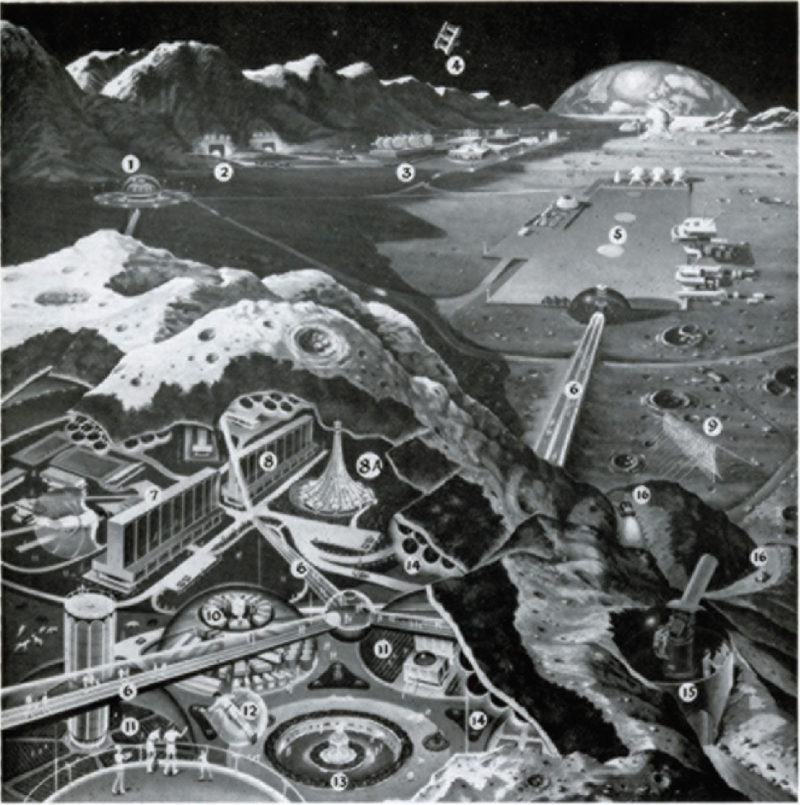

On May 28, 1967, Maurice Lavanoux read an article in the New York Times Magazine with the headline after apollo, a colony on the moon. The author—Isaac Asimov—explained how such a thing could happen: by constructing residential caverns beneath the moon’s surface, settlers could create a livable climate powered by solar energy. “Merely reaching the moon is no end in itself,” Asimov wrote. “Having reached it, cannot we and the Soviets and any other nation that cares to join the venture combine to explore it, develop it and make it a home for man?” Lavanoux was titillated; this confirmed what he had learned a few years earlier, while judging an oral presentation by a Princeton architectural student: that lunar colonization was not only possible but imminent. (The student, William R. Sims, went on to design parts of Epcot Center.) Lavanoux was the secretary of the Liturgical Arts Society and the editor of Liturgical Arts, a quarterly journal dealing with the arts of the Catholic Church. Emboldened by his findings, he decided that if there was to be a colony on the moon, there should certainly be a chapel, and if there was to be a chapel, he would be the one to build it.

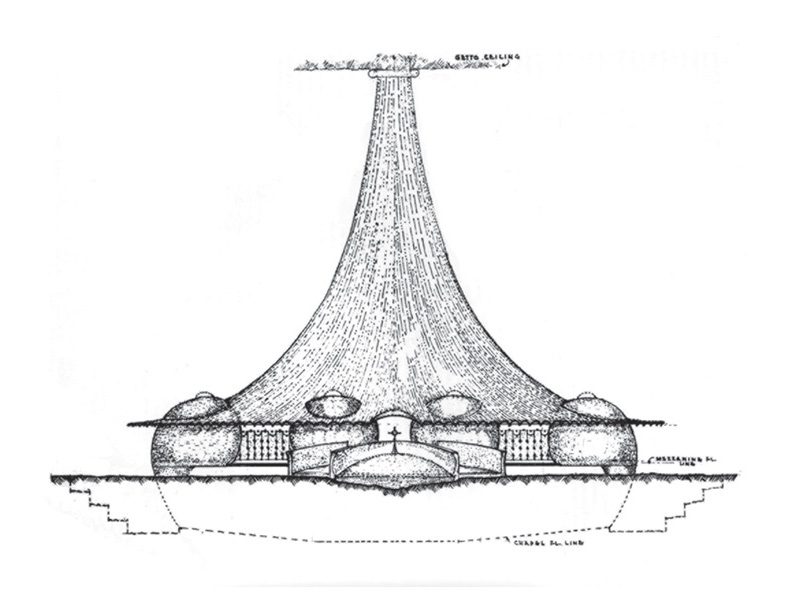

Lavanoux already had an architect in mind—a man named Mark Mills, who had spoken to him of a “dream church” he hoped to build someday. Based on his interest in the Princeton thesis, Lavanoux had written a letter to Mills telling him that he’d been contemplating the idea of a chapel on the moon. “Your dream church might well be on the same wavelength,” he wrote. After reading Asimov’s article, he wrote to Mills again, telling him that the upcoming issue of Liturgical Arts would be devoted to the idea of a lunar chapel and asking him to draw up blueprints. “There are so few who can see ahead, with vision and imagination!” he told Mills. A few months later, Mills sent back a design for a teepee-like underground structure walled with translucent plastic. At its apex, a solar eye would poke up through the moon’s crust, allowing worshippers to gaze up at the stars.

Around the same time, Lavanoux met a young composer named Johannes Somary. They were both members of the Quilisma Club, a group of Gregorian-chant enthusiasts who met and sang at an apartment in midtown Manhattan. (A quilisma is a musical notation used in Gregorian chant.) Impressed by Somary’s compositions for the group, Lavanoux wrote to Somary in August 1967, telling him about the chapel project and proposing “something like a Hymn to the MOON” in its honor. He wrote, “NOW—the question is: Would you be willing to enter the spirit of this MOON project and compose something of the sort?” He asked Somary to meet him for lunch that Friday to discuss the matter.

*

Johannes Somary was my high-school music teacher. He is a gruff but gentle man now in his seventies, with a heavy Swiss accent and an affectionate disdain for the New World. “Excellence alone!” was his motto. He taught the glee club to sing Bach and Handel, and his answering machine invited callers to “leave a message at the high D.” When he first told me the story of the chapel on the moon, I was in my junior year, and we were at his house in Riverdale, New York, in a study littered with old records and tattered music scores. When I asked him recently to retell the story in more detail, he described his meeting with Maurice Lavanoux that Friday. “It was a lunch at which we consumed an enormous amount of alcohol, in the days when one took two martinis before lunch, or, as I did, a Bloody Mary or two,” he recalled. That day, Lavanoux commissioned Somary to write a song for the chapel’s dedication ceremony. The sheet music would appear in the upcoming issue of Liturgical Arts. But there was a catch. Lavanoux asked Somary to promise that the anthem would not be played anywhere on Earth before its premiere on the moon. “Nobody was giggling about anything,” Somary told me. “It was just a matter of time.” He was given a check for five hundred dollars and told to write a piece having “something to do with the heavens.” As a precaution, the orchestra would need to be small enough for easy transport into space. (No tubas.) “I was the envy of a lot of other composers,” he said. “How did I get this magnificent commission?”

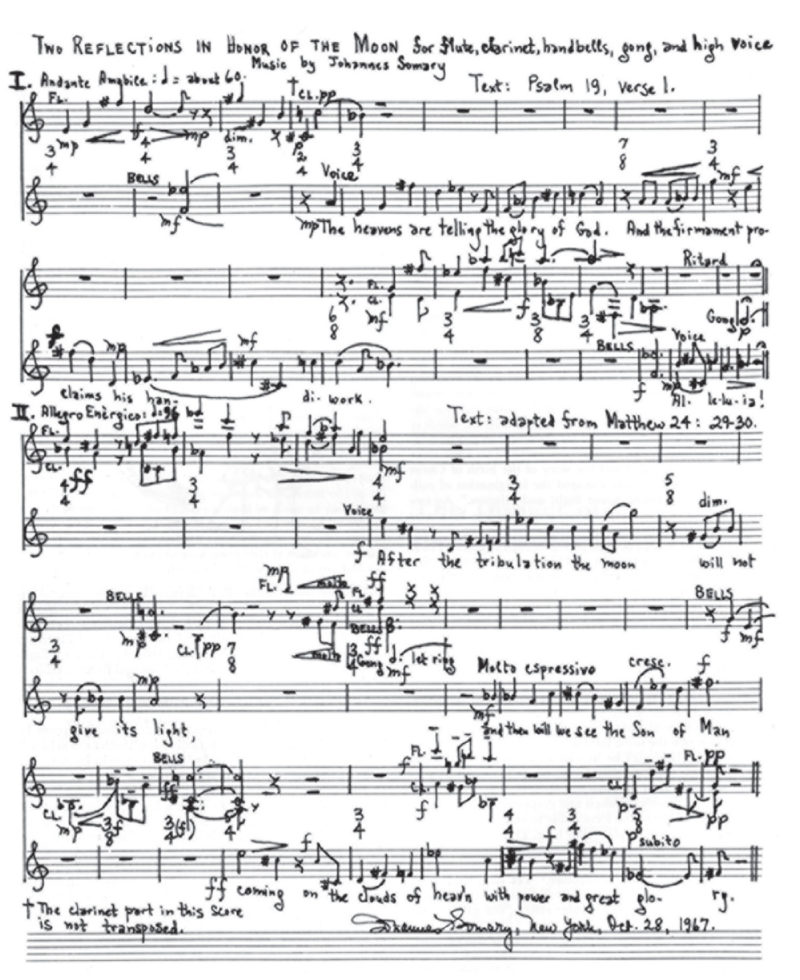

Somary wrote the anthem in two parts and titled it “Two Reflections in Honor of the Moon.” He based the text on selections from the Gospel according to Matthew and Psalm 19. (“The heavens are telling the glory of God; and the firmament proclaims his handiwork. Alleluia!”) The music was atonal—an appropriately forward-looking choice. “If you talk about life on the moon,” Somary said, “you certainly want to get past the conventional language of triads and seventh chords.” He orchestrated the arrangement for flute, clarinet, handbells, gong, and one presumably adventurous soprano. “There would be difficulty finding the right kind of air for a flute player to blow into a flute, or the kind of air that makes it possible for a soprano to sing and be heard,” he said. “I was only concerned peripherally.”

The sheet music appeared in the November 1967 issue of Liturgical Arts, alongside a liturgy for the moon, pictures of space shuttles, the design for the chapel, and a photograph of a specially made “crucifix for the chapel on the moon,” constructed out of welded car bumpers. Lavanoux also reproduced an illustration from the Asimov article, which showed an artist’s rendering of a subterranean lunar colony—a web of structures connected by crystalline walkways, with people in shorts and T-shirts zooming around on mechanized wings. In place of one of the buildings, Lavanoux added in a picture of the cone-shaped chapel.

“Out of man’s dreams of the possible emerge the realities of to-morrow,” Lavanoux wrote in his editor’s note. “The fantastic speed with which man has reached limitless outer space may leave us bewildered and fearful of all the implications inherent in the exploration of the unknown. Yet the known of today was the unknown of the recent past. Those of us ‘over thirty’ can think back to the discovery of electric light, the telephone, the radio (the crystal set), the airplane, radar, television, and now photographs from the moon, via a man-made machine. In this context of history all these inventions are but the continuity of man’s genius, inventiveness, and insatiable curiosity.” He continued, “In the near future man will set foot on the moon. Armed with data now being gathered there and the thousands of photographs sent back to Earth it is within the realm of possibilities that man may establish a colony of earthlings capable of living on the moon, or under its crust, for a limited period. When this time comes the thought of a chapel on the moon is not an outlandish one.” He set the target date at 2000.

*

Lavanoux was not alone in his enthusiasm. Moon mania may have peaked in 1969, with the Apollo 11 landing, but the historical moment that preceded it was a fertile one for the imagination. Anything could happen, and would, the thinking went. Once Neil Armstrong walked on the lunar surface, the space program began to focus on more modest goals, and visions like Maurice Lavanoux’s faded into the ether of dreams deferred. It’s tempting to dismiss the moon-themed issue of Liturgical Arts as a relic of mid-century naïveté. But when it comes to the stars, the tendency will always be to think big. In 2004, George W. Bush announced an ambitious plan to send astronauts back to the moon by 2020, and, in 2007, NASA said it hoped to send a manned mission to Mars by 2037. By 2057, a NASA administrator told the papers, “We should be celebrating twenty years of man on Mars.” So someone’s going to have to think about flutes.

The portrait Somary painted of Lavanoux was one of an intoxicated dreamer, someone who felt the call of the heavens and longed to answer it. Susan J. White, who wrote a book about the Liturgical Arts Society called Art, Architecture, and Liturgical Reform, gives a slightly more tempered description. “Maurice Lavanoux was a man of wide and diverse interests, and always believed that investigations at the periphery of church-architectural matters would surely stimulate and reinvigorate the center,” she wrote to me in an email.

“Did he get ‘carried away’?” she went on. “Well, yes and no. He was certainly a perpetual enthusiast and optimist, believing that if only good minds and hearts could be gathered together and dedicated to a project it would be realized.” But White was hesitant to depict Lavanoux as an eccentric. “Did he believe a ‘Chapel on the Moon’ would ever be built? I think he imagined that if people of the future colonized the moon their religious needs would have to be met, and who better to shape the religious buildings for that purpose than those who had thought long and hard about the question.”

As it happens, the chapel never got built. A few years later, Lavanoux, who had been keeping Liturgical Arts alive with very little assistance, felt his energies diminish. He hoped that a successor would ride to the journal’s rescue, but no one did, and the magazine folded. Lavanoux passed away in the mid-’70s. The anthem, meanwhile, remained unsung. Eventually, Somary and his wife “had a good laugh” and framed the sheet music as a memento. For the past three decades, it has occupied a small spot on the wall of Somary’s study, where it is partially obscured by a bookcase. Somary, meanwhile, stuck to his end of the agreement: the song has never been played on Earth. He has since conducted in more than twenty countries around the world, in venues that include Notre Dame, St. Peter’s Basilica, and Carnegie Hall. But his lunar debut remains indefinitely postponed.

“At least I got paid,” he said. “And I did cash the check.”