did farther north.”

As recently as 2002, an American botanist named Daniel Harder discovered a new conifer tree in north-ern Vietnam known colloquially as the Vietnamese golden cypress. It was a moment comparable to the first con-firmed sighting of a narwhal: only a handful of new conifers had been identified since 1948. Convinced that some species in the area remain undocumented, Russian botanist Leonid Averyanov has called for “urgent botanical exploration” of the park, noting the “meager” literature on the area and the “deforestation, degradation and destruction” of the habitat. In recent years, development has accelerated. During his first visit to the area, British botanist Alan Clark saw a rare—and possibly unique—rhododendron species growing in a clump on a roadside near the park. In 2011, he took Jamie and Hannah Wilson, another British botanist, to the site to see the copse for themselves. But the road had widened and the rhododendrons were gone.

Jamie first came to northern Vietnam in 2011 with Clark and Wilson. Jamie’s primary goal on this trip was that of every taxonomic botanist: to discover and document plants unknown to science. A veteran plant hunter and an authority on rhododendrons, Clark had first visited Sa Pa and Fan Si Pan in 1991. He had met Jamie while the younger man was working at the Ben-more Botanic Garden, and they stayed in touch. In 1995, Jamie, recently graduated from university, accompanied Clark and a group of botanists to Yunnan Province, in southwestern China, which is part of the same “floristic system” as northern Vietnam. Guides took them to mountains where the plants had never been cataloged, Clark said, and the party identified several new rhododendron species.

The three botanists traveled with Quang Son, a guide who now lives in Sa Pa. After some time at lower altitudes in the northeast, Son took the party back to the Sa Pa area to spend a couple of weeks in and around the national park. Jamie packed in as much botanizing as he could. He sometimes rose early and tramped through the forest alone in search of rare schefflera and ferns that were of particular interest to him.

While they were traveling together over the years, Clark was struck by Jamie’s daring. He remembered one incident, in particular, when they were touring a lakeshore in Yunnan. Clark saw something of interest on a nearby mountainside. “I thought I’d spotted a new variety of rhododendron,” says Clark. “I said: ‘What do you reckon, Jamie?’ These mountains were like pyramids. He just backs up across this flat bit of area, takes his boots off, takes his socks off, and sprints and literally goes straight up this mountain.”

During their group hikes, Jamie sometimes scrambled up trees when he saw orchids or epiphytic rhododendrons—or just for the hell of it. Clark remembers pointing out a mistletoe with pink berries high up in a magnolia tree. Jamie said he’d never heard of that species and then, a few minutes later, Clark realized he’d lost sight of Jamie. He called out for him. “I’m up here,” Jamie said. He was seventy feet up a tree, and the tree was swaying eight feet in either direction.

IV. CAN A HUNTER BE A CONSERVATIONIST?

In Pitlochry, Scotland, a couple of hours northeast of Cove, there is a botanical garden called the Explorers Garden. It is dedicated to some of the greatest botanists of the British imperial age (many of whom were Scots). They include nineteenth century naturalist William Menzies, who hunted for plants on Hawaiian volcanoes and reportedly introduced the mon-key-puzzle tree to Britain after spotting an unusual nut in his dessert during a dinner in Chile.

From the very start, the romance of the plant hunters had a darker side of power politics and colonialism. Menzies and his cohorts made major contributions to the scientific annals, but some allege they also contributed to the rapine of the colonial world. There’s even a school of thought, expressed by Brian Friel in his masterful play Translations, that the very act of naming places and things in the colony was an act of subjugation.

In Toby Musgrave’s The Plant Hunters: Two Hundred Years of Adventure and Discovery around the World, a 1998 illustrated work, Sir Joseph Banks appears as the archetype of the natural scientist as imperial officer. Banks, a skillful sketch artist, sailed around the world with Captain Cook in 1769, just as the Latin classification system developed by Carolus Linnaeus was catching on. Banks brought back the first impressions of many Southern Hemi-sphere plants, including the eucalyptus, and upon his return “persuaded [King George III] that he should have the world’s most diverse collection of plants and that the logical location of this collection was the Royal Gardens at Kew.”

Kew and the on-site herbarium (as archives of pressed flowers and plants are known) became important centers of plant science. Like the Lon-don Zoo later became, Kew was also a symbol of colonialism, the modern imperialists’ version of the Roman triumph, where the public came to gaze at prizes brought home by their conquering empire. The world’s largest flower, the Rafflesia arnoldii of the Indonesian jungle, was described by botanist Joseph Arnold and named for his sponsor, Sir Stamford Raffles, the bloody conqueror of Java and the founder of Singapore.

Britain’s chief colonialist rival, France, also converted the Jardin du Roi in Paris into a public facility for naturalism. The French complex included the Museum National d’Histoire Naturelle and the world’s largest herbarium, including tens of thou-sands of Vietnamese species. Kew and its Parisian rival would also become models for countless botanical gardens that are still visited by hundreds of mil-lions of people worldwide, including the Linn. And Jamie was instrumental in the Linn gaining recognition, painstakingly compiling the requisite plant catalog. In 2013, shortly before he left for his second trip to Vietnam, Jamie updated the catalog—now more than 2,500 species strong—for the appendix to Another Green World.

In the postcolonial world, the argument still rages about whether the scientific benefits of plant collection justify the removal of natural riches from countries like Vietnam. The changes in international law mean that small botanical gardens like the Linn must document their acquisitions in a way that Kew and the great imperial gardens never had to worry about when building their collections.

The 2010 Nagoya Protocol was an effort to strike a balance between patrimony and science. The international agreement sought to protect biodiverse nations like Vietnam from exploitation while giving international scientists access to plant materials under certain terms.

“[There were] many cases where the pharma industry went to Brazil or Indonesia, took plants in the forest, brought back molecules from the plants, and made millions,” said Sophie Leguil, a UK-based plant conservationist who blogs about plant issues as Naturanaute. “The Nagoya Proto-col was supposed to ensure this would not happen again,” she says.

Scientists and botanical gardens in the West complain that the Protocol and other laws governing the exchange of plant material are too onerous. All agree that unscrupulous collectors who pluck rare orchids or plough up rhododendron bushes should be dealt with as harshly as ivory collectors (Hinkley has reported seeing evidence of this around Sa Pa as recently as March, 2016). Collectors trade some flowers, including rare orchids, for sums that can go into the thousands of dollars. This is one of the prime causes of extinction in the wild: over-collection.

In northern Vietnam, collectors have a rapacious history. The Russian botanist Leonid Averyanov identified a new species of orchid in the mountains near Sa Pa, in 2009. Once pictures of the flower appeared on the inter-net, collectors descended on the region. According to Averyanov, 99.5 percent of the flowers in the wild disappeared within six months of his discovery.

But should botanists who collect seeds be lumped into the same cate-gory as these trophy collectors? That’s how the letter of the law would have it. The permitting process for any kind of collection in Vietnam can be excruciating. It may take up to six months just to get an email back from the relevant authorities, and it can take as much as two years to process a permit to collect seeds. As a result, Jamie opted not to file for a permit to collect plant material. And the decision hurt him—but for reasons he could not have predicted. After he disappeared, Jamie was hard to trace partly because he never once logged into a national park visitors’ book.

Some ecologists say the animal kingdom may be on the cusp of a “sixth wave” of mass extinctions. In the plant kingdom, mass extinction is already happening. “The background rate [is] one to five species a year go extinct,” said Thomas Philbrick, a Western Connecticut State University botanist who studies plants that grow near South American waterfalls. By some definitions, “the rate of extinction now is increased by one thousand to ten thousand times,” Philbrick said. “Now we’re talking about ten to fifteen species going extinct per day. During the course of this telephone conversation,” he told me, “it’s predicted that a species will have gone extinct.”

The main reason for the acceleration in extinction is likely climate change. A 2015 study in Science found that one in six species will be threatened if climate change proceeds as expected. Species native to transition zones like Hoang Lien are more vulnerable, and will likely be the first affected. A one-degree temperature shift doesn’t seem like a lot, but for an orchid on the slopes of Fan Si Pan, it can be the difference between toughing out the winter and freezing to death.

The New York Times recently reported that Hmong families farming the historic rice terraces just outside Sa Pa were blaming failed harvests on harsher summer and winter weather. The 2014 blizzards and forest fires on Fan Si Pan not only thwarted the search for Jamie; they destroyed wide stretches of forest. These kinds of events are harbingers of what changing temperature and weather patterns will do—and are doing—to plants and animals.

Climate change and over-collection are not the only threats facing Hoang Lien. When I took the main Fan Si Pan trail in March 2015, it was as heavily littered as a 1980s fairground. Cigarette butts, plastic water bottles, candy wrappers, tissues—the specimens of trash were almost as diverse as those of the plant life. Unlike great Amazonian preserves such as Peru’s Manú, Hoang Lien is easily accessible from a major city: Hanoi, one of the fastest growing metropolises in the world, is now only four hours away by bus. In February 2016, a roughly $130 million cable car opened to the world, capable of ferrying two thousand backpackers to the summit in an hour. Since then, it’s garnered 276 TripAdvisor reviews.

In addition to tourism, there is the issue of monoculture. Traditionally, the Hmong people cultivated opium in the mountains around Sa Pa. These operations were small and relatively low-im-pact, because of the taboo associated with the drug and the threat of a crack-down. A decade ago, that crackdown came, and most Hmong switched over to growing cardamom, which is almost as lucrative as opium, selling for as much as four dollars an ounce. This industry has helped the Hmong but harmed the environment. Now working with a legal crop, farmers have increased the size of their operations, clearing swaths of forest for the broad-leafed spice. On some slopes in Hoang Lien, so many patches of forest were cleared, it looked as if the mountains were tearing their hair out.

In every landscape, there is tension between usage and conservation. Under which category did Jamie’s work fall? Reputable botanists object to the label of “plant hunter” because they see their work as closer to that of zoologists who tag rare animals in the wild than to the sport of big-game hunters. By collecting seeds, they are affecting the plant as a tranquilizer affects an elephant, but they are not doing it any permanent harm. And, they insist, their work does help serve the cause of conservation in a crucial way. As Jamie’s friend Hannah Wilson says, “You can’t save something that doesn’t have a name.”

V. ON THE MOUNTAIN

Jamie’s hike would have taken him on a rapid ascent as he crossed the first line of ridges. Higher up, many of the plants and trees would have been at once familiar and alien. At some stage, Jamie left the trail altogether. “He would have found a path to get off the road, then seen if he found a promising stream,” Wilson said. “He’d follow that and just climb as high as he could—and he was a very good climber.”

I tried to follow a similar route on the Hoang Lien mountains for a very short time in March 2015. Jamie was still missing at the time. I was accompanied by my brother Rich, our guide (the self-taught botanist Uoc Le Huu), and Hmong porter Giang A. Tung. Our group started out around seven in the morning, from the hut where hikers stop to break up the ascent of Fan Si Pan. Rather than turning left to attempt the summit, we turned right, and started up what looked like a wide, rocky streambed. The land around the rocks had been cleared by a landslide.

At one stage, our group stopped for a break, eating cubes of a kind of shortbread supposedly popular with the soldiers of the Vietcong. The guide Uoc tapped me urgently on the shoulder, much as an animal tracker might alert a safari group to the presence of a furtive leopard. I inhaled and smelled the sort of simultaneously fresh and sweet odor that soap manufacturers dream of. It was, Uoc said, the scent of a daphne flower. I looked around but could not find the source. I have often smelled things I cannot see, of course, but I have never encountered a flower’s scent that’s so strong it permeates the atmosphere as aggressively as steaming manure or burning oil.

We zigzagged up the slippery rock, sometimes in a standing position, sometimes hunched to grab at fingerholds. I slipped several times, arresting my slide only by grabbing tufts of grass. This was in the relatively dry month of March; in October, when Jamie was here, the stones would have been far more treacherous. When I reached the top of the clearing, my brother stood, shaking his head at the bamboo in front of him. Bamboo poles living and dead were stacked so thickly that I could not see whether the ground below was slippery stone or sticky mud. My brother and I tried to follow the trail cut by Giang’s machete, but it was not always possible to detect. I grabbed at the bamboo for balance but they came loose in my hand, the shallow roots giving way under pressure. At one point, I had to clamber up a smooth rock that was about shoulder height. The bamboo had worn me out. My brother reached down and tried to pull me up. The top of the rock he balanced on was narrower than his foot.

VI. THE SEARCH FOR JAMIE TAGGART

The owners of the guesthouse, who did not wish to be named, were expecting Jamie to keep his one-night reservation, to return with Ngoc on the motorbike. He had gone to the mountains and had not returned before nightfall. The owners said they contacted the police at around eight thirty that night.

A local police investigation began shortly thereafter, according to someone familiar with the thinking of the Vietnam-ese police, who also did not wish to be named. Neither British nor Vietnamese authorities in Hanoi were alerted initially, because other westerners had also occasionally gone off the grid, typically extending stays with local Hmong families, according to this person.

By all accounts, the investigation into Jamie’s disappearance moved slowly. The British embassy was not informed until November 30. Efforts by Police Scotland to trace Jamie via cell-phone signals yielded nothing. The slopes of Fan Si Pan and surrounding mountains have surprisingly good cell-phone coverage, but there are dead zones, and Jamie’s phone may have been out of power.

Some of the most intensive mountain searches were conducted by Jamie’s old friend and guide Son, who returned to Sa Pa in early November and went into the mountains around November 14. Upon his return, Son found an email message from Jamie, asking if he would accompany him to the mountains again. Then he heard a rumor from a police contact that a westerner was missing on the mountain. In a moment of agony, Son under-stood. When I met him at his house in central Sa Pa more than a year after Jamie’s disappearance, the pain was still evident on his face and in his voice. In 2011, the two had camped together, and Jamie had visited Son at his home. Wilson remembers Jamie and Son confiding in one another even after the trip. Jamie was “like a brother,” Son told me.

November 29, the day before the Vietnamese authorities notified the British embassy in Hanoi that Jamie was missing, was the day Jim Taggart had expected Jamie back in Scotland. On December 1, the UK consular office contacted Jim Taggart and told him what little they knew about his son’s case. The community in Cove and Kilcreggan rallied around the Taggarts.

Luong Van Hao, the director of conservation at Hoang Lien National Park, oversaw the private searches and those involving his own park war-dens. Using funds raised by Jamie’s family to pay porters, Son led several searches in the park, beginning around December 20. Photographs show the Hmong porters filing through a wooded area, plastic ponchos streaked with rain. This rain was followed in short order by blizzards, which became so heavy that the search had to be abandoned. That December, the snow came all the way down to Sa Pa for the first time in living memory. In early 2014, the searches were again interrupted by extensive forest fires. One of Son’s porters suffered a bro-ken leg. Exhausted and running out of money, he had to give up.

The British urged the Vietnamese to keep the investigation open. On July 10, 2014, the UK minister of state for the Foreign and Commonwealth Office, Hugo Swire, raised Jamie’s dis-appearance with his Vietnamese counterpart, Vice Minister Bui Thanh Son.

Vietnamese officials had concluded that Jamie could not have been in the park; they developed a theory that he’d slipped over the border to China, even though there’s no evidence he had any intention of going there.

Jill Mary was the first member of Jamie’s family to come to Vietnam. I met her in Sa Pa on March 18, 2015, in her hotel, a few blocks from the guesthouse where Jamie had stayed. Jamie’s body still had not been found. As we talked, she intermittently cried, overwhelmed by anguish. On the bus ride through the lush mountainsides around Sa Pa, she said she had had an epiphany. She was now convinced that Jamie’s fate was tied to this wilderness rather than to any foul play. Here, she said, she felt close to her missing son.

The next day, representatives from the British embassy took us to the spot where Jamie was last seen, where we met Sau, the tea seller. Jill Mary said she was nervous, and there was a restlessness, a resistance to stillness in her demeanor. When we met with Vietnamese and British officials, however, her demeanor changed. She fixed her eyes, so bright they sometimes seemed backlit, on the park executive. She talked quietly and demanded answers. She refused to be fobbed off, continually pressing the Vietnamese authorities (who did not want their names used in this account) to reopen their search. With the park executive’s help, she deter-mined which botanically rich areas had already been searched and which had been missed. As she looked out over the steep valley known as Heaven’s Gate—one of the areas that had been overlooked—Jill Mary told me how excited her son would have been by the exposed stone, which some of his favorite plants would have hugged. She did not know that she was, by my reckoning, only a mile from the waterfall where Jamie’s body would be found a few months later.

VII. WHAT WAS HE THINKING?

As we waded uphill through the sea of bamboo, my brother and I were out of our depth. When the bam-boo cleared and we reached a ridge, I felt the relief of a swimmer reaching the shore. The view opened up on all sides. To our left was the peak of Fan Si Pan; behind us, across the valley, was the handful of peaks known as the Five Fingers. Three or four miles to our right was the waterfall where Jamie stopped on October 31, 2013. Short red rhododendron bushes formed a chain down the western side like pockets of forest fire. Uoc pointed out places where sheer rock face peeked between the bushes. My brother and I, novice hikers, saw only the danger in those slippery rocks, but seeing the mountainside through Jamie’s eyes, Uoc thought of the lilies and primroses that might grow beside them, particularly if there was water nearby.

When I told people whom I was writing about, many seemed puzzled.

Their response was echoed by that of the exasperated Vietnamese authorities: “What was he thinking?” Why would Jamie scale the bank of that waterfall, which had a reported eighty- degree gradient?

Sitting there, elated to have emerged from the bamboo and to see the valleys open up, I could imagine what he was thinking. On an assignment like this, heart beating quickly at the thought of a find, there’s always the urge to push higher.

Jamie had probably caught a glimpse of a fern or even a primrose, a flower that can bloom in the winter, and climbed up for a better look.

As I imagine it, he stops on a precipice where the plant grows. I see him inching across the rock, just wide enough to bear one foot at a time. Even from five feet away, he recognizes the flower as a new, or extremely rare, species; he must get closer to collect its seeds. The rock is slick with the water-fall’s mist. Carefully, Jamie adjusts his footing, jamming a boot into a crevice or onto a root and leaning out to the very edge of this precipice. He is holding the waterfall’s rock wall for support. I see him reaching out across the gap between the rocks for the flower. Like Daphne evading the outstretched arms of Apollo at the riverside, the flower shimmies in the wind, forcing him to inch closer. It’s a step too far. His foot slips. For an instant, his heart is seized by that same grasp he felt out on the lake as a boy—nature’s trap snapping shut. He scrambles, but he knows it’s too late. His arm is still extended, reaching for a flower that will forever elude his reach.

What was he thinking? He was thinking of Menzies and the great Scots explorers. He was thinking of Mother Nature on the run from climate change and high-capacity cable cars. He was thinking of the beauty of the flower he had just discovered, and whether anyone else would ever see it. For what is the act of discovery if not leaving the safe foothold of the known to reach into the abyss?