A Threat to the Genesis Narrative of Russian Cinema

Wladyslaw Starewicz was supposed to be Russia’s earliest animator. As the story goes, the young insect-enthusiast once tried to film two male stag beetles fighting over a female, but his nocturnal actors froze, quite literally, under the bright lights of the stage. Not to be deterred, Starewicz set about working with more-pliable players, bringing his vast collection of embalmed bugs to life again, painstakingly, frame by frame. In 1912 he released his first feature film, The Beautiful Leukanida, 230 meters of pure knight’s-tale parody set in a world of beetles. Though some European viewers thought that a mad Russian scientist had trained the bugs, in fact it marked the birth of puppet stop-motion.

Early cinema history, however, is a chronological minefield. Obscure precursors and forgotten contemporaries abound, their legacies buried below the known names, who are often known now thanks to their marketing or industrial prowess, not because their films were artistically prescient, or, for that matter, the first. Take, for example, the Lumière Brothers, whose 1895 Grand Café screening has attained axiomatic status as the earliest moving-picture exhibition, yet came two months after the Skladanowsky Brothers displayed their Bioscop in Berlin. Beneath the established history lies a loaded prehistory, just waiting to be stumbled upon.

While such stumbling is not uncommon, the unknown pioneers have tended to work in the film world. Perhaps that explains why the man who stole the “first” from Starewicz’s animation claims—a diligent dancer named Alexander Viktorovich Shir-yaev—met with such hostility upon his posthumous unveiling. Shiryaev trained in a world of pirouettes and pas, orbiting a cultural elite that largely couldn’t be bothered with the newfangled cinématographe, a technological entertainment that catered to the simmering proletariat, hawking its wares at countryside fairs and in musty theaters.

More likely, though, the specter of a mysterious choreographer-cum-animator threatened the accepted narrative for Russian cinema’s genesis. In 2004, when film historian and documentarian Victor Bocharov brought Shiryaev’s works to the Archival Film Festival at the State Film Archives in the Moscow suburb Belye Stolby, angst-ridden critics recoiled. They accused Bocharov of, among other things, having fabricated the films himself, presumably as an attention-grabbing stunt.

Granted, Shiryaev’s tale, told in Bocharov’s aptly titled 2003 documentary Belated Premier, borders on implausible, even to the objective eye. In it are clips of what is supposedly Shiryaev’s work: hand-drawn sequences of people dancing and snakes slithering are set in motion, calling to mind the early experiments of Muybridge or Marey; a Norman McLaren–esque trick shot depicts humans swapping seats along a row of chairs; lifelike figurines spin en pointe across a miniature stage; and a mustachioed man smokes a pipe while dancing rings around his bewitched wife.

The mustachioed man, Shiryaev himself, had in fact created the aforementioned films between 1906 and 1909—several years before Starewicz began working on his animations, and about a year before the production of Stenka Razin, a ten-minute silent film, and (allegedly) the first native film of any kind produced in Russia. Shiryaev, however, had never displayed his films publicly. And what’s more, the films—recorded on early nitrate-coated stock prone to spontaneous combustion—had survived two world wars, a bloody civil war, Stalinist repression, and the Siege of Leningrad in stable enough condition for Bocharov to make a documentary about them, and bring them to light, nearly one hundred years after the fact.

Bocharov, it turns out, came across the cache fortuitously. While digging through the Imperial Theater archives—researching a documentary about ballet—he discovered that in 1904 Shiryaev had proposed filming the stars of the ballet. Everyone, Shiryaev said, knows about film’s existence. We should use it to preserve our art for posterity. Shiryaev offered to record the dances free of charge. But his request drew the ire of the pompous theater directorate. Film, they brusquely informed Shiryaev, was “fairground entertainment” and had no place in their hallowed halls.

Bocharov, hoping that Shiryaev had not been dissuaded, continued to search for a collection of his clandestine experiments. After several years of fruitless pursuit, he received a call: “There are certain films. Maybe this is what you’re looking for…” Daniil Saveliev, a photographer who had studied under Shiryaev, possessed exactly that: the Shiryaev trove.

Despite the compelling narrative surrounding the trove’s discovery—or possibly because of it—doubts arose after the festival screening of Bocharov’s Belated Premier. A particularly telling anecdote came from Peter Bagrov, a film historian and researcher at the Institute of Art History in St. Petersburg, who wrote, “Many sitting in the hall (myself included) had the first impression, ‘Oh, how cool!’—which very quickly gave way to the more rational, ‘Oh, how suspicious!’… Someone authoritatively spread his hands and said, ‘Well, it’s clear—this is a hoax! Really, who finds pre-revolutionary films now?’”

Preferring the Shadows

The annals of history are strewn with, as the writer Paul Collins so eloquently put it, “the forgotten ephemera of genius”—the work of people whose lives time has eroded into mere footnotes (or, if they are fortunate, obscure documentaries). Many were unlucky in their time. Others just plain did not care for fame (although they rarely rejected fortune). These are men whose mention typically meets with a cock of the head and a furrow of the brow.

Shiryaev was such a man, a prominent pedagogue whose career spanned some sixty years. A list of dancers who passed through his classroom reads like a who’s-who of classical ballet: Michel Fokine, George Balanchine, Anna Pavlova, Vaslav Nijinsky. He made a living running rehearsals for the choreographer Marius Petipa, whose work you know if you’ve ever seen The Nutcracker, Swan Lake, or Sleeping Beauty. Nonetheless, today only the most zealous balletomanes know Shiryaev’s name. Where the spotlight is the goal, Shir-yaev preferred the shadows. “I have to note,” he wrote in his memoirs, “that I have generally avoided the ‘powers of this world,’ preferring to spend my time with younger colleagues and help them raise their qualifications.”

Certainly not the stuff of multimillion-dollar biopics.

Such a film, if someone were mad enough to make it, would begin with a sweeping panorama of the Italian Riviera, shot brazenly from the platform of a banking helicopter. The camera circles, and finally descends into the rolling hills. The caption reads, “Genoa 1802.” A blend of bonjours and ciaos suggests a bustling French protectorate on the verge of annexation. There, under terra-cotta roofs and late-May rays, the clockmaker Filippo Pugni names his newborn son Cesare. The Pugni name—a derivative of the Italian pugno, meaning “fist”—denotes persistence, a trait that young Cesare inherits in spades. He orchestrates his first symphony at age seven and ultimately dies at sixty-seven as the most prolific ballet composer in history. Over the course of a fifty-year professional career, he pens such classic scores as La Esmeralda (the Hunchback of Notre Dame ballet adaptation), The Pharaoh’s Daughter, and the crown jewel of the romantic ballet, Pas de quatre. His career takes him from Italy, to France, to Britain, and finally to the canals of St. Petersburg, where the precision of the French style fuses with the grace of the Italian into the apogee of dance, the Russian ballet.

Pugni’s voluminous catalog develops alongside a consumptive passion for drink, dice, and women (though not necessarily in that order). At the time of his death, in Russia in 1870, Pugni, impoverished, leaves behind twenty-two children and three lovers, of three nationalities. Among the progeny (this one a product of Pugni’s Brit, Mary-Ann Smith) is London-born Hector, who, in his heyday, calls himself “Victor,” plays the flute in the Russian Imperial Orchestra, and fathers an illegitimate son with a budding ballerina by the name of Ekaterina Ksenofontovna Shiryaeva. Their son is our Alexander.

Flash forward to central Moscow, coronation day 1896. Alexander, now twenty-nine, has become a promising young dancer in the Mariinsky Ballet, noted for his expressiveness and lively comedic streak. We see Cossacks on steeds mingling with pilgrims and kings, passing buildings bedecked in ribbons, flags, fabrics, and swags. The Lumière Brothers, eager to capitalize on their invention’s novelty, have sent deputies across the European continent. Atop a platform in the Kremlin courtyard, a seventeen-year-old lab technician named Francis Doublier sends film rolling for the first time ever in the country that would later produce Eisenstein, Vertov, Tarkovsky, and Mikhalkov.

The streets look black from above. Writing in Harper’s, Richard Harding Davis put the spectacle in terms comprehensible to an American audience:

Imagine a city with its every street as densely crowded as was the Midway Plaisance at the Chicago Fair, and with as different races of people, and then add to that a presidential convention, with its brass bands, banners, and delegates, and send into that at a gallop not one Princess Eulanie—who succeeded in upsetting the entire United States during the short time she was in it—but several hundred Princesses Eulalie and crown-princesses and kings and governors and aides-de-camp, all of whom together fail to make any impression whatsoever on the city of Moscow, and then march seventy thousand soldiers, fully armed, into that mob, and light it with a million colored lamps, and place it under strict martial law, and you have an idea of what Moscow was like at the time of the coronation.

And as any royal knows, no coronation is complete without entertainment. In honor of the occasion, Czar Nicholas II has commissioned a splendid new ballet, which will bring together the best of the best from the Moscow and St. Petersburg theaters. Our modest hero Alexander prepares the Mariinsky troupe in St. Petersburg while Petipa rehearses in Moscow.

For some time, however, Alexander’s idée fixe has been human movement—its sources, representation, and reproduction. Though he does not lack talent, his stature makes him unfit for the long-legged male archetype, compelling him to switch to so-called “character dance.” Until his arrival, character dance—often derived from ethnic or folk steps like the Hungarian czardas, Polish mazurka, or Spanish tarantella—was not a particularly glamorous assignment; it usually appeared as a divertissement at the end of a performance, or as an interlude meant to relieve the main dancers. Consequently, it received little formal study in the ballet academy. Unsatisfied, Alexander has been working tirelessly to raise the quality of character dance.

During the early 1890s, he spent two years observing and sketching ethnic dances in the countryside of Russia, Spain, Sweden, Italy, Ukraine, and Hungary. “I collected materials from different sources, as experience taught me that sometimes you can find interesting clues where you least expect them,” he later writes. This study led him to create the first character-dance class in the history of Russian ballet. But even the most detailed drawings could not replace a visual demonstration: “Therefore, the teacher spent the entire lesson demonstrating the exercises himself; in other words, he danced—sometimes for several hours!” His class is a boon both for the students absorbing his knowledge and for Alexander himself, whose renown grows.

Meanwhile, back in Moscow, Doublier, camera in hand, has followed a peasant mob to the Khodinka field, a pothole-ridden military training ground on the northern outskirts of the city, where a public feast awaits them the next morning. For weeks, flyers have promised resplendent gifts on the day of the coronation:

every visitor to the field stalls will receive a kerchief containing sweets, gingerbread, sausage, an enamel mug, and a program of the festivities.

they will also be given a bread roll, a pound in weight.

special stalls will be set up around the edge of the field for dispensing beer and mead.

Anticipation—free beer!—drives crowds to amass long before the festivities are set to begin. As the royal family sips champagne, a fracas brews. Late night begets early morning. Rumors of shortage spread. Elbows are thrown. Legs entangle. Stampede. Doublier climbs onto his neighbor’s shoulders and scrambles across grasping hands toward his camera, toward safety. He narrowly escapes to record the carnage.

The commotion ends in a medley of mangled limbs. Official figures put the death toll at 1,389, but the psychic damage runs deeper. Some call the day “Bloody Saturday.” Authorities hold Doublier and his suspicious camera for questioning, eventually confiscating the damning footage.

Change simmers through the ensuing decade, and by December 1904, when Alexander celebrates twenty years of Mariinsky service, we find the world in flux. A strike at the Putilov artillery plant spurs growing social unrest. Cascading walkouts sweep St. Petersburg into the new year. No newspapers. No electricity. Street-side campfires illumine the city. Committees crop up in every sphere of life. Even at the ballet school, a bloc of budding young Robespierres comes together to demand higher cream-content in their milk, trying to emulate the new revolutionary spirit.

The czar’s restive forces eventually open fire on peacefully protesting workers. Again, hundreds and hundreds die while the ballet plays on. Petipa writes in his diary, “It’s too much—here they’re dancing and in the streets they’re killing.” This time they call it “Bloody Sunday.”

Inside the ballet itself, the new director of theaters, Vladimir Telyakovsky, resolves to oust the aging legend Petipa. Petipa calls Telyakovsky “my bitterest enemy.” And Alexander, now second ballet master, finds himself caught between the two. Intrigues ensue—altered productions, stripped duties, incessant bickering. At Petipa’s jubilee, Telyakovsky engages in sabotage. When the dancers present Petipa with a wreath, a moment akin to a curtain call for his career, Telyakovsky orders his lackeys to keep the curtain closed.

Petipa stops coming to work, leaving the Mariinsky troupe in Alexander’s hands. During his ever-so-brief tenure as de facto maître de ballet, the management nicknames Alexander “the Red” for his unusually democratic approach and tenderness toward his employees. Telyakovsky continually demands that Alexander alter Petipa’s classic choreography, a major affront. Ultimately forced to choose between his career and his loyalty, Alexander resigns his post in protest. He leaves having staged only one original production: a one-act ballet called At the Crossroads. The title could not be more apropos.

In keeping with the times, the dancers threaten to strike unless the theater reinstates Alexander. But their efforts are futile, and Alexander finds himself suddenly unfettered. His release from the Imperial strictures means, among other things, time and space to experiment with film. Although his bosses initially rebuffed his request to record the ballet, he goes ahead and buys a camera anyway, an early amateur model called the Ernemann Kino.

Since Doublier’s days, cinema’s popularity has exploded. Early audiences gather in the countryside, where cheap entertainment is in high demand. People had normally occupied themselves with group song and dance, and, by contrast, cinema represents, as the historian Jay Leyda puts it, “manna from a French heaven.” Production techniques are refined, and kinotheatres begin cropping up throughout Moscow and St. Petersburg. In 1908, the government, under pressure from the classical theater, caps the number of movie theaters in Moscow at seventy-five. The playwright Leonid Andreyev, himself a cinema advocate, bemoans, “Almost no other invention has been greeted with such great mistrust and even scorn as the cinematograph, or living photography. Whereas the man in the street throughout the world and the lower strata of the intelligentsia have surrendered enthusiastically and ecstatically to the power of ‘cinema,’ the upper echelons viewed it with coldness and animosity.” The earliest native producers, Drankov and Khanzhonkov (Russia’s equivalents to Pathe and Gaumont), battle for viewers’ rubles by employing themes crafted to fill halls. Foreign newsreels, melodrama, and comedy carry the day, with quality patently subservient to allure.

You can’t quite call cinema “art” during these years. In the eyes of the intelligentsia, it is more akin to a new instrument than a new creative field. The poet-revolutionary Vladimir Mayakovsky (who will later experiment with film himself) professes, “Can cinema be an independent art form? Obviously not… Art produces elevated images while cinema, like the printing press for the book, multiplies and distributes them to the most remote and distant parts of the world. It cannot become a specific art form but to smash it would be as absurd as smashing a typewriter or telescope…”

Alexander approaches film from a similar perspective, acutely aware of the camera’s potential utility within the world of ballet, and largely unaware of its independent expressive capacity. First and foremost, he attacks the thorny problem of notating movement, which ballet has wrestled with since its incubation in the Renaissance-era courts of Italy and France. The essence of performing art lies, at least in part, in transience, but unless that transience comes coupled with a system of documentation, any given performance becomes an island unto itself, moored to the world by only the wispy rope of oral tradition.

Unlike music, whose notation has not varied systemically since the monk Guido d’Arezzo invented the staff in the eleventh century, dance has cycled through eighty-five different written systems over the centuries. The earliest cropped up in France during the mid-sixteenth century, the work of Thoinot Arbeau, who instructed his readers that “if you desire to marry you must realize that a mistress is won by the good temper and grace displayed while dancing.” Some methods rely on symbolic drawings, which to the untrained eye resemble embellished crop circles. Others, like the system created by Alexander’s colleague Vladimir Stepanov, try to transpose body parts into musical notes. Most are abstruse and impractical. Alexander recalls that Petipa eschewed Stepanov’s system, “in view of the complexity of the approach and in particular of the decoding… when it came to the decoding of one line of such a record, it took [Stepanov] an hour and a half!”

Compared with written systems’ complexity and oral systems’ imprecision (imagine trying to describe a dancer’s movement so that it could be repeated, then imagine the multiplicity of verbs and adverbs you would need to add shades of meaning, then imagine describing ten dancers’ concurrent movements… well, you get the picture), a film recording seems a lucid alternative. And so, in 1906, Alexander begins shooting.

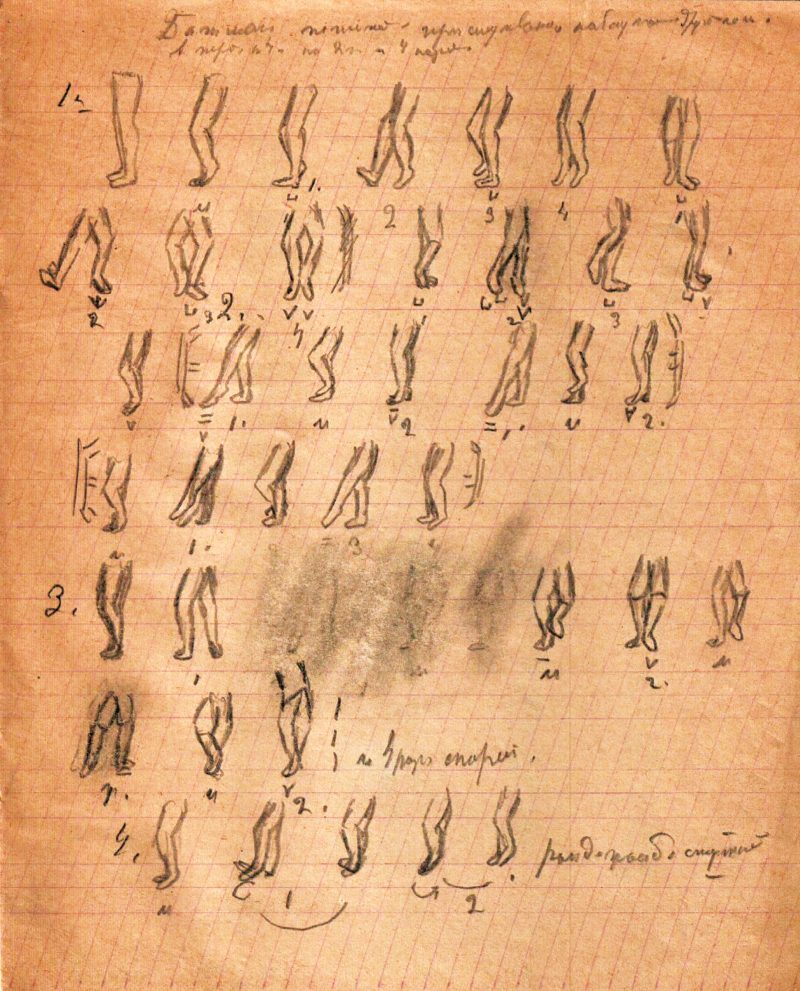

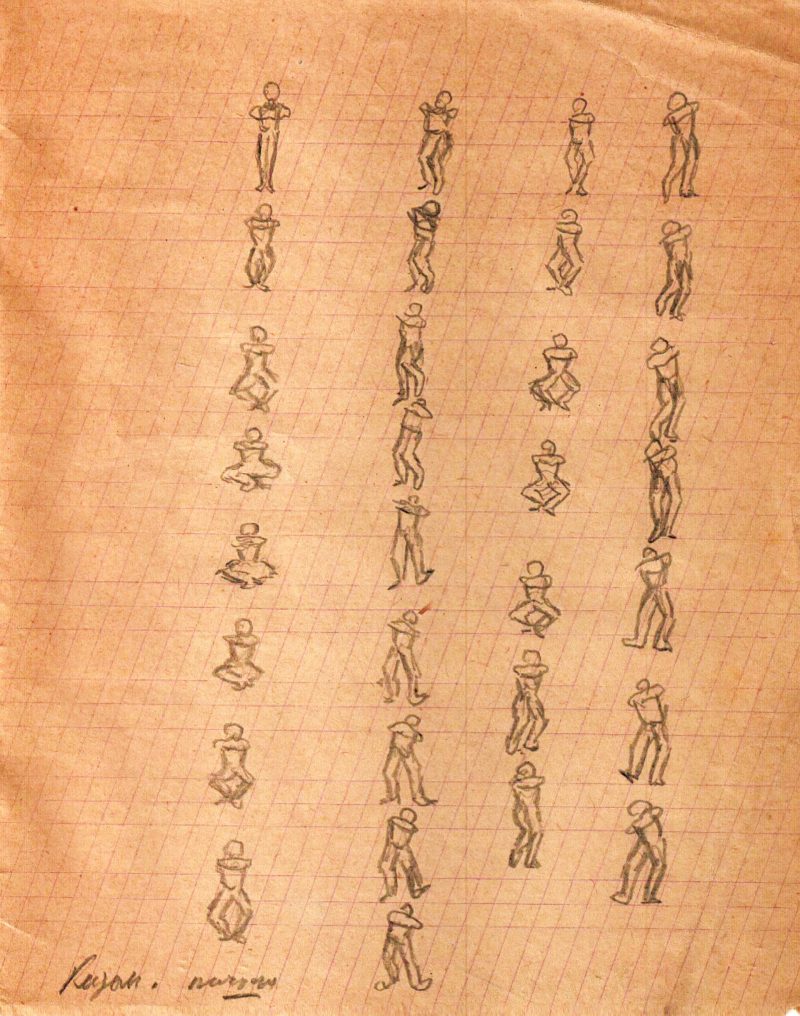

His exploration takes on many forms—trick films, family scenes, animation—but two methods in particular stand out for their dazzling ingenuity. On rolls of paper about four inches wide, Alexander sketches step-by-step progressions of motion, some stretching nearly 230 feet. Then he brings the primitive filmstrips to life using a homemade zoetrope-like device, rigged with mirrored prisms and a hand crank. Visitors to his enchanted flat can watch flocks of birds soar and dancers gyrate as the paper glides along curved tracks. Alexander especially cherishes his reproduction of the Buffoon’s Dance, a short piece that he choreographed and performed for the world premiere of The Nutcracker back in 1892. Every twist and turn, all broken down into constituent parts, flashes before the viewer’s eyes. Like Marey’s chronophotography, Alexander’s paper films are an exercise in the documentation and perception of movement through space.

This intricate technique, however, is just the beginning. Alexander reaches the zenith of his cinematographic phase when he applies his uncanny choreographic memory to puppets. He assembles twenty-five papier-mâché dolls, each around ten inches tall with malleable wire skeletons. Transitioning to three dimensions allows him to reconstitute entire productions, complete with a miniature theater and faithful stage settings. Again, he breaks down every step, no detail too small to ignore, not even the head-tilt of the most minor background character or the sway of a freshly spun spiderweb. And if the puppets alone weren’t onerous enough, Alexander occasionally incorporates drawings into the scenes as well. During a film he calls Artist Pierrot, onto the background of the stage he re-creates two characters painting a house and pouring paint onto each other, all with a fluidity that baffles the rational intellect. The longest animation, a condensed version of the ballet Les millions d’Arlequin, runs some seven thousand frames, each requiring individual conscientious adjustment. For Alexander, though, this laborious production constitutes only a continuation of his daily work at the Mariinsky over the previous twenty years.

The connection between ballet and animation appears tenuous at first glance—what does Mickey Mouse have in common with The Nutcracker?—but they are actually children of the same idea. Both arise out of drawn movements (not, as Norman McLaren points out, drawings that move). In ballet, choreography is not about people, not about an individual moving, but rather about the whole scene, about how the image of the stage and the dancers on it changes from step to step. A ballet master must compose his dance as a photographer composes a shot. And in animation, a director acts according to the same precepts.

Yuriy Norshteyn, the Soviet animator whose 1979 masterpiece Tale of Tales has been named the greatest animated film of all time on multiple occasions, depends on this relation for his work. He says, “I am always repeating that pantomime, dance, ballet—it’s all the basis of animation. Once somebody asked, ‘What qualities do you look for in evaluating animation scripts?’ It’s very simple.

I look at whether it’s possible to transfer it into a ballet or not.”

Of course, Alexander works in the opposite direction, transferring ballet into richly saturated stop-motion. His work reflects a peerless understanding of the moving body’s intricate subtleties. A former student, Mansur Kamaletdinov, describes Alexander’s puppet theater with wonder: “When I was at Alexander Victorovitch’s place, he showed me a model of the second act of Swan Lake. In absolute detail. Twenty-four little figures of the corps de ballet, four little swans, three big swans, and Odette with the prince… It all moved.”

Kamaletdinov, who arrived in St. Petersburg as a nine-year-old orphan with no knowledge of ballet, becomes like a son to Alexander. During classes, Alexander instills in him a love for dance. And through informal conversations in Alexander’s apartment, which overflows with pictures, sketches, dolls, and diagrams (leading students to call it a “museum”), Kamaletdinov learns how to live in the world of art. He spends years absorbing Alexander’s wisdom.

“Jean-Georges Noverre wrote in his letters about ballet, he wrote them as long ago as in the seventeenth century, one line that everyone should better know, but unfortunately, few do,” Kamaletdinov explains. “He writes that ballet is ‘pictures, many pictures moving.’ I would give him ten Nobel Prizes just for this line. Because he basically discovered that it’s not a person moving, but ‘pictures moving.’ That’s a whole different sensation. And this very ‘pictures moving’ was what Alexander Victorovitch showed to me.”

By the time Alexander abandons filmmaking, in 1910, his movements have literally worn a path into the wooden floor of his workspace. Thousands upon thousands of trips walking from camera to stage, moving an arm here, a leg there, and walking back again, leave a lasting imprint. Here, though, we largely lose his trail.

The months of the calendar fly by, splitting the next decade into a series of tragic snapshots: Alexander’s daughter, Alexandra, drowns; Alexander breaks his leg during a performance in London; depressed, he leaves Anna Pavlova’s European touring company; Alexander’s wife, the dancer Natalia Nikolaevna, also dies. With revolution ravaging Russia, many emigrate westward. In St. Petersburg, the theater attendants exchange their resplendent uniforms for the workers’ dirty gray coats. While creative experimentation generally proliferates under the new regime, ballet, a vestige of czarism, comes under scrutiny. During a debate over funding, Lenin opines, “It is not fitting to support with so much money such a luxurious theatre, when we lack the means for supporting the very simplest schools in the country… [Ballet] is a piece of pure помещик [pomeschik, “landowner’s”] culture, and against this no one can argue.” Given this state of affairs, no one would begrudge Alexander if he traded the stages of St. Petersburg for the cafés of Paris. By 1924, 40 percent of the Mariinsky troupe has defected.

But Alexander, ever loyal to his beloved ballet, remains in Russia. There is work to be done, dance to be saved. His activity on the stage comes to an end in 1921, when he becomes a “Merited Artist of the Republic” and celebrates thirty-five years of artistic service with a rendition of Le corsaire. This does not, however, mark the close of his creative influence. On the contrary, his legacy takes shape in large part thanks to his pedagogical work. The makeup of his pupils changes markedly. Alongside the lithe ballerinas now stand people from all walks of life, seeking their slice of the democratized ballet knowledge. “Sometimes the Red Army danced in felt boots,” Alexander recalls in his memoirs. “You could say, ‘Stretch your toe,’ and they’d answer, ‘I did, but you can’t see it in the felt boots.’”

By and by, after losing his second wife to schizophrenia, he settles into working with students from the Soviet republics. These young people, like Mansur Kamaletdinov, arrive from Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Turkmenistan, and Bashkortostan with little knowledge of ballet, or even of the Russian language. Characteristically, Alexander embraces the challenge with gusto:

I have to admit that, in the beginning, it was not easy to work with them, as they did not know Russian, and I had to show them all the dance movements myself… but they have become genuinely fond of their studies, have grown accustomed to me, and now impatiently await my lessons. They are very interested in dances, literally “devouring with their eyes”… “Who knows,” I often think, looking at these young adolescents, “perhaps a brilliant future on the stage awaits some of them.” That would be my biggest reward—and for my comrades, too.

Alexander’s swan song comes in 1937, when he practically adopts Ninel Dauytovna, a young student from the Bashkir capital of Ufa. Stalin has purged her father, the poet Dauyta Yultiya, and sent her mother to wither away in the Siberian gulag. During those years, the regime saw anyone exhibiting non-Russian nationalist sentiment as a threat, and Yultiya, active in Bashkir theater, fit the bill. At great personal risk, Alexander claims Ninel as his granddaughter, saving her from her parents’ tragic fate.

“It was he who sent the money, he did everything for me to be sent to Leningrad again. And practically took on everything for a daughter of an enemy of the people. Everything. He provided for me, he clothed and shoed me,” she says from Kazan, where she started her own choreographic school. At eighty-five, she carries Alexander’s memory with her to the classroom where she still teaches daily. “He was a genius. I have but one word for him: потрясающий [patryasaiyushii].”

Her choice of words suits the so-called “Master of Movement.” потрясающий comes from the verb потрясать (patryasat), meaning “to shake, shock or stagger”—all connoting motion. And when Alexander dies, in April of 1941, it is probably the first static moment in his long life.

Two months later, the Siege of Leningrad begins. Alexander’s “museum,” and all of the treasure in it, perishes. Not a trace remains of the man colleagues called “the finest Soviet pedagogue of the Leningrad Choreographic School,” save for his students’ memories, a portrait in the school theater, and, you may recall, a stockpile of steadily yellowing film…

The Montage that is Truth

Following the 2004 screening of Bocharov’s documentary and the uproar it precipitated, the Russian film journal Film Critic’s Notes published a one-hundred-page symposium exploring what one critic called “the loudest film sensation in many years.” The editor was a believer, and the magazine’s approach sanguine, but the critical essays were largely skeptical, with a begrudging dash of encouragement—affirming Shiryaev’s actuality, urging further study, but only following page after page of misgivings and queries. Why weren’t the films screened when they were created? How could someone work so hard for no recognition? Didn’t he want fame? Or fortune? Though the proof seemed irrefutable—the references to Shiryaev’s film studies in ballet colleagues’ writings, and the original 17.5 mm negatives—people in Russia persisted in doubting.

With time, word of Shiryaev’s work spread westward. The Lincoln Center screened Bocharov’s Belated Premier at the 2005 Dance on Camera festival, prompting the New York Times dance critic Anna Kisselgoff to gush over the “groundbreaking films.” A British Russophile, Dr. Birgit Beumers of the University of Bristol, came to Bocharov’s aid, bringing connections to restoration specialists and an impressive intellectual pedigree to bear on his findings. Their partnership culminated in a slender collection of academic studies called Alexander Shir-yaev: Master of Movement, which was published (in English) in 2009.

Back in Russia, denial gave way to disregard, a less conspicuous but equally potent form of historical erasure. Resigned to accepting the trove’s veracity, critics have responded by ignoring its creator. Serious interest in Shiryaev has yet to materialize, and Bocharov, still sitting on more than half of the original never-before-seen cache, has been unable to find funding for a follow-up documentary. “The only bright thing is that experts now know about him,” Bocharov says from St. Petersburg. “It would be entirely different, though, if they would think about it seriously, try to analyze, to find Shiryaev’s place in the general history of cinematography.”

The irony of the whole affair lies in the fact that film was merely a hobby for Shiryaev, a dalliance in the lively life of a brilliant polymath. “I don’t think that he worried about the future of his films, about someone, sometime, studying them,” Bocharov says. “If he thought that, he would have made sure that they were saved—given them to an archive or a museum—but we came across them by pure chance… It was a secondary part of his life, not the main one, which of course was his work as a dancer and pedagogue.” Shiryaev did not realize that he was an animation pioneer; he could not imagine the cinematic import of his terpsichorean exploration. What we see in his films amounts to a grainy trace of creative genius, and while we know him now on their basis, his life was richer than what the kino-eye could ever capture.

Upon viewing the Lumières’ cinematographe for the first time, Maxim Gorky wrote, “This is not life but the shadow of life and this is not movement but the soundless shadow of movement.” His words echo resonantly with respect to Shiryaev as well. What we see in his films amounts to a grainy trace of creative genius, the fleeting glimmer of a man forever in motion. We know him now on their basis, but his life extended far beyond the borders of the camera frame.

If anything, Shiryaev’s story teaches us that we are wrong to reify our historical narratives, wrong to treat history as a gapless record rather than the montage it is in truth. “The most harmful thing,” Bocharov advises, “is stasis, immobility. In art, in scholarship, in life… No one can be sure of anything. In any part of the world, there could have been enthusiasts just like Alexander Viktorovich, sitting at home, creating alone… there are many things we do not know. Many, many things…”

The author would like to thank Anastasia Smirnova, Ida Poberezovsky, and John Kolchak for their assistance with translation.