Photographer Ralph Eugene Meatyard, who was born in Normal, Illinois, in 1925 and died of cancer in Lexington, Kentucky, in 1972, worked his entire adult life as an optician, making lenses for glasses. Though he took and developed thousands of pictures, only a sampling of his work has been published. A slim Phaidon 55’s selection appeared in 2002; Ralph Eugene Meatyard, compiled by writer and critic Guy Davenport in 2004, attempts a fuller account of his entire oeuvre; and, finally, Meatyard’s own The Family Album of Lucybelle Crater, first published in 1974, is a fictional photo album of people wearing costume-shop masks. Meatyard took all of his photographs in and around Lexington, where he moved in 1950 and stayed until his death. In the essay that precedes the photographs in Ralph Eugene Meatyard, Davenport reveals that Meatyard bought his first camera at the age of twenty-five to photograph his first child. But even Davenport, a close friend of Meatyard’s, admits to knowing little of Meatyard’s life before he moved to Kentucky: “There was nothing behind him, nothing at all that one could make out.”

*

In a letter to Jonathan Williams, the original publisher of The Family Album of Lucybelle Crater, Meatyard wrote:

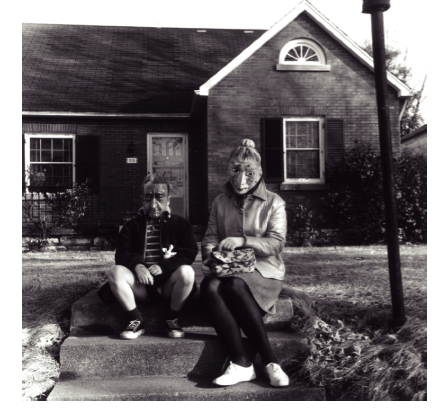

Billboards in any art are the first things that one sees—the masks might be interpreted as billboards. Once you get past the billboard then you can see into the past (forest, etc.), the present, & the future. I feel that because of the “strange” that more attention is paid to backgrounds & that has been the essence of my photography forever.

To a striking degree, houses are in the background of Meatyard’s photographs. Over and over again, houses, either rundown or propped up in middle-class order, stand behind the oddly posed or out-of-focus or masked figures in the foreground. Nearly every photograph in The Family Album of Lucybelle Crater is taken in, or outside of, a house, often Meatyard’s own. And, as critic James Rhem labors to point out in an excellent essay included at the beginning of the Distributed Arts Publishers edition, even when they do not explicitly feature houses, they were often taken just outside them. Davenport and the curators of a landmark 2004 and 2005 show at the International Center of Photography invented the term Romances to refer to these and other Meatyard photographs in which props and masks and awkward poses are employed to transform the “everyday nature of a family photograph into an unexpected moment.” About this body of images, Cynthia Young, in her introduction to Ralph Eugene Meatyard, writes:

But Meatyard’s truly unique vision began to emerge when he started working regularly on photographs of his friends and family. Driving out in the countryside on Sundays, he would suddenly stop the car at some abandoned antebellum mansion to use it as a stage for the performances that would become his photographs.

I did a count of the Romances included in Ralph Eugene Meatyard: 90 of 130 were shot in, or in front of, houses.

*

If you stand across from 901 North McLean Street in Bloomington, Illinois, your back to Franklin Park, and look at the brick house painted gray, you will see two historical markers stuck between the sidewalk and the street. The taller one, regarding Adlai Stevenson, explains that Stevenson was Grover Cleveland’s vice president and Adlai Stevenson II’s grandfather. The second marker commemorates his wife, Letitia Green Stevenson, four-term president general of the Daughters of the American Revolution.

There is not a third historical marker, one that might begin: “Ralph Eugene Meatyard (1925–1972), noted American photographer, lived in this house, off and on, from 1941 to 1950.”

The house at 901 North McLean Street was Meatyard’s sixth home in Bloomington-Normal, two towns that are as seamlessly linked as an amoeba midway through meiosis. The first was at 904 South Fell Street in Normal. By 1928 his family had moved to 1109 South Fell Street, only a couple blocks south of the first house and across the street. According to his grandmother’s obituary, he lived at 209 West Locust Street in Normal—a house that has, in the wake of Illinois State University’s expansion, disappeared. Between 1934, when they went back to live at 904 South Fell, and 1937, when the Ralph R. Meatyard family is listed at 4 Harwood Place, they moved again. By 1940, they had moved back to Fell Street, this time to 304 North. Then, when Meatyard was sixteen or so, in 1941 they moved to 901 North McLean, to the house where Adlai Stevenson and his wife once lived.

In 1942, the year after he moved into this house, Meatyard was a junior at University High School in Normal. He appears in the yearbook once, in a group of five (“C. Holtz,

J. Sage, E. Meatyard, H. Simpson, C. Malmberg”). He stands in the middle, holding a book, in a long-sleeved, collared shirt and dark pants, his hair slicked back with a curl of bangs over his forehead. He is laughing. He is seventeen, maybe eighteen. The next year he will graduate, join the navy, and attend Williams College as a student in the predentistry program. Married, he will move back in with his parents, work at the Gailey Eye Clinic just up the street, and stay until 1950, the year he will move to Lexington, Kentucky.

*

As can be seen, Meatyard moved a lot, and his father changed jobs nearly as often, working variously as a gas station attendant, dairy salesman, and mechanic. But it was his work restoring historic houses that foretold his son’s future photographic interests. As Davenport says in an interview about Meatyard that precedes the photographs in Ralph Eugene Meatyard:

Most of Gene’s portraits of humans, pictures of humans, I should say, are juxtaposed with buildings that are being torn down, or buildings that are in utter disrepair. I spent a whole day with Bonnie Jean [Cox] in White Hall, the utterly ruined mansion of the Kentucky grandee Cassius Clay way back. The building was deplorable; it been lived in by squatters, the walls had been written on…. I know Gene was fascinated by this building; he’d pretty much discovered it on his own. It has been restored now as a tourist attraction. And I am pretty certain Gene would say that they have ruined it by painting the walls and putting the stairs back up. So destruction was one of his themes.

*

All told, I have been to eight houses where Meatyard once lived, or, if they are no longer there, to the lots where they once stood. I have even visited the Meatyard family grave in Bloomington’s Park Hill Cemetery. Once I found myself standing on a dark, suburban street six hours from home, looking for a house that I could not, and never did, find: Meatyard’s final home, at 418 Kingsway, in Lexington, Kentucky. Kingsway, so far as I could ever tell, ends in a cul-de-sac after three blocks. There is no 400 block and, thus, no 418. I tried Queensway1 and Kingswood. On Kingswood, I found a 418, but I could tell that this was not, of course, the house. I took a quick picture anyway. Then I left.

*

In his introduction to William Eggleston’s Guide, John Szarkowski tells his readers to take their instant cameras and “point the machine at random this way and that, quickly and without thought. When the film is developed every frame will define a subject different from any defined before. To make matters worse, some of the pictures are likely to be marginally interesting.”

This is an unusual problem, an inversion of the novelist’s or composer’s or painter’s struggle with the sheer physical effort required to make their art. You cannot press a button and produce even the worst two hundred pages of prose or a very sloppy painting or an awful symphony.

The technical ease of photography is both the cause and the outcome of the serious photographer’s other major problem: that photographs are so ubiquitous, that photographs are so often made, that photographs are so often made with a purpose: to aid our failing memories.

Anticipating this response, serious photographers often seek to take pictures that avoid their utilitarian function and exist exclusively in formal terms. Szarkowski argues that this is what distinguishes the seemingly commonplace photographs of William Eggleston: “One can say then that in [Eggleston’s] photographs form and content are indistinguishable—which is to say that the pictures mean precisely what they appear to mean.”

Meatyard, who, after all, bought his first camera so he could, like so many American parents, take pictures of his kids, has a very different way of confronting this problem. Instead of avoiding photography’s function as a memory-making and documentary device, he works from within this tradition. He populates his pictures with his family. He shoots them in houses and yards. In the case of The Family Album of Lucybelle Crater, he literally makes a photo album. He scrawls self-reflexive captions (“Lucybelle Crater and her editorial friend’s symbolic son,” for example), the kind only a family member could discern, beneath them. He tells his subjects to act naturally. He has them sit on a suburban front stoop or stand before the family car. He dresses them in whatever was on the racks of the local department store and, thus, on the hangers in their closets. He shoots in tight focus from commonplace angles with enough, but not too much, light. He shoots his wife—she is Lucybelle—with their friends and family. And then, radically recontextualizing all of this in a single move, he has them wear freakish, costume-shop masks.

By retaining, rather than dismissing and avoiding, our preconceived notions about what a photograph is, Meatyard anticipates, encourages, and ultimately frustrates our expectations of what a photograph can be. By retaining so many of vernacular photography’s characteristic elements, he proclaims that these are glimpses of fuller stories, but he does not, as an aunt showing us her photo album would, tell us what they are. And so we, looking at these unusual pictures and knowing nothing about the stories they reference, are left to discover them for ourselves.