On the perfect spring morning of May 21, 1933, a gaggle of well-wishers and reporters gathered at Stag Lane Aerodrome, just north of London, to see a pilot off on an epic flight. In the excitement of his departure, he headed down the runway in the wrong direction, with the wind rather than into it. The crowd watched his tiny biplane lurch across the grass as it struggled to gain enough speed for takeoff, its wings flexing as if trying to lift off like a bird. Only at the very last moment did it finally claw its way into the air. This inauspicious start must have left those present wondering if they would ever see Maurice Wilson and his plane, Ever Wrest, again.

Two years later, British climbers approaching the foot of Mount Everest’s North Col found the body of a man dressed in a mauve pullover and gray flannel trousers sitting by the tattered remains of his tent. He had been deep-frozen in the process of removing his boots. They guessed immediately that this was Maurice Wilson, reports of whose death on the mountain had been circulating since the previous year. After recovering his diary and some other effects from his pockets, the climbers buried his corpse in a crevasse. Eric Shipton, one of those present, wrote: “Where we tipped it in, it completely disappeared. There was no hole where it fell. Just plain white snow.”

In the years since, Everest has become a vast mortuary where climbers step over their fallen predecessors on their way to the summit, but for these men the discovery of the body of a fellow countryman in this remote and hostile place was still a shock, and cast a pall over the group that evening as they huddled in their tents, taking turns reading from his diary.

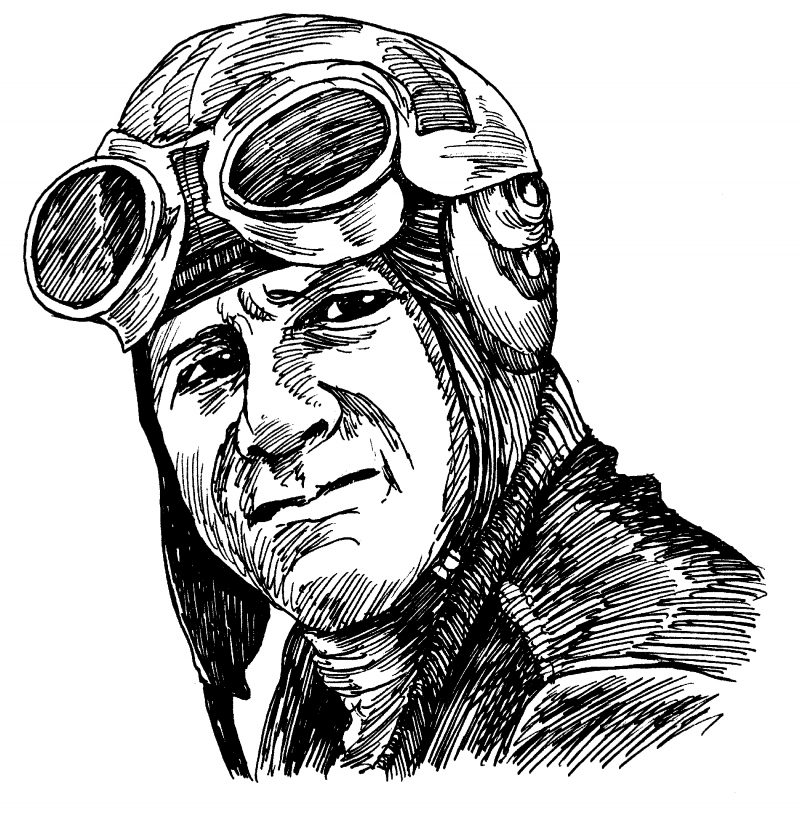

Wilson’s was not the only, nor the most famous, corpse on Everest. The British expeditions of the early 1920s had been dogged by ill fortune. In 1922, seven Sherpas had been swept away by an avalanche, and in 1924 Andrew “Sandy” Irvine and George Mallory had disappeared during their bid for the summit. But where Mallory has become the object of an almost cultlike following, Wilson has been relegated to a humorous footnote in the history of Everest, forever known as “the Mad Yorkshireman.” Mallory was an elegant figure, much admired by the Bloomsbury set for his good looks, easy charm, and breeding; Wilson was a tall, blunt man with doughy features, from a stolid, respectable Yorkshire family that made its living managing textile mills in Bradford. Where Mallory was a fine mountaineer with a laconic turn of phrase, Wilson attempted to climb Everest without any training, relying instead on a strange, mongrel creed of “faith and fasting,” which he would talk about with the fervor of a crackpot evangelist. And yet the paths that led them to their deaths on the roof of the world began from the same place: the inferno of the Western Front.

*

In his book Into the Silence: The Great War, Mallory, and the Conquest of Everest, Wade Davis explores the strange and intimate connection between the battlefields of Flanders and the British expeditions to Everest of the 1920s. The majority of the climbers on these expeditions, Mallory included, had fought in the trenches. They were irrevocably changed by this experience, acutely conscious that their survival was a statistical anomaly where so many of their comrades had fallen. For some of these veterans, climbing Everest came to represent a chance at redemption, a pure and noble endeavor after the corruption of the war. For Mallory and others like him, the war had brought a terrible intimacy with death, which they sublimated into a total commitment to climbing that shocked older climbers, still wedded to the prewar, “gentlemanly” traditions of mountaineering.

Maurice Wilson’s decision, in 1932, to climb Everest alone was also rooted deeply in his experience of the trenches, and reflected the suppressed psychological trauma that, more than a decade after the closing of hostilities, still hounded veterans. Born in Bradford in 1898, Wilson was destined to follow his father into the family textile business—until the war intervened. He enlisted on his eighteenth birthday, in 1916, and reached the front line in time for the bloody quagmire of Passchendaele, the battle that A.J.P. Taylor called “the blindest slaughter of a blind war,” where the bodies of the dead were used as stepping stones and the rats grew fat on human flesh. Wilson fought bravely, winning a Military Cross for single-handedly holding his position against a fierce enemy assault, after all those around him were dead. A few months later a burst of machine-gun fire ripped through his arm and chest. He was evacuated, close to death, and although he recovered from his wounds and served with his regiment as a captain until the armistice, he was left with a weakened left arm that would give him pain for the rest of his life.

The end of the war found Wilson unwilling or simply unable to return to his old life in Bradford. Like many veterans, he would have felt disconnected there from those who had not served in the trenches, separated from the rest of society by what the poet Herbert Read described as “a great screen of horror and violation,” which left veterans feeling “like exiles in a strange land.” This perhaps exaggerated an already solipsistic cast to Wilson’s character, so that he became an isolated, curious figure who drifted around the globe during the 1920s, spending time in America before washing up in New Zealand. After stints as a farmer and salesman of patent medicine, by 1930 he had used his family background in the textile business to establish a successful dress shop in Wellington. By this time he was also on to his second marriage. But there remained within him a great dissatisfaction and restlessness, and when this marriage began to crumble as well, he found himself drawn back to England.

He settled in London, cushioned by the substantial proceeds from the sale of his business. While trying to buy a car, he struck up a friendship with the salesman, Leonard Evans, who then introduced Wilson to his pretty and vivacious wife, Enid. Together, the suburban couple and oddball traveler formed a curious and innocent ménage à trois. Afternoons spent at the Evanses’ small house in Maida Vale, a suburb of London, became one of the steadying poles of Wilson’s existence. But, displaying what we would now see as the symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder, Wilson was soon overwhelmed by a deep sense of spiritual exhaustion and depression. When he fell ill, wracked by a cough that seemed to signal the onset of tuberculosis, he suffered a nervous breakdown.

Temperamentally unable to submit himself to the authority of conventional medicine or religion, Wilson turned to a faith healer. This mysterious figure, whom Wilson never named, lived in a luxurious flat in Mayfair and expounded a philosophy based on faith and fasting that, he claimed, had saved him when doctors had given him only three months to live. He instructed Wilson to fast for thirty-five days in order to purge himself of “all extraneous matter physically and mentally” and to put his faith in God. Wilson retreated to his lodgings to await enlightenment, withdrawing even from the company of the Evanses, to whom he wrote: “I must shake this thing off. If I come back you’ll know that I am all right. If you don’t see me again you’ll know that I am dead.”

Wilson’s willingness to follow this extreme regime, fasting until he lay “close to death,” so that he was “ready to be born again,” revealed in him a need to abandon himself to a single, all-consuming course of action. He emerged thinner, weaker, but convinced he was cured. Now, with the fervor of the convert, he became determined that the whole world should benefit from this creed of faith and fasting.

As part of his convalescence Wilson went on holiday to Germany’s Black Forest in the summer of 1932. In a café in Freiburg he came upon an old newspaper clipping with an account of the 1924 Everest expedition. In the tragic deaths of Mallory and Irvine, Wilson saw an opportunity. There could be no better proof of the power of faith and fasting than if he, a man with no mountaineering experience, could climb Everest alone. Wilson became convinced that, with his spirit and body cleansed, he could achieve the prize that had eluded the greatest climbers of the age and their large, military-style expeditions.

There had been a hiatus in British expeditions to Everest after 1924, due in no small part to the profound sadness felt at the deaths of Mallory and Irvine by a nation still reeling from the loss of so many of its young men. Political relations between Tibet and British India had also cooled to the point that officials in Lhasa refused to contemplate another Everest expedition in 1925, and they remained frosty until the end of the decade. By the early 1930s, however, the eyes of Britain and its empire had turned once again to the highest mountain in the world, which the press had dubbed “the Third Pole.” British officials began to pressure the Tibetan government into allowing fresh attempts at the summit. These officials believed that even if Everest did not lie strictly within the boundaries of the Empire, it lay within its sphere of influence, and they jealously guarded what they saw as the British right to be the first to conquer it. The success of their diplomacy became evident with the announcement of an expedition planned for 1933, to be led by Hugh Ruttledge.

However, it was not the Ruttledge expedition that caught Wilson’s eye. British diplomats had also been at work persuading Nepal, a closed kingdom like Tibet, to allow the aircraft of the Houston-Westland expedition to fly from Purnea, in northern India, through Nepali air space to Everest. This expedition, funded by the eccentric former showgirl and millionairess Lady Houston, was to attempt the first flight over the mountain. Wilson impulsively concocted a plan to hitch a ride on the wing of one of the expedition’s lumbering Westland biplanes, parachute onto the mountain’s upper slopes, and from there make a bid for the summit. There is no record of Wilson trying to put this improbable plan into action, and it is unlikely that it was ever more than a daydream. But from this point, flying and Everest became intertwined in his mind.

Airplanes and aviators were everywhere, in the news and often directly overhead. On his visits to the Evanses in Maida Vale, Wilson could not have ignored the swarming racket of the little yellow planes of the London Aero Club, based at the nearby Stag Lane Aerodrome. The war had transformed planes from primitive, underpowered box kites into fast and relatively reliable craft. It had also produced a generation of military-trained pilots who, perhaps surprised at their survival in the face of such terrible odds, pushed themselves into public consciousness with their record-breaking flights and barnstorming antics. This in turn sparked a craze for amateur aviation that, encouraged by the development of relatively inexpensive planes by manufacturers like de Havilland, reached its zenith in the late 1920s and early 1930s.

A man who was as determined as Wilson was to make his mark on the world was unlikely to have missed the example of pilots like Amy Johnson. Johnson had left her Maida Vale flat to take off from Stag Lane for Australia in 1930. She discovered that her tiny biplane not only lifted her from the ground into the sky but also from a humdrum life into a new world of celebrity. When she returned falteringly to earth, she was greeted by cheering crowds, clamoring reporters, and local dignitaries acclaiming her feats for the empire.

The fierce individualism of the record-breaking pilots with their often-transparent desire for fame offered an appealing model for a solitary character like Wilson, one that mountaineering, with its dependence on large, hierarchical expeditions tied to national concerns, did not. And while the mountaineering fraternity was a closed one, restricted to an upper-class elite, flying was a modern, democratic pursuit, open to anyone prepared to scrape together the modest fees for flying lessons. It was therefore in perfect alignment with a society that, like Wilson, had lost its reverence for the old class structures as a result of the war.

When Wilson returned from Germany he went out for a night on the town with the Evanses. After dinner at a restaurant in Mayfair and dancing at a nightclub, they returned to the couple’s house, where, at four in the morning, the excited Wilson sketched out his plan: he would fly from London to India, and then on to Everest, where he would crash-land on the lower slopes before climbing the highest peak in the world. When his friends demurred, raising the obvious point that he was neither a mountaineer nor a pilot, they recalled that Wilson replied: “Now I believe that if a man has sufficient faith he can accomplish anything… I’ve got a theory to prove and I intend to try and prove it.”

Wilson set about realizing his delusional plan with the fastidious care that, in another life, he might have brought to organizing a driving holiday to France. He bargained hard for a secondhand Gipsy Moth. This diminutive biplane was manufactured by de Havilland in its factory at Stag Lane. It had been designed for the enthusiast market and had delicate, fabric-covered wings that could be folded back to allow it to be towed behind a car. With its fine Roman nose, it looked too fragile for the arduous journey that Wilson planned, but in the hands of determined aviators like Amy Johnson and Francis Chichester, it had proved a willing and dependable craft. Wilson named his plane Ever Wrest.

Wilson began his flying lessons at Stag Lane. Nigel Tangye, his instructor, quickly realized that his clumsy pupil would never be a great pilot, but Wilson’s dogged determination meant that he soon gained his solo flying license. Wilson became a constant presence in the sky above London, putting in hour after hour to become a workmanlike, if inelegant, pilot.

When he wasn’t in the air, he was busy with preparations for the journey. He studied maps to plot his course for India and accounts of the Everest expeditions for routes up the mountain. Digging deep into his savings, he began buying equipment that he proudly showed to the Evanses in their living room. He bought the “improved” sleeping bag and tent that had been designed for the Ruttledge expedition, a tweed climbing suit lined with silk to keep out wind and snow, boots insulated with cork from heel to toe, a custom lightweight oxygen rig, a small Union Jack to plant on the summit, and a height recorder and a compact camera with an automatic shutter to prove he had made it there.

He became a familiar, if inscrutable, figure at the London Aero Club, always happy to lecture his fellow members on his plans when asked but with little interest in small talk. From the deck chairs lined up in front of their modest clubhouse, they watched as he strode around the perimeter of the airfield in his hobnail boots, using any time he was grounded by the weather to build up his fitness. To this end, a number of times he also walked the two hundred miles to Bradford to visit his family. He fasted regularly and monitored his diet zealously; offered a beer by Tangye, he said: “I don’t need a drink. I’m an apple-and-nuts man!” He made an illegal parachute jump over London “just to test my nerve.”

What these preparations did not address was his lack of climbing experience. He made brief visits to the Lake District and the Welsh mountains to do some hiking and a little scrambling, but he never tried to learn even the basic techniques for climbing on snow and ice. If Wilson’s ignorance of the conditions of high-altitude climbing now seems unthinkable, it must be remembered that at that time the high Himalayas were less familiar than the surface of the moon. It was not until after Wilson’s departure, when the Houston-Westland expedition published its photographs, that the first aerial images became available. The only accounts available of Everest were from the expeditions of the 1920s, and they were written with the radical understatement of a British gentleman, a terse code that had been perfected during the war, where an upcoming bloodbath could be referred to as “a show.” This would find its ultimate expression in Mallory’s famous response to the question of why he wanted to climb Everest: “Because it’s there.” But there was also a failure of imagination in Wilson. With no feeling for the mountains, no sense of awe for the high places, Wilson regarded Everest as just another hill, different from those he had encountered in Yorkshire only by virtue of the fact it kept going until it touched the sky. All that was required of him was to be fitter, more determined, and more faithful than the upper-class twits, weighed down by the baggage of their massive expeditions, who had failed before him.

Most of all, Wilson was filled with an impatience that precluded the painstaking accumulation of skills and knowledge of a mountaineering apprenticeship. In his late teens he had been picked up by the bloody wave of history that, after it receded, had left him stranded, unsure where he should go or what he should do. Now, more than a decade later, and with the acute sense of mortality that only a survivor of those terrible battlefields could possess, he felt that time was running out; he wanted to reconnect with the pulse of history; he wanted something to happen. With the sentimentality of a man who lived more on feeling than thought, he planned his departure for the day of his birthday, April 21, 1933.

By now the British press had caught wind of Wilson’s plans. It appraised him with a wary eye. On the one hand, authoritative voices described his attempt as folly, and Wilson himself often cut an absurd figure. On the other, Amy Johnson and her peers had proved not only that ordinary individuals could succeed against enormous odds, but that there was great public interest in these new, democratic heroes. Wilson himself proved a willing interviewee, eager to promote both himself and his creed.

If the press never fully discounted his attempt, its coverage brought with it another kind of attention. On hearing of his plans to fly over the forbidden kingdom of Nepal, the Air Ministry wrote to Wilson, pointing out that the Houston-Westland expedition, which had successfully completed its flight over Everest on April 3, had required lengthy diplomacy to obtain clearance to fly through Nepali air space. It was very unlikely that he would receive the same permission from the Nepali government. Wilson, with his instinctive dislike of authority, began an ill-tempered correspondence with the Ministry that resulted in him receiving, shortly before his departure, a letter informing him that the colonial authorities in India were not prepared to approach the Nepalese on his behalf. Therefore, under no circumstances would he be allowed to fly into Nepal. Relishing the role of the underdog, he told reporters: “The gloves are off. I’m going on as planned. Stop me? They haven’t got a chance.”

Wilson’s departure had been delayed first by illness and then by an experience common to early pilots: he had crashed on a flight up to Bradford to see his family, coming to rest upside down in a field. This did not stop him. Ever Wrest was quickly repaired and his departure rescheduled for May 21. Leonard and Enid Evans and other well-wishers assembled to bid their farewells. Glamour was added to the occasion by the appearance of Jean Batten, the New Zealand aviator known as “the Garbo of the Skies,” who was keen to be captured by press photographers sending a fellow pilot on his way. Before Wilson took off, Enid tied a mauve ribbon to one of Ever Wrest’s struts for luck, while Wilson produced a red-and-white silk pennant, which he asked friends to sign to make a “flag of friendship” which he promised to plant on the summit of Everest. Before that, however, he would have to fly five thousand miles over often-barren and forbidding territory, with only two hundred hours of solo flying under his belt.

Yet in many ways Wilson proved ideally matched to this task. The pilots of these early years of aviation spent their record-breaking flights hunkered down in their cramped cockpits, protected from the elements only by a small Perspex windshield. Unable to remove their feet and hands from the controls, they spent the hours cursing the deafening and remorseless roar of the engine, all the while dreading the moment when, with what Antoine de Saint-Exupéry described as a “great rattle like the crash of crockery,” it might come to a sudden stop, the shocking silence that ensued broken only by the sound of air rushing past as they dropped to earth. They were at the mercy of the weather’s caprices. Sudden updrafts might flip their delicate machines over, or clouds might smother them so completely that they would fly through an eerie, cotton-wool world devoid of all sensory cues until they plowed, unsuspectingly, into the side of a mountain. Under these conditions, what often made a successful pilot was simple determination. And this Wilson had no shortage of.

Wilson also proved to be an excellent navigator, keeping an eye on the compass in his cockpit and peering over the side of his plane at the land and sea stretched out below him. His route on the first day took him over the British battlefields of the Western Front, which were still clearly visible from the air, pockmarked and furrowed like the surface of a desolate planet, and fringed by constellations of white crosses marking the graves of the fallen. He then followed rivers and roads south through Europe, before hugging the coast from the Riviera down to the heel of Italy and then across the Mediterranean to Tunisia. He made a series of hops along the barren, uninhabited North African coast, from one dusty, desolate, heat-soaked airfield to the next—Bengasi, Tobruk, unfamiliar names that had yet to take their turn on the world stage—where the fuel was often dangerously contaminated and the local officials less than welcoming to the dazed, half-deafened pilot.

By the time he reached Cairo, his face burned brick red and seamed with oil and dirt, Wilson must have felt a growing confidence in his abilities—if he had ever had any doubts. But here the Air Ministry caught up with him. His plan had been to continue across Persia, which, like Nepal, required a permit to fly through its air space; unlike Nepal, however, Persia was under British jurisdiction, and Wilson was informed by British officials that one would not be forthcoming. If he landed to refuel—which he would have to do—he would be arrested. Wilson flew on to Baghdad, a thousand miles in a single day over high, featureless desert, in the hope that he would persuade officials there to give him the permit. The story was the same: nothing doing, old man. He fell into a conversation with British military pilots and crewmen at the airfield, and with their connivance blocked out an alternate route avoiding Persian air space, via Bahrain and the Persian Gulf.

The seven-hundred-mile flight from Baghdad to Bahrain was approaching the limit of Ever Wrest’s range even with the extra fuel tank that filled its second cockpit. It would mean nine hours of nonstop flying, stuck in the cramped confines of the cockpit, feet and hands glued to the controls, in the burning Arabian heat. Wilson did not hesitate and completed the flight in his usual businesslike manner. In Bahrain he was again obstructed by a British official who refused to give Wilson a permit to refuel unless he promised to turn back. Wilson gave his word, refueled, and took off the following morning, only to wheel lazily around above the airfield and head off in the opposite direction, on course for India.

His flight from Bahrain to Gwadar, in India, was, at 770 miles, at the extreme limit of his range. Of the nine-and-a-half-hour flying time, five hours were spent following a compass bearing over the featureless waters of the Persian Gulf. Any diversion from his true course would have been fatal. So, too, would have been any mechanical failures in an aircraft that was in desperate need of an overhaul. As he held his plane steady for hour after hour, low over the blinding sea, anxiously listening to each change in the engine’s note and watching the slow, almost imperceptible sweep of the fuel gauge’s needle, Wilson passed beyond the borders of the world of cause and consequence and into one governed solely by faith. He landed at Gwadar as the sun was setting, with barely enough fuel to cover the bottom of his tank.

By reaching India, Wilson had made his crazy plan suddenly seem less crazy. If he had managed the enormous feat of flying five thousand miles, then perhaps, just perhaps, he might climb Everest. As he made a series of gentle hops across India to Purnea, the airfield that the Houston-Westland expedition had used for Everest, he was met at every stop by reporters eager to hear his plans. Buoyed by this attention, Wilson was in garrulous form, telling the Daily Express on June 9, 1933:

Enough rice and dates to last fifty days will be in my rucksack when I begin to climb Everest after landing on the mountain 10,000 feet up. One trained man can succeed where a large group has failed.

Displaying an uncharacteristic awareness of what others might think of his plan, he concluded:

There is no stunt about it. Mine is a carefully planned expedition, which is certain of success, although the orthodox mind may consider it madness.

What “the orthodox mind” thought of his experiments with diets and fasting goes unrecorded: “The best procedure is to take one meal a day, which will enable me to breathe down to my stomach, taking in a vastly increased supply of oxygen.”

On arrival in Purnea, however, he was again informed by British colonial authorities that there was no hope of him receiving permission to fly over Nepal. This, like so many of the decisions by officials in relation to Wilson’s quest, was a result both of simple diplomatic realities and, if not concern for then at least disquiet at this strange figure who seemed determined to kill himself. They impounded his plane, releasing it only when he pledged not to try to complete his plan. A crestfallen Wilson began a series of short, haphazard flights across India, until he was compelled by his dwindling funds to sell Ever Wrest, which had begun to deteriorate in the humid conditions of the approaching monsoon. Wilson took the train to Darjeeling, where he booked into the Albert Hall Hotel, to all appearances just another holidaying British sahib.

Wilson’s progress through India had been carefully monitored by the colonial authorities, and it did not escape their attention that this hill station, which on a clear day offered a spectacular view right into the heart of the Himalayas, had been the starting point for every expedition to Everest. Local officials were ordered to keep a close eye on him, and to place restrictions on his movements by refusing him permits for trekking.

They were right to be suspicious. With the onset of the monsoon season, Wilson knew he had missed that year’s climbing season, but he also learned to his relief that the Ruttledge expedition had failed to conquer Everest. He wrote in a letter:

In view of all the hold-ups doesn’t it seem to you somewhat uncanny that I am as optimistic as ever about my job of climbing Everest; the one I’ve been given to do?

Over the winter of 1933 to 1934 he schemed with his usual diligence to complete his plans. Realizing that he would never be issued the necessary permits to trek to Everest, Wilson quietly hired three Sherpas—Tsering, Rinzing, and Tewang—who had worked on the Ruttledge expedition the previous summer, and together they plotted his illicit departure. In the early hours of March 21, 1934, Wilson slipped out of his room, for which he had paid six months in advance to allay the suspicions of those watching him, to meet up with his Sherpa companions on the outskirts of Darjeeling. In the bright moonlight he cut a strange figure. He wore a fur-lined cap with large earflaps, a waistcoat brocaded in gold, a twelve-foot sash of red silk wrapped around his waist, and a heavy woolen mantle of navy blue. This was Wilson’s plan: to travel disguised as a Tibetan holy man with the Sherpas as his entourage. As an added precaution, the party would travel only by night; however good his disguise, Wilson’s six-foot-one frame could bring only unwelcome attention.

The three-hundred-mile trek that Wilson was undertaking was an arduous one. First, traveling by night, they entered Sikkim, where they threaded through the lush forests and steep-sided gorges of the subtropical foothills before entering the forbidding world of the high Himalayas, crossing passes of over twelve thousand feet. On March 30, they crossed into Tibet, where Wilson divested himself of his disguise, and they began to travel openly during the day, sure that they were beyond the reach of the British authorities. Here they came to the stark, forbidding moonscape of the roof of the world. With his three companions and a single, often-recalcitrant pony to carry supplies, Wilson moved swiftly, traveling far lighter than the British climbers who had preceded him, with their unwieldy caravans of porters.

The diary recovered from Wilson’s pocket begins on the day that he left Darjeeling. His entries during this long journey read like those of any other trekker, by turns exhilarated and exhausted, at one moment exclaiming at the beauty of butterflies and at another deploring the harshness of the weather, and—most of all—obsessed with food. The ascetic fasting enthusiast, the “apple-and-nuts man,” spends much of his time carefully listing what he has eaten each day. He refers to Quaker Oats by name almost as many times as to Everest itself.

Now kept in the Alpine Club’s London library, Wilson’s diary is an uncanny object, given by its proximity to its author’s death the aura of a saintly relic or a memento mori. It is also an infuriating document, Wilson’s cramped handwriting made all the harder to read by the second-generation photocopy that a researcher must work from. Each indecipherable word takes on an occult charge, as if it contained the key to Wilson’s strange and terrible journey. But, of course, the diary is not a window directly into his soul. Occasionally, his grim obsession bursts through:

Don’t get the slightest kick out of the whole adventure as already planning the future after the event. I must win.

At other moments, he is giddy with the possibility of success:

What a game: maybe in less than 5 weeks the world will be on fire.

The diary is addressed to the Evanses, and he often refers with great sentiment to “their golden friendship.” It is perhaps significant that he uses the letter E to refer to both Everest and Enid. In one entry he playfully pretends to mix the two up:

Isn’t she a darling? She’s magnificent—Not you. The ruddy mountain, I mean.

At another point he notes “[o]f course I’m writing all this to Enid” for “she’s been the golden [rod] from the start.” (Yet again the diary obscures a crucial moment—the word rod is illegible, a guess on my part.) Wilson’s two failed marriages suggest that, perhaps as a result of his traumatic war experiences, he found it difficult to maintain close relationships. In the married Enid he seems to have glimpsed the possibility of the love he never had. It may be crude to equate this desire for an unattainable woman with his obsession with Everest, but both seemed to emerge from deep wells of isolation and loneliness within him.

After twenty-five days, the party arrived at the Rongbuk Monastery, a collection of low stone buildings fronted by a large, lopsided stupa, set in a bleak valley over which the vast, blunt pyramid of Everest loomed. Confronted with this view, Wilson wrote with hallucinatory calm:

Everest looks magnificent and am longing to get the job over with after a couple of days lay up.

By contrast, on their arrival at Rongbuk the following year, the experienced climbers who would later find Wilson’s body could express only a shocked sense of inadequacy when confronted by this spectacle of the mountain. From the moment Wilson conceived his plan to climb Everest while sitting in a café in Freiburg, he seemed unable to comprehend the reality of the mountain. Even as it towered over him, he felt no sense of incongruity:

When I look at E. I don’t even get a thrill apart from its magnificent beauty. I just feel part of the scheme and that I should be here by every right.

Oblivious to the hardships that awaited him, Wilson spent two days resting at the monastery. They were a welcome relief from the rigors of the trek. He noted good-humoredly that in his outfit of a mauve flying shirt, green flannel pants, and white tennis shoes, “anyone would think that I was on a picnic.” His party was tired and footsore, but otherwise in far better condition than many of the official expeditions, whose members often reached Rongbuk plagued by illness and the grinding effects of altitude. Wilson seemed indestructible.

Wearing his white flying helmet “for effect,” he visited Dzatrul Rinpoche, the abbot of the monastery. With his often-disarming openness, Wilson told Rinpoche that he “had travelled the world and never felt so happy in anybody’s company before.” The abbot, who had first come to the valley to live as a hermit in a cave, for his part would speak warmly of Wilson to the climbers who arrived the following year. The large climbing parties of the early 1920s had been a great nuisance to Rinpoche, their presence and ensuing deaths a disturbance to the spirits of the mountain. But where their motivation remained incomprehensible to him, Wilson’s solitary, ascetic quest was one that he could understand.

Two days later, Wilson set off to climb Everest alone, leaving the Sherpas at the monastery. He had staged and restaged this moment in his imagination, and he was always alone. His moment of triumph, when he reached the summit and “set the world on fire,” could not be shared. Not even the brute reality of Everest could challenge this fantasy. The childish self-centeredness of his thinking is captured in a diary entry from that day in which he hopes to reach the summit on his birthday, noting that it “would be a novel birthday present for a man to find himself on top of Mt. E.”

He shadowed the route of the Ruttledge expedition the year before, and made good time to base camp, which sat at the foot of the East Rongbuk Glacier, where he noted confidently in his diary: “19,200 ft up—only another 10,000 feet to go—sounds easy.” But here, at last, he was confronted by an obstacle that was indifferent to his delusional, obstinate determination. He had to travel the length of the glacier to reach the lower slopes of the mountain, and he spent the next two days trapped in the wreckage of buckled ice, lost, like an ant in a vast pile of shattered glass, in its maze of unstable seracs and hundred-foot towers. The high-altitude sun fogged his vision and seemed to bore into his skull. A tormenting thirst dogged him at every step. In his diary he wrote that it had been a “hell of a day” and fretted that he would not be able to make it to the summit on his birthday.

Even after he managed to clear the glacier, his lack of climbing experience continued to hamper him; it was only a fresh fall of snow that allowed him to make any progress without the crampons he had never thought to bring. A note of churlishness enters his diary: “If I’d had loads of coolies like exp[editions] shd have been at Camp 5 by now” and “Think the climbers had it cushy with servants and porters.”

Six days after he had set off, exhausted by his floundering, his “eyes terrible and throat dry,” he fled down the mountain, arriving at the monastery after a delirious, fourteen-hour march. He was greeted in the darkness by the immensely relieved Tewang, “with outstretched hand and row of snow white teeth in a smoky face.”

Wilson spent four days in bed recovering, but the shocking realities of the mountain seemed to slip quickly from his consciousness. Immediately he began to plan his next attempt. He had learned enough to arrange for the Sherpas to accompany him to Camp 3, at the foot of the North Col, but from there he was still determined to continue alone. At the same time as he took this practical step, he continued to fuss over inconsequential details, writing:

Pity I did not bring any dried fruits with me as they would have been a great asset to my diet.

Wilson spent the next three weeks loafing around the monastery, where a festival—“some cheroo,” he called it—was taking place, drawing pilgrims from as far as Darjeeling, and swelling the population of the desolate valley. As he waited first to regain his strength and then for Tewang to recover from illness, he filled his time preparing for his summit attempt by baking biscuits from brown bread and his beloved Quaker Oats (he notes carefully in his diary: “Quaker Oats are a marvelous food”), and scrounging what treats he could from the stores left at the monastery by Ruttledge, including an enormous tin of mint bull’s-eyes. As isolated as if he were on a distant star, he thought of Leonard and Enid in their cozy living room in Maida Vale:

Don’t suppose an evening goes by but you and him speculate as to where I am and what I am doing. Good to think that I shall be with you again in no more than a couple of months.

To relieve his loneliness he spent a day with the Sherpas in their “bungla,” all the while aware that his presence was an imposition on them.

On May 12, the tall Yorkshireman and the three Sherpas departed from the monastery and began to pick their way up the mountain. Wilson, as ever looking for propitious, occult signs, noted that “the date of commencement adds up to a 3.” With the experienced Sherpas as guides, the party made decent progress and, on the fourteenth, arrived at Camp 3, where they plundered a cache left by the Ruttledge expedition. Wilson, all thoughts of fasting swept away, gleefully listed the bounty, the familiar brand names taking on a talismanic quality in this remote, inhospitable place:

Plum jam, honey, butter (I haven’t seen any for 9 weeks), cheese, assorted biscuits, Bournville chocolate, anchovy paste from Fortnum & Mason, sugar, Ovaltine, Nestles milk and other treasures for heaven.

Camp 3 huddled at the base of the ice-and-snow-clad cliffs that guarded the North Col, itself the gateway to the summit. For experienced mountaineers, this was the point at which the real climbing began; it was from here that Wilson planned set out “alone for the final crack.” But first he was trapped in his tent for a week as the weather closed in. On some of these long days, Wilson filled his diary with rambling and good-natured entries; on others he cowered in his sleeping bag with his balaclava pulled over his eyes to escape the tormenting “violet rays” of the sun, which penetrated even the thick blanket he had fixed over his tent.

Finally, on the twenty-first, Wilson set off from Camp 3 for the North Col. Rinzing went with him, giving him a desperately needed lesson in cutting steps through the snow into the iron-hard ice beneath, before turning back in the afternoon. Wilson was alone again on the mountain. For the next four days he struggled in vain to reach Ruttledge’s Camp 4; the terrain was simply beyond his abilities. Even as his strength ebbed away, his sense of being on a mission remained strong: “Funny but all these stink ups and yet I feel I have a reason.”

On the twenty-fifth he retreated back to Camp 3, where the Sherpas were waiting for him. He tried to persuade them to join him for a final attempt, but they refused, rightly understanding that only death awaited them on the mountain. Wilson holed up in his tent. For two days he lay in his sleeping bag, writing only: “Stayed in bed.” As his body began to pool its remaining warmth at its core, beating a retreat in the face of the biting cold and desperate thinness of the air, his consciousness contracted, entering a fugue state peopled by voices and events from his past. On the third day, in a burst of dreamlike lucidity, he pulled the silk flag of friendship from his bag, and, for a moment, he was suffused with a warm sense of companionship: “Strange but I feel that there is somebody with me in the tent all the time.”

On the twenty-ninth he set off for Camp 4 alone. In the moments before they went over the top, soldiers in the trenches were often described as being lost in a trance, like ghosts or sleepwalkers. So, now, was Wilson. All considerations had receded apart from the fatal imperative to keep moving forward. It is impossible to know how far he managed to climb on that day before pitching his tent. His entry for the following day is again: “Stayed in bed.”

On the morning of May 31, Wilson woke to find the inside of his tent glowing with the light of the high-altitude sun. Before struggling from his sleeping bag, he made his last diary entry: “Off again, gorgeous day.”

He emerged from his tent into a world where the void of interplanetary space seemed to press close and the bitter clarity of the atmosphere played cruel tricks, making the distant appear within easy reach. Did his mind return to that remorselessly horizontal landscape through which he had slogged and fought as a young man, where the earth was mixed with the bones of men and the air filled with rain, smoke, and the stench of rotting flesh? Or did he think of that moment when, suspended in the thick, hot air above the Persian Gulf, he passed the point of no return and abandoned himself, ecstatically, to his fate? Or did he see Enid, her familiar smile welcoming him back to the small, warm living room in Maida Vale that he remembered so well? We will never know. This was the day that Maurice Wilson kicked free of the earth.