“Him Chuck Me First.”

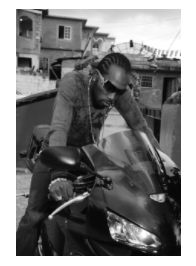

On Boxing Day—December 26, 2003—just as the sun was rising over the town of Portmore, Jamaica, the dancehall deejay known as Vybz Kartel (a.k.a. Adidja Palmer) took the stage at Jamaica’s legendary Sting music festival. The annual concert, widely promoted as “The Greatest One-Night Reggae Show on Earth,” usually includes the most visible artists in dancehall music, and has developed a reputation for hosting infamous onstage clashes between feuding deejays (a term in reggae which refers not to “disc jockeys” but to MCs).

His entourage surrounding him, Kartel dropped maniacal taunts about “wartime” and how “lyrics win war.” Halfway into his set, he launched into the hits: “Gun Clown” and “Buss Mi Gun Like Nutten,” hype tracks that spout the same brutal lyrics popularized by gangsta rap. But Kartel’s songs weren’t just vague anthems to violence; they were weapons aimed directly at Kartel’s rival, Ninjaman (a.k.a. Desmond Ballentine), a senior deejay known for his criminal record and a history of onstage clashes. Kartel called Ninjaman a crackhead, dug into him about some sexual-abuse allegations (“Him say him a bad man and a beat up woman and baby. Then if you beat up lady, that mean to say you a lady bad man and if you beat up baby that means you a baby bad man”), and then accused him of sodomy.

Ninjaman took the stage wearing a graduation cap and gown (a visual jab about being in a higher “class” of deejay than Kartel). But Kartel was a local favorite, and after his strategic set of hits mixed with cheer-induced disses, he’d pulled the twenty thousand fans to his side. Ninjaman gave it his best shot, but after a minute of booing and bottle-flinging, Kartel returned to the stage.

Then something happened that wasn’t supposed to happen: Ninjaman gave Kartel a hard shove on the shoulder—though differing accounts dispute who shoved whom first. (Ninjaman claimed, “Him chuck mi first, mi chuck him back.”) Within a few seconds a fistfight was under way. Kartel and his crew threw Ninjaman to the ground and stomped on his ribs until a few security guards intervened. It was the first incident of onstage physical violence in the Sting festival’s twenty-year history.

Bounty Killer, a then-ally of Kartel’s who was scheduled to perform later that day, canceled his appearance in protest. The crowd didn’t like this. Mobbing fans overtook the bar, attacked each another with rocks, and fired their guns into the air (a common dancehall show ritual). The Jamaica Gleaner reported: “Patrons in the VIP section of the crowd hid under the stage, sheltered behind buses...

You have reached your article limit

Sign up for a digital subscription and continue reading all new issues, plus our entire archives, for just $1.50/month.

Already a subscriber? Sign in